Search

Recent comments

- "benevolence"....

7 hours 49 min ago - trump's BoP is worse....

16 hours 13 min ago - luce's....

18 hours 13 min ago - dystopian....

1 day 4 hours ago - the fascists....

1 day 4 hours ago - not peaceful....

1 day 6 hours ago - 25 big helpers....

1 day 6 hours ago - courage....

1 day 8 hours ago - going nuts....

1 day 8 hours ago - oily law....

1 day 8 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

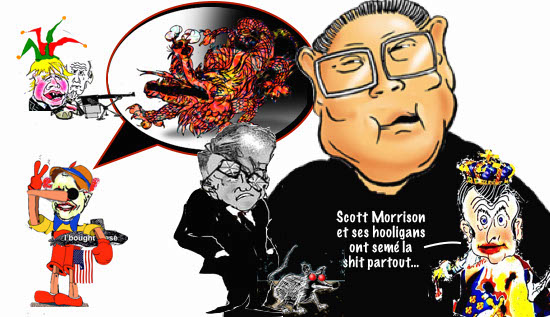

we don't need scumo's shitty submarines...

capers

capers

The sparsely populated, prosperous and peaceful country of Australia doesn’t often find itself dominating the news cycle, but for the last several days, it has been the focus of governments in the United States, China and the European Union, the great powers in a tri-polar world order.

Last week, Canberra, Washington and London reached agreement on a military pact reminiscent of the era of nuclear standoffs. The alliance, known as AUKUS, foresees Australia being outfitted with nuclear-powered submarines from the U.S. and Britain. It is a reaction to China’s rise to becoming the dominant economic and military power in the Indo-Pacific region.

Australia, located in the Far East but politically part of the West, lies on the fault line of the largest conflict of our times, the growing rivalry between China and the U.S.

With its close economic ties to China as a supplier of raw materials and foodstuffs, Australia recognized earlier than other countries the opportunities presented by Beijing's rise – and the risks. As early as the beginning of the last decade, the Australian government concluded that it needed to bolster its maritime power. The country tendered a multibillion-dollar contract for the construction of 12 conventionally powered submarines.

The deal, for which the German arms manufacturer ThyssenKrupp also submitted a bid, ultimately went to the Naval Group in France, with the first submarines scheduled for delivery in 2027. Officially, Canberra remained committed to the deal until just a few weeks ago, even as technical delays and spiraling costs threatened it with collapse. Then, last Thursday, Australia pulled the plug, announcing its alliance with Washington and London and backing out of the contract with the French.

The political consequences have been significant. Paris feels as though it has been hoodwinked by Australia and its NATO allies, the U.S. and Britain. France temporarily recalled its ambassadors from Washington and Canberra. In Brussels, meanwhile, the debate over Europe's "strategic autonomy" has been reopened and new questions have arisen regarding the efficacy of NATO, which French President Emmanuel Macron already referred to back in 2019 as "brain dead."

There is hardly a politician in existence who has a better handle on the background and the strategic consequences of this explosive arms deal than Kevin Rudd.

The 64-year-old served as prime minister of Australia from 2007 to 2010 before becoming foreign minister and then, in 2013, prime minister again for a brief stint. During his first and second tenures at the top, he was also the leader of the Australian Labor Party.

A sinologist by training, Rudd pursued a diplomatic career before entering politics, first in Stockholm and then in Beijing, where he closely followed the actions of the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party.

Today, Rudd is president of the Asia Society, a non-governmental organization based in New York, which is focused on deepening ties between Asia and the West.

DER SPIEGEL: Mr. Rudd, the 20th century was ravaged by two world wars, both of which began in Europe. Might we be facing a massive confrontation in the Pacific in the 21st century?

Kevin Rudd: It is quite possible. It is not probable, but it is sufficiently possible to be dangerous. And that is why intelligent statesmen and women have to do two things. First, identify the most effective guardrails to maintain the course of U.S.-China relations, to prevent things from spinning out of control altogether. And second, find a joint strategic framework, which is mutually acceptable in Beijing and Washington, to prevent crisis, conflict and war.

DER SPIEGEL: Germany was on the front lines of the Cold War. Now, in the current confrontation between the U.S. and China, Australia is exposed. Is today’s China as formidable and serious an adversary as the Soviet Union was 60 years ago?

Rudd: If we degenerate into a Cold War – which at this stage is probable and not just possible – then China looms as a much more formidable strategic adversary for the United States than the Soviet Union ever was. At the level of strategic nuclear weapons, China has sufficient capability for a second strike. In the absence of nuclear confrontation, the balance of power militarily, but also economically and technologically, is much more of a problem for the United States in the pan-Asian theater than was the case in Europe.

DER SPIEGEL: Your country, the U.S. and Britain have now entered into a new military alliance, which will provide Australia with a fleet of nuclear-powered submarines. What are the strategic considerations behind this decision?

Rudd: On the question of moving from conventional to nuclear-powered submarines, I have yet to be persuaded by the strategic logic. First, there is a technical argument that has been advanced about the range, detectability and noise levels of conventional submarines versus nuclear powered submarines. This is a technical debate which has not been fully resolved. If it is resolved in favor of nuclear-powered submarines, however, then another question arises.

DER SPIEGEL: Namely?

Rudd: We do not have a domestic civil nuclear industry, so how do we service these submarines? Which then leads to a third problem: If they have to be serviced in the United States and by the United States, does this lead us to a point where such a nuclear-powered submarine fleet becomes an operational unit of the U.S. Navy as opposed to belonging to a strategically sovereign and autonomous Royal Australian Navy? These questions haven't been resolved yet in the Australian mind, which is why the alternative government from the Australian Labor Party, while providing in principle support for the decision, insists that these questions have to be resolved.

