Search

Recent comments

- hit?....

5 min 12 sec ago - cooperation....

3 hours 11 min ago - leave....

21 hours 1 min ago - costly....

21 hours 54 min ago - stormtroopers....

23 hours 11 min ago - friend-ships.....

1 day 1 hour ago - the lobby....

1 day 2 hours ago - not worth...

1 day 3 hours ago - illegal stuff....

1 day 4 hours ago - no shipping.....

1 day 14 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

meanwhile in argentina: beware mob miracles....

In the 1990s, Argentina was often cited as an example of an “economic miracle” and Russia was advised to take the same economic measures as Buenos Aires: closely follow all the recommendations of the International Monetary Fund, remove trade barriers, sell key sectors of the economy to Western investors, eliminate the social sector, and make the dollar the official currency instead of the “rigid” ruble.

A quarter of a century later, it has turned out that Argentina was indeed a good example… of the kind of fate Russia managed to avoid.

International monetary fraudThe International Monetary Fund (IMF) has a bad reputation. Many believe that instead of providing real solutions to economic problems faced by the countries that seek its help, the IMF “finishes them off,” totally depriving these countries of financial independence.

This is partially true. In fact, countries that are well off don’t turn to the IMF – the organization is usually a last resort for nations facing an economic crisis, even though the funds provided by it are not enough for the countries in need. The IMF was once compared to a microfinance organization, as both turn financially illiterate and desperate people into victims of loan bondage.

A more appropriate image, however, would be to compare the IMF with a classic example of a “kulak”[literally “fist”: a rich peasant in 19th-20th century Russia]. After the abolition of serfdom in Russia in the 19th century, the kulaks not only supplied the poor peasant population with affordable goods, loans, and booze, but made the locals completely dependent on their services. Once someone turned to the kulak, they could never get rid of him. Unable to pay back the loan, the peasant would quickly lose his deposit – his working tools, cattle, or farm. Meanwhile, without the kulak, who hired workers, the peasants and their families had no employment and would starve to death. At the end of the day, the peasants would go to a local pub – owned by the same kulak – where they would spend their last pennies on drinking themselves into oblivion.

It may look like the IMF operates quite differently – after all, as a non-commercial organization, it does not directly earn money and positions itself as a kind of mutual assistance fund designed to help “facilitate international trade,” to “address the balance of payments imbalances,” and even to “generate confidence” among member countries.

The provision of loans by the IMF, however, is accompanied by a number of conditions. Formally, these are supposed to serve good purposes– ensure economic stabilization, balance the budget, fight inflation, and ultimately, help return IMF funds and ensure stable economic growth.

In reality, the borrower state loses financial independence not only for the time being, until it repays the loan, but for a long time afterwards – sometimes forever. As a result of the reforms, the country is left without the industrial sector, with government spending cut to a minimum, state property sold off, and an open market. The country becomes dependent on international (in other words, US-controlled) financial flows and finds itself in the position of a farm worker whose tools for working the land have been snatched from him, and who cannot provide for himself even after paying off the loan. This forces one to go into eternal slavery, spending the little that one has left after paying off the loans in the “pub,” that is– on imports continuously supplied by multinational corporations.

Of course, it’s not just the IMF, with its principle of “push the falling one,” that is solely responsible for such an outcome. The country’s economic authorities – the ones that have brought it to such a point – rarely demonstrate financial literacy after turning to the IMF. Their actions often aggravate the problem, and they deserve no pity. However, IMF regulations deprive the country of protection, allowing financial sharks from all over the world to devour the weakened economy and buy up assets at a fraction of the price, which leaves the nation completely devastated.

How did things reach such a point?Argentina, or the “country of silver,” was marked by economic turbulence throughout the second half of the 20th century. Decades of incompetent financial policy, abrupt switches from socialism to ultra-liberalism, failed monetary reforms, and foreign loans that were swallowed up by the social sector, were further aggravated by the unsuccessful rule of a military junta and the lost Falklands/Malvinas War. By the early 1990s, Argentina had an annual inflation of 2000-3000% (12,000% per annum at its highest), with a huge public debt and a giant hole in the budget amounting to 16% of its GDP.

