Search

Recent comments

- 2019 clean up before the storm....

2 hours 7 min ago - to death....

2 hours 45 min ago - noise....

2 hours 52 min ago - loser....

5 hours 33 min ago - relatively....

5 hours 55 min ago - eternally....

6 hours 45 sec ago - success....

16 hours 29 min ago - seriously....

19 hours 13 min ago - monsters.....

19 hours 20 min ago - people for the people....

19 hours 56 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

a new international cooperation.....

Writing in his cell as a political prisoner in fascist Italy after World War I, the philosopher Antonio Gramsci famously declared: “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.” A century later, we are in another interregnum, and the morbid symptoms are everywhere. The US-led order has ended, but the multipolar world is not yet born. The urgent priority is to give birth to a new multilateral order that can keep the peace and the path to sustainable development.

Giving Birth to the New International OrderJEFFREY D. SACHS

We are at the end of a long wave of human history that commenced with the voyages of Christopher Columbus and Vasco da Gama more than 500 years ago. Those voyages initiated more than four centuries of European imperialism that peaked with Britain’s global dominance from the end of the Napoleonic Wars (1815) to the outbreak of World War I (1914). Following World War II, the US claimed the mantle as the world’s new hegemon. Asia was pushed aside during this long period. According to widely used macroeconomic estimates, Asia produced 65 percent of world output in 1500, but by 1950, that share had declined to just 19% (compared with 55% of the world population).

In the 80 years since World War 2, Asia recovered its place in the global economy. Japan led the way with rapid growth in the 1950s and 1960s, followed by the four “Asian tigers” (Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan, and Korea) beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, and then by China beginning around 1980, and India beginning around 1990. As of today, Asia constitutes around 50% of the world economy, according to IMF estimates.

The multipolar world will be born when the geopolitical weight of Asia, Africa, and Latin America matches their rising economic weight. This needed shift in geopolitics has been delayed as the US and Europe cling to outdated prerogatives built into international institutions and to their outdated mindsets. Even today, the US bullies Canada, Greenland, Panama and others in the Western Hemisphere and threatens the rest of the world with unilateral tariffs and sanctions that are blatantly in violation of international rules.

Asia, Africa and Latin America need to stick together to raise their collective voice and their UN votes to usher in a new and fair international system. A crucial institution in need of reform is the UN Security Council, given its unique responsibility under the UN Charter to keep the peace. The five permanent members of the UN Security Council (the P5) – Britain, China, France, Russia, and the United States – reflect the world of 1945, not of 2025. There are no permanent Latin American or African seats, and Asia holds only one permanent seat of the five, despite being home to almost 60% of the world population. Over the years, many new potential UN Security Council permanent members have been proposed, but the existing P5 have held firmly to their privileged position.

The proper restructuring of the UN Security Council will be frustrated for years to come. Yet there is one crucial change that is within immediate reach and that would serve the entire world. By any metric, India indisputably merits a permanent seat on the UN Security Council. Given India’s outstanding track record in global diplomacy, its admission to the UN Security Council would also elevate a crucial voice for world peace and justice.

On all counts, India is a great power. India is the world’s most populous country, having overtaken China in 2024. India is the world’s third largest economy measured at international prices (purchasing-power parity), at $17 trillion, behind China ($40 trillion) and the United States ($30 trillion) and ahead of all the rest. India is the fastest growing major economy in the world, with annual growth of around 6% per year. India’s GDP (PPP) is likely to overtake that of the US by mid-century. India is a nuclear-armed nation, a digital technology innovator, and a country with a leading space program. No other country mentioned as candidate for a permanent UN Security Council member comes close to India’s credentials for a seat.

The same can be said about India’s diplomatic heft. India’s skillful diplomacy was displayed by India’s superb leadership of the G20 in 2023. India deftly managed a hugely successful G20 despite the bitter divide in 2024 between Russia and the NATO countries. Not only did India achieve a G20 consensus; it made history, by welcoming the African Union to a new permanent membership in the G20.

China has dragged its feet on supporting India’s permanent seat in the UN Security Council, guarding its own unique position as the only Asian power in the P5. Yet China’s vital national interests would be well served and bolstered by India’s ascension to a permanent UN Security Council seat. This is especially the case given that the US is carrying out a last-ditch and vicious effort through tariffs and sanctions to block China’s hard-earned rise in economic prosperity and technological prowess.

By supporting India for the UN Security Council, China would establish decisively that geopolitics are being remade to reflect the true multipolar world. While China would create an Asian peer in the UN Security Council, it would also win a vital partner in overcoming the US and European resistance to geopolitical change. If China calls for India’s permanent membership in the UN Security Council, Russia will immediately concur, while the US, UK, and France will vote for India as well.

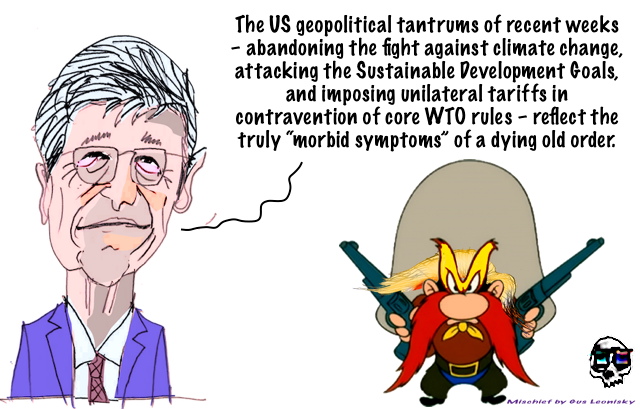

The US geopolitical tantrums of recent weeks – abandoning the fight against climate change, attacking the Sustainable Development Goals, and imposing unilateral tariffs in contravention of core WTO rules – reflect the truly “morbid symptoms” of a dying old order. It’s time to make way for a truly multipolar and just international order.

https://www.unz.com/article/giving-birth-to-the-new-international-order/

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

- By Gus Leonisky at 21 Apr 2025 - 3:20pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

pacific wars....

Bandung ConferenceThe first large-scale Asian–African or Afro–Asian Conference (Indonesian: Konferensi Asia–Afrika), also known as the Bandung Conference, was a meeting of Asian and African states, most of which were newly independent, which took place on 18–24 April 1955 in Bandung, West Java, Indonesia.[1] The twenty-nine countries that participated represented a total population of 1.5 billion people, 54% of the world's population.[2]The conference was organized by Indonesia, Burma (Myanmar), India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), and Pakistan and was coordinated by Ruslan Abdulgani, secretary general of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia.

A 10-point "declaration on promotion of world peace and cooperation", called Dasasila Bandung (Bandung's Ten Principles, or Bandung Spirit, or Bandung Declaration; styled after Indonesia's Pancasila; or Ten Principles of Peaceful Coexistence[22]), incorporating the principles of the United Nations Charter as well as Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence was adopted unanimously as item G in the final communiqué of the conference:[23]

(b) Abstention by any country from exerting pressures on other countries

The final Communique of the Conference underscored the need for developing countries to loosen their economic dependence on the leading industrialised nations by providing technical assistance to one another through the exchange of experts and technical assistance for developmental projects, as well as the exchange of technological know-how and the establishment of regional training and research institutes.

=======

For the US, the Conference accentuated a central dilemma of its Cold War policy; by currying favor with Third World nations by claiming opposition to colonialism, it risked alienating its colonialist European allies.[24] The US security establishment also feared that the Conference would expand China's regional power.[25] In January 1955, the US formed a "Working Group on the Afro-Asian Conference" that included the Operations Coordinating Board (OCB), the Office of Intelligence Research (OIR), the Department of State, the Department of Defense, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and the United States Information Agency (USIA).[26] The OIR and USIA followed a course of "Image Management" for the US, using overt and covert propaganda to portray the US as friendly and to warn participants of the Communist menace.[27]

The United States, at the urging of Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, shunned the conference and was not officially represented. However, the administration issued a series of statements during the lead-up to the Conference. These suggested that the US would provide economic aid and attempted to reframe the issue of colonialism as a threat by China and the Eastern Bloc.[28]

Representative Adam Clayton Powell Jr. (D-N.Y.) attended the conference, sponsored by Ebony and Jet magazines instead of the U.S. government.[28] Powell spoke at some length in favor of American foreign policy there which assisted the United States's standing with the Non-Aligned. When Powell returned to the United States, he urged President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Congress to oppose colonialism and pay attention to the priorities of emerging Third World nations.[29]

African American author Richard Wright attended the conference[30] with funding from the Congress for Cultural Freedom. Wright spent about three weeks in Indonesia, devoting a week to attending the conference and the rest of his time to interacting with Indonesian artists and intellectuals in preparation to write several articles and a book on his trip to Indonesia and attendance at the conference. Wright's essays on the trip appeared in several Congress for Cultural Freedom magazines, and his book on the trip was published as The Color Curtain: A Report on the Bandung Conference. Several of the artists and intellectuals with whom Wright interacted (including Mochtar Lubis, Asrul Sani, Sitor Situmorang and Beb Vuyk) continued discussing Wright's visit after he left Indonesia.[31][32][page needed] Wright extensively praised the conference.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bandung_Conference

==================

THEN CAME THE REVOLUTION IN INDONESIA.... SEE:

the CIA good fairy: the bad witch of the west...The CIA in Indonesia...

Background from the CIA World Fact Book:

The Dutch began to colonize Indonesia in the early 17th century; Japan occupied the islands from 1942 to 1945. Indonesia declared its independence shortly before Japan’s surrender, but it required four years of sometimes brutal fighting, intermittent negotiations, and UN mediation before the Netherlands agreed to transfer sovereignty in 1949. A period of sometimes unruly parliamentary democracy ended in 1957 when President SOEKARNO declared martial law and instituted “Guided Democracy.” After an abortive coup in 1965 by alleged communist sympathizers, SOEKARNO was gradually eased from power. From 1967 until 1998, President SUHARTO ruled Indonesia with his “New Order” government. After street protests toppled SUHARTO in 1998, free and fair legislative elections took place in 1999. Indonesia is now the world’s third most populous democracy, the world’s largest archipelagic state, and the world’s largest Muslim-majority nation. Current issues include: alleviating poverty, improving education, preventing terrorism, consolidating democracy after four decades of authoritarianism, implementing economic and financial reforms, stemming corruption, reforming the criminal justice system, addressing climate change, and controlling infectious diseases, particularly those of global and regional importance. In 2005, Indonesia reached a historic peace agreement with armed separatists in Aceh, which led to democratic elections in Aceh in December 2006. Indonesia continues to face low intensity armed resistance in Papua by the separatist Free Papua Movement.

=================

BEFOREHAND, WE SHOULD KNOW THE CHINESE HISTORY THAT IS INFLUENCING THE PRESENT:

Russia, Japan and the Chinese Empire

In the closing years of the nineteenth century, the Chinese Empire became one of the prized targets in the race to carve out spheres of influence and expand colonial empires. China had, in practice, long been closed to maritime foreign trade, which between 1757 and 1842 had been confined to Guangzhou. In that year the treaty of Nanjing (Nanking), signed after Great Britain had defeated China in the First Opium War (1839-42), had forced China to open five treaty ports to British ships and traders and to cede Hong Kong to Great Britain; the latter much to the dismay of Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston, who would have preferred to gain Zhoushan and not just a barren rock, as he said Hong Kong was, with almost nobody living there.

In 1844 France — simply as an imitation of the British, one French historian wrote — and the United States concluded similar treaties; the French succeeding in having China revoke a ban on Christianity.

Due to over-optimistic expectations about the prospects of trade with China too many ports had been opened at the same time, with the existing ones, Macau and Guangzhou, suffering from the new competition. Hong Kong and the treaty ports had a slow start, as did later ones. China was forced to make even more concessions in the Second Opium War (1856/7-60), fought by France and Great Britain together – with Great Britain initially somewhat weakened by the Mutiny in India, and having to redirect troops that were already assembled in Singapore to fight in China back to India.

These Chinese concessions appeared in the Treaties of Tianjin (Tientsin) concluded with Great Britain, France, the United States and Russia in June 1858. China was reluctant to comply but at the end of the war when British and French troops had entered Beijing the Chinese government was forced to ratify the Tianjin treaties in the Conventions of Beijing of October 1860.

China had to open an additional number of treaty ports and cede part of the Kowloon Peninsula opposite Hong Kong to Great Britain. Beijing also had to allow British, and thus also other foreign ships, to sail the Yangtze or Blue River flowing from Tibet in the west to Shanghai on the east coast, which would soon become a main artery for British commerce in China.

Along the Yangtze foreigners could trade at three river ports. Which ones these should be was still to be decided upon, but the provision was made that foreign merchant ships should not sail further inland than Hankou (Hankow). In the Convention concluded with France, China not only guaranteed the safety of Christian missionaries in China, but also committed itself to allowing them to settle in China wherever they wanted. Such a permission had not been mentioned in the French text of the treaty. It was only included in the Chinese text, inserted there by a French missionary acting as translator.

From then on, missionaries were allowed to live in the interior of China; a privilege denied to foreign traders, who, though allowed to travel in the country, had to take up residence in an increasing number of so-called treaty ports. France also used its position of power to have the cathedral in Beijing reopened. Soon Germany would join in. Germany’s interest in China dated from around 1860, when, in an effort to gain the same protection for its Asia trade that the British and French had, a Prussian naval expedition was dispatched to Asia under the command of Count Friedrich zu Eulenburg to enter into diplomatic relations with China, Japan and Thailand.

This resulted in treaties with Japan and China in 1861 and with Thailand in 1862. For years Germany would play a minor role in China, as would France. Great Britain’s greatest European rival in China became Russia, approaching China from the north.

During the Crimean War, Russia had still not been secure about its position along the upper north coast of the Pacific. A combined Anglo-French fleet had gone in search of Russian warships in the north Pacific and had tried to dislodge Russian stations along the Siberian coast; in doing so it hit at one of Russia’s weak spots, poorly defended by the Russian navy as the region was.

In 1854 there was a failed attempt to besiege the port of Petropavlovsk on the Kamchatka Peninsula, north of the Kuril Islands. The next year Great Britain and France tried again, only to find, as a British Member of Parliament would phrase it half a century later, ‘the forts dismantled, the [Russian] ships gone, and the inhabitants selling trophies of our defeat’. During the Second Opium War, coming so shortly after the Crimean War, Russia again did not preclude that Great Britain would use the occasion to undo some of the advances Russia had already made along the north Asian Pacific coast. This concern proved groundless.

In fact, Russia gained even more than the other powers. When British (and French) soldiers ‘in the most brutal manner were sacking the Summer Palace’, a British Member of Parliament would later observe, Russia, presenting itself as a friend of China and offering arms and advisers, was intently engaged in securing advantages by means of commercial treaties with the Chinese Empire.

If Great Britain, as a naval power, had to be content with Hong Kong, Russia, as a land power, gained a considerable slice of Chinese territory. In the 1858 Treaty of Aigun and the 1860 Convention of Beijing, China, weakened by having to fight the Second Opium War, ceded Outer Manchuria to Russia; that is, the territory on the left bank of the Amur River. China remained in control of Inner Manchuria, the land in between the right bank of the Amur and its tributary the Ussuri river. The Amur and Ussuri rivers, as well as the Songhua (Sungari) River, were opened to Russian ships, but not to vessels of other nations.

China and Russia agreed to exercise joint control over the land between the Ussuri River and the Sea of Japan. Another advantage the Russians gained was that its merchants were now allowed to trade in Ulan Bator in Mongolia and in Zhangjiakou (Kalgan) northwest of Beijing, a stipulation said to be included in recognition of the existing Russian trading route from Kiakhta (Kyakhta, Kiakta) on the Mongolian border to Beijing. In Ulan Bator, Russia was permitted to station a consul. Later, the Russian mercantile advance into Mongolia would become even more pronounced, as in the Ili or St Petersburg Treaty of 1881 China made additional trading concessions in Mongolia, similar to those Russia had been offered in Xinjiang.

By gaining Outer Manchuria Russia had finally gained a strong position along the Pacific coast, with Japan on the other side of the Sea of Japan. Russia had also become a neighbour of Korea, the ‘Hermit Kingdom’ as it was called at the end of the nineteenth century, a country even more xenophobic than China and Japan had ever been.

In 1860 Russia established the naval station Vladivostok – which had the disadvantage that it was icebound for four months of the year – thus adding a new dimension to naval relations in the Pacific. If Great Britain had been the main adversary of Russian expansion in Central Asia, then in the northeast it was Japan. Initially, in the decades after the opening up of Japan, Russia was still the strongest party.

The Treaty of Commerce, Navigation and Delimitation of 1855, also known as the Treaty of Shimoda, divided the Kuril Islands into Russian and Japanese portions, with Sakhalin, opposite the coast of Manchuria, coming under joint control. Twenty years later, in the 1875 Treaty of St Petersburg, Russia annexed Sakhalin, using what one author later called ‘coercive diplomacy’.

In return, Russia ceded its part of the Kuril Islands to Japan. For those in the closing decades of the nineteenth century, and apparently there were many, who saw behind every territorial expansion a strategic motive, the benefits of Sakhalin to Russia were clear. The island provided additional protection of the mouth of the Amur River, gave Russia control of the narrow northern entrance to the Sea of Japan, and might serve as a base of operation for an invasion of the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido.5 Initially, Japan’s politicians and military men depicted Russia as the aggressive enemy, the reason why the country needed its army and navy.

When Japan grew stronger both Russia and Japan began to aspire to a slice of Manchuria and control over or occupation of Korea. Korea could offer Russia the proverbial ice-free port along the Pacific coast it still lacked. First in mind were Wonsan (Gensan) and Port Lazareff at Broughton Bay on the northeast coast, initially also mentioned as the terminus of the Trans-Siberian Railway (in Russian terminology also the Great Siberian Railway, the construction of which had started in 1891 in Vladivostok when Nicholas II, then still crown prince, cut the first sod). Port Hamilton was another possibility before Great Britain occupied it in 1885 at the height of the Penjdeh Crisis. Busan (on the southeast coast) and other Korean ports could serve the purpose as well.

Strategically, there was much at stake according to contemporary evaluations. ‘Permanent Russian squadrons at Port Lazareff and Fusan’ would make Russia ‘the greatest naval Power in the Pacific’, Curzon wrote in 1896.

The first moves turning Russia and Japan into archrivals in north Asia were made in Korea, in those days still a Chinese vassal state, and which for decades, to use the description given by Curzon in the House of Commons in 1911, would be ‘one of the most unhappy of all nations in the world’ and ‘a sort of football kicked about by the Powers of the East’. Japanese efforts to gain control over Korea dated right back to the start of the Meiji Restoration. In 1868 a Japanese envoy had urged Korea in vain to acknowledge that the Japanese Emperor was of superior status to the Korean King.

The following year an invasion of Korea was contemplated for the first time, while in 1873 the decision by the Japanese government not to send a fleet to Korea to enforce upon it trade relations with Japan led to passionate protests among the military. Three years later, in 1876, Japan showed its military muscles for the first time by sending warships to the Han River. Where in 1871 the United States had failed Japan now succeeded. It forced Korea to open its first treaty ports, granting the Japanese extraterritorial rights there.