DER SPIEGEL: What are the risks?

Rudd: We already knew in 2009 that it was important from an Australian national security perspective to have a greater capability of securing the air and maritime approaches to the Australian continent. So I launched a new defense white paper as prime minister, which recommended the construction of a new fleet of 12 conventionally powered submarines, which would make the Australian conventional submarine fleet the second largest in East Asia. The sudden change to a nuclear-powered option comes fully eight years after the conservative government of Australia inherited that defense white paper, commissioned tenders for it to be filled – which were won by the French contractor Naval Group in 2016 – and then proceeded to cancel the contract in the middle of the night in 2021. The Australian government has yet to provide a convincing strategic rationale for that decision. Nor has it been frank about the unspecified cost of building nuclear-powered boats through some sort of Anglo-American duopoly.

DER SPIEGEL: Either way, France has lost the contract. Do you understand their indignation?

Rudd: Absolutely. Australians take pride in the fact that we are people of our word. Such a U-turn is alien to our character. We don’t do these things. Secondly, if you reach a technical decision to commission nuclear-powered boats as opposed to conventional boats, then you have a duty to tell the French that the project specifications have changed and to invite them to retender for the new project. The French are perfectly capable of building and servicing nuclear-powered submarines. That is why the French, in my judgment, have every right to believe that they have been misled.

DER SPIEGEL: The German company ThyssenKrupp also submitted an offer to build the conventional submarines. In retrospect, was it a blessing for the Germans that they didn't win it?

Rudd: I regret to say that the current Australian government seems to exhibit what I would describe as a level of Anglophone romance which puzzles the rest of us in this country who are more internationalist in our world view.

DER SPIEGEL: Are you fundamentally in favor of Europe becoming involved militarily in the Indo-Pacific? Britain and France have warships in the region, and Germany has now joined them, with the frigate Bayern.

Rudd: These are obviously sovereign decisions in Berlin and Paris and London, and it depends on the aggregate naval capabilities of our European friends and partners. The more important question is that of developing a common strategy across the board – military, diplomatic, economic – to deal with the problematic aspects of China's rise. Not all the aspects of China's rise are problematic, but in a number of them, China is seeking to change the international status quo. The current Australian government's torpedoing of the submarine contract with France actually renders the possibility of a common, global allied strategy for dealing with China's rise more problematic and more difficult rather than less.

DER SPIEGEL: Australia, the United States, Japan, and India are members of a loose group of four nations concerned about China's rise. Is this "Quad" the nucleus of an Indo-Pacific NATO?

Rudd: I think this is a false analogy. NATO has mutual defense obligations. That is not the case with Japan and Australia because we are part of separate bilateral security arrangements with Washington, not a multilateral arrangement. And India is not an ally because it has no formal alliance structure. I think it is unlikely for the foreseeable future that the Quad would evolve into a NATO-type arrangement. However, the Chinese take the Quad seriously because it is becoming a potent vehicle for coordinating a pan-regional strategy for dealing with China's rise.

DER SPIEGEL: Australia and Germany have extremely close economic ties with China. Have our countries become too dependent on Beijing?

Rudd: Any modern economy does well to diversify. Under Xi Jinping, China's economic strategy has become increasingly mercantilist. If you are the weaker party in dealing with a mercantilist power, then you will increasingly have terms dictated to you. Another point is this: China's domestic economic policy is moving in a more statist and less market-oriented direction. We have to ask ourselves whether this will begin to impede China's economic growth over time and whether China will be as robust in the future. All these are reasons for not pinning all global growth, all European and German export growth, on the future robustness of this one market.

DER SPIEGEL: Australia has been economically punished by China, in part because your government has called for an independent investigation into the origin of the coronavirus pandemic. What can other countries learn from Australia’s experience?

Rudd: The critical lesson in terms of China's coercive international diplomacy is that it's far better for countries to act together rather than to act independently and individually. If you look at Beijing’s punitive sanctions against South Korea, against Norway and now against Australia, the Chinese aphorism can be applied everywhere: "sha yi jing bai,” kill one to warn 100. Therefore, the principle for all of us who are open societies and open economies is that if one of us comes under coercive pressure, then it makes sense for us all to act together. And if you want a case study to see how that could be effective, look at the United States. When was the last time you saw the Chinese adopt major coercive action against the U.S.? They haven't because the U.S. is too big.

DER SPIEGEL: A few days ago, the European Union announced its strategy for the Indo-Pacific. Brussels plans to rely less on military means against China and more on closer cooperation with China's neighbors – on secure and fair supply chains, and on economic and digital partnerships. What do you think of this approach?

Rudd: In the recent past, the logic in Brussels and many European capitals was pretty simple and went like this: First, China is a security problem for the United States and its Asian allies, but not us in Europe. Second, China presents an economic opportunity for us in Europe, which should be maximized. And third, China represents a human rights problem, which occasionally we'll engage in with some appropriate forms of political theater. That was the logic, if I may summarize recent history in such a crude Australian haiku.

DER SPIEGEL: You may!

Rudd: But now, this has evolved. Europeans have experienced cyberattacks of their own. Germany in particular has experienced the consequences of Chinese industrial policy and the aggressive acquisition of German technology, as well as the strategic collaboration between China and Russia, which is now almost a de facto alliance. When I see this evolution reflected in the posture of the G-7, of NATO and of the of the European Union, it's pointing in a certain direction. The Europeans have finally concluded that China represents a global challenge. The Asia-Pacific region has now evolved westwards, to the Indo-Pacific, through the Suez Canