Search

Recent comments

- liberation.....

7 hours 48 min ago - killing NATO.....

13 hours 46 min ago - economic pains....

15 hours 43 min ago - in the box seat....

17 hours 11 min ago - russia excluded....

17 hours 54 min ago - be prepared....

1 day 2 hours ago - down the drain....

1 day 8 hours ago - sarkosy...

1 day 8 hours ago - workers disunited....

1 day 10 hours ago - no "brotherly" help....

1 day 12 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

more like wrestling than dancing...

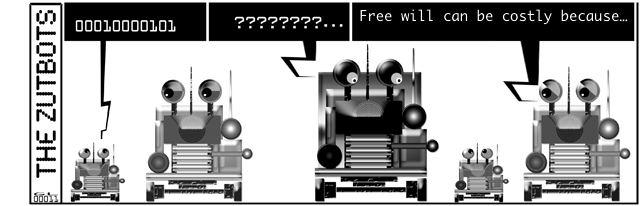

In the light of the present general lockdown without mentioning its purpose we could ask a few questions regarding “free will” and a few philosophical attitudes, when faced by interferences such as war and diseases.

Are we in the five per cent who refuse to obey orders? or can we become enraged like the people revolting in Philadelphia and now around the world? Was the death of an innocent black man, the last drop in a bucket of hidden grievances to make us flip, or are we like The Donald/Nero oblivious of the City in flame, while playing the wrong notes, including demanding that Seneca drank the Kool-Aid?

At which level of poverty — or richness — do we become opportunistic and steal some of the loot? What moral excuses will we invent in order to justify the destruction of our own house? Or the destruction of someone else's house for that matter? Or are we little bourgeois who delegate the dirty work to the meatworks and army generals?

Are circumstances determining our actions? Are our behaviour like the weather? That is to say dependant of circumstances, but we don’t have all the data to make accurate predictions beyond a certain short timeframe? Are the intensities of events predetermined as to predetermine our behaviour? Is our moral compass steady enough to make us avoid becoming the torturers and/or invaders of others?

These are questions that have plagued the top thinkers for millennium. While most of us toil without having to know, because we are told so, religion, sciences and politics have evolved mostly to protect our ability to reproduce in a variety of conflicting and conflicted systems that tried to plunder each others. In general, we are thieves in waiting, with a stop sign in from of us.

On the BBC, there is a short video three-part series about Free Will, by Melissa Hogenboom and Pierangelo Pirak.

The strange idea that we are not in control of our minds

There are many forces behind our everyday decisions. In a three part series we look at the hidden powers behind the choices we make.

—————————————

The physics that suggests we have no free will

The laws of physics suggest the future is predetermined, leading some physicists to say that it is impossible for free will to exist.

--------------------------

The surprisingly dark world of having free will

Whether we have free will or not, what’s the point of asking these questions in the first place?

Philosophers argue that there are real world implications of our understanding of free will, that force us to reflect on the societies we wish to build.

----------------------------------

And so far the quest is not new and the answers are quite unsettled and beg more questions. In the long run, what we do, free will or not, needs to have the relative purpose of providing us with pain minimisation and a level of contentment — unless we are masochists in search of pleasure or righteousness through pain…

Don’t laugh. This ability to create joy through pain is often used by leaders of soldiers and athletes. "No pain, no gain…" they say. We have already commented on this a fair while back, on this site. This was also the world of martyrs. The more you suffer, the closer to god you become.

But in these “uncertain” times, the notion of fear becomes an extended motivator, including becoming fearless looters, bypassing our already trembling moral compass because of added grievances.

For the thinker, the need to stabilise the mind and find serenity becomes urgent.

Undeniably, the society in which we are born will give us a structure in which we act. For example if Oedipus, also mentioned recently here, had not killed his father accidentally, he would never had married his own mother. But the story tends to avoid the discrepancy in the age of people, though we can accept that his mother was still of child bearing age. By the time I was born my mother was already “an old woman”. By the time I was active, she was already a wrinkled grandmother several times over.

The internet is full of sites and articles where we’re invited to gawk at 50+ old women as if still attractive in their birthday suit. But Oedipus’s fate had been planned by the gods, thus there was no escape from this. So, was the resultant of him banishing himself to expiate his actions, also part of the gods’ plans, or was it free will in self-punishment? The story is no clear about this.

Should I had been born in a poor social context would have I had similar choices to be made in my life? Unlikely…. Like born in the favelas of Rio or in the cut-throat areas of voodoo Haiti? Would I still have found happiness in fighting for my existence? The point here is not so much the choice that are on offer, but the choices that are made by others and the random encounters in the environment we’re in, versus the one we might seek.

Would the daughter of religious friends of my parents had been more attractive made a difference in my philosophical choices, including accept religious brainwashing? Thus end up like Candide with an ugly wife anyway? Or was I destined to have a good time, and question the existence of god, a question hidden from view by my upbringing, in which the only explanation, for life in paradise lost, hid all the scientific realities?

Or is our free will determined like an errant ant choosing to go this way because of the scent of other ants, leading to a food source? And is my position 275th in line to the dead worm dictating the amount I can bring back to the nest or will I choose to bring twice as much as possible, because of greed?

So be it. My destination has been to be an annoying rabid atheistic cartoonist… What has happened has happened and I cannot change this great time I already had. But can I change what comes next? Why not, if I choose to, unless the weather is crap for too many days in a row?

Take this, you democratic bastards: In countries with authoritarian governments, state-controlled media have been highlighting the chaos and violence of the US demonstrations, "in part to undermine American officials' criticism of their own nations".

In China — a country whose rulers have previously overseen the massacre of pro-democracy protesters and presently stands accused of carrying out the largest imprisonment of people on the basis of religion since the holocaust — the unrest is being used to support Beijing's repeated demands that other countries not interfere in its affairs.

Hu Xijin, the editor of the state-owned tabloid Global Times, used the unrest to condemn Washington's criticism of Beijing's crackdown on Hong Kong's anti-government protests.

"I want to ask Speaker Pelosi and Secretary Pompeo: Should Beijing support protests in the US, like you glorified rioters in Hong Kong?" Mr Hu wrote.

Fair enough. The stupid answer would be to consider that people in Hong Kong are not free to revolt while in the USA they are free to fight the police...

So in this time of isolation, it seems that many people turn to the ancients…

"Don't act like you have to live for thousands of years! The inevitable is on you suspended… ", meditated Marcus Aurelius (Antoninus) in his Thoughts, written between 170 and 180 AD, at the time of the epidemic which bears the name of his dynasty, the Antonine plague (this illness, which was smallpox, may have killed him).

Apparently, sales of the classic of ancient philosophy increased by 28% in the first quarter of 2020 compared to last year, and the Letters to Lucilius, from Seneca, are also experiencing a great boom, especially in digital format.

Author of a popular work on stoicism, A Guide to The Good Life (Oxford University Press, translated into nine languages), American philosophy professor William B. Irvine says that he has already granted half a dozen interviews on the applicability of stoicism to the current pandemic.… "For me, it's a lot”(of interviews). His visit to the podcast "The Happiness Lab" of Professor Laurie Santos, one of the stars of the psychology department at Yale University, on March 23, attracted more than 300,000 listeners.

This is what William B. Irvine has to say about the concept:

Ideally, a Stoic won’t have many negative emotions to deal with, inasmuch as he will routinely take steps to prevent them from arising in the first place. If he does find himself experiencing a negative emotion, though, he will start applying Stoic advice on how to deal with it. If he is experiencing grief, for example, he will call to mind the advice given by Seneca in his Consolations. And after doing this, he will study the episode in an attempt to prevent it from recurring.

On the other hand, a Stoic will embrace positive emotions. Because he engages in negative visualization, he will likely experience many little moments of delight in the course of an ordinary day. He will also likely have an unusual capacity for the experience of joy.

I like all the Roman Stoics, but for different reasons. When I am dealing on an ongoing basis with annoying people, I turn to Marcus Aurelius. As Roman emperor, he had lots of experience dealing with annoying people. When I have an important decision to make, I turn to Epictetus and remind my self that there are things I can control and things I can’t. When I find myself lusting for consumer goods, I turn to Musonius Rufus, who managed quite well on being banished to the desolate island of Gyaros. And when I am feeling sorry for myself, I turn to Seneca. He reminds us that no matter how bad things are, they could be much worse.

As far as favorite quotes are concerned, I have a hundred of them. The Roman Stoics are wonderfully quotable. This one comes from Marcus Aurelius: “The art of living is more like wrestling than dancing.”

But does this help us in fighting the enemy, the virus? Or do we let the “experts” fight it on our behalf while they sell (give) us the idea of confinement? Is this going to change the future?

In the BBC series, one of the participants is Emilie Caspar, PhD, who explored how coercion impacts the sense of agency in the human brain, thus revisiting the famous Milgram experiment (also used by Jeff Mosley in his series) with a totally new and ethical paradigm. Here free will is being eliminated by the coercion of “orders”. This is where the “five per cent” of those who refuse orders come from, while all the others will (virtually) kill. It is to be noted here that during WW1, quite a few soldiers did not “shoot to kill” but aimed in the air... But beyond this we need to analyse the power of the mob, the power of belonging to a mob, where orders aren’t military-like but more like “following example” of others and that we may be excluding from the mob should we refuse to loot.

So we need to make sure that at anyone time, we are as much as possible free not to be like the others, while being part of the group… Not as easy as it looks and in our present devastation, we need to know the stats. In the time of Aurelius, small pox stats were that EVERYONE could be affected.

Pasteur, the noble man whom we owe “pasteurised milk” and other stuff, observed that “cow girls” milking cows, never caught small pox, though they, from time to time, caught a very mild infection called “cow pox” from the cows themselves. Pasteur saw a link. He thus somehow found a way to “inoculate” people with cow-pox to protect them from small pox. Hence the name Vaccin in French (from "cow" — “vache" in French), now vaccine in English. That’s the story anyway.

In other culture, so to speak, the young were initiated with inflicting wounds on the chests and often sent on errands in the desert. Those who survived were deemed fit to reproduce. Those who died from the possible infections were obviously not.

The Chinese had a similar practice to vaccination in the 10 century by deliberate exposure to diseases.

When old and decrepit, like Gus, isolation is a boon… and one does not need the government decrees, as long as we have enough provisions for food and toilet paper — and tons of illusions about free will...

GL.

Free wheeling....

Note: according to William B. Irvine, is there any stoic woman? ... His use of he, his and him is a bit embarrassingly sexist, but there is no common article to singularly define "him and her" together in English (and in many other languages), apart from the plural "they"... Using "they" has been a way around the problem in most dissertations by Gus, unless chosing to be deliberately differentially sexist or genderist.

- By Gus Leonisky at 1 Jun 2020 - 11:18am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

the accidental benefits...

By 1979, we knew nearly everything we understand today about climate change―including how to stop it. Over the next decade, a handful of scientists, politicians, and strategists, led by two unlikely heroes, risked their careers in a desperate, escalating campaign to convince the world to act before it was too late. Losing Earth is their story, and ours.

The New York Times Magazine devoted an entire issue to Nathaniel Rich’s groundbreaking chronicle of that decade, which became an instant journalistic phenomenon―the subject of news coverage, editorials, and conversations all over the world. In its emphasis on the lives of the people who grappled with the great existential threat of our age, it made vivid the moral dimensions of our shared plight.

Now expanded into book form, Losing Earth tells the human story of climate change in even richer, more intimate terms. It reveals, in previously unreported detail, the birth of climate denialism and the genesis of the fossil fuel industry’s coordinated effort to thwart climate policy through misinformation propaganda and political influence. The book carries the story into the present day, wrestling with the long shadow of our past failures and asking crucial questions about how we make sense of our past, our future, and ourselves.

Like John Hersey’s Hiroshima and Jonathan Schell’s The Fate of the Earth, Losing Earth is the rarest of achievements: a riveting work of dramatic history that articulates a moral framework for understanding how we got here, and how we must go forward.

Read more:

https://www.amazon.com/Losing-Earth-History-Nathaniel-Rich/dp/0374191336

—————————————

In the face of a dire planetary prognosis, American politicians in the 1980s faced a simple question: Act now, or wait and see? These are the same options avail- able to anyone presented with an un- certain future, whether rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide, a cyst that might turn cancerous, or scattered cases of an infectious disease that could explode into a pandemic. Losing Earth focuses on the first of these, but as I read the book—under a stay-at-home order in New Jersey owing to the spread of coronavirus disease 2019— Nathaniel Rich’s frustration resonated with my own. Why, he asks, did American politicians fail to act when scientists agreed that there was a real and present danger?

In 1951, environmentalist Rachel Carson had noted that the growing season in the subarctic regions was longer, growth rings on trees were fatter, and cod were migrating farther north. “The long trend is toward a warmer earth,” she wrote.

In 1975, anthropologist Margaret Mead convened a symposium calling attention to the endangered atmosphere. Arguing that the issue would need to be addressed on a planetary scale, she called for more research, especially scientific models of the likely future that could guide action in the present.

Rich observes that by 1979, scientists had assembled the essential pieces of the climate warming puzzle. By the end of the next decade, evidence regarding the future of the planet was incontrovertible: Increased levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere were causing the planet to warm. Models warned of a litany of dangers: rising sea levels, the abandonment of coastal cities, widespread droughts, and shifting agricultural belts. These issues, Rich notes, were understood to be environmental in nature and political in impact.

———

More broadly, Rich suggests that many Americans found it difficult to appreciate the connection between actions in the present and long-term effects, the lag between cause and effect exacerbated by our species’s tolerance for self-delusion.

Rich’s description of the politicians’ inaction when presented with robust scientific evidence now feels prescient. Yet from the perspective of a world beset by the social, political, and health impacts of a novel coronavirus, I found myself searching the book for the key relations that characterize the causal space between personal choices and a cultural zeitgeist. It was not until the epilogue that Rich turned his attention to the powerful dynamics of funding in science, attempts of the fossil fuel industry to manipulate the optics of knowledge for a broader public, and the disproportionate effects of climate change according to demographics and geography.

https://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/368/6494/956.2.full.pdf

——————————————

Slowdown: The End of the Great Acceleration—and Why It’s Good for the Planet, the Economy, and Our Lives

Danny Dorling

Yale University Press, 2020. 400 pp.

Even before the pandemic brought many institutions to an abrupt stand- still, a number of indicators—from fertility rates to GDP growth—suggested that human progress has slowed

in recent decades. This week on the Science podcast, geographer Danny Dorling reveals why this might not be such a bad thing. sciencemag.org/podcasts

10.1126/science.abc6198

——————————————By 1979, we knew nearly everything we understand today about climate change―including how to stop it. Over the next decade, a handful of scientists, politicians, and strategists, led by two unlikely heroes, risked their careers in a desperate, escalating campaign to convince the world to act before it was too late. Losing Earth is their story, and ours.

The New York Times Magazine devoted an entire issue to Nathaniel Rich’s groundbreaking chronicle of that decade, which became an instant journalistic phenomenon―the subject of news coverage, editorials, and conversations all over the world. In its emphasis on the lives of the people who grappled with the great existential threat of our age, it made vivid the moral dimensions of our shared plight.

Now expanded into book form, Losing Earth tells the human story of climate change in even richer, more intimate terms. It reveals, in previously unreported detail, the birth of climate denialism and the genesis of the fossil fuel industry’s coordinated effort to thwart climate policy through misinformation propaganda and political influence. The book carries the story into the present day, wrestling with the long shadow of our past failures and asking crucial questions about how we make sense of our past, our future, and ourselves.

Like John Hersey’s Hiroshima and Jonathan Schell’s The Fate of the Earth, Losing Earth is the rarest of achievements: a riveting work of dramatic history that articulates a moral framework for understanding how we got here, and how we must go forward.

https://www.amazon.com/Losing-Earth-History-Nathaniel-Rich/dp/0374191336

—————————————,

Meanwhile at the Dancing with the Songs arena, we wrestle with our emotions with music… coming next...

warum?...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J294A-R1Cjk

Robyn - Dancing On My Own

"There's a big black sky over my town."

That line from Dancing On My Own is Robyn's love letter to the weather in her home city of Stockholm, Sweden.

It's one of her two favourite lyrics from the track, which has just turned ten years old.

It also happens to be my favourite song of all time.

