Search

Recent comments

- hit?....

48 min 54 sec ago - cooperation....

3 hours 54 min ago - leave....

21 hours 45 min ago - costly....

22 hours 37 min ago - stormtroopers....

23 hours 55 min ago - friend-ships.....

1 day 1 hour ago - the lobby....

1 day 2 hours ago - not worth...

1 day 4 hours ago - illegal stuff....

1 day 4 hours ago - no shipping.....

1 day 14 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

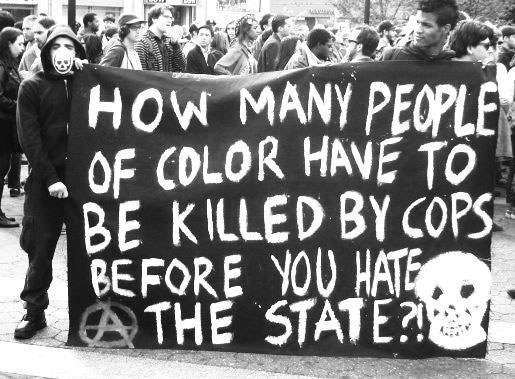

deaths in custody: death in black & white ...

Imagine if a royal commission was held into a matter of national shame and, after tens of millions of dollars was spent and a five-volume report produced, the headline indicators of that shame actually went backwards.

Consider the public reaction if, 25 years on, one of the commissioners who produced the report lamented that the situation was now worse than when the report was published, and the federal minister responsible issued a statement applauding progress.

Contemplate the level of anger, outrage and despair, especially within the community covered by the report, if deaths every bit shocking as the one that triggered the commission were still taking place.

Then consider the deeper, more disturbing truth: all of the above is accurate, yet the vast majority of Australians are only vaguely aware of the grim reality, and most of the politicians representing them seem content with things as they are.

Author Richard Frankland asks: "What would you do? Where would you put the memories? What would keep you sane? Who do you think could understand what you carry inside you?"

This was not the expectation when the report of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody was tabled in Parliament on May 9, 1991. In a powerful editorial endorsing all 339 recommendations, The Age called it "a judgment in black and white".

At the time, Ron Merkel QC, the prominent barrister and (then) president of the Victorian Council for Civil Liberties, sounded one note of caution. In a letter to this newspaper, he wrote that the inquiry delivered a "unique catalogue of the destruction of the culture, spirit and lives of Aboriginal people"; examined a wide range of policies designed to avoid the failures of the past; and proposed a "blueprint" for tackling the underlying causes of the disintegration in Aboriginal society.

What outraged Merkel was that a mere 150 copies of the report were made available for public sale (another 200 were offered in response to complaints), denying an invaluable resource to the scores of agencies, government departments and organisations that desperately needed one. (By way on contrast, 2000 copies of the report of the Victorian government's Royal Commission into Family Violence have been published, even though this is a report covering one state and is available online.)

"It is no small irony that the principal finding as to the cause of so many of the problems investigated was the failure to educate the Australian public about Aboriginal people," Merkel wrote.

So what is the story, 25 years on? According to the federal Minister for Indigenous Affairs, Nigel Scullion, many of the recommendations have been implemented and the anniversary is a time "to acknowledge the progress that has occurred to reduce Indigenous deaths in custody".

"At the time the royal commission was established in 1989, First Australians were more likely to die in custody than non-Indigenous Australians. This is no longer the case," he said.

With respect, minister, this is beside the point. The issue is whether Indigenous people are more likely to be placed in custody or prison because of their Aboriginality, with the inevitable result that lives are destroyed and lost.

On this, the royal commission was explicit: "An examination of the lives of the 99 (deaths investigated) shows that facts associated in every case with their Aboriginality played a significant, and in most cases dominant, role in their being in custody and dying in custody."

The situation now was summed up by the Chief Justice of Western Australia, Wayne Martin, who said in a speech last year: "Aboriginal people are much more likely to be questioned by police than non-Aboriginal people. When questioned, they are more likely to be arrested rather than proceeded against by summons. If they are arrested, Aboriginal people are much more likely to be remanded in custody than given bail.

"Aboriginal people are much more likely to plead guilty than go to trial, and if they go to trial, they are much more likely to be convicted. If Aboriginal people are convicted, they are much more likely to be imprisoned than non-Aboriginal people, and at the end of their term of imprisonment they are much less likely to get parole than non-Aboriginal people."