In the same years, Russia faced even bigger problems. In 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed and turmoil reigned in the newly independent Russian Federation. The country was shaken by riots and strikes, and crime thrived. At the same time, war broke out in the Caucasus and a permanent political crisis raged in Moscow, which resulted in a short-but-bloody conflict in 1993.

Economic ties and supply chains between the former USSR republics collapsed, and the industrial sector practically stopped operating. To make things worse, the planned economic system also collapsed, and Soviet enterprises were like kittens thrown into the waters of a new market. The country was not merely bankrupt – there was virtually no budget, no taxes, no financial control. The nation was in a state of nearly absolute economic anarchy. The new Russian authorities had no idea how to get out of the crisis and, so, just like in Argentina, they resorted to the printing press. As a result, in 1992, inflation in Russia reached 2500%.

Shock therapyThe era of the “economic miracle” in Argentina started in 1991, when Domingo Cavallo became Economy Minister. In order to obtain IMF loans, he took unprecedented measures. In a short time, almost all state property was privatized (including “national riches” such as the banking sector, railways, the mining and heavy manufacturing industries). Another monetary reform was carried out – first, the peso exchange rate was rigidly pegged to the dollar and, then, the US currency was legalized for use within the country. In the first years, the result was impressive: foreign investments poured into Argentina and its economy grew at double-digit rates. Despite the sharp reduction in social budget expenditures, unemployment remained at an acceptable level, the country’s citizens received a respite from hyperinflation and were given access to cheap loans – they were finally able to breathe a sigh of relief and eat their fill.

Privatization had a beneficial impact on corporations that used to drown in bureaucracy – for example, people would wait for years to get a telephone line connected when the service was provided by state companies but, after privatization, such issues were resolved in a week.

Argentina was considered an ‘exemplary student’ – despite the fact that its economy collapsed, the country followed the right advice and went on to thrive.

Meanwhile, Russia tried to follow its own path. Western financial advisers, nicknamed the “Chicago boys" flocked to Moscow and tried to persuade the Russian authorities to allow Western investors to take part in the privatization process. However, even though the Kremlin made many controversial economic decisions in the early 1990s, it would not agree to their proposals. Strategic industries (ie, the military-industrial complex, railway transport, and the energy, gas, nuclear and space industries) remained in state ownership, while other enterprises were distributed into private hands virtually for free – either through vouchers or loans-for-shares auctions. This is how a class of national oligarchs appeared, while the share of foreign capital in the privatization process turned out to be insignificant.

In other matters, then-Acting Prime Minister of Russia Yegor Gaidar and his cabinet acted in accordance with classic IMF principles: removing trade barriers, lifting price controls, cutting social services and budget costs, and keeping the ruble exchange rate relative to the dollar for the convenience of foreign investors.

To maintain the exchange rate and fill the budget, the government issued so-called short-term government bonds (GKO). In reality, it was a financial pyramid scheme, where debts on previous bonds were covered by new loans. The country had no money and there were no foreign investments in the real sector, so apart from IMF loans, the bonds were the only solution to make ends meet.

The fall of the house of UsherThe “Argentine miracle” came to an end in 2001. Due to the Asian financial crisis, national exports started to decline but the government was unable to devalue the currency and increase export earnings, since the peso remained rigidly pegged to the dollar. The largest banks and nearly all profitable enterprises were controlled by foreign capital, and investors began to withdraw funds from the sinking country. The growing holes in the budget were plugged with new loans and, finally, on December 23, 2001, Argentina declared the largest default in world history ($82 billion).

In Russia, the GKO pyramid collapsed in August 1998, and so did Acting-PM Gaidar’s economic model, built on IMF principles. It was then that our paths with Argentina diverged – the Russian government devalued the ruble, new life was breathed into the industrial sector, foreign and domestic investments started flowing in, and export was renewed. New banks emerged from under the wreckage of the old institutions that collapsed along with the GKO system, and today these banks form the basis of the national financial system.