To embarrass China the first article of the Treaty of Kanghwa read that Korea, ‘being an independent state, enjoys the same sovereign rights as does Japan’. In 1879 Japan again moved against China and annexed Okinawa and the other Ryukyu islands in between Japan and Taiwan, which in the past had paid tribute to Japan as well as China. In Washington President Hayes said that the United States was prepared to mediate, but when Beijing turned to him to protest the annexation, he decided in favour of Japan.

In 1880 Japan gained access to the port of Wonsan opposite Port Lazareff. Wonsan was opened to other nations in 1883, the same year Chemulpo (Incheon), the harbour of Seoul on the west coast, also became a treaty port. Over time, as in China, the number of ports Korea had to open to foreign trade increased. The next to enforce concessions were the Americans with Commodore Shufeldt’s Treaty of Peace, Amity, Commerce, and Navigation of May 1882.

Included in the Treaty were the American promise to come to the assistance of Korea in case the country was attacked, and the Korean promise to open up the country to missionaries. Great Britain and Germany followed suit in 1883. Russia concluded its Treaty of Amity and Commerce with Korea in 1884. France did so in 1886. The following year, when Great Britain had decided to return Port Hamilton to Korea, London, more worried about the port becoming Russian than a Japanese advance in Korea, got China to vow that it would protect Korea’s territorial integrity. The competition over political influence in Korea between China, Russia and Japan could link up with domestic unrest, a struggle at court between rival factions, accompanied at times by outbursts of xenophobia.

One such instance took place in July 1882 when a mob attacked the Japanese legation and the Japanese ambassador and his staff had to flee to Chemulpo, where they took refuge on a British ship. The Japanese adviser to the Korean army was not that lucky. He was killed. Tokyo retaliated. It sent a naval squadron to Korea. Seoul turned to Beijing for help. Japan was still too weak for a military confrontation with China. In the Treaty of Chemulpo of August 1882 Korea had to assent to the stationing of Japanese troops on its soil for the protection of Japanese nationals. The presence of Japanese soldiers in Korea made for an explosive situation, domestically as well as internationally, the more so as China also established a military garrison near Seoul in 1882.

The next confrontation came in December 1884 when members of a pro-Japanese political group, the Korean Independence Party, backed by Japanese soldiers, occupied the Royal Palace. Three days later Chinese soldiers drove them away. Seoul became the scene of fierce rioting against the presence of Japanese and other foreigners in the country; inducing Tokyo to send additional troops to Korea. In 1885, when China was engaged in war with France, Japan moved again and a compromise was reached. In the Treaty of Tianjin of April of that year, also known as the Li (Hongzhang) -Ito (Hirobumi) Treaty, Tokyo forced China to withdraw its garrison from Seoul. Japan did the same. The Korean king, assisted by foreign advisers, should build up his own army. At Tianjin, China and Japan also agreed that in times of unrest in Korea both could send in troops, but only after they had informed the other of their intention. The moment to do so came a decade later.

In 1894 King Kojong (Gojong) turned to China for help to suppress a religiously inspired peasant revolt, the Tonghak rebellion, in southern Korea; a revolt partly inspired by xenophobic and anti-Japanese sentiments. China duly informed Japan that it was to send troops to Asan, along the south coast, near Seoul. Tokyo did not to object to this, but it did protest the reason presented by Beijing for its intervention. It could not accept the phrase that China acted ‘for the sake of a tributary State’. Japan also informed Beijing that the situation in Korea ‘seemed to be a very serious one’ and that it also intended to dispatch troops. The reason stated was to protect its diplomatic staff and other Japanese citizens in Korea, and, as the Japanese commander was to be instructed, if necessary also other foreigners and even the king of Korea.

China, clinging to its sovereign rights, impressed upon Tokyo that it should only land a small military force, one which sufficed for the protection of the Japanese, and that the Japanese soldiers should not march into the interior; demands turned down by Japan. Beijing, in turn, still considering Korea a Chinese tributary, rejected a Japanese proposal for a joint effort to reform Korea’s finances, civil service and army. Such reforms were necessary, the Japanese government would maintain, for domestic law and order and for the functioning of Korea as an independent state. In early June, after having sent an officer to Korea for an on-the-spot assessment, Tokyo decided that Japan had to go to war in order to maintain its position in Korea.

On 12 June the first Japanese soldiers disembarked at Chemulpo. In line with existing tradition they had strict orders that they had been sent to Korea for the protection of Japanese life and property only and should not engage Chinese troops in combat. In July Tokyo informed Beijing that it would regard the sending of additional Chinese troops to Korea as ‘a menace’. Another culprit in Japanese eyes was the Korean government, which, Tokyo maintained — ignoring the widespread anti-Japanese sentiments in Korea — tended to side with China because of ‘blind feelings of veneration which they, in their ignorance, cherished for China’. When the Korean government hesitated to side with Japan, the Japanese envoy in Korea, Keisuke Otori, ordered the Japanese troops to march to Seoul on 23 July. The Koreans should be shown that Japan was strong enough to guarantee the independence of their country and carry through the reforms which were needed in the country. In Seoul (only after they had been fired upon, the Japanese would claim) Japanese soldiers occupied the Royal Palace and confined the King to its premises. On the instigation of Keisuke Otori a pro-Japanese government was formed, which issued a declaration of independence and charged Keisuke Otori with the task of having the Chinese army withdraw its soldiers from Asan. China, in turn, decided to send fresh troops to Korea, claiming that the Japanese troops frightened the population and the Chinese traders living in Korea.

The Sino-Japanese War With war looming China turned to the powers to have Japan retreat from Korea. Great Britain, fearing the adverse consequences of war for its trade in China; and, as Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Grey put it, ‘the large moral grounds’ of maintaining peace, succeeded in having the powers give the ‘friendly advice’ to Tokyo and Beijing not to engage in war. It was in vain. On 1 August 1894, after Japanese and Chinese army and navy units had already clashed, Japan declared war on China. The stated issue was China’s ill-will with regard to Korea, a country which the Japanese declaration of war stated had been ‘first introduced in the family of nations by the advice and under the guidance of Japan’. Referring to the authority Keisuke Otori had been given, Japan and Korea concluded an agreement on 26 August, which would be in force for the duration of the war. The treaty stipulated that Japan would do the fighting in Korea, while Korea would provide the Japanese soldiers with ‘every possible facility … regarding their movements and supply of provisions’. That Japan won the war, and even more so the ease with which it did so, surprised many. The Japanese campaign was highly successful, also because already years earlier Japanese spies had mapped the battlefields. In September a Chinese fleet was defeated near the Korean-Manchurian border. As with so many acts of war, and both sides deploying modern warships, it gave military experts abroad an opportunity to see how modern war technology performed when put to the test.

In October troops landed on the Liaodong (Liaotung, Kwantung) Peninsula where Port Arthur, its fortifications and armament meeting contemporary, modern standards, was taken in November. More to the northeast, other troops had crossed the Yalu river, the border between Korea and Manchuria, while in February the Chinese naval base Wei-haiwei (Weihai) along the coast of the Shandong was seized, eliminating what was still left of the Chinese navy. Japan controlled the Bohai Sea, or as it was called in those days the Gulf of Pechili (Zhili, Chihli), and the Japanese troops might march on Beijing itself; but Tokyo abandoned any such plans, shrinking from the prospects of intervention by the European powers.

In desperation China again turned to the powers for help. In London Rosebery responded, once more appealing to a ‘concert of Europe’ (which domestically would earn him some scorn, because if anything seemed impossible in Europe it was to bring about such a concert). In October the British government suggested that the European powers and the United States should jointly guarantee the independence of Korea and ask Japan – not happy with the British initiative – to accept peace in return for a Chinese war indemnity. The initiative failed. Germany dismissed the plan as ‘scarcely opportune’, considering that the chance was slight that Tokyo would accept such a recommendation. Its refusal earned Berlin the praise from Japan for the ‘loyal German attitude’. An outright rejection also came from the United States. Washington, as Secretary of State Walter Quintin Gresham informed London, did ‘prefer to act alone’.

Only St Petersburg and Paris showed some interest. Russia, not wanting Japan to usurp Korea, made a definite answer dependent on the consent of the Tsar. France reacted in a similar non-committal way. On 17 April 1895, at the Treaty of Shimonoseki, China was forced to make a number of far-reaching concessions. One was that it had to recognise the independence of Korea and that, ‘in consequence, the payment of tribute and the performance of ceremonies and formalities by Korea in China, in derogation of such independence and autonomy’ should end.

Another was that China had to part ‘in perpetuity’ with Taiwan, the nearby Penghu Islands to the west of it, and the eastern part of the Liaodong Peninsula in South Manchuria. In addition, China had to open four additional treaty ports to foreign trade; an indication of Japan’s increasing commercial interest in Central China and a cause of lamentation to the British, a sentiment which would only become stronger over time. All four ports could be considered an encroachment on the British position in Central China. Two of them, Shashi in Hubei on the Yangtze and Chongqing (Chungking, Tchoung-king) in Sichuan where the Yangtze and the Jialing river met, were far inland. The other two, Suzhou (Suchow) and Hangzhou, were located in the Yangtze river delta. In Chongqing, according to some French businessmen the commercial capital of the rich province of Sichuan (Szechuan, Se-Tchouan), the Japanese saw to it that they got the best plot of land to build a concession.

They had also not forgotten to force China to accept that steamships – and not just sailing vessels – should be permitted to sail to the new treaty ports, thus allowing for a deeper and more intense economic penetration of China’s interior. Wei-hai-wei was to serve as a security for the war indemnity Japan had imposed. Tokyo promised that it would withdraw from Wei-hai-wei a year after China had paid the first two instalments. Japan’s victory gave Japan, and thus also the other powers, the right to build factories in treaty ports, changing the nature of Shanghai and other foreign enclaves and increasing still further the foreign economic onslaught on China.

The Japanese victory made a great impression worldwide; all the more so as such a devastating defeat of the Chinese forces had not been expected. It gave Japan, a British author would write a few years later, ‘a place among the nations that she could hardly have attained, and certainly not in the present generation, by any degree of cultivation of the arts of peace'. It also led to the first alarm among Europeans about their colonies in the Far East. In Indochina Governor-General Doumer worried in a report in 1897 about the danger Japan, with its recently acquired land hunger, might pose to the European colonies in Asia. A year later Curzon, soon to become Viceroy of India, observed that the ‘whole face of the East was changed by the results of that war. It exercised a most profound and disturbing effect upon the balance of power, and upon the position and destinies of all the Powers who either are situated or have interests around the China Seas’. Business circles were also alerted, but in a different way. A strong Japan was worrying, but a weak China meant new economic and political prospects.

The outcome of the war induced the Chamber of Commerce of Lyon to take the initiative for a ‘commercial exploration’ mission to south China. It left France amazingly quickly, in September, five months after the Treaty of Shimonoseki, and when it entered China was suspected of being the advance party of a French invasion army. There were to be more such missions, taking stock of opportunities and activities by rival nations – the Chamber of Commerce of Blackburn sent one in 1896 – culminating in Beresford’s tour in 1898, by which time domestic insecurity had become a main concern. The Liaodong Peninsula and its ice-free harbour, Port Arthur, commanded the entrance to the Bohai Sea. Its possession might give Japan control over a portion of China’s foreign trade, to the detriment of the commercial interests of other powers. Even more important was that the Bohai Sea was the gateway to Beijing. It was feared that the populous Zhili province and Beijing itself could come under Japanese control. It took an invading force twenty-four hours to sail from Port Arthur to the Dagu (Taku) Forts, which were built on both sides of the mouth of the Pei-ho River on the coast of the Bohai Sea. Once the forts had been taken an army could march inland; first to Tianjin with its foreign settlements and then to Beijing about eighty miles further inland.

However, as the Boxer Rebellion would show, such an expedition might not proceed as easily as contemporaries thought. At Shimonoseki Japan had demanded too much. The Liaodong Peninsula and Port Arthur were, as Taylor and other historians have observed, ‘the keys to Manchuria and indeed all of northern China’. Contemporaries were of the same opinion. Possession of Port Arthur, with its fortif ications built by German and British engineers and its British Armstrong and German Krupp artillery, would make Japan the ‘unrivalled master of North-China’. St Petersburg informed Tokyo that an occupation of Port Arthur was not only ‘a constant menace to the capital of China’, but would also ‘render illusory’ the independence of Korea, and thus would ‘jeopardise the permanent peace in the Far East’.

Russia, not yet having enough troops in the area to stop (even in a joint effort with China) a further Japanese advance, turned to Germany, Great Britain and France even before the treaty was signed. The aim was to deny Japan its newly acquired foothold on the mainland, which Russia was also vying for, the Liaodong Peninsula; a convenient stepping stone for Russia to Korea and for Japan to Manchuria. Germany, which less than a year before had rejected Rosebery’s peace effort, came out in support of Russia. For the British it was an unpleasant surprise. Besides strategic considerations, race also played a role in Berlin’s decision. Wilhelm II did all he could to warn the world of ‘the yellow peril’, die gelbe Gefahr.