As Patrick Dodson, one of the commissioners, reported this week, the rate at which Indigenous people are imprisoned has more than doubled over the past 25 years; the incarceration of Indigenous women has risen by 74 per cent in the past 15 years; and Indigenous youths now comprise more than 50 per cent of juveniles in detention.

This is the big picture, borne out by the statistics, with one notable exception: Victoria, the only state to reach a formal Aboriginal Justice Agreement after a 1997 summit reviewed progress in implementing the commission's recommendations. Here, the parties take the agreement seriously and hold each other to account.

The small picture is revealed in two recent inquests of Aboriginal women in the west that expose failings as comprehensive as in any of the deaths investigated by the commission.

One is the case of Ms Mandijarra, who was found dead in the Broome police lock-up in November 2012 after being arrested for drinking on the local oval. The other concerned Ms Dhu, 22, who was in police cells for non-payment of fines that stemmed from offences that began when she swore at police as a 17-year-old.

A compelling case can be made that both women would be alive today if the recommendations of the royal commission had been implemented in a comprehensive manner. The same goes for Kumanjayi Langdon, who died in a Northern Territory lock-up last year after being picked up in a "paperless arrest" for drinking, and several others.

For all the claims by governments and their agencies that the commission's report as been acted on, Peter Collins, of the Aboriginal Legal Service of WA, says: "The reality outside Victoria is the recommendations dropped off the radar long ago. If you asked a police officer working in a busy regional police station in WA whether he knows about any of the recommendations, the likely answer would be 'no'."

Greens senator Rachel Siewert sees value in an inquiry into if, and how, the states and territories have implemented the commission's recommendations, but whether such a move would temper the "tough on crime" instincts of the WA and NT governments in particular is doubtful.

"It isn't ignorance of the recommendations that is the problem – it's the enduring belief that locking more and more people up is going to solve the problems of criminal offending and make the community safer, despite decades of evidence that shows the absolute opposite," says Jonathon Hunyor, principal legal officer of the North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency.

Another step forward would be to accede to the calls from groups like the Change The Record coalition and commit to justice targets and invest more early intervention, prevention and diversion strategies.

If those in power need motivation, they could do worse than put themselves in the shoes of Gunditjmara man Richard Frankland, who worked as a field officer for the royal commission, compiling the case stories of those who died in custody.

The impact is summed up by Jack, a character in Conversations With The Dead, the confronting play Frankland wrote about his experience.

"Imagine that you're a Koorie, that you're in your mid-20s, that your job is to look into the lives of the dead and the process, policy and attitude that killed them.

"Imagine seeing that much death and grief that you lose your family, and you begin to wonder at your own sanity. Imagine when the job's over but the nightmares remain and the deaths keep on happening more than ever.

"What would you do? Where would you put the memories? What would keep you sane? Who do you think could understand what you carry inside you?"

What would you do?

Michael Gordon is the political editor of The Age.

Deaths in custody: Death in black and white

- By John Richardson at 16 Apr 2016 - 2:10pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

death by police neglect...

Woman found dead in Maitland police station

UPDATE, 5.50pm:

An Aboriginal woman who died in police custody was locked up for walking home drunk, her family said as they accused police of failing to follow proper protocols.

Rebecca Maher, 36, was found dead in a cell at Maitland police station at 6am on July 19, marking the first Aboriginal death in NSW police custody since 2000.

She was picked up by police at 12.45am that morning on the side of a road in the Hunter Valley town of Cessnock after witnesses reported her wandering on the road in a heavily intoxicated state.

The mother of four, a Wiradjuri woman, was placed in a cell alone around 1am and checked on at 6am.

A cause of death hasn't been determined but Fairfax Media understands she had vomit around her mouth.

The Aboriginal Legal Service NSW/ACT has accused police of failing to follow legal protocols that require them to notify the ALS as soon as an Indigenous person is taken into custody.

It was only notified of Ms Maher's death on August 12, 24 days later.

"We're very concerned there's been a procedural failure this time, and that we were not notified of Ms Maher's detainment," ALS chief executive Gary Oliver said.

"If the [notification system] had been used by police when they detained Ms Maher, there may have been a different outcome."

read more: http://www.theherald.com.au/story/4100209/questions-raised-over-aboriginal-death-in-custody/