Search

Recent comments

- DUBAI....

41 min 45 sec ago - will bibi...?....

49 min 32 sec ago - britain too...

3 hours 30 min ago - EU protests....

4 hours 31 sec ago - "budget"....

5 hours 18 min ago - idiots...

7 hours 9 min ago - crashboom....

8 hours 32 min ago - democrats?

9 hours 27 min ago - fertilizers....

9 hours 54 min ago - hit?....

9 hours 52 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

supporting a crook makes you a crook....

Australia’s alliance with the United States is no longer reliable, and clinging to it now risks Australia’s interests and values. The case for a deliberate, staged Plan B begins with strategic autonomy – and an overdue reckoning with extended nuclear deterrence.

Beyond the ruptured alliance: an outline for Plan B

One hundred years ago – in The Sun Also Rises – Ernest Hemingway wrote that some things proceed “at first slowly, and then very fast.” This is an accurate description of the decomposition of the Western Alliance in general and Australia’s alliance relationship with the United States in particular.

Indeed, Australia, among many allies, has arrived at that fulcrum at which it is irresponsible not to acknowledge that further membership, active or passive, in the alliance with the United States would be irresponsible, an inexcusable betrayal of the country’s interests and values.

The causes are legion and have culminated inexorably in the present; once overlooked, indulged, or forgiven, they now constitute the imperative for action. They reprise, but in secular terms, Martin Luther’s 95 theses, but with a singular difference: those now understanding the historical significance of the transformation have also understood the futility of reforming the alliance with the US; it is in a state of irreparable “rupture” (the term used by Canada’s Prime Minister, Mark Carney).

The question, then, as appropriately asked by Wanning Sun in a recent article in Crikey, is, does Australia have a Plan B in case the alliance emerges as no longer reliable? The question is, of course, rhetorical. In any case, the answer is in the negative.

That said, such a plan, or plans, is not beyond the imagination or intellectual defence. They might start with the observation that, imperative though the required responses might be, many cannot be actioned immediately. Any Plan B would, therefore, need timing schedules. But these would be under the rubric of an immediately declared intention by the Australian government to terminate the alliance and all related agreements and treaties.

Such a comprehensive withdrawal would allow for a tabula rasa and would, eventually, be insisted on by the United States. It would be without prejudice to subsequent agreements which would be of global benefit.

Accordingly, this would necessarily entail delays – some measured in years – both to allow Australia to develop replacement resources tailored to its needs, and for the US to provide alternative sources for services and vacate its current holdings.

The delays, however, should not obscure the transcending element of what would be a revolutionary step in Australia’s history: a conscious decision to achieve national sovereignty to the greatest extent possible.

The qualification “greatest extent possible” is essential given that sovereignty for middle powers is never absolute. Very few in history have been truly autarkic and so must develop supply chains for critical resources which are consistent with maximum strategic autonomy. It requires one of the most difficult forms of planning – thinking in terms of a Plan C to Plan B and beyond – which is to say thinking in highly disciplined grand strategic terms.

Alliances would be proscribed but networks of complex interdependence would almost automatically be brought into being. In truth they would be essential in the trading and financial spheres, as it could well be the case, given current US behaviours which favour sanctions, tariffs, boycotts and blockades as measures short of outright war. Multilateralism would be a keystone.

Such a regime would take as its fundamental principles those which guided international law for centuries – among them the treaties constituting the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, international humanitarian law, and more recently the United Nations Charter.

To the objection that severing alliance ties with the United States would prejudice Australia’s defence procurement of state-of-the-art weapons and other technology, the answer must first challenge the assumption that the record of the US system to date is in any way exemplary. Word limit constraints determine that record cannot be adduced here but the attentive readership of this website will be aware that it is far from a process to be imitated and more valuable if seen as a warning.

It should also be noted that, if the alliance is terminated then so, too, are the requirements for both interoperability and interchangeability. This argument only gathers more force in the knowledge that, so frequently, the need for US equipment and other claimed benefits is predicated on joining the US against its choice of challengers, adversaries, enemies, and illegal wars of choice.

Remove these factors from the calculations and two consequences are highly likely to follow. The first is that Australia’s defence problematic changes, and radically at that. Second, it could very well be the case that equipment from Europe and Asia might not only suffice but prove to be superior when applied to that problematic. In some cases, even now, such arrangements are in train.

These measures, important as they are, reside at the relatively mundane level of required responses. At the higher level is the need to repudiate an obscene feature which, outrageously and unaccountably, has not even been referred to throughout the national conversations, dialogues, and screaming matches on hate speech.

Extended Nuclear Deterrence – the so-called ultimate guarantee of Australia’s security – as I have written before, when reduced to its fundamentals, is nothing more than a global mutual suicide pact to ensure a stable strategic balance. The truism amongst those familiar with its Alice-in-Wonderland logic is chilling: if it fails once, it fails for all time.

While we rightfully are outraged at mass killings, argue over genocides, and who can say what about whom, the term “deterrence” is given a free pass through all national ethical and moral checkpoints as though, somehow, it does not refer to an act of almost unspeakable criminal pathology that demands rejection. Central to the Australian response would be the long overdue obligation to do so now.

What are the prospects? To ask the question differently, what is required? In one word: courage.

Courage must imbue the government. It must shed itself of decades of manicured histories and managed memories. It must task its policy planners and sundry advisers with this question: how does Australia achieve the termination of the alliance with the US and its sundry and numerous arrangements? It wants a plan to achieve it, not a narrative of roadblocks it can get from those who Paul Keating describes as the Austral-Americans.

A legitimate inclusion in such a plan would be that it will be expensive. That should be conceded from the start by government. But then the government could explain that the achievement of Australia’s sovereignty, and a reckoning with its suppressed relationship to global suicide, is long overdue.

It need not be a dismal encounter. Australia can make its own future and it will do so in the face of the systemic changes in global politics and it will be a choice between subordination and a newly discovered sovereignty.

The latter might be a lonely experience: Hans Morgenthau, the godfather of modern international relations realism, reminds us that whatever decisions we make together, we will do so “under an empty sky from which the gods have departed.”

Overall, however, the present and the future can be understood as a time of creation, and we might be guided by history – that we are more readily betrayed by our certainties than by our doubts and curiosities.

If what Australia seeks is the creation of its own unique collective identity, then perhaps a start can be made in the spirit of James Joyce – suitably modified where needed – who wrote: “Welcome, O life! I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.”

https://johnmenadue.com/post/2026/01/beyond-the-ruptured-alliance-an-outline-for-plan-b/

===================

SEE ALSO: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x62Qyhr5frg

How the U.S. Reputation is Changing Round the World /Larry Johnson & Lt Col Daniel Davis

Larry Johnson argues that in early January Iran uncovered and shut down a covert Western communications network, including Starlink terminals—contrary to Western assumptions—possibly with Russian and Chinese electronic warfare help. They reject Western narratives claiming widespread Iranian popular revolt or extreme repression, calling it propaganda meant to justify regime change and ignore decades of U.S. provocation since 1979.

They warn that imminent U.S. or Israeli strikes on Iran would trigger severe retaliation: closure of the Strait of Hormuz and attacks on U.S. bases across the Gulf. The speaker doubts U.S. missile defense capabilities, citing past failures to protect Israel, and criticizes U.S. military planners for overestimating air power while ignoring historical lessons that air campaigns alone cannot achieve political control.

More broadly, the discussion condemns U.S. foreign policy as imperial, hypocritical, and cloaked in the language of “freedom” while violating international law and causing mass civilian harm. The U.S. is portrayed as the world’s leading aggressor, with far more global bases than Russia or China combined. The speaker argues this behavior is increasingly alienating allies, noting shifts by countries like Canada and signs Europe may turn back toward Russia and China as more stable partners. They conclude that U.S. isolation is not just possible but already underway.