That means I've spent a decade of dancing and singing to it at clubs, festivals and in friends' kitchens. It's soundtracked some of the most personal moments in my life.

Under recent lockdown, it's been viewed in another new light with an accompanying TikTok challenge from Robyn herself.

Like many other people, I love the bittersweet combination of hearing something so uplifting yet so heartbreaking.

There are so many highlights but Robyn tells me her other favourite line is: "I just wanna dance all night."

Read more:https://www.bbc.com/news/newsbeat-52817969

The song is okay and would be a contender for the Eurovision. But it’s not great shakes or it is?… 22 million views...

————————

Now, are we limiting our psyche with a song that is quite self-centred and seemingly void of other social concerns than being alone on a dance floor? We’ve all been there, haven’t we dancing to Warum… There are several songs with this title :

WARUM? (1837) OP. 12 NO.3 Fantasiestücke (Op. 12) Robert Schumann

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nhd9gV5K9L8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=59cFsQ-l9AI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KrN_p9jbsfk

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kjsfaYv_3TQ

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=42nIjlB6iTE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uvf98gvkZDI

and:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K3Qzzggn--s

150, 288,000 views

And there are love songs:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z3Cb2mqDRR0

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WpmILPAcRQo

At which level of society are we stuck in this aloneness? Is there a future in being less alone? Is this due because our choice isn’t mutually accepted? Is this predestined fate? Are we doomed to misery forever on our own?… Is there some second choice in our arsenal of Love? Are we going to dance forever?

"Dancing On My Own sometimes felt like a teenage version of me that I was happy to let go of," she says.

The song came from a break-up in her own life and she became "tired of the broken heart”.

"I went through a lot of therapy, worked on myself and healed myself.

"Now I'm back loving it. I don't feel conflicted and I love performing it and playing it live."

Lovely… People grow up… But do our societies grow up beyond their own tantrumic infantility?…. Things change… and stay the same, with new technological gizmos. Our emotions can be our inspiration.

-------------------------

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nBsl7D9i6aM

Khatia Buniatishvili plays Tchaikovsky

or

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hNfpMRSCFPE

Tchaikovsky: a composer who magnificently expressed his feelings through music. He also wrote letters to his lover:

The words are tender and passionate, describing in raw detail the powerful emotions felt by one of the world’s best-loved composers. But until now some of the letters of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, in which he tells of his sexual desires, have been hidden from the world because the objects of those desires were other men.

Now the letters have been published in English for the first time, restoring sensitive passages about the composer’s homosexuality that had been deleted by Russian censors.

In one, never before published in Russian or English, Tchaikovsky wrote of a young servant “with whom I am more in love than ever”, adding: “My God, what an angelic creature and how I long to be his slave, his plaything, his property!”

Marina Kostalevsky, editor of the new volume, said: “In our book, all texts are presented in their entirety and hence are not distorted by either prudish censorial cuts or selective cuts.” She added that, while Tchaikovsky’s homosexuality had long been accepted in the west, “it is still a subject of heated and often ugly public debate” in Russia.

“When the Russian edition of the archival documents was released in 2009,” she said, “it was not perceived by many Russians as the definitive argument in a dispute that has gone on for years about Tchaikovsky’s sexuality. Some readers have even questioned the authenticity of particular letters kept in the archive. Therefore, it can be argued that the Russian edition, despite the wealth of new information … about Tchaikovsky’s life, did not erase the old biases about his sexuality in his native country.”

In one letter the composer wrote of encountering a “youth of stunning beauty”, continuing: “After our walk, I offered him some money, which was refused. He does it for the love of art and adores men with beards.”

Russian-born Kostalevsky, who is associate professor of Russian at Bard College, in New York state, said: “This passage has not been included in either the abridged version of the letters printed in Russian editions, or in one English translation.”