On his instructions, and based on a sketch drawn by Wilhelm II, Hermann Knackfuss drafted the political cartoon Völker Europas, wahret eure heiligsten Güter! (‘Peoples of Europe, defend your most sacred possessions!’) depicting the danger Japan posed; with Germany in the shape of Archangel Michael – more often used by Wilhelm II as a symbol for the German empire – in the role of the valiant guardian of Europe. Copies were sent to European statesmen, to the Hamburg-Amerika Linie and the Norddeutscher Lloyd, and, to impress on him what was at stake, to Nicholas II. France, Russia’s partner in the recently concluded Dual Alliance, responded positively; though the idea of France acting in concert with Germany was not received well by sections of the French public. It would also earn France a ‘very visible hostility’ on the part of Japan (Doumer 1905: 383). At the time that St Petersburg sought the support of Berlin, Germany was seriously considering the establishment of a coaling station in China for its warships sailing in the region, which up to then had had to bunker in Nagasaki or Hong Kong.

During the Sino-Japanese War Wilhelm II had become convinced that London would use the war to take possession of Shanghai and ‘several other strategically important positions’ in China and that Russia and France would follow Great Britain’s example. In line with this, the Foreign Office had alerted the Imperial Navy Office to the possibility that other European powers might use the Sino-Japanese War to occupy parts of China, and that such an eventuality might provide Germany with the opportunity to acquire its own coaling station in China, by force or by negotiation. As late as March, Chancellor Prince Chlodwig Karl Viktor zu Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst had still advised against Germany joining Great Britain and Russia in mediating peace.

Showing himself quite satisfied with the profits that shipping and selling arms had brought German firms, he wrote to Wilhelm II that only Great Britain and Russia had to lose from a Japanese victory. Joining the two could only be to the detriment of Germany. Matters, however, would be different when there was some compensation, and Germany could ‘expect to acquire certain points on the coast of China’. Wilhelm II was not unfavourably inclined. In a letter to the Tsar he not only tried to convince Nicholas II that Russia’s role was crucial in defending ‘Europe from the inroads of the Great Yellow Race’, he also asked for Nicholas II’s help in Germany’s endeavour to ‘acquire a port somewhere where it does not “géne” you’.

In retrospect, the German Foreign Office would blame the navy for Germany not having a coaling station already. Naval officers tended to think big, turning the idea of a simple coaling station into a progressively more elaborate one; first a naval base, subsequently a point of support for trade, and finally even a nucleus of a colony. By doing so they only had delayed action. In April the Far Eastern Triple Alliance – or in German the ostasiatische Dreibund – of Russia, Germany and France, presenting itself as a guardian of China’s territorial integrity insisted that Japan should evacuate the peninsula.

The joint démarche took the form of ‘friendly advice’, which of course was not seen in this way in Japan; but, as the new Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Prince Aleksei Lobanov-Rostovsky, told the German ambassador, should Japan not comply then Russia would contemplate ‘joint warlike operations of the three Powers by sea against Japan, the first aim being to isolate the Japanese forces on the mainland’. The French and Russian envoys in Tokyo did not mention such a possibility when they protested about Japan holding on to Port Arthur. Only the German representative, a man of ‘violent character’ who ‘enjoyed the opportunity for humiliating Japan’, spoke of war.

Like Berlin, London had a surprise in store. Great Britain was also approached but had refused to join. The government of Rosebery, and indeed that of his successor Salisbury, valued good relations with Japan too much. One factor to consider was the challenges to the British fleet. Later Rosebery’s Foreign Secretary Kimberley explained that ‘looking at the great change impending in the Far East, … there was nothing more important to this country than to establish a friendly relation with the growing naval Power of Japan’.

In view of the fact that the British commercial presence in China could only be shielded against the malintent of others by naval protection, he, not without reason, added that a naval power would ‘always be of more consequence as a friend to this country in that quarter of the world than any other Power’.24 Yet Great Britain did not emerge unscathed. In Russia and Japan its position met with hostility.

The reaction in the Russian press made Queen Victoria complain to Tsar Nicholas II about the ‘most violent and offensive articles against England’ (Carter 2010: 179). In Japan, where the British effort in October to mediate peace had already not been taken kindly, resentment had only grown because London had failed to come to the assistance of Japan in dealing with the Far Eastern Triple Alliance; thus, being indirectly co-responsible for a political defeat that was, and would continue to be, considered a great humiliation in Japan.

In retrospect, some British politicians even spoke about ‘Rosebery’s mistake’. In their view, London had ‘abandoned Japan to Franco-Russian coercion’. Another country that stayed aloof, but for different reasons, was the United States. It had other worries. Fearing a partition of China and the harm this would do to American contemporary and (especially) future commercial interests in China, Washington had already urged Tokyo to show restraint during the war.

It hoped that a grateful China would grant concessions to American companies, first and foremost in Korea. Gresham impressed upon the Japanese ambassador that if Japan continued ‘to knock China to pieces, the powers, England, France, Germany and Russia, under the guise of preserving order’ would partition China. Washington’s refusal to side with the Far Eastern Triple Alliance was one of the first indications of a growing rift between the United States and Russia, ending ‘a century of friendship’.

The combined pressure of Russia, France and Germany was too much for Japan. As early as May, in an Imperial message, Tokyo pointed out that Japan had ‘taken up arms against China for no other reason than our desire to secure for the Orient an enduring peace’. Japan would follow the ‘friendly recommendation of the three Powers [which] was equally prompted by the same desire’. Face was saved. By signing the Treaty of Shimonoseki, China had ‘shown her sincerity in regret for the violation of her engagements’, which meant that the justice of the Japanese cause had ‘been proclaimed to the world’.26 The price was still more war reparations. In November Japanese troops withdrew from the Liaodong Peninsula. The retreating troops took along artillery, machinery and everything else worth taking and demolished everything else that could not be transported back to Japan.

Abandoning Liaodong greatly upset the Japanese. As Drea (2009: 90) wrote, it created a ‘sense of national humiliation’ and ‘a determination, encouraged by the government, to avenge this wrong’, aimed in the first place at Russia. Japan could keep Taiwan, where it was almost immediately confronted with a rebellious local population resisting Japanese rule (as they had done to Chinese rule before), lasting at least until 1907, which for the moment put a stop to any Japanese plans to turn the island into a colony for its surplus population. Nevertheless, Taiwan, which had also figured in earlier German and French plans and in Perry’s plan for a naval base, was a valuable prize.