====================

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

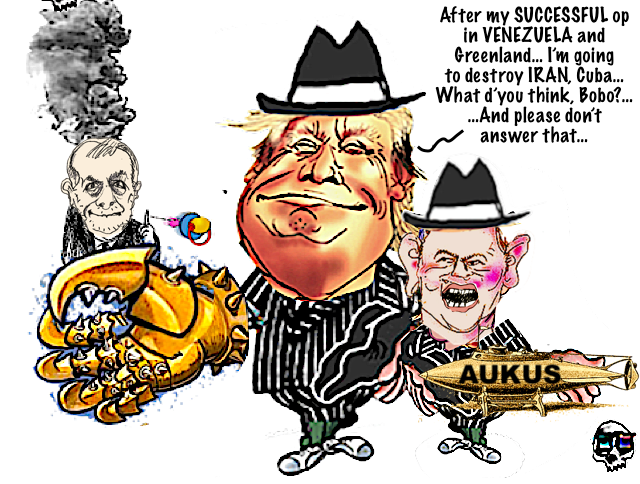

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

- By Gus Leonisky at 26 Jan 2026 - 6:50am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

cartoonists?.....

In 1949, Friedrich Hayek wrote an important article that detailed the strategy his followers could use to win the battle of ideas for the "new" liberalism he wanted to promote.

It was titled The Intellectuals and Socialism.

It discussed an idea that would inspire his friends and followers to create hundreds of free-market "think tanks" in the future to pump out new liberal ideas.

It drew attention to the unique role that "intellectuals" play in Western democratic societies.

Hayek's definition of intellectuals referred to journalists, publicists, radio commentators, fiction writers, cartoonists, artists and university lecturers, among others.

He said intellectuals had to be targeted.

He said they were a special class of people because they distilled the ideas of experts for lay audiences and performed a vital "censorship function" as intellectual gatekeepers, while influencing public opinion daily:

"There is little that the ordinary man of today learns about events or ideas except through the medium of this class," he wrote.

"It is the intellectuals in this sense who decide what views and opinions are to reach us, which facts are important enough to be told to us, and in what form and from what angle they are to be presented."

He said any attempt to revitalise liberalism would have to win over Western intellectuals.

And to do that, he said, they'd have to be presented with a utopian vision of the future that excited them:

"We must be able to offer a new liberal program which appeals to the imagination," he wrote.

"We must make the building of a free society once more an intellectual adventure, a deed of courage. What we lack is a liberal Utopia, a program which seems neither a mere defence of things as they are nor a diluted kind of socialism, but a truly liberal radicalism."

And two years after that, in 1951, Milton Friedman wrote another article along similar lines.

It was titled, Neo-Liberalism and its Prospects.

Friedman said the rejuvenation of liberalism would probably take many years. And to be successful, liberals would have to influence the climate of opinion slowly over time:

"Men legislate on the basis of the philosophy they imbibed in their youth, so some twenty years or more may elapse between a change in the underlying current of opinion and the resultant alteration in public policy," he argued.

"The stage is set for the growth of a new current of opinion to replace the old, to provide the philosophy that will guide the legislators of the next generation even though it can hardly affect those of this one […]

"Neo-liberalism offers a real hope of a better future."

According to Daniel Stedman Jones, in Masters of the Universe: Hayek, Friedman and the Birth of Neoliberal Politics (2012), it was obvious what Hayek meant in his 1949 article:

"The strategy was clear: neoliberal thinkers needed to target the wider intelligentsia, journalists, experts, politicians, and policymakers.

"This was done through a transatlantic network of sympathetic business funders and ideological entrepreneurs who ran think tanks, and through the popularisation of neoliberal ideas by journalists and politicians."

What are think tanks?This is where "think tanks" come in.

A think tank is an organisation that tries to influence public policy debates. And it tries to shape the "climate of opinion" by circulating its ideas widely and repeating its messages over and over, year after year.

Think tanks take seriously Hayek's argument that political change occurs downstream from "intellectuals".

READ MORE:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2026-01-26/atlas-network-mont-pelerin-society-neoliberal-think-tanks/105700628

======================

Are We Still in Neoliberalism?

INTERVIEW WITH

VIVEK CHIBBER

Vivek Chibber on why Trump II signals the end of an era — but not capital’s unchecked rule over our society.

The past fifty years have been the era of unchallenged market dominance in all areas of life. But with the global upheaval brought on by Donald Trump’s trade war, are we seeing the neoliberal order unraveling?

In this episode of the Jacobin Radio podcast Confronting Capitalism, Melissa Naschek sat down with Catalyst editor Vivek Chibber to talk about Trump’s tariffs, the rise of right-wing populism, and whether or not the neoliberal era has truly ended.

Confronting Capitalism with Vivek Chibber is produced by Catalyst: A Journal of Theory and Strategy and published by Jacobin. You can listen to the full episode here. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

-----------------------

MELISSA NASCHEKSo Vivek, we’re far enough into Trump’s presidency now that we have a good sense of what his agenda actually is. Did you ever picture it looking like this?

VIVEK CHIBBERI didn’t think he would change that much from his first presidency, from his first administration. So I kind of knew what kind of policies he’d pursue. But the chaos of it and the aggressiveness and the kind of mania that he brings with it — I don’t think anybody expected it to be at this level. So it’s a combination of, yeah, he’s doing what we expected. But he’s doing it so much more aggressively and single-mindedly now that it’s really shaken up the political economy and the culture.

MELISSA NASCHEKIf you look at Trump supporters, there is a portion of his base that couldn’t be more pleased, probably because they were not necessarily expecting him to go to the lengths he has. And then he did. Then another portion that was sort of betting the whole time that his presidency was going to be basically a carbon copy of his first term. And so are kind of pissed off at him that he’s actually doing all this stuff.

VIVEK CHIBBERWithin his base there’s a call to upend the system, to tear things down, to smash the institutions. And this time he came prepared to do it. And if that’s what you wanted to see, yeah, you have to be happy with it if you’re a Trump supporter.

MELISSA NASCHEKI think that’s right, if you really believed in taking him at his word. But I think a lot of people didn’t, and what’s interesting this time around is not only the intensity of his agenda and his policies, but also the lengths to which he’s going have made some people start to question: Is this some sort of turning point within not just American political history, but in the entire global economic system — specifically this idea that perhaps Trump’s new agenda signifies some end of neoliberalism?

VIVEK CHIBBERI would say there’s a turning point in many ways. Many people now believe that. You get this feeling that there’s no going back to the Bush-Obama-era capitalism, that there has been a shift in the political culture but also in the kinds of policy packages that we can expect to see now.

So I believe there’s been a shift on the issue of neoliberalism. It’s a little murkier, so let’s try to get into that a bit.

MELISSA NASCHEKYeah. So with that in mind, do you think Trump is actually the end of neoliberalism?

VIVEK CHIBBERI don’t know if Trump is the end of neoliberalism. I do believe we are in a phase of capitalism — or I guess people are calling it now late-stage capitalism. I’m not really sure what it means.

MELISSA NASCHEKAt a certain point we’re going to run out of later stages.

VIVEK CHIBBERIn the ’80s there was this term called “late capitalism”; Ernest Mandel wrote a book in the ’70s called Late Capitalism. Somehow it morphed into “late-stage,” and it makes it sound like it’s about to die or something, that it’s in its final stages and we’re just watching it slowly curl up into a ball.

MELISSA NASCHEKIt’s metastasized capitalism.

VIVEK CHIBBERWe are at something of a watershed in our political economy. And neoliberalism, as a word, is used to describe all these various dimensions of the political economy — the global dimension, the domestic dimension. Its political components, its economic policies, the labor relations, all these things come under the rubric of neoliberalism, and it starts to become something that is so encompassing that it doesn’t have a lot of analytical traction.

I think we’re seeing some important shifts in it now. So at the rock bottom, what people mean by “neoliberalism” is just a turning away from the kind of distributive regulatory regime in the ’50s ’60s and ’70s, which also had a place for labor in it.

MELISSA NASCHEKAlso known as the postwar economy and the so-called “golden age of capital.”

VIVEK CHIBBERYeah, the golden age of capital. So broadly speaking, social, democratic capitalism — turning away from that toward a more unregulated, market-based economic distributed regime. It’s called neoliberalism because it’s a new form of liberalism.

So what is neoliberalism? What they mean by that is not political liberalism, the liberalism of rights and of strong political inclusion. But what they mean is an unregulated economy of the kind you had in the nineteenth century. So neoliberalism means a new version of the nineteenth-century capitalism, which gave rise to all those gigantic social movements, which gave us the welfare state. So neoliberalism is supposed to mean, broadly speaking, a turn toward marketized forms of exchange and distribution without the heavy hand of the state intervening either in market transactions or in income distribution.

If that’s what we mean by neoliberalism, and we’re asking, “Is this the end of it?” The answer is no. Why the answer is no is interesting. There’s a partial way in which something has come to an end, and that’s what people are pointing to when they ask, “Could neoliberalism be ending?” The first is the social support for all these policies; the second is the global dimensions of those policies.

Neoliberalism Has Lost Social Support — but Capital Still RulesMELISSA NASCHEKSo what do you mean by the social support of neoliberalism?

VIVEK CHIBBERPerry Anderson wrote this article in 2000 when the New Left Review relaunched. He was relaunching it because he thought that we are in what could be a very, very long era of capital’s dominance, perhaps called neoliberalism. The idea was that this would require an entirely new intellectual agenda to make sense of it.

And at that moment, in that article, Anderson made this observation that the ideology of neoliberalism — the ideology that celebrates markets, celebrates individualism, celebrates a very minimalist state — is so hegemonic. He compared it to, in the early modern era and Middle Ages, the power of the Christian church. So Anderson thought that neoliberal ideology was extremely powerful. What that suggested at that time was that neoliberalism was successful as a political program, in part because it had garnered the support of the population through this ideology.

So when we talk about the social supports of neoliberalism, what it conveys is the sense that there was not only a consensus within the ruling classes and the political establishment for a kind of marketized political economy, but that it had also won the consent of the masses through a variety of means.

And now that support has collapsed. How has it collapsed? Well, starting at around the time of Occupy Wall Street, what had been made clear was that the enormous inequalities that had grown in the era of the 1980s and 1990s and early 2000s, those inequalities had become so stark that there was a general cultural revulsion against it, and a general sense that people should not only have political rights but also economic rights.

Now that goes against the neoliberal ethos, which says, “Your only rights are political rights in the economy.” You get what the market gives you. That’s the ideology of neoliberalism. Now, my view is I don’t think there was ever a great deal of social support for neoliberalism. I think people always hated it. I think people hated having to fend for a job, constantly having to struggle for their wages. I think they hated the insecurity that came with it, the rolling back of the welfare state.

So what changed starting in 2010 wasn’t that the support for neoliberalism fell apart. It was that the anger against neoliberalism finally came together. And in my opinion, leftists and critical theorists in the 1990s and the early 2000s who were trying to have this Gramscian theory of how consent is generated in capitalism, and how neoliberalism and Thatcherism generated consent, they were completely off-base.

MELISSA NASCHEKSo one question I have for you about that it’s not as though there has been no political resistance up to this point. Throughout this era, there’s been consistent attempts, especially by the Republicans, to basically threaten to roll back these benefits, in particular Social Security. And whenever that happens, for example, there’s always a big push of nonprofit groups and groups of elderly Americans to go to town halls to tell Republicans, “Don’t you dare touch my benefits,” and to then vote against them in the midterms as a sort of punishment.

How is this sort of political tension now distinct from those previous battles to, for example, protect the welfare state from rollbacks — something that would’ve been in line with neoliberalism?

VIVEK CHIBBERThere haven’t been any big social mobilizations since the 1980s, whether in support of Social Security or anything else. The resistance to unwinding it has almost entirely been electoral and lobbying. The lack of success on the part of the Republicans and the Democrats in shrinking the American welfare state is not because the electorate or working people banded together and launched massive campaigns and rolled back their agenda. It was because every time they tried to do it, they lost in the elections. They lost in midterms, and this is what we’re seeing right now in the fight about Medicaid in Trump’s tax agenda.

So what changed starting in 2010 wasn’t that the support for neoliberalism fell apart. It was that the anger against neoliberalism finally came together.Now that’s a different kind of resistance. That’s a resistance to unwinding certain policies. There’s a different kind of resistance to capitalism that has a positive agenda, which is not only just throwing sand in the wheels of liberalizers, it’s actually gaining some new rights within capitalism that you didn’t have before. That’s what the New Deal had done. My view is that it’s inaccurate to say that the support for neoliberalism has collapsed. It’s more accurate to say that thetolerance for neoliberalism has collapsed.

There was never a mass view of working and ordinary people that Thatcherism and Reaganism are good things. There was a grudging acceptance at best, but mostly there was a sense of resignation to it.

MELISSA NASCHEKI think that goes well with your comments about the distinction between social movements and electoral behavior, because of the commonly cited example of “actually, this was a popular decision that was made to have something resembling neoliberalism.” I don’t know that people exactly vote for that, but the working-class vote for [Ronald] Reagan is a big cited example of, “Oh, well this is what people wanted.” They actively assented to this.

VIVEK CHIBBERNo, there was no assent to Reagan’s economic program. There was no assent to what came to be known as Reaganism. There was a revolt against the Democrats. There was a revolt against the Volcker shock, the massive increases in interest rates, the unemployment that it generated, but there was never a sense that what we want to have is a rolling back of our economic rights and the rolling back of the welfare state. That’s a talking point of certain liberal intellectuals on the Right, but it’s profoundly mistaken.

I think the accurate way of describing what’s changed is that the public is no longer willing to tolerate what it was fed for thirty years, and that’s neoliberalism. There’s an anger within the culture and a demand for some kind of shift, some kind of change, which is different from what we saw in the 1990s and the 2000s.

So while it’s a mistake to describe it as a collapse in the support for neoliberalism, that description does get at something, which is that political elites cannot take for granted that they can just get away with the marketized social policies that they had implemented the last thirty years. They know that now.

That’s an important change. Because there’s a churning within the political culture in which it’s understood that political elites are going to have to, in some dramatic way, change the way they’ve been going about doing their business.

Does that mean that they’re going to move away from the Reaganism, the Thatcherism, what we know as neoliberalism? The answer to that is largely no. There’s one component of it that they are changing — that’s what we call “globalization.” I would say, however, that the end of globalization, if we want to call it that, is not the end of neoliberalism. It is simply a change within one dimension of neoliberalism.

Neoliberalism had two dimensions. There was the domestic front and there was the international front. The international front was one that tended to things like trade exchange rates, things like that. That is undergoing an important change, no doubt about that. But in terms of how states and the capitalist class deals with the domestic economy — how it accumulates capital, how it makes its profits, how it deals with labor and the welfare state — there’s zero indication that that’s going to change.

MELISSA NASCHEKCan you talk a little bit more about your second point about the base of neoliberalism, specifically the political base of neoliberalism?

VIVEK CHIBBERSo once we understand that neoliberalism was not brought about because the masses demanded it, the question is, how did it come about? Well, it came about because in the United States, and we can just stick to the United States, it was a shift within the American political and economic establishment’s understanding of how to revive growth and revive profits.

Starting in the late ’60s all the way through the ’70s, the American economy had been pretty stagnant. The consensus by the late ’70s — especially in the business community — was that the way to revive growth is, first of all, to revive profitability. Corporate profits.

Corporate profits were being dragged down, they said, because of all the excess costs that the welfare state and the trade unions had imposed upon it. The welfare state with its high levels of taxation on the rich with its great deal of social insurance, which they thought created a disincentive for workers to work.

And then, of course, the trade unions with all the demands they made on corporate revenues for higher wages, for pensions, for benefits, things like that. So the idea was that we need to regain the initiative — “we” being the business community — so that by pushing back against all these costs, we can recoup more of our revenues and keep them as profits.

It’s inaccurate to say that the support for neoliberalism has collapsed. It’s more accurate to say that the tolerance for neoliberalism has collapsed.And once we have those as profits, we can reinvest them and that reinvestment will lead to higher levels of growth. Now, this was an elite perspective. In order to pursue that perspective, they had to deal with the fact that trade unions would be opposed to it. The first item on their agenda was weakening or even getting rid of the trade unions.

So in the ’70s, what we see is a wholesale assault on the trade union movement, and it’s done for two reasons. It’s an end in itself — you get to scale back the power of the unions, and through that you increase your own power in the workplace as a manager. You increase your profits because there are fewer demands that unions can make of you.

But there’s the political benefit too, which is once the unions are gone, the main source of support for the welfare state is gone. And now you can start pushing back against all the costs that the welfare state is imposing upon you as well.

That was the essence of it. That was not brought into office through some sort of mass working-class desire for neoliberalism. It was imposed on them. And once it’s imposed on them, well, they wanted to fight back. But if you don’t have trade unions, if all your social institutions are being dismantled, how are you going to fight back? There’s nothing left. All you have left is the elections.

So once all they had left was their vote, it actually made the job very easy for the political parties because for those four years, in between the elections, you’ve kind of got a free hand to do whatever you want because the trade unions aren’t there and the social institutions aren’t there.

That consensus within the ruling class for this new kind of market economy has more or less been in place for upward of forty years now.

What Makes Trump II DifferentMELISSA NASCHEKSo what you’re laying out is that over the course of neoliberalism, there’s been a consensus that corporate profitability is being harmed by the welfare state. And that, in turn, if we want to enhance that profitability, we have to remove a major obstacle to reforming the welfare state, which is the labor unions.

Is Trump, in some way, challenging that entire consensus, because he’s somebody who ran basically both elections on “Let’s keep the welfare state untouched. I’m not going to do anything to take away your benefits”? And even if he was not explicitly pro-union in the way a Bernie Sanders was, he was not campaigning on an anti-union agenda at all.

In fact, in his first term, he was working with labor unions to keep their jobs here. And in the beginning of his second administration, a lot of hubbub was made about the fact that he was appointing a labor secretary that was for the Pro Act. So is Trump or other politicians like him, such as Josh Hawley, somehow something different?

VIVEK CHIBBERThis is a good question, and it should be dealt with at two different levels. The first level is: Could these politicians be harbingers of a kind of an elite skepticism toward neoliberalism? Again, by neoliberalism we mean the unfettered rule of markets over our social institutions. And the second level is: Even if they are skeptical toward that, are they skeptical toward the underlying issue, which is the prioritization of corporate profits and managerial power over the interests and the lives of the rest of the population?

I think that distinction is often lost in these conversations. So let’s just start with the first question. Is it possible that people like Trump, people like Hawley, are skeptical about traditional free-market rule? I think the answer to that is: yeah, they’re skeptical in the sense that they are willing to move away from some components of it in the interests of the larger class project to which they’re committed. Now, that larger class project is what I’ll deal with in the second dimension that I talked about, but the very fact that they’re interested at all in questioning it should not be elided or minimized. I think it’s a big deal and it’s resonated with the population.

The reason it’s resonated with the population is because, as I said earlier, they’re very angry. They are now no longer willing to tolerate the traditional regime. The dilemma that the American ruling class — and the European ruling class — faces is that they are not the ones who want to move away from forty years of neoliberalism. It’s being kind of thrust upon them by the population.

Populism at one time meant massive attacks on elite power. Today’s populism simply means slowing down the attacks on the working class.So what they’re trying to figure out is: How can we maintain the broader aspects of our power over the population while reengineering the institutions in some way to absorb all of the attacks and the criticism and the resentment of the electorate? That’s what they’re trying to do. Now, toward that, you can get someone like Hawley coming around and saying, “We need to preserve the social safety net.” You can get someone like Trump saying, “I won’t touch Medicaid and Medicare.”

But understand what those things are. They are not, in any way, a revitalization of the welfare state. At the very best they’re saying we will keep it status quo ante. Status quo ante is what’s caused all the anger among the population in the first place. So it is not much of a solution. All they’re saying is, we won’t keep with the accelerated pace at which we’ve been dismantling everything and forcing markets down people’s throats.

But from the people’s standpoint, it’s not nothing. It’s something, right? And they’re so desperate right now for some kind of relief from forty years of misery that a large section of the electorate sees that as something it can hold onto. So it is quite possible that you’ll find elements of the Republican Party — and in Europe, elements of the Right even — coming around some kind of support for a weak redistributive program. And by that we mean some kind of weak welfare state. That’s entirely possible.

MELISSA NASCHEKWhat they’re doing is just not continuing to attack.

VIVEK CHIBBERThat’s right. We should understand that as slowing down the pace of the dismantling rather than reversing the dismantling.

MELISSA NASCHEKRight. And it’s notable that Trump’s not getting compared to FDR here.

VIVEK CHIBBERNo. And you know, populism at one time meant massive attacks on elite power. Today’s populism simply means slowing down the attacks on the working class. That’s all it means. Okay. But look, it’s not insignificant. Even Hawley — people point to him as a harbinger of changes within the Republican Party, but he’s pretty isolated. It’s a very small contingent within the Republican Party now that is interested in preserving the social safety net. There are literally about a dozen, maybe eighteen congressmen and one senator. So we’re not talking about a major change in the party.

But again, we shouldn’t ignore it. It’s not insignificant. And if it weren’t for them right now, you would see in Trump’s tax bill a wholesale attack on Medicaid. Now there’s a deeper issue, which is suppose that version of the Republican Party, that wing of the Republican Party, that wing of the European right, does grow to some extent. And we do see a turn toward trade unions and we do see a turn toward some kind of move away from free trade and things like that. Does that mean an end to the last forty years of class dominance and employer power? The answer to that has to be no.

This means, in my opinion, neoliberalism is not the issue. Remember, we started by saying the essence of neoliberalism is a turn to the kind of nineteenth-century rule of markets. The point is that what a fully fledged democracy requires is not so much a scaling back of markets in and of itself, but the full participation of ordinary people in the political institutions that rule over them. It is possible that you can have an unfettered rule of capital in a situation where you have corporatist institutions.

MELISSA NASCHEKCan you explain what a corporatist institution is and why that would be consistent with capitalist power?

VIVEK CHIBBERWhat we’re trying to understand is: What do working people need in order to pursue their interests in a situation where their interests are not aligned with the interests of the wealthy?

The reason working-class people fought for democracy is that they thought democratic institutions, the right to vote, would be one more arrow in their quiver to try to fight for decent lives in a situation where they don’t have much control over the key institutions of society: the workplace, the government, things like that.

So they thought the vote is one very important element of that — trade unions are a very important element of that. Now, the desire on the part of the ruling class to roll back all these institutions, like trade unions and the other social institutions, was that they wanted to exercise unilateral dominance over politics and over economics.