Read more:https://www.theguardian.com/music/2018/jun/02/tchaikovsky-letters-saved-from-censors-reveal-secret-loves-homosexuality

The Piano Concerto No. 1

For a long time, the introduction posed an enigma to analysts and critics alike. ... The key to the link between the introduction and what follows is ... Tchaikovsky's gift of hiding motivic connections behind what appears to be a flash of melodic inspiration. The opening melody comprises the most important motivic core elements for the entire work, something that is not immediately obvious, owing to its lyric quality. However, a closer analysis shows that the themes of the three movements are subtly linked. Tchaikovsky presents his structural material in a spontaneous, lyrical manner, yet with a high degree of planning and calculation.[6]

The Piano Concerto No. 1 in B♭ minor, Op. 23, was composed by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky between November 1874 and February 1875.[1] It was revised in the summer of 1879 and again in December 1888. The first version received heavy criticism from Nikolai Rubinstein, Tchaikovsky's desired pianist. Rubinstein later repudiated his previous accusations and became a fervent champion of the work. It is one of the most popular of Tchaikovsky's compositions and among the best known of all piano concertos.[2]

When performing, do we become the slave of the composer's instruction and do we dedicate all our available energies to a predictable beautiful result?... Warum?

Read from top.

making decisions...

Is it free will or the booze talking?

Or are we prone to our own decisive problems?…

The fifth Leonisky Paradox says that “Inasmuch as the Universe is predestined by the big bang to vanish, the individual human functions within, have relative free will.” The relative elements here being the social environment itself making use of the natural conditions, and of the time between birth and death. And meteorites.

"I'm becoming daily more and more misanthropic and misogynous ... nothing worthwhile, good or useful to do ... no one to devote myself to. My situation makes me horridly sad and wretched. Even musical production has lost its attraction for me for I can't see the point or goal.”

This is how Charles-Valentin Alkan, a French-Jewish composer and virtuoso pianist expressed in 1861 his lack of creative spirit, being probably depressed, to his friend, Hiller. At the height of his fame, in the 1830s and 1840s, Alkan was as famous as his friends, Frédéric Chopin and Franz Liszt — being one of the leading pianist and composers for the piano, in Paris. We still know the other two, we have forgotten Alkan...

Alkan's aversion to socialising and publicity, appeared to be self-willed, especially after a moron got the job as head of the Conservatoire in Paris, expecting to get the job himself. Liszt commented to the Danish pianist Frits Hartvigson that "Alkan possessed the finest technique he had ever known, but preferred the life of a recluse.”

An Australian pianist, Stephanie McCallum has suggested that Alkan may have suffered from Asperger syndrome, schizophrenia or obsessive–compulsive disorder. Remember Shine… Pianist David Helfgott, driven by his father and teachers, has a breakdown. Years later he returns to the piano, to popular if not critical acclaim.

But Alkan might have been unable to find a “meaningful” relationship in a French society that was hesitating between revolution, enlightenment and pissy politics in which the nobility and the bourgeois in search of entertainment were quite ignorant of the social moires. The technical term is anomie — the condition in which society provides little moral guidance to individuals.

Anomie may evolve from conflict of belief systems and causes breakdown of social bonds between an individual and the community (both economic and general socialisation). For individuals, this can develop into an inability to integrate within normative situations of their social world, an unruly personal scenario that results in fragmentation of social identity and rejection of values.

Here as well, Alkan was Jewish and, apart from music, he set himself new goals like translating into French the new and ancient testament FROM THE ORIGINAL TEXTS… This would have baffled him as well — as we know that in order for these to make any narrative sense, there had been a lot of revisionism in the 5th century AD, and much of what we know were from manuscripts by Greek forgers.

As regards the music of his own time, Alkan was unenthusiastic, or at any rate detached and possibly mildly mad. He commented to Hiller, his best friend, that "Wagner is not a musician, he is a disease." While he admired Berlioz's talent, he did not enjoy his music. At the Petits Concerts, little more than Mendelssohn and Chopin was played, apart for Alkan's own works and occasionally some favourites such as Saint-Saëns.

Yet Alkan, now a semi-forgotten composer, was a giant at pushing the ideas within rather than tinkle with our emotions… His technique in places is trance-like, using repeats and contrasts that may seem to intentionally destroy the melodies…

Was this a choice or a predestination?… Was he the sum-total of influences or could he have guided himself in this corner of special creativity… Did he feel inferior for never having creating orchestrated works for a symphony ensemble?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EqbmoEkcFUs

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles-Valentin_Alkan

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fzzCpL_i7K8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ITmxHJhBRc

Read from top.