The Taiwan Strait was a busy shipping lane, vital to China trade. The island itself formed a bridgehead to China. It could serve as a base for economic expansion and, if needed, a military incursion into the opposite Chinese province of Fujian (Fukien), of which it had been part of in the past. Abroad, Taiwan also soon came to figure in scenarios about a Japanese expansion southwards, towards the Philippines, and after that – the Dutch feared – towards the Netherlands Indies. Even in faraway Australia people began to worry about such a move and the prospect of a Japanese invasion.

Almost immediately, after Japan had evacuated Liaodong, speculation arose about Russia itself occupying Port Arthur. Responding to such suppositions, A.J. Balfour, First Lord of the Treasury, true to the spirit of free trade, suggested in February 1896 that Russia should be allowed to acquire an ice-free commercial port on the Pacific north coast.

To explain his remark, which was not well understood in Great Britain, he pointed out that such a Russian port could only benefit British commerce; taking the position that the more Chinese ports were opened (and the more railways built) the better it would be for international trade and thus also for Great Britain. China was hardly capable of paying the indemnity Japan had forced upon it. The loans Beijing had to arrange to raise the money gave rise to national and international complications. Nationally, on top of the usual financial consequences of war for a population came the new obligation of the indemnity, burdening the people even more, with all the feelings of discontent that this would entail. China, almost broke, also had to redirect the appropriation of the tax proceeds.

Such money could no longer be used for the upkeep or improvement of local security. Beresford identifies this as one of the reasons why local Chinese officials and the Chinese army could not guarantee law and order in the country, so desperately needed by foreign traders and investors at that time. The troops needed for this also had to be deployed to guard the coast of the Bohai Sea against a foreign invasion. Beresford also notes that the impression the Chinese people had gained, that they were no longer paying taxes for the good of the country or their province, but that the money went to foreigners, ‘kindled the latent hostile feeling’ against people from abroad.

Internationally, the competition and animosity between the powers was augmented by the question of which power was to arrange the loan (and thus could expect something in return) and which banks would put up the money; resulting, among other things, in additional complications in the Anglo-French negotiations over Thailand. Initially, London had suggested that Great Britain, Germany, Russia and France should jointly arrange the first loan to China. However, due to Russian manoeuvring, and in spite of Great Britain urging Beijing not to accept such an offer, the loan provided in 1895 was a Russo-French one, with Tsar Nicholas II complaining about the delay the ‘intriguing of the British and Germans’ in Beijing had caused. For this purpose, the Russian Ministry of Finance in December 1895 established the Russo-Chinese Bank, which would play a crucial role in Russia’s advance in northeast China. The outcome also added to American frustrations about Russian policy in the Far East. An American company had also been interested in the loan and its failure to subscribe was attributed to Russian scheming.

In 1896, when China again needed foreign money to finance its indemnity payments to Japan, it again approached the French government. France was given the right to construct a railway from Tonkin to Lungchow in Guangxi, but the loan was provided by the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank and the Deutsch-Asiatische Bank. In January 1898 Beijing, not happy with the conditions St Petersburg wanted to attach to a new Russian loan, turned to London to guarantee a third loan to pay the final instalment of the reparations. London had already protested in Beijing against one of the Russian conditions, the replacement of Hart as inspector general of the Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs Service.27 The Chinese request was received well in British financial circles, but Salisbury himself had ‘the greatest hesitation’.

He did not look forward to the task of ‘finding money for Governments that might want money’.28 Nevertheless, and to the displeasure of Russia and France, the British government was prepared to arrange the loan. In return, London initially asked, among other concessions, that Dalianwan (Talienwan), the bay on the east side on the Liaodong Peninsula, and Nanning in Guangxi on the West River in the south should become open ports. This was not a smart move, and could only rub up Russia and France the wrong way, who had set their sights on Dalianwan and Nanning, respectively. Both powers protested.

Beijing, fearing additional bullying by St Petersburg and Paris, could not meet the British conditions. A day after the Chinese had indicated on 16 January that the opening up of Dalianwan ‘would embarrass them very much’, the British envoy in Beijing was instructed by telegraph not to insist. London did so, Salisbury said, with reluctance.

Nevertheless, on 19 January the British government was still made to understand by Russia that a demand to turn Dalianwan into an open port ‘could not be regarded as a friendly action’. Salisbury suggested that the matter be left alone until a railway had reached the port. He defended his decision by pointing out that the hinterland of Dalianwan was ‘practically worthless in itself, and that no trade could arise there until the railway reaches the port’. Salisbury kept silent about Nanning, which remained equally closed. An Anglo-German loan, again by the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank and the Deutsch-Asiatische Bank (and not an exclusively British one, which both Russia and France had protested against), was issued in March 1898.

Russo-Japanese strife over Korea After the Sino-Japanese War the struggle for control over Korea became one between Russia and Japan; China being too weak to enforce any claims. Korea had the misfortune of being the terminus of the Russian advance in north Asia, while a Japanese occupation of the country would threaten Russia’s move into Manchuria. Having practically no army and navy itself, Korea became, in the words of Hamilton, ‘the helpless, hapless sport of Japanese caprice and Russian lust’.

Having few investments in Korea, Russia’s intentions were primarily strategic. Economically far outshone by Japan, Russia presented itself as the champion of Korean national integrity. Japan, in justifying its policy, stressed its dominance in trade with and investments in Korea and the many Japanese who had settled there. Indeed, Japanese trade far exceeded that of other nations; Russian trade coming second, but only at a far distance.

In 1902 almost 299 Japanese steamers, with a total tonnage of 186,050 tons, entered Chemulpo, the main port of Korea, compared to only 42 Russian with a total tonnage of 58,332 tons (and only three from Great Britain, one from Germany and the United States each, and none from France). In the same year both Japanese and Russian liners called at Korean ports. Those from Russia, plying between Vladivostok and Shanghai, would call in at Busan and Wonsan.

Curzon suspected that the venture was far from profitable and that the main reason to set up the Russian line in 1891 had been political. To him it was yet another example of how Russia made ‘an experimental and even expensive commerce subserve larger political ends’. He was sure that (as other powers did) Russia was preparing for the deployment of auxiliary warships in war; that merchantmen and ocean liners could be transformed into warships when the moment was there. The real reason behind the Russian line was ‘the avowed object of providing a useful auxiliary marine, with well-organised complement, in time of war’.