In the 2000s, under President Putin, the Russian government consistently strengthened its financial independence, carried out tax reforms, took control of the oligarchs (they had to either work for the country, or were deprived of their property). And, although this process was facilitated by high oil prices (Russia's main export commodity), the success of Putin's reforms would have been impossible if, like Argentina, we had sold the country to foreign investors.

To Jupiter and beyondHaving survived two more defaults since 2001, shifted from the left to the right side of the political spectrum and back, in 2023 Argentina entered a new economic crisis. Libertarian Javier Milei, who was elected president a few days ago, promised to fix everything by reviving Cavallo's reforms: abolishing half of the government and the country’s central bank, abandoning the national currency in favor of the dollar, radically reducing taxes and government spending. Will this work? Time will tell, but there is no reason to expect that the result will be any different from what happened in 2001.

And what about Russia? Last year, we faced the strongest sanctions in world history – and withstood the trial. The strength of our economy surprised not only the West, but also many people in Russia. The economic blockade and the flight of foreign capital did not lead to economic collapse – the players that left the market were promptly replaced by others (often domestic companies) while Russia’s financial system demonstrated impressive independence and compliance with world standards. Having slightly declined last year, in 2023 the Russian economy showed steady growth which exceeded the economic growth of those countries that imposed sanctions against us.

All this became possible because back in the 1990s, we did not buy into the ‘sweet’ promises of the West and did not accept the yoke of slavery like Argentina did, but instead chose to follow an arduous but free path.

https://www.rt.com/news/587925-economic-policy-argentina-russia/

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW..............

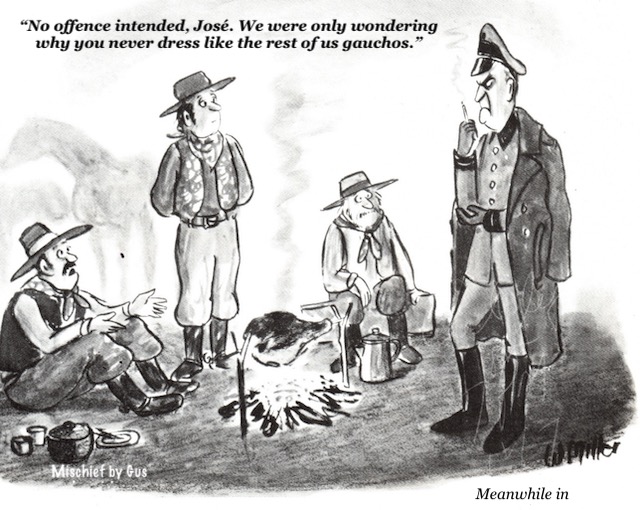

Cartoon at top c. 1960, the New Yorker.....

- By Gus Leonisky at 27 Nov 2023 - 8:35am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

a fascist.....

Pinochet wannabe? Argentina’s president-elect is not the libertarian he claims to be

Javier Milei says he is a freedom-loving anarcho-capitalist, but scratch him and a fascist bleeds through...

BY Bradley BlankenshipThe far-right Argentine economist and so-called “libertarian” Javier Milei was elected president on Sunday night, promising to tackle inflation and take a sledgehammer to the state in the midst of an economic crisis. But his proposed policies will most likely not be a panacea for Argentina’s woes and, more likely, will only harm the country more.

Before detailing Milei’s particular positions, it needs to be noted upfront that Buenos Aires’ economic crisis is directly attributed to former right-wing President Mauricio Macri (2015-2019), who took out a massive International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan in hopes of boosting his political cred before a tough reelection that he eventually lost. It was this massive and unpayable debt that carried on into the administration of current outgoing President Alberto Fernandez, contributing to hyperinflation. The history of Argentine economics is long and complicated (the economy is in crisis about every six years), but this latest one is directly attributed to the same sort of austerity and Western bootlicking that’s on the table today.

That’s where Javier Milei comes in. He wants to lean into these very same policies and institutions that mangled the Argentine economy, namely the IMF and the West, predominantly the United States, while also giving up his nation’s sovereignty by adopting the US dollar. He wants to cut off ties with major countries like China purely on ideological grounds, never mind how ridiculously this would destroy Argentina’s supply chains and place in international trade. He has also promised to abandon the BRICS format, opting instead to do business with the “civilized” world – North America, Europe, and their partners, including Israel.