There are several ways in which they can exercise unilateral dominance. One way is through free markets, but they can also do it by organizing civil society into what’s called corporate bodies. It’s not corporations. It means collective entities that organize people’s interests in some way. Trade unions are a corporate body. Civic associations are a corporate body. Political parties can also be a corporate body.

It is often forgotten that in the 1920s and 1930s — when the far right held the most power that we’ve seen the last century — it didn’t do it through free markets. It did it through what’s called corporatist institutions. That meant they were trade unions. They were civic associations. They were citizens’ groups. All of these things that we associate with a thriving democracy can also be instruments of capitalist power. The classic instance of this was fascism.

In fascism, it wasn’t the rule of free markets. It was the rule of corporations through things like civic associations, citizens’ bodies. They even took control of the trade unions. The reason I make this point is that what the Left ought to be fighting for is not an end to free markets per se, although that’s important. It should be the end of corporate hegemony over society. That hegemony of the employer class can be exercised through free markets, but it can also be exercised through things like company unions. It can be exercised through things like right-wing neighborhood groups whose actual function is to watch over the citizens. It can be exercised through a media that, on the face of it, is a free media, but in fact is thoroughly captured by their private owners who use it as instruments of propaganda.

That means that when we see the Republican Party moving formally toward supporting such things like some form of trade unions or social institutions — don’t take that as a victory for the Left. Because, in the context of employer and corporations’ hegemony over politics, these overtures toward unions, et cetera, can be turned toward employer interests and not toward workers interests.

So right now, when we see someone like Trump or Hawley saying we should move away from neoliberalism, that doesn’t mean that they’re saying we should move toward worker empowerment. They could simply be saying we need new forms of social control. And those new forms of social control formally, on the surface, can actually look like the kinds of institutions that we associate with a thriving democracy. Historically, the polar opposite of a democratic society, which is fascism, had all sorts of institutions that were anti–free trade, anti–free market, none of which went toward labor’s interests.

The Beginning of De-Globalization Is Not the End of NeoliberalismMELISSA NASCHEKI think your comments lend a lot of clarity on the state of the political situation. But probably the biggest phenomenon that people point to when they say “this means neoliberalism is ending” is the attacks on globalization and the supposed deglobalization that Trump is instituting. How legitimate do you think that is? Are we deglobalizing?

VIVEK CHIBBERI think that you can say we’re deglobalizing if by that we mean that the continuing expansion and integration of the global economy is coming to an end. It’s not that the integration is coming to an end, but the continuing expansion of the integration is coming to an end. And that actually, if we understand deglobalization to mean that it’s actually been underway for about fifteen years now, since the 2008 crisis.

What we see since the 2008 crisis is the level of integration — if we measure it quantitatively — of the global economy has flattened out. From about 1980 to 2010, it was moving upward. The global economy was becoming more and more and more integrated. At around 2010, it leveled out, which means it didn’t disintegrate, it didn’t dismantle the integration, but it just entered a holding pattern with the existing level of integration remaining more or less the same.

That means an end to the expansion of global integration. Is it possible that we could actually start seeing a reduction in the degree of integration? It’s definitely possible. But if I had to guess, I would say what we’ll see is a slight reduction in the level of integration and then a new plateauing out. That is to say, you won’t see a continuing deglobalization over time. What you’ll see is a ratcheting downward of the level of integration and then plateauing after a point. And the reason for that is simple: the degree of integration is so great that unwinding it so that you have a substantial return to national isolated economies would be so disruptive that governments wouldn’t be able to sustain it.

MELISSA NASCHEKDo you think that Trump’s trade policies are at all responsible for this dynamic?

VIVEK CHIBBERYeah, for sure. It’s been a cataclysmic event. Now, it’s still early in the game and Trump has backtracked on so much of what he’s done. But you know it’s in typical Trump fashion. He raised the tariffs to ungodly levels so it seemed like we were going to have a global catastrophe, and now he scaled it back to simply really high levels, which don’t appear to be cataclysmic, but they’re still quite high by historic standards.

And nobody knows where it’s going to end up. But we have to expect a distinct possibility of some degree of winding down of that integration.

MELISSA NASCHEKThe extent to which I’ve heard speculation about where we’ll end up is just this vague, ominous “we can’t go back” and that kind of goes hand in hand with this comment about how Trump has irreparably damaged America’s reputation. Going back to our episode on soft power, the implication there is that what Trump is really doing is essentially unraveling the American Empire, and that’s then posed as another data point to say: “Well, look, neoliberalism’s definitely ending because neoliberalism has always coexisted with American Empire.”

VIVEK CHIBBERThere’s a certain amount of confusion, and that’s because neoliberalism has become this catchall that encompasses everything. So I think there is a scaling back of the American Empire, but it’s not because of Trump. I said this several episodes ago: what Trump is doing is simply recognizing a fact, which is that American geopolitical power is no longer unchallenged the way it was thirty or forty years ago. Geopolitical power ultimately rests on economic dominance and American economic dominance in the global economy is simply not what it was forty years ago.

There are countries now that succeeded in moving up the economic ladder globally. China is the best example, but not just China. In Latin America, economies like Brazil. You have South Asia, the Indian economy. You have obviously Russia, which has managed to fend off all of Europe coming to the aid of Ukraine.

All of this shows that the United States can’t just unilaterally call the shots anymore in the global economy, and that means then that it has a choice: it can either continue with the fantasies of the kind that Biden had, which is that you’re going to remain a global political hegemon, even though economically you just can’t call the shots anymore. Or you bring down your global political ambitions in line at the same scale as your economic ambition, as your economic capacity.

We are still in the era of the unchallenged dominance of capital. The fact that it’s experimenting with new institutional forms should not delude us.And I think if it hadn’t been Trump, if it had been anybody else, they would’ve had to do the same thing. The US just can’t call the shots anymore. So there is a scaling back of America’s reach globally. Does that mean the American Empire is shrinking? Yeah, it has to, because empire is simply your influence over other countries — that’s going to shrink. There’s no way around that.

Does that mean that American imperialism is ending? Absolutely not. It’s just going to be a weaker imperialist power than it was forty or fifty years ago. So when we say tariffs are bringing about an end or a dismantling of one aspect of neoliberalism, does that mean that the tariff regime is something American workers should support? The answer is no, not really because it goes back to the point I made earlier, which is neoliberalism is not the issue. The issue is do working people have any real say in what’s going on around them? What tariffs are really a gift to is not workers, but to capital. What tariffs do is decrease the amount of competitive threats that employers face from their rivals in other parts of the world.

Now that is a gift to the employers. There is a section of the Left that thinks if you somehow bring back manufacturing, that will mean you can unionize again. It does not. If you just look at these new workshops of the world, whether they’re in China or in parts of India or in parts of Latin America, where capital has flowed in the last twenty years to revive manufacturing over there or to build manufacturing, those are workshops from hell.

The working conditions there are worse than we’ve ever seen in manufacturing anywhere in the world. Worse than the nineteenth-century manufacturing that you saw in England and Germany. Manufacturing does not mean the revival of trade unions. Organizing means the revival of trade unions, and the fact of the matter is the corporate class has learned from the last eighty years how to immunize itself from organizing efforts within manufacturing as well. They’re about four, five decades ahead of the Left, which still lives in this fantasy world of 1930s and ’40s, where if you could just have manufacturing, you’ll repeat the histories of the ’30s and ’40s. You will not, because the forms of managerial power and control have evolved astronomically since that era.

We’re going to have to come up with entirely new organizing strategies, even in manufacturing. So even if the Trump tariffs bring back some degree of manufacturing to the US, which they probably will to some degree, it doesn’t mean it’s going to bring back trade unions. That depends on organizers learning the new landscape — not just in the services but also in manufacturing.

There’s no reason to assume that, in this new landscape, bringing back manufacturing raises the likelihood of trade unions and organizing trade unions. There’s simply no reason to believe that because the power, the managerial forms of control in manufacturing are completely different than what they were in the 1930s. We’re going have to reinvent what organizing means, which means then “the end of neoliberalism” internationally in the global regime should not be seen as a panacea or even as a gift to the Left or to workers per se. It is, in the first instance, a gift to capital.

We are still in the era of the unchallenged dominance of capital. The fact that it’s experimenting with new institutional forms should not delude us.

MELISSA NASCHEKSo is what you’re saying that there have been some significant political changes over these past ten years or so — while our politics have been so heavily characterized by Trump and his presence — but those changes have not actually altered the fundamental power dynamics in society, they’ve just been instituted to reinforce them?

VIVEK CHIBBERThere are signs of a ruling class and a political establishment that’s very anxious. That’s worried about the fact that the tranquil waters of a pacified and dejected and cynical population can no longer be taken for granted. So they’re experimenting with new social institutions and economic institutions that might do two things: in some way quell all of the anger and the resentment within the population, but secondly, still preserve the basic power imbalance between the holders of wealth and the rest of the population.

And what we as leftists should not do is be confused by the fact that they’re using the rhetoric of anti-neoliberalism and the rhetoric of anti–free trade. We shouldn’t confuse that with the rhetoric of social empowerment. For that, it’s never going to come from on high. It’s never going to come from the right wing lifting the scales from its eyes and saying, “Well, now we want to be a party of the working class.”

That’s only going to come if working people and ordinary citizens impose on these power centers their own vision of what a more democratic society would look like, and insist that the institutions that they’re building be free of the control of the employers, free of the control of their corporate and political overlords, and be subject to their own dictates, their own democratic decision-making. None of that is on the agenda in all of this right-wing populism, even in the Democratic Party’s populism.

Because as I said earlier, the fight right now between the Democrats and the Republicans is the Democrats want a more multiracial, a more socially heterogeneous political class that rules over people, and the Republicans are happier with a whiter, more traditional political class that rules over people. Neither of these two parties is thinking about the bottom 80 percent of the population.

And until that happens, you might get a move away from what’s called neoliberalism, which is the rule of markets. But you won’t get a move away from class dominance of the wealthy and the elites over the population, because they can do it through a variety of different institutions, only one of which is free markets.

https://jacobin.com/2025/06/neoliberalism-populism-trump-tariffs-economy

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

armada...

US President Donald Trump said on Thursday that he is sending an “armada” towards Iran, threatening Tehran against resuming its nuclear programme.

Speaking to reporters aboard Air Force One after returning from meetings with world leaders in Davos, Switzerland, Trump said Washington was closely monitoring Iran as US naval assets moved into the region.

“We have a lot of ships going that direction, just in case,” Trump said. “I’d rather not see anything happen, but we’re watching them very closely.”

He added: “We have an armada heading in that direction, and maybe we won’t have to use it.”

US officials, speaking anonymously to Reuters, said the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln and several guided-missile destroyers were expected to arrive in the Middle East in the coming days.

One official said Washington was also considering deploying additional air defence systems to protect US bases from potential Iranian retaliation in the event of an American strike.

The deployments expand Trump’s military options and follow a US attack on Iranian nuclear facilities in June.

The summer strikes were widely seen as a violation of international law.

The warships began moving from the Asia-Pacific last week as tensions rose following a crackdown on protests across Iran. Tehran has accused Washington of encouraging the unrest.

Trump has repeatedly threatened intervention warning Iran against killing protesters, but in the end US strikes were called off. Demonstrations appeared to ease last week.

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei said “several thousand” people were killed during weeks of nationwide protests.

Trump claimed on Thursday that Iran had cancelled nearly 840 executions after US warnings.

“I said, ‘If you hang those people, you’re going to be hit harder than you’ve ever been hit,’” Trump said. “It’ll make what we did to your nuclear programme look like peanuts.

He said the executions were cancelled an hour before they were due to take place, calling it “a good sign”.

Iran’s top prosecutor Mohammad Movahedi, however on Friday dismissed Trump's claim suggesting the judiciary had authorised mass executions, calling the allegations baseless.

Speaking in comments carried by the judiciary’s Mizan News Agency, Movahedi said “this claim is completely false; no such number exists, nor has the judiciary made any such decision”.

Trump also repeated his warning that the US would strike again if Iran restarted its nuclear programme.

“If they try to do it again, they have to go to another area. We'll hit them there too, just as easily,” he said.

Protests in Iran began on 28 December with demonstrations over economic hardship in Tehran’s Grand Bazaar before spreading nationwide.

An Iranian official told Reuters that the confirmed death toll had exceeded 5,000, including 500 members of the security forces.

https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/trump-says-us-armada-moving-towards-iran-amid-renewed-threats

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

LET'S HOPE TRUMP'S ARMADA MEETS THE FATE OF THE SPANISH ARMADA...

US porkies....

DEBUNKING THE US NARRATIVE ON VENEZUELA

The US war on Venezuela has been waged not just with weapons and sanctions, but also with words and ideas. Host Michael Fox looks at the misconceptions, myths, and misinformation that have been spread about Venezuela in the wake of the US invasion. This is episode 4 of Under the Shadow, Season 2.

In the hours after the Jan. 3 US invasion of Venezuela, social media was inundated with fake videos and images. Some showed Venezuelans holding huge rallies in favor of the US invasion. Others showed US troops landing or firing from helicopters. Others showed Maduro being kidnapped.

Not all were AI. Some were old, showing anti-government rallies from years past. Or from other places—other invasions or bombing raids, unrelated to the current US attack.

But these videos racked up tons of views, misleading millions of people about what was happening on the ground. Many of those people still don’t know the truth.

It was only the tip of the iceberg.

Today, host Michael Fox looks at the misconceptions, myths, and misinformation that has been spread about Venezuela in the wake of the US invasion and, together with political scientist Steve Ellner, dives headfirst into the biased reporting and slanted truths that have underpinned the mainstream narrative on Venezuela in recent weeks, years, and decades.

Under the Shadow is an investigative narrative podcast series that walks back in time, telling the story of the past by visiting momentous places in the present. Season 2 responds in real time to the Trump administration’s onslaught on Latin America.

Hosted by Latin America-based journalist Michael Fox.

This podcast is produced in partnership between The Real News Network and NACLA.

Theme music by Monte Perdido and Michael Fox. Monte Perdido’s new album Ofrenda is now out. You can listen to the full album on Spotify, Deezer, Apple Music, YouTube or wherever you listen to music.

Other music from Blue Dot Sessions.

Guests

Steve Ellner

Tal Hagin

Script editing by Heather Gies

Hosted, written, and produced by Michael Fox.

Resources

Support Under the Shadow

Please consider supporting this podcast and Michael Fox’s reporting on his Patreon account: patreon.com/mfox. There you can also see exclusive pictures, video, and interviews.

You can check out Michael’s recent episode of Stories of Resistance about the protests against US intervention in Venezuela.

he following is a rushed transcript and may contain errors. It will be updated.

MICHAEL FOX [NARRATION]: There’s this really powerful video that was posted to social media a couple of weeks ago in the days following the US invasion of Venezuela.

In it, huge crowds cheer in the streets. They wear Venezuelan colors: red, blue and yellow. An elderly woman is draped in the Venezuelan flag. She cries in front of the camera.

“The people are finally free,” says a voice off screen. “Thank you to the United States for freeing us. Long live freedom,” he says.

In another clip in this video montage, the same elderly woman speaks to the camera in front of a sea of cheering people. “The monster is gone,” she says. “We are finally free. Thank you, Donald Trump.”

In another pair of clips, two separate bare-chested young men speak very similar words. One with a goatee cheers into the camera as he walks with a crowd… “The dictator has finally fallen,” he shouts. “This is real.”

But it’s not real. The video is fake. AI generated. You can tell from the glitches and the inconsistencies in the Venezuelan flag.

But as of the day after the invasion, one post of that video on X had been retweeted 38,000 times, including by Elon Musk. It had 115,000 likes and 3.6 million views.

This was just one of countless examples of viral content shared in the hours and days following the US invasion of Venezuela that was false, manipulated, or AI generated.

Like that picture you probably saw of the capture of President Nicolás Maduro’s capture. He’s flanked by two US soldiers in camo gear. One with a patch of the American flag. The other with “DEA” written on his chest.

Yeah, that was fake, too. AI generated.

“What happened in Venezuela was a crisis. Any crisis brings with it a lack of information. And when there’s a lack of information, that vacuum needs to be filled. And that’s filled by whatever people can latch onto.”

Tal Hagin is a media literacy educator and an AI-fact checking watchdog on social media.

“And if people are telling you that Maduro was captured, then what do they want to see? A photo of Maduro captured. And so people are going to supply that for you. And so that what happened is an AI creator made an image of Maduro captured. He didn’t say that it was real. He also didn’t say that it was fake. And you just spread it online. And that that went like wildfire all over the internet. I was able to track down the original person who uploaded it and was able to prove that it was AI generated.”

Tal says much of the fake content like this that was created and spread online following the US invasion was done by people trying to rack up views, clicks, likes, and followers. Influencers trying to capitalize on the media frenzy. And other fake content came from people with a political goal of influencing opinions or… “The other was individuals who were simply in support of what had occurred in Venezuela against Maduro. So they were trying to exemplify what had happened against him.”

There were countless images like this.

Like a picture showing Hugo Chávez’s mausoleum in rubble. Tal was able to prove that one too was a fake.

And there were many, many more videos.

Videos showing huge rallies in favor of the US invasion. Videos showing US troops landing or firing from helicopters. Images showing Maduro’s kidnapping.

Not all were AI. Some were old, showing anti-government rallies from years past, for instance. Or from other places — Other invasions or bombing raids, unrelated to the Jan. 3 US attack on Venezuela.

But these videos racked up tons of views, misleading millions of people about what was happening on the ground inside Venezuela.

Many of those people still don’t know the truth.

Here’s another example. A crowd of people cheer and cry in a packed street. Their hands are raised. Voices shout: “The dictatorship’s over. Venezuela is free.”

This one is, of course, also AI.

In fact, it was reportedly created and originally shared by an Instagram account whose bio states that it only uploads AI videos. But then the video was reshared by an influencer on TikTok with 80,000 followers. Her title read, “What the mainstream media won’t show you.”

In other words, she insinuates the video is real. That Venezuelans poured into the streets to applaud the US invasion and Maduro’s kidnapping. Her video is still up — And it has thousands of likes.

Most of these videos and photos are still up… Boosting the narrative that Venezuelans in Venezuela support the US invasion. A line that the Trump administration is happy to have catch fire online.

But in reality… The exact opposite was true.

As the bombs fell on Caracas…. People were terrified. And by the next morning…

Maduro supporters had hit the streets to protest against the invasion. Not in favor of it.

Those protests have continued over the weeks since.

Unions and workers marched in a large rally in the middle of January.

That is not to say that some Venezuelans haven’t celebrated Maduro’s kidnapping. Particularly abroad. That’s the sound of a march of Venezuelans in Quito, Ecuador.

But in Venezuela, mass crowds haven’t hit the streets to applaud the US invasion.

It’s an example of just one of the misconceptions, myths, and misinformation that has been spread about Venezuela in the wake of the US invasion.

And today, I’m going to dive headfirst into the biased reporting and slanted truths that have underpinned the mainstream narrative on Venezuela in recent weeks, years, and decades.

That…. In a minute.

[THEME MUSIC]

This is Under the Shadow — An investigative narrative podcast series that looks at the role of the United States abroad, in the past and the very present.

This podcast is a co-production in partnership with The Real News and NACLA.

I’m your host, Michael Fox — Longtime radio reporter, editor, journalist. The producer and host of the podcasts Brazil on Fire and Stories of Resistance. I’ve spent the better part of the last 20 years in Latin America.

I’ve seen firsthand the role of the US government abroad. And most often, sadly, it is not for the better: Invasions, coups, sanctions. Support for authoritarian regimes. Politically and economically, the United States has cast a long shadow over Latin America for the past 200 years. It still does.

This is Season 2 of Under the Shadow: “Trump’s Attack.”

If you listened to Season 1 about the US role in Central America, you know that in each episode I take you to a location where something historic happened, diving into the past to try and decipher what it means today. I’ll still do that here. But Season 2 is also going to be a little different. Because my goal is to respond in real time to the Trump administration’s onslaught in Latin America.

Just in recent months, we’ve seen the boat strikes, threats, the seizure of multiple tankers carrying Venezuelan crude, US intervention in the Honduran elections, tariff war, the US invasion of Venezuela, and the threat of US attacks on several of Venezuela’s neighbors.

That’s not to mention everything happening in the United States. The ICE raids have detained tens of thousands of people. And they’ve largely targeted Latin American workers and families, among other immigrant groups.

In this podcast series, I look at it all. I walk back in time to understand the present.

Today…. I’m going to take a deep dive into the myths, the lies, the misinformation and disinformation spread about Venezuela… Past and present.

This is Episode 4 — “Debunking Venezuela.”

[MUSIC]

Before I begin today, I should probably say that I first began reporting on Venezuela more than 20 years ago. In large part, I wanted to report about the country because international coverage was so biased. It largely ignored the realities on the ground, in particular for the poorest, working class Venezuelans. Instead, international news outlets dedicated page after page of newsprint to the so-called battle between then-US President George W. Bush and Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez.

Fast-forward to today. It’s still the same story. Just the names have changed. Now, it’s Trump versus Maduro. And it’s gotten way more violent. The threats of years past have become reality. Meanwhile, everyday Venezuelans are relegated to the sidelines. Ignored and portrayed as pawns.

That’s why I co-authored a book back in 2010 called Venezuela Speaks! It’s also why I’ll be spending the entire next episode speaking with folks on the ground about how they have been impacted by the US invasions. What they experienced. What they felt. And what it means now.

But today, I want to dissect some of the most common tropes and misinformation that’s spread about Venezuela.

Not just the fake news or AI images online. But also the entire mainstream media narrative about Venezuela over the last 20 years, going back to the beginning of the government of Hugo Chávez, President Nicolás Maduro’s predecessor.

I think it’s fascinating that this line that, since the late 1990s, Venezuela has been a dictatorship, that kicked out foreign oil companies and ran oil production into the ground… Well, it isn’t just pushed by right-wing outlets like Fox News or even mainstream outlets like The New York Times. It’s shared and reinforced by people who are genuinely trying to do their best to set the record straight.

Here’s just one example.

A friend sent me this video.

It was posted by someone on TikTok with millions of followers. She does these viral videos in front of a chalk board.

I’m not going to mention her handle, because to be honest… I really like what she does. She’s good. I get why she has a lot of followers. She’s funny. She’s witty. She’s scrappy. I watched several of her videos. It’s clear that she herself is trying to debunk mainstream narratives and get at the real motives behind Trump’s invasion of Venezuela, or whatever she’s talking about.

But when it came to Venezuela, in this video, she made many of the same mistakes we’ve heard over and over again.

She said former President Hugo Chávez was a dictator. He was actually reelected in numerous certified free and fair elections. She said he nationalized the country’s oil in the mid 2000s. It was actually nationalized in the 1970s, decades before Chávez and Maduro. And this isn’t just nuance. This is really important to Trump’s myth about Venezuela, his justifications for his invasion, and the threats he continues to hold over the country today.

Remember that Maduro’s former Vice President Delcy Rodríguez is now leading the country as interim president. But she’s been making concessions to Trump as the US president has promised to invade again if she gets out of line. US intervention in Venezuela didn’t end with the attack on Jan. 3. It’s ongoing.

Anyway, my point is this: This influencer’s TikTok video on Venezuela, it has more than 20 million views — 20 million.

And… Look. She did get some things right: That Trump’s invasion was about money and, of course, oil. She even got into US funding for opposition groups in Venezuela, including one founded by opposition leader, Marina Corina Machado, who won the Nobel Peace Prize last year for her fight to overthrow the Venezuelan government.

But she still repeated the same narrative that’s been repeatedly drilled into us.

And hers was only one of numerous videos like this posted online in recent weeks.

And so… In an effort to untangle the truth from the lies and the misinformation, I reached out to Steve Ellner.

STEVE ELLNER [CLIP]: I arrived in Venezuela in 1975 to do research for my PhD dissertation. It was on organized labor in Venezuela from 1936 to 1948. I ended up staying teaching at the Universidad de Oriente in Puerto La Cruz…

MICHAEL FOX [NARRATION]: He would teach at that university for roughly the next 50 years. Today, he’s an associate managing editor of the journal Latin American Perspectives: A Journal on Capitalism and Socialism. His focus is on Latin American politics and, of course, Venezuela.

I have spoken with him twice since the US invasion at the beginning of this month. My interview with him is taken from those conversations.

MICHAEL FOX: Steve, again, thank you so much for joining me today. I really, really appreciate it.

So, I’ve been seeing a lot of videos online of people, supposed experts, saying that they are going to explain in three minutes what’s going on in Venezuela. And then it ends up that they end up just repeating the same kind of mainstream narratives about Venezuela, saying that Chávez was a dictator, that Chávez stole the oil, and that’s why the United States is now invading. Have you been seeing this, and why do these narratives persist?

STEVE ELLNER: Yeah, I’ve certainly seen it, and I’ve polemicized with it. And it’s not only people who know little about Venezuela. I mean, there are academics who know a lot about Venezuela who are saying things along similar lines. And there’s this… Feeling, this urge on the part of the people who write about Venezuela and talk about Venezuela to have to say each time they they they make reference to Maduro to call him a dictator, or to make sure that they clearly indicate that they realize that Venezuela, the Venezuelan government under Maduro, was repressive. Sometimes they compare Maduro with Chávez, other times they say both Maduro and Chávez were repressive.

This comes from the media because the media, every time they refer to Maduro, they call him dictator, dictator. Every time. I did a Google check to see whether they had the same policy towards el-Sisi in Egypt, who is the most repressive leader. It’s the most repressive government in the history of that country. And they don’t do that.

They don’t do that if we go to Saudi Arabia. They call Saudi Arabia a kingdom, not a dictatorship. So that in itself is deceptive. The other aspect of that, Mike, is that there is not a recognition of the relationship between the war… what I call the war in Venezuela that goes back to Chávez, but was really intensified under Maduro, with the Guarimba, with the assassination attempts, with the use of drones, the paramilitary invasion from Colombia, the recognition of Juan Guaido, the intensification of the sanctions.

So there’s a relationship between that and the democracy that exists in Venezuela. War and democracy are incompatible. There’s no question about it. I mean, history bears that out. It was the case during World War I. It was the case during World War II. And this war in Venezuela has really limited options so that when we’re talking about the Venezuelan government, OK, there has been situations of repressive activity. There’s also been violence employed by the opposition or sectors of the opposition. So it’s more complicated than that.

But this urge to say, every time they talk, they make reference to Maduro, or every time they begin to talk about the Venezuelan situation, they feel compelled to indicate that they realize that Venezuela is not democratic or not as democratic as it was under Chávez, etc.

So I think that’s deceptive because it’s not contextualizing what’s really taking place and what’s taken place in Venezuela practically since Chávez first came to office in 1999.

The second thing is that The New York Times and other centrist media are making reference to the colectivos in Venezuela. They paint a picture that Maduro maintained himself in power because of some kind of alliance with guerrillas on the border, the Colombian guerrillas, the ex-FARC combatants, and the ELN, which spilled over to Venezuela. The colectivos, which are referred to practically as paramilitary groups that Diosdaro Cabello supposedly controls.

MICHAEL FOX: Diosdado Cabello has long been a top official in the Venezuelan government. Currently he’s minister of interior. The colectivos are these pro-Chávez community groups that are sometimes armed.

STEVE ELLNER: And so that that also gives the impression that Maduro maintained himself in power through repression, basically, through fear. But the fact of the matter is that what happened on Jan. 3 is a demonstration that the narrative that the media bought into and the narrative that Maria Corina Machado is still articulating is that narrative is completely false.

Maria Corina Machado just yesterday, or at least like I heard her yesterday speaking. She was invited by the by the Heritage Foundation out of all people.

And she talked about what Jan. 3 represented. It represented, according to her, the triumph of the Venezuelan people, a demonstration that the Venezuelan people are united against dictatorship.

It was a victory for this commitment on the part of her group and support on the part of the vast majority of the Venezuelans for democracy, which means, in effect, the rule of Maria Corina Machado and Edmundo Gonzalez. But the fact of the matter is that what the media anticipated in the first couple of days there was that there’d be some kind of uprising, some kind of movement, mobilization inspired by US intervention in Venezuela. And that didn’t take place at all. Not at all. There was no mobilization, or very little mobilization on the part of the opposition. And in contrast, the government, the Chavista government, and Delcy Rodríguez in particular, they mobilized their people in demanding the release of Maduro and the First Lady,

Cilia Flores, demanding that the United States stay out of Venezuela. These mobilizations were fairly massive. So the contrast between the inability of the radical opposition to mobilize their people… on the one hand, the contrast between that and the ability of the Chavistas to mobilize their people in support of Celia Flores and Nicolás Maduro is quite stark.

It demonstrates that that narrative that Machado has the support of the vast majority of Venezuelans is completely false.

MICHAEL FOX: Steve, I cannot let pass this moment without mentioning Machado’s visit to the White House, where she handed over, as she said she was going to, she handed over her Nobel Peace Prize to Trump. What is your what is your take on this?

STEVE ELLNER: It’s really pathetic when you when you consider it. And that she is using this in order to bolster her position, I mean, her hope is obviously she is not satisfied and sectors of the opposition have stated and right-wingers here in the United States have also stated that it’s unfortunate that Trump didn’t go full-fledged in ousting the Chavistas from power.

But this is obviously what she wants. And so she’s using this so-called peace prize in order to further her interests, which are political, her interests are to have Trump remove Delcy Rodriguez from power and so that you know her people can return to Venezuela and take over the government.

So it’s quite you know cynical on her part, this symbolic move of handing over the Peace Prize to Trump in order to further her interests.

MICHAEL FOX: Steve, I’ve been seeing some stuff about members of the opposition who have come out, who maybe don’t like Maduro, but they’ve come out denouncing the invasion. Have you seen anything like to that extent? Because obviously we’ve also seen people in particularly Venezuelans abroad celebrating Trump’s maneuvers. I mean, obviously Maria Corina Machado, but also other people. But have you seen very much of like, do we know where the opposition stance is? I’m sure it’s divided, but in in terms of the actual US invasion itself.

STEVE ELLNER: The fact that Capriles criticized, maybe not in, is not as adamantly, as the Chavistas, but he criticized the US military presence of the Caribbean is an indication of where he stands.

MICHAEL FOX: Capriles Radonski is a long-time member of the Venezuelan opposition. The former governor of the Venezuelan state of Miranda and a National Assembly representative.