Search

Recent comments

- crummy....

4 hours 58 min ago - RC into A....

6 hours 51 min ago - destabilising....

7 hours 55 min ago - lowe blow....

8 hours 27 min ago - names....

9 hours 4 min ago - sad sy....

9 hours 29 min ago - terrible pollies....

9 hours 39 min ago - illegal....

10 hours 51 min ago - sinister....

13 hours 13 min ago - war council.....

22 hours 58 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

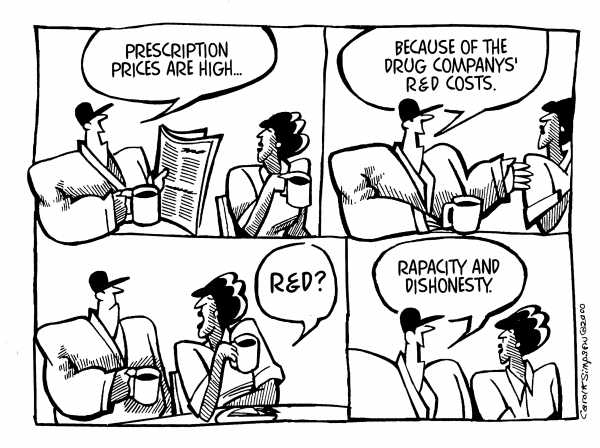

bad medicine .....

A few hours after the Supreme Court upheld his signature health care legislation last week, President Barack Obama approached a White House podium, addressed the camera and declared that the nation's top justices had reaffirmed an important guiding principle of his presidency.

"Here in America - in the wealthiest nation on Earth - no illness or accident should lead to any family's financial ruin," Obama said.

That single sentence was a compelling invocation of nearly every political theme Obama has presented on the campaign trail this year: To live in a nation is to take part in a social contract; personal wealth does not determine human dignity; decent people in a nation of means do not allow the less fortunate to suffer needlessly.

But while the president has focused on lowering health care costs at home, he has repeatedly sought to impose higher drug prices abroad. For pharmaceutical companies, that has meant steady profits, but for the global poor in desperate need of affordable drugs, those lofty prices are often a matter of life and death.

Nevertheless, members of the Obama administration continue to pursue policies around drug pricing that multiple United Nations groups, the World Health Organization, human rights lawyers and patient advocates worldwide decry.

Two weeks ago, US Patent and Trademark Office Deputy Director Teresa Stanek Rea sparked an uproar among public health experts when she testified before Congress on multiple administration strategies to affect drug pricing abroad by using American international political muscle. Her testimony focused on the Indian government's efforts earlier this year to create an affordable generic alternative to an expensive cancer drug called Nexavar, which had been patented by Bayer AG, a multinational pharmaceutical conglomerate best known in the United States for aspirin pills.

Over the course of 70 minutes, Rea repeatedly castigated India's government for approving the generic drug, calling the move an "egregious" violation of World Trade Organization treaties. India's decision, Rea said, "dismayed and surprised" her, and she boasted about "personally" engaging "various agencies of the Indian government" in efforts to overturn it.

"This is unprecedented, really shocking testimony," says Judit Rius, the U.S. manager of Doctors Without Borders Access to Medicines Campaign, an international humanitarian aid group that won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1999. "It doesn't have any ground in international legal norms. I've never really seen a U.S. government official misinforming Congress in public like this. It's embarrassing for the White House."

Thus far the Indian government has resisted American pressure and continues to offer the generic alternative, which was approved in March after several months of negotiations with Bayer.

Not once during her testimony did Rea - or any member of Congress - cite the price Bayer posted in India for its version of the drug. Bayer, which earned $3.4 billion last year, was charging over $5,000 a month for standard doses, according to data from the Indian government. The cost of a generic version: $157 a month.

It was the high price that Bayer demanded for its cancer medication that prompted the Indian government to act. In a nation with a per capita income of just $1,410, the Bayer drug is financially out of reach for most Indians. The government authorized Natco Pharma to begin selling the generic version and ordered the firm to pay Bayer a 6 percent royalty on the proceeds.

That practice, known as compulsory licensing, is commonplace. It's explicitly protected by World Trade Organization treaties, an effort to ensure that good health care is not merely a privilege for the rich - the kind of principle outlined by Obama in his celebration of the Affordable Care Act. The U.S. even deploys the compulsory licensing process to address domestic drug shortages.

But at the hearing, Rea said she planned to deploy the pressure it has used against India in other countries, too. "This is front and center," Rea said. "[We are] trying to stop the granting of further compulsory licenses."

Public health advocates have an entirely different take on the issue. They emphasize that Rea, who declined to comment for this article, did not offer a legal rationale for her agency's opposition to compulsory licensing, which goes against decades of international practices. Even the "Frequently Asked Questions" section of the WTO's website details broad leeway to approve generics that clearly apply to the Bayer cancer drug.

"Ignorance is no excuse for bad argument," says Anand Grover, United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health and Senior Advocate for the Supreme Court of India, who notes that, under WTO rules, "Setting an exorbitant price which makes the drug unavailable to those who need it ... [is] grounds for the issuance of a compulsory license."

Bayer declined to comment on specific pricing for the drug, or the Indian government's calculations, based on Bayer data, that just 2 percent of eligible patients had received the drug during its first few years on the market.

- By John Richardson at 12 Jul 2012 - 2:59pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

more bad medicine...

A private hospital which accepts NHS work has instructed its doctors to artificially delay operations on non-paying patients to encourage them to pay fees. The Department of Health last night branded the practice "unacceptable" and pledged to intervene.

Bernie Creaven, executive director of the private BMI Meriden Hospital, Coventry, had ordered an immediate four-week postponement of operations on NHS patients referred to the hospital, which will be extended to a minimum of eight weeks by September.

In a letter to the hospital's consultants dated 13 July, seen by The Independent, Ms Creaven said the imposed delays were to discourage patients thinking of going private from opting for treatment on the NHS.

Private hospitals receive taxpayer money for treating NHS cases, but can make larger fees if the patients go directly to them for treatment.

"I believe time to access the system is the most critical factor for private patients converting to NHS patients," she wrote. She added that "other aspects of differentiation" would be introduced over the next few weeks to make NHS treatment at the hospital relatively less attractive.

The Health Department condemned the move. It said NHS patients should get treatment when they needed it.

http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/health-news/private-hospital-told-doctors-to-delay-nhs-work-to-boost-profits-7962582.html