It’s clear that this is not only foolhardy, given the long-term trajectory of the eastward drift of economic, political, and diplomatic power, but an outright betrayal against the Argentine people. Abandoning its sovereign currency – just like Ecuador and El Salvador, both countries themselves undergoing regular cycles of turmoil, did – would guarantee that Buenos Aires’ monetary policy is written in Washington, DC. Without fiscal exchange and labor market integration, this effectively would make Argentina a US colony.

READ MORE: https://www.rt.com/news/587742-argentina-milei-pinochet-president/

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW..............

rattenlinien....

The ratlines (German: Rattenlinien) were systems of escape routes for German Nazis and other fascists fleeing Europe from 1945 onwards in the aftermath of World War II. These escape routes mainly led toward havens in Latin America, particularly in Argentina, though also in Paraguay, Colombia,[1] Brazil, Uruguay, Mexico, Chile, Peru, Guatemala, Ecuador, and Bolivia, as well as the United States, Canada, Australia, Spain, and Switzerland.

There were two primary routes: the first went from Germany to Spain, then Argentina; the second from Germany to Rome, then Genoa, then South America. The two routes developed independently but eventually came together.[2] The ratlines were supported by clergy of the Catholic Church.[3][4][5][page needed]Starting in 1947, some U.S. Intelligence officers utilized existing ratlines to move certain Nazi strategists and scientists.[6]

While reputable scholars unanimously consider Nazi leader Adolf Hitler to have died by suicide in Berlin on 30 April 1945, various conspiracy theories claim that he survived the war and fled to Argentina.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ratlines_(World_War_II)#

------------------------------------

BY ELDAR MAMEDOV

The shock election of a self-proclaimed “libertarian liberal," the chainsaw-wielding eccentric Javier Milei as Argentina’s president has attracted a flurry of attention globally.

Most of it was focused on the radicalism of Milei’s economic proposals to cure Argentina’s chronic ills — chief among them an annual inflation at the rate of 143% and the poverty that has engulfed over 40% of Argentines, and all that with an outstanding debt of $43 billion owed to the International Monetary Fund.

Milei’s remedies include liquidating Argentina’s central bank, dropping the national currency — the peso — in favor of the U.S. dollar, privatizing state assets and slashing public expenditures, including subsidies for the most vulnerable individuals and communities. The chainsaw that he adopted as his icon during the election campaign symbolized his intention to demolish the state, which, according to Milei, is at the root of Argentina’s relative decline in the 20th and 21st centuries.

While some libertarians, notably in the U.S., welcomed his election as the latest and best chance to advance their long-cherished beliefs and a future inspiration for the U.S., their enthusiasm may be misplaced. Milei’s main focus may be on the economy, but, as president, he’ll also have to steer Argentina’s foreign policy.

This is not an area in which he has displayed much interest or knowledge to date, but someone like Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.), a standard bearer of libertarianism in the U.S., would hardly recognize himself in the positions embraced by Milei. In fact, Milei’s foreign policy views, to the extent they exist, are far closer to neoconservative than libertarian. His views would easily find home in hawkish Washington D.C. think tanks and parts of the mainstream of both the Republican and Democratic parties.

This is not to be underestimated, as Argentina is a member of the G-20, the third largest economy in Latin America, and has recently been invited to join BRICS, a grouping that comprises China, Russia, India, Brazil and South Africa.

Milei’s foreign policy views, as expressed repeatedly during the election campaign, are starkly Manichean — they divide the world into democracies and “communist autocracies.” Counter-intuitively for a self-proclaimed champion of free trade, he promised to sever ties with two of Argentina’s main trade partners — China and Brazil (combined, both account for around 25% of the total of Argentinian exports) — on the grounds that both are ruled by “communists.” China was an object of particular scorn, with Milei dubbing the country at one point “an assassin."