Japan, in the aggressive tradition it had already established, continued to try to gain direct political control. On the instigation of the recently appointed Japanese ambassador, Miura Goro, Korean and Japanese assassins forced their way into the Palace in October 1895. They murdered Queen Min Myongsong, who, contemporary observers agreed, held more power than her husband and was seen as the main obstacle to growing Japanese influence in Korea. King Kojong, an American journalist wrote a decade later, ‘never recovered from the shock caused by the murder of his wife’ and was in ‘constant fear’ of being assassinated himself.

Miura denied any Japanese involvement, but after foreign protests was recalled by Tokyo, where Prime Minister Ito Hirobumi claimed that Miura had acted on his own. Kojong turned to Russia for help. On 10 February 1896 between 100 and 150 Russian sailors landed at Chemulpo and marched to Seoul. The following day the king escaped from his palace and took refuge in the Russian embassy. In May the Russian and Japanese envoys in Seoul came to an agreement over his safety. This was followed in June by an agreement on the independence of Korea between the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Lobanov-Rostovsky, and general Yamagata Aritomo, the Japanese Minister of War and Inspector General of the Japanese army, who was in Russia for the coronation ceremony of Tsar Nicholas II.

Lobanov-Rostovsky rejected Yamagata’s offer to institute a Russian sphere of influence in the north of Korea and a Japanese one in the south. It took until February 1897 before Kojong could return to his Palace and a few months later, in August, almost two years after the Treaty of Shimonoseki, he officially proclaimed the Empire of Korea and assumed the title of Emperor. Part of the June 1896 agreement was that Lobanov-Rostovsky consented to Japanese troops guarding the telegraph line between Busan and Seoul and Japanese settlements in Seoul, Busan and Wonsan. From his side, Yamagata did not object to Russian troops protecting the Russian embassy and the Russian consulates. The sending of additional troops became subject to prior consultation.

Russia continued to try to expand its military and economic influence in Korea. On the explicit request of Kojong, St Petersburg stressed, it sent military instructors to Korea in 1897. Russia also tried to remove the one important asset the British had in Korea: John McLeavy Brown, who had come to the country in 1893 when Hart had tasked him with running the Korean customs. In 1894 McLeavy Brown was appointed head of the Imperial Korean Maritime Customs, newly instituted on the instigation of Japan. He was one of the most influential foreigners in Korea. McLeavy Brown had a hand in the modernisation of the city of Seoul, and besides running the customs service he also became financial adviser to the Korean government in 1893; an unhappy task as Kojong was not known for his thrift.

The British held McLeavy Brown in high esteem. He was ‘the man who has held the Korean State together’, Hamilton wrote. Russia and its ally France detested the key positions held in the Chinese and Korean customs service by Hart and McLeavy Brown. To the Russians, McLeavy Brown was the man who could thwart their economic and political schemes in Korea. At the end of 1897 the Russian Consul General, Alexis de Speyer, acting in concert with the French envoy, tried to get rid of him. They partly succeeded. McLeavy Brown lost his position as financial adviser but remained Head of Customs, where a Russian official was appointed alongside him. Such Russian intrigues convinced Salisbury that Russia was set on occupying Korea, and that any protest in St Petersburg would be a futile action.

British commercial interests in Korea were, in the words of Curzon, ‘not assessable at a very high figure’ and initially the British remained on the sidelines, only acting when the safety of British nationals was at stake or prestige had to be upheld.32 In July 1894 British troops had landed in Korea after the British Consul General, Walter Hillier, had been beaten up by Japanese soldiers; after his wife had protested ‘vehemently’, the same soldiers had ‘scattered the chair bearers and pushed the chair, with Mrs. Hillier in it, into a ditch’. In October 1895, during the turmoil in Seoul, British troops once again landed in Korea, this time in Chemulpo. The following year, in response to the Russian troop movement in February, and at the request of the British Consul General, British marines entered Korean territory for the third time; officially to protect the British legation.

In 1897 Great Britain again decided to act. In July Curzon, in his capacity as Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, had already made clear the British position that ‘Corean territory and Corean harbours’ should not be ‘made the base of schemes for territorial or political aggrandisement, so as to disturb the balance of power in the Far East and give to any one Power a maritime supremacy in the Eastern seas’.33 When, in December 1897, news reached London that a Russian squadron of nine warships had sailed to Chemulpo to bully Korea into allowing a Russian coaling station at Deer Island off Busan, the British Admiralty ordered the Commander of the China Station, Admiral Sir Alexander Buller, to have a British fleet of about the same strength sail to Chemulpo.

The show of force had the desired result. Russia was forced to back down, while as a side effect the position of McLeavy Brown as head of the Korean maritime customs was secured. In a more general sense, the Russian adventure in Korea was also not a great success. Early 1898 was a time of intense anti-Russian demonstrations and protests in Seoul against the influence and concessions foreigners had gained. St Petersburg, as it revealed in March, felt compelled to complain to the Korean government about the xenophobic circumstances under which the military officers and the Russian Head of Customs had to work. Referring also to ‘parties’ in Korea which publicly vented the opinion that the country could well do without foreign assistance, Kojong and the Korean government were asked whether the services of these persons and the ‘protection of the Court’ were still needed. The answer was: many thanks, but no we do not need them anymore. Consequently, the Russian Head of Customs went home. The Russian officers were discharged from the Korean army, but stayed in Korea. In view of the tense domestic situation, they were attached to the Russian embassy.

Next, the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Baron Roman Romanovich Rosen, and his Japanese colleague, Baron Nishi Tokujiro, met in Japan to try to hammer out a division of Japan’s and Russia’s spheres of influence in northeast Asia. Instead, in Tokyo the Nishi-Rosen Protocol was signed on 25 April 1898. In it Japan and Russia ‘definitely’ recognised Korea’s independence.34 They also promised not to interfere in Korean domestic affairs and not to send military or financial advisers to Korea without consulting each other first. Russia refused to give Japan a free hand in Korea in return for its own preponderance in Manchuria.

What the Russians had to admit was that economically Japan had a far greater presence in Korea and that much more Japanese than Russians had taken up residence there. Hence, the Protocol mentioned that Russia would not ‘impede the development of commercial and industrial relations between Japan and Korea’.

Satisfied, Balfour, the British First Lord of the Treasury, spoke in the House of Commons of Russia’s ‘great retreat in Korea’.36 Russia also failed to get a coaling station on Korean soil. In fact, it was not such a disaster for Russia, having just leased nearby Port Arthur from China in March; though the navy’s preference was for a base in Wonsan Korea...

https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/315/oa_monograph/chapter/2370661

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.