Search

Recent comments

- 2019 clean up before the storm....

31 min 34 sec ago - to death....

1 hour 10 min ago - noise....

1 hour 17 min ago - loser....

3 hours 57 min ago - relatively....

4 hours 19 min ago - eternally....

4 hours 25 min ago - success....

14 hours 53 min ago - seriously....

17 hours 37 min ago - monsters.....

17 hours 44 min ago - people for the people....

18 hours 21 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

a militaristic propaganda piece of a special kind.......

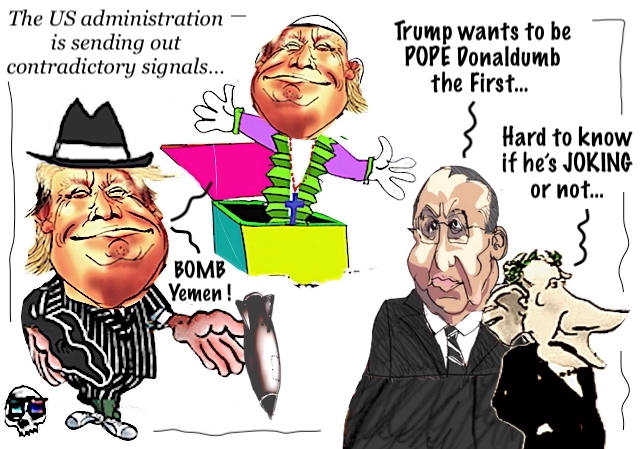

The hope, shared among many, that replacing the Biden government would increase the chances of peace in Europe is rapidly fading. The war obsession among Europe’s power elites is at this point unremitting. The European public is inundated with a relentless wave of propaganda. The new US administration is also sending out contradictory signals and is by no means consistent in its efforts to correct its aggressive course.

The Western strategy of escalation is threatening mankind

by Karl-Jürgen Müller

On 29 March 2025, The “New York Times” published a very long article on the involvement of various NATO states in the Ukraine war, chief among these the US.1 When reading the article, you need to arm yourself, because it not only shows how the war in Ukraine was directed and escalated from the large base the US maintains in Wiesbaden with ever more and ever more destructive weapons. The text, headlined “The Partnership,” is also a militaristic propaganda piece of a special kind. The reporter reveals himself to be an admirer of US support for the war – even as Russia has mourned large numbers of casualties and the US leaders have scored a coup.

The article suggests that the military situation in Ukraine is now precarious is not the fault of US officers and intelligence operatives but is the consequence, above all, to the Kiev regime’s failure to heed US “recommendations” – this and an insufficient supply of U.S. weapons. The message of the article is clear: The war must go on!2

The fact that Europe’s new “coalition of the willing,” with its delusion of a “Russian threat,”3 wants to increase its war efforts and invest trillions of euros in arms raises the question: While this coalition’s propaganda formula has it that Europe will be on its own in the future and will have to make enormous efforts to become “war-ready” against the Russian “aggressor,” aren’t Europe’s militaries still reliant on the war machine on the other side of the Atlantic? Isn’t this more about increased burden-sharing? The Europeans are supposed to “deter” (Newspeak for defeat) the “enemies” in Europe and the Americans in other regions of the world: West Asia, Southeast Asia, the Arctic.

Nuclear brinksmanship during the Cold War

Hardly anyone remembers that the Western strategy of escalation to defeat its purported enemy failed twice during the Cold War. Nor do many of us understand that the West’s narrative of Cold War victory without a fight through a policy of strength is highly questionable – and very dangerous.

Many people still remember the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, when the U.S. provoked the deployment of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba, not least by deploying nuclear missiles in Turkey, a neighbour of the Soviet Union. The U.S. government initially opted for escalation. At the time, humanity narrowly escaped nuclear war: “It was luck that prevented nuclear war!” Robert McNamara, the defence secretary at the time, later reflected. The conclusion of the American and Soviet leadership at the time, John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev, was that in the age of nuclear weapons, the strategy of escalation is a dead end that threatens humanity and that détente and peaceful coexistence, despite different social systems, does not amount to appeasement, a prevalent term among the propagandists at the time and an obvious reference to the Munich Agreement of September 1938. No, it was simply a survival imperative.

Renewed escalation: The late 1970s and early 1980s

It is almost unknown that a similar scenario was repeated in the early 1980s, when a nuclear catastrophe was once again very narrowly avoided. This prompted another rethink in the East and the West alike. Out of this came the arms agreements Mikhail Gorbachev and Ronald Reagan signed in the second half of the decade.

What had happened? The lessons of the early 1960s no longer seemed appropriate for US policy in the late 1970s and early 1980s. By that time the US – with the significant involvement of Zbigniew Brzezinski, President Carter’s national security adviser – had wanted to torpedo European, and above all German, policy of détente towards the East. The Soviet Union was to be lured into a trap (Afghanistan), not only to give the Soviet Union “its version of the Vietnam quagmire,” but also to revive the pre-détente Cold War atmosphere in the West.

This was no longer simply a matter of securing the status quo the balance of power: Washington’s aim was to become the world’s sole superpower. This was because it was now believed – primarily thanks to America’s superiority in economic development and in weapons and information technology – that the U.S. could win the Cold War despite the Soviets’ nuclear-weapons inventory. Dirk Pohlmann’s television documentary “Täuschung: Die Methode Reagan” (Deception: The Reagan Method), broadcast in 2013, gives impressive evidence of this.4

1983 and “Able Archer”

The high point of escalation was in 1983. The events of that year were, indeed, the historical background for a multi-part television film series in 2015: Deutschland 1983.5

In an instantly famous speech delivered on 8 March 1983, President Reagan called the Soviet Union the “evil empire.” On 23 March, he announced the start of the Strategic Defence Initiative, the missile defence programme known as S.D.I., which the Soviets saw as an attempt to undermine the established balance of armaments. In June, the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Yuri Andropov, warned the US Ambassador, Avril Harriman, the US and the Soviet Union were ‘moving towards a red line’ – a miscalculation could trigger a nuclear war.

The Soviet Union had long feared a U.S. nuclear first strike. Reflecting its anxiety, on 1 September, Soviet fighter jets shot down a South Korean passenger plane after KAL 007 deviated from its flight path and entered Soviet airspace. From 19 to 30 September, NATO carried out an annual large-scale manoeuvre, Reforger, which involved 65,000 soldiers. On 26 September, a Soviet control centre 90 kilometres south of Moscow reported the alleged launch of a U.S. nuclear missile towards the Soviet Union. It was thanks to a level-headed officer, Colonel Stanislav Petrov, that an automatic counterattack was prevented. At the end of October, and after failed negotiations with the Soviet Union, NATO decided to station medium-range nuclear weapons in Germany as of December 1983, as the alliance had threatened in the Double-Track Decision of 1979. This considerably reduced the warning time for the Soviet Union.

On 7 November, NATO secretly began a realistic simulation of a Western nuclear strike against the Soviet Union. This was named Able Archer, a commando exercise that became public only five years later. Even before the exercise, however, agents of the Warsaw Pact, who had been increasingly infiltrating NATO since 1981, had learned about the exercise and triggered an alarm in the Soviet Union with their reports. Moscow assumed that Able Archer was not an exercise but the prelude to the feared Western nuclear first strike. The consequence: Soviet nuclear forces were put on alert and prepared for a pre-emptive nuclear strike. Years later, a former GDR agent at NATO headquarters, Rainer Rupp (with the code name Topas), explained that he had just been able to prevent the catastrophe through decisive communications to his command: Able Archer was in fact an exercise; a nuclear first strike was not planned.

Europe at the crossroads again

None of this was known to the public in 1983. If you search for German-language articles about Able Archer, you will find them mainly in 2013, 30 years later.6 But in 2023, 40 years later and with the Ukraine war raging, hardly anyone talks about it. In the English-speaking world, Able Archer had been a topic of discussion earlier, mainly because of the disclosure of previously secret US files. These files were analysed in the greatest detail in the 2016 book by Nate Jones, Able Archer 83: The Secret History of the NATO Exercise That Almost Triggered Nuclear War.

Europe is once again at a crossroads. The Europeans’ new “coalition of the willing”, which is striving for a “war-ready,” highly armed Europe and is trying to justify this with the earlier-noted threat analysis, wants to “defeat” Russia – “to ruin it” (according to Annalena Baerbock), to cause a permanently debilitating “strategic defeat” (according to U.S. and NATO officials). The New York Times article of 29 March, mentioned above, shows what this has meant in concrete terms and that this is not over – as was the case several times during the Cold War. The years 1962 and 1983 have shown where this can lead.

Understanding and peace with Russia are not an appeasement policy. Understanding and peace are not only be possible – they are a survival imperative, just as Kennedy and Khrushchev understood their circumstances in the autumn of 1962. In 1983, millions of people in Europe were aware of the danger of nuclear war. The Doomsday Clock stood at 3 minutes to midnight (midnight = nuclear war). It was a great year for the European and German peace movement. Today, the Doomsday Clock stands at 89 seconds to midnight.

On 1 August 1975, almost 50 years ago and in the middle of the Cold War, after two years of negotiations, all European states (except Albania), the Soviet Union, the U.S., Canada, and Turkey signed the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) in Helsinki. Understanding is possible if there is political will on all sides. Incidentally, neutral Switzerland played an important role at the time.7 Who and what can humanity hope for today? •

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

- By Gus Leonisky at 3 May 2025 - 8:43am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

cardinal trump....

WASHINGTON, April 29 (Reuters) - U.S. President Donald Trump on Tuesday joked that he would like to succeed Pope Francis, who died last week at the age of 88.

Trump, asked about whom he'd like to see become the next Catholic pontiff, told reporters: "I'd like to be pope. That would be my No. 1 choice."

Trump noted he actually had no preference, adding, "I must say, we have a cardinal that happens to be out of a place called New York who’s very good, so we’ll see what happens.”

https://www.reuters.com/world/us/trump-jokes-that-hed-like-be-next-pope-2025-04-29/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

vatican bank.....

Many think of Vatican City only as the seat of governance for the world’s 1.3 billion Roman Catholics. Atheist critics view it as a capitalist holding company with special privileges. However, that postage-stamp parcel of land in the center of Rome is also a sovereign nation. It has diplomatic embassies—so-called apostolic nunciatures—in over 180 countries, and has permanent observer status at the United Nations.

Only by knowing the history of the Vatican’s sovereign status is it possible to understand how radically different it is compared to other countries. For over 2,000 years the Vatican has been a nonhereditary monarchy. Whoever is Pope is its supreme leader, vested with sole decision-making authority over all religious and temporal matters. There is no legislature, judiciary, or any system of checks and balances. Even the worst of Popes—and there have been some truly terrible ones—are sacrosanct. There has never been a coup, a forced resignation, or a verifiable murder of a Pope. In 2013, Pope Benedict became the first pope to resign in 600 years. Problems of cognitive decline get swept under the rug. In its unchecked power of a single man, the Vatican is closest in its governance style to a handful of absolute monarchies such as Saudi Arabia, Brunei, Oman, Qatar, and the UAE.

During the Renaissance, Popes were feared rivals to Europe’s most powerful monarchies.

From the 8th century until 1870 the Vatican was a semifeudal secular empire called the Papal States that controlled most of central Italy. During the Renaissance, Popes were feared rivals to Europe’s most powerful monarchies. Popes believed God had put them on earth to reign over all other worldly rulers. The Popes of the Middle Ages had an entourage of nearly a thousand servants and hundreds of clerics and lay deputies. That so-called Curia—referring to the court of a Roman emperor—became a Ladon-like network of intrigue and deceit composed largely of (supposedly) celibate single men who lived and worked together at the same time they competed for influence with the Pope.

The cost of running the Papal States, while maintaining one of Europe’s grandest courts, kept the Vatican under constant financial strain. Although it collected taxes and fees, had sales of produce from its agriculturally rich northern region, and rents from its properties throughout Europe, it was still always strapped for cash. The church turned to selling so-called indulgences, a sixth-century invention whereby the faithful paid for a piece of paper that promised that God would forgo any earthly punishment for the buyer’s sins. The early church’s penances were often severe, including flogging, imprisonment, or even death. Although some indulgences were free, the best ones—promising the most redemption for the gravest sins—were expensive. The Vatican set prices according to the severity of the sin.

The Church had to twice borrow from the Rothschilds.

All the while, the concept of a budget or financial planning was anathema to a succession of Popes. The humiliating low point came when the Church had to twice borrow from the Rothschilds, Europe’s preeminent Jewish banking dynasty. James de Rothschild, head of the family’s Paris-based headquarters, became the official Papal banker. By the time the family bailed out the Vatican, it had only been thirty-five years since the destabilizing aftershocks from the French Revolution had led to the easing of harsh, discriminatory laws against Jews in Western Europe. It was then that Mayer Amschel, the Rothschild family patriarch, had walked out of the Frankfurt ghetto with his five sons and established a fledgling bank. Little wonder the Rothschilds sparked such envy. By the time Pope Gregory asked for the first loan they had created the world’s biggest bank, ten times larger than their closest rival.

The Vatican’s institutional resistance to capitalism was a leftover of Middle Age ideologies, a belief that the church alone was empowered by God to fight Mammon, a satanic deity of greed. Its ban on usury—earning interest on money loaned or invested—was based on a literal biblical interpretation. The Vatican distrusted capitalism since it thought secular activists used it as a wedge to separate the church from an integrated role with the state. In some countries, the “capitalist bourgeoisie”—as the Vatican dubbed it—had even confiscated church land for public use. Also fueling the resistance to modern finances was the view that capitalism was mostly the province of Jews. Church leaders may not have liked the Rothschilds, but they did like their cash.

The Church’s sixteen thousand square miles was reduced to a tiny parcel of land.

In 1870, the Vatican lost its earthly empire overnight when Rome fell to the nationalists who were fighting to unify Italy under a single government. The Church’s sixteen thousand square miles was reduced to a tiny parcel of land. The loss of its Papal States income meant the church was teetering on the verge of bankruptcy.

The Vatican survived going forward on something called Peter’s Pence, a fundraising practice that had been popular a thousand years earlier with the Saxons in England (and later banned by Henry VIII when he broke with Rome and declared himself head of the Church of England). The Vatican pleaded with Catholics worldwide to contribute money to support the Pope, who had declared himself a prisoner inside the Vatican and refused to recognize the new Italian government’s sovereignty over the Church.

During the nearly 60-year stalemate that followed, the Vatican’s insular and mostly incompetent financial management kept it under tremendous pressure. The Vatican would have gone bankrupt if Mussolini had not saved it. Il Duce, Italy’s fascist leader, was no fan of the Church, but he was enough of a political realist to know that 98 percent of Italians were Catholics. In 1929, the Vatican and the Fascist government executed the Lateran Pacts. It gave the Church the most power since the height of its temporal kingdom. It set aside 108.7 acres as Vatican City and fifty-two scattered “heritage” properties as an autonomous neutral state. It reinstated Papal sovereignty and ended the Pope’s boycott of the Italian state.

The settlement—worth about $1.6 billion in 2025 dollars—was approximately a third of Italy’s entire annual budget.

The Lateran Pacts declared the Pope was “sacred and inviolable,” the equivalent of a secular monarch, and acknowledged he was invested with divine rights. A new Code of Canon Law made Catholic religious education obligatory in state schools. Cardinals were invested with the same rights as princes by blood. All church holidays became state holidays and priests were exempted from military and jury duty. A three-article financial convention granted “ecclesiastical corporations” full tax exemptions. It also compensated the Vatican for the confiscation of the Papal States with 750 million lire in cash and a billion lire in government bonds that paid 5 percent interest. The settlement—worth about $1.6 billion in 2024 dollars—was approximately a third of Italy’s entire annual budget and a desperately needed lifeline for the cash-starved church.

Pius XI, the Pope who struck the deal with Mussolini, was savvy enough to know that he and his fellow cardinals needed help managing the enormous windfall. He therefore brought in a lay outside advisor, Bernardino Nogara, a devout Catholic with a reputation as a financial wizard.

Nogara took little time in upending hundreds of years of tradition. He ordered, for instance, that every Vatican department produce annual budgets and issue monthly income and expense statements. The Curia bristled when he persuaded Pius to cut employee salaries by 15 percent. And after the 1929 stock market crash, Nogara made investments in blue-chip American companies whose stock prices had plummeted. He also bought prime London real estate at fire-sale prices. As tensions mounted in the 1930s, Nogara further diversified the Vatican’s holdings in international banks, U.S. government bonds, manufacturing companies, and electric utilities.

Only seven months before the start of World War II, the church got a new Pope, Pius XII, one who had a special affection for Germany (he had been the Papal Nuncio—ambassador—to Germany). Nogara warned that the outbreak of war would greatly test the financial empire he had so carefully crafted over a decade. When the hot war began in September 1939, Nogara realized he had to do more than shuffle the Vatican’s hard assets to safe havens. He knew that beyond the military battlefield, governments fought wars by waging a broad economic battle to defeat the enemy. The Axis powers and the Allies imposed a series of draconian decrees restricting many international business deals, banning trading with the enemy, prohibiting the sale of critical natural resources, and freezing the bank accounts and assets of enemy nationals.

The United States was the most aggressive, searching for countries, companies, and foreign nationals who did any business with enemy nations. Under President Franklin Roosevelt’s direction, the Treasury Department created a so-called blacklist. By June 1941 (six months before Pearl Harbor and America’s official entry into the war), the blacklist included not only the obvious belligerents such as Germany and Italy, but also neutral nations such as Switzerland, and the tiny principalities of Monaco, San Marino, Liechtenstein, and Andorra. Only the Vatican and Turkey were spared. The Vatican was the only European country that proclaimed neutrality that was not placed on the blacklist.

There was a furious debate inside the Treasury department about whether Nogara’s shuffling and masking of holding companies in multiple European and South American banking jurisdictions was sufficient to blacklist the Vatican. It was only a matter of time, concluded Nogara, until the Vatican was sanctioned.

The Vatican Bank could operate anywhere worldwide, did not pay taxes … disclose balance sheets, or account to any shareholders.

Every financial transaction left a paper trail through the central banks of the Allies. Nogara needed to conduct Vatican business in secret. The June 27, 1942, formation of the Istituto per le Opere di Religione (IOR)—the Vatican Bank—was heaven sent. Nogara drafted a chirograph (a handwritten declaration), a six-point charter for the bank, and Pius signed it. Since its only branch was inside Vatican City—which, again, was not on any blacklist—the IOR was free of any wartime regulations. The IOR was a mix between a traditional bank like J. P. Morgan and a central bank such as the Federal Reserve. The Vatican Bank could operate anywhere worldwide, did not pay taxes, did not have to show a profit, produce annual reports, disclose balance sheets, or account to any shareholders. Located in a former dungeon in the Torrione di Nicoló V (Tower of Nicholas V), it certainly did not look like any other bank.

The Vatican Bank was created as an autonomous institution with no corporate or ecclesiastical ties to any other church division or lay agency. Its only shareholder was the Pope. Nogara ran it subject only to Pius’s veto. Its charter allowed it “to take charge of, and to administer, capital assets destined for religious agencies.” Nogara interpreted that liberally to mean that the IOR could accept deposits of cash, real estate, or stock shares (that expanded later during the war to include patent royalty and reinsurance policy payments).

Many nervous Europeans were desperate for a wartime haven for their money. Rich Italians, in particular, were anxious to get cash out of the country. Mussolini had decreed the death penalty for anyone exporting lire from Italian banks. Of the six countries that bordered Italy, the Vatican was the only sovereignty not subject to Italy’s border checks. The formation of the Vatican Bank meant Italians needed only a willing cleric to deposit their suitcases of cash without leaving any paper trail. And unlike other sovereign banks, the IOR was free of any independent audits. It was required—supposedly to streamline recordkeeping—to destroy all its files every decade (a practice it followed until 2000). The IOR left virtually nothing by which postwar investigators could determine if it was a conduit for shuffling wartime plunder, held accounts, or money that should be repatriated to victims.

The Vatican immediately dropped off the radar of U.S. and British financial investigators.

The IOR’s creation meant the Vatican immediately dropped off the radar of U.S. and British financial investigators. It allowed Nogara to invest in both the Allies and the Axis powers. As I discovered in research for my 2015 book about church finances, God’s Bankers: A History of Money and Power at the Vatican, Nogara’s most successful wartime investment was in German and Italian insurance companies. The Vatican earned outsized profits when those companies escheated the life insurance policies of Jews sent to the death camps and converted the cash value of the policies.

After the war, the Vatican claimed it had never invested or made money from Nazi Germany or Fascist Italy. All its wartime investments and money movements were hidden by Nogara’s impenetrable Byzantine offshore network. The only proof of what happened was in the Vatican Bank archives, sealed to this day. (I have written opinion pieces in The New York Times, Washington Post, and Los Angeles Times, calling on the church to open its wartime Vatican Bank files for inspection. The Church has ignored those entreaties.)

Its ironclad secrecy made it a popular postwar offshore tax haven for wealthy Italians wanting to avoid income taxes.

While the Vatican Bank was indispensable to the church’s enormous wartime profits, the very features—no transparency or oversight, no checks and balances, no adherence to international banking best practices—became its weakness going forward. Its ironclad secrecy made it a popular postwar offshore tax haven for wealthy Italians wanting to avoid income taxes. Mafia dons cultivated friendships with senior clergy and used them to open IOR accounts under fake names. Nogara retired in the 1950s. The laymen who had been his aides were not nearly as clever or imaginative as was he. It opened the Vatican Bank to the influence of lay bankers. One, Michele Sindona, was dubbed by the press as “God’s Banker” in the mid-1960s for the tremendous influence and deal making he had with the Vatican Bank. Sindona was a flamboyant banker whose investment schemes always pushed against the letter of the law. (Years later he would be convicted of massive financial fraud and murder of a prosecutor and would himself be killed in an Italian prison.)

Exacerbating the bad effect of Sindona directing church investments, the Pope’s pick to run the Vatican Bank in the 1970s was a loyal monsignor, Chicago-born Paul Marcinkus. The problem was that Marcinkus knew almost nothing about finances or running a bank. He later told a reporter that when he got the news that he would oversee the Vatican Bank, he visited several banks in New York and Chicago and picked up tips. “That was it. What kind of training you need?” He also bought some books about international banking and business. One senior Vatican Bank official worried that Marcinkus “couldn’t even read a balance sheet.”

Marcinkus allowed the Vatican Bank to become more enmeshed with Sindona, and later another fast-talking banker, Roberto Calvi. Like Sindona, Calvi would also later be on the run from a host of financial crimes and frauds, but he never got convicted. He was instead found hanging in 1982 under London’s Blackfriars Bridge.

“You can’t run the church on Hail Marys.” —Vatican Bank head Paul Marcinkus, defending the Bank’s secretive practices in the 1980s.

By the 1980s the Vatican Bank had become a partner in questionable ventures in offshore havens from Panama and the Bahamas to Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, and Switzerland. When one cleric asked Marcinkus why there was so much mystery about the Vatican Bank, Marcinkus dismissed him saying, “You can’t run the church on Hail Marys.”

All the secret deals came apart in the early 1980s when Italy and the U.S. opened criminal investigations on Marcinkus. Italy indicted him but the Vatican refused to extradite him, allowing Marcinkus instead to remain in Vatican City. The standoff ended when all the criminal charges were dismissed and the church paid a stunning $244 million as a “voluntary contribution” to acknowledge its “moral involvement” with the enormous bank fraud in Italy. (Marcinkus returned a few years later to America where he lived out his final years at a small parish in Sun City, Arizona.)

Throughout the 1990s and into the early 2000s, the Vatican Bank remained an offshore bank in the heart of Rome.

It would be reasonable to expect that after having allowed itself to be used by a host of fraudsters and criminals, the Vatican Bank cleaned up its act. It did not, however. Although the Pope talked a lot about reforms, it kept the same secret operations, expanding even into massive offshore deposits disguised as fake charities. The combination of lots of money, much of it in cash, and no oversight, again proved a volatile mixture. Throughout the 1990s and into the early 2000s, the Vatican Bank remained an offshore bank in the heart of Rome. It was increasingly used by Italy’s top politicians, including prime ministers, as a slush fund for everything from buying gifts for mistresses to paying off political foes.

Italy’s tabloids, and a book in 2009 by a top investigative journalist Gianluigi Nuzzi, exposed much of the latest round of Vatican Bank mischief. It was not, however, the public shaming of “Vatileaks” that led to any substantive reforms in the way the Church ran its finances. Many top clerics knew that as a 2,000-year-old institution, if they waited patiently for the public outrage to subside, the Vatican Bank could soon resume its shady dealings.

In 2000, the Church signed a monetary convention with the European Union by which it could issue its own euro coins.

What changed everything in the way the Church runs its finances came unexpectedly in a decision about a common currency—the euro—that at the time seemed unrelated to the Vatican Bank. Italy stopped using the lira as its currency and adopted the euro in 1999. That initially created a quandary for the Vatican, which had always used the lira as its currency. The Vatican debated whether to issue its own currency or to adopt the euro. In December 2000, the church signed a monetary convention with the European Union by which it could issue its own euro coins (distinctively stamped with Città del Vaticano) as well as commemorative coins that it marked up substantially to sell to collectors. Significantly, that agreement did not bind the Vatican, or two other non-EU nations that had accepted the euro—Monaco and Andorra—to abide by strict European statutes regarding money laundering, antiterrorism financing, fraud, and counterfeiting.

What the Vatican did not expect was that the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a 34-nation economics and trade group that tracks openness in the sharing of tax information between countries, had at the same time begun investigating tax havens. Those nations that shared financial data and had in place adequate safeguards against money laundering were put on a so-called white list. Those that had not acted but promised to do so were slotted onto the OECD’s gray list, and those resistant to reforming their banking secrecy laws were relegated to its blacklist. The OECD could not force the Vatican to cooperate since it was not a member of the European Union. However, placement on the blacklist would cripple the Church’s ability to do business with all other banking jurisdictions.

The biggest stumbling block to real reform is that all power is still vested in a single man.

In December 2009, the Vatican reluctantly signed a new Monetary Convention with the EU and promised to work toward compliance with Europe’s money laundering and antiterrorism laws. It took a year before the Pope issued a first ever decree outlawing money laundering. The most historic change took place in 2012 when the church allowed European regulators from Brussels to examine the Vatican Bank’s books. There were just over 33,000 accounts and some $8.3 billion in assets. The Vatican Bank was not compliant on half of the EU’s forty-five recommendations. It had done enough, however, to avoid being placed on the blacklist.

In its 2017 evaluation of the Vatican Bank, the EU regulators noted the Vatican had made significant progress in fighting money laundering and the financing of terrorism. Still, changing the DNA of the finances of the Vatican has proven incredibly difficult. When a reformer, Argentina’s Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio, became Pope Francis in 2013, he endorsed a wide-ranging financial reorganization that would make the church more transparent and bring it in line with internationally accepted financial standards and practices. Most notable was that Francis created a powerful financial oversight division and put Australian Cardinal George Pell in charge. Then Pell had to resign and return to Australia where he was convicted of child sex offenses in 2018. By 2021, the Vatican began the largest financial corruption trial in its history, even including the indictment of a cardinal for the first time. The case floundered, however, and ultimately revealed that the Vatican’s longstanding self-dealing and financial favoritism had continued almost unabated under Francis’s reign.

It seems that for every step forward, somehow, the Vatican manages to move backwards when it comes to money and good governance. For those of us who study it, while it is a more compliant and normal member of the international community today than at any time in its past, the biggest stumbling block to real reform is that all power is still vested in a single man that the Church considers the Vicar of Christ on earth.

The Catholic Church considers the reigning pope to be infallible when speaking ex cathedra (literally “from the chair,” that is, issuing an official declaration) on matters of faith and morals. However, not even the most faithful Catholics believe that every Pope gets it right when it comes to running the Church’s sovereign government. No reform appears on the horizon that would democratize the Vatican. Short of that, it is likely there will be future financial and power scandals, as the Vatican struggles to become a compliant member of the international community.

https://www.skeptic.com/article/the-vatican-city-city-state-nation-or-bank/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

tacky....

US President Donald Trump has posted an AI-generated image of himself in papal attire, just days after joking about becoming the next pope. The image, shared on his Truth Social platform on Saturday, depicts Trump in white papal robes, a gold crucifix, and a mitre, with his right hand raised in a traditional papal gesture.

The post follows comments Trump made earlier this week to reporters. “I’d like to be pope, that would be my number one choice,” he said in response to questions about potential successors to Pope Francis, who died on April 21. He went on to praise Cardinal Timothy Dolan of New York as “very good,” though Vatican observers note that the election of an American pope is unlikely.

The president and First Lady Melania Trump attended Pope Francis’ funeral in Rome on April 26, which marked his first international trip since returning to office in January.

The AI-generated image sparked mixed reactions online. Some users found it humorous, while others criticized it as inappropriate, accusing Trump of mocking the death of the late pope.

The Vatican has confirmed that the papal conclave to elect a new pope will begin on May 8, with cardinals from around the world convening in the Sistine Chapel to vote in secrecy.

https://www.rt.com/news/616685-trump-shares-image-of-himself-pope/

MEANWHILE:

French President Emmanuel Macron is attempting to influence the upcoming papal conclave in favor of a French candidate to become the next Pope, several conservative Italian media outlets have claimed.

The reports emerged following meetings between the French leader and several cardinal electors, as well as a leader of an influential Catholic movement ahead of the conclave set to determine Francis’ successor.

Macron had lunch with four of the five cardinal electors of French descent, including Jean-Marc Aveline, the archbishop of Marseille, last Saturday on the sidelines of Pope Francis’ funeral. The pontiff passed away on April 21.

Last Friday, the French president also had dinner at a restaurant in Rome with Andrea Riccardi, the head of the Community of Sant’Egidio, a powerful Catholic association with more than 70,000 lay members in 74 countries, and which reportedly has clout over some members of the upcoming conclave.

According to the Italian daily Il Tempo, the French leader asked the cardinals about ways to build a consensus around Aveline. The outlet called the cardinal – who is considered a contender to become the next Pope – an “ultra-European, anti-sovereignist” and “one of the most liberal” members of the conclave.

The daily also described the meetings as an example of “interventionism worthy of a new Sun King,” in an apparent reference to France’s 17th century King Louis XIV, who sought to influence the election of a Pope through French cardinals. Another Italian paper, La Verita, directly accused Macron of seeking to choose the next Pope.

The Elysee Palace did not officially comment on the agenda of the two meetings. The Community of Sant’Egidio denied the allegations, telling Le Monde on Thursday that Macron “seeks to understand the process, not influence it.”

Conservative Italian media linked the president’s actions to his desire to regain international influence and mend ties with the Holy See, which reportedly soured under Pope Francis. These claims caught the attention of French news outlets, including Le Monde, which said their Italian colleagues were spreading “rumors,” reflecting the mutual distrust between Paris and Rome.

A conclave involving 135 cardinals is set to convene at the Vatican on May 7 to elect the next Pope.

https://www.rt.com/news/616672-macron-interfere-papal-conclave-media/

GREAT ! ONE THINKS HE'S THE POPE AND THE OTHER TAKES HIMSELF FOR NAPOLEON....

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

pope donald one....

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MTldEUiX82g

Damon VS Everyone on The View | Best Moments Compilation Vol.13 (Satire)READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.