Milei is a staunch supporter of Ukraine, in contrast to a more moderate position espoused by the outgoing center-left Peronist administration which, while condemning Russia’s aggression of Ukraine, was also reluctant to sever ties with Moscow, which grew closer during the pandemic when Argentina acquired Russian vaccines, with results generally deemed acceptable.

Perhaps on no issue Milei’s neoconservative credentials are more on display than in his fervid embrace of Israel. While Argentina, under different governments, has generally enjoyed good relations with Israel, those were traditionally balanced by Buenos Aires’ engagement with Arab countries and, at times, even Iran. That balancing act did not prevent Argentina from declaring Hezbollah a terrorist organization for its alleged role in the notorious 1994 bombing of a Jewish community center in Buenos Aires.

Milei’s defeated opponent, Sergio Massa, promised to similarly add Palestinian Hamas to Argentina’s terrorist list if he had been elected. Milei, however, wants to go much further. He declared that his first international trips as president-elect will be to Israel and the U.S. He also promised to move Argentina’s embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. Such a one-sided reorientation would represent a major break in Argentina’s traditional foreign policy consensus.

Milei is also opposed, on ideological grounds, to Argentina joining the BRICS, despite the invitation issued by the existing members, reportedly the result of heavy lobbying by Brazil on Buenos Aires’ behalf. While the prospect of joining the group that represents more than 40% of the world’s population and 31% of global GDP (and also a destiny of some 30% of total Argentine exports) is seen as an opportunity by many Argentine businesspeople and politicians, for Milei BRICS represents little more than a dictators’ club.

The president-elect is also remarkably skeptical about Mercosur, a South American trade bloc which includes, besides Argentina, also Brazil, Uruguay and Paraguay. Milei dismissed it as merely a “low-quality customs union that distorts commerce.” Such a position raises fresh questions about the prospects for a long-delayed trade deal between Mercosur and the European Union.

There is always a chance that the realities of governing (among them, the fact that his party holds relatively few seats in the National Congress) would temper some of the most radical ideas Milei spouted during an election campaign. After all, the former president of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, with whom Milei professes a mutual admiration also started as a fierce critic of China, only to significantly soften his position while in office.

But during the presidential debate, Milei displayed a worrying ignorance of how international relations work. While no longer calling for a complete severance of ties with China and Brazil, he insisted that any such interaction should be left entirely to the private sector, apparently oblivious to the fact that it is governments that negotiate international trade frameworks and agreements, including tariffs, phyto-sanitary rules, and other measures.

That is especially true in the case of China, where the weight of the public sector in the country’s external economic activity is preponderant. Currently, alongside many smaller projects, China is involved in building two hydroelectric dams in Argentina which, when completed, would cover the daily electricity consumption of 1.5 million Argentine households, cut oil and gas import expenses, and even allow to export electricity to the neighboring countries. Milei’s simplistic vision of economic relations as mere exchanges between private actors sows doubts about the future of these projects.

Worse, their cancellation would risk seriously undermining Argentina’s credibility with international partners, even from ideologically more “compatible” countries.

The likely appointment of Diana Mondino, an economist, as the future minister of foreign affairs, has so far failed to assuage concerns about Milei’s policies. As evidenced in a pre-election debate organized by the Argentine Council on Foreign Relations, Mondino, who has spent her entire professional life in private sector, seems to share her future boss’ ideological view of international relations, as well as a penchant for hyperbole. A few days before the elections, she likened Milei’s possible victory to the fall of the Berlin Wall 34 years ago, as if the modern-day Argentina were in any way comparable to Soviet-backed communist dictatorships.

It is obviously too early to tell how the Milei presidency will unfold, but based on his rhetoric it may be a bumpy road ahead for foreign policy in Argentina.

https://responsiblestatecraft.org/javier-milei-argentina-foreign-policy/

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW..............

futbol.....

A court in Buenos Aires has blocked President Javier Milei's plans to open up Argentinian football to private investment. The issue continues to split the country's most popular sport, with some even looking to Germany.

READ MORE:

https://www.dw.com/en/argentina-court-blocks-milei-move-to-privatize-football/a-70122667

READ FROM TOP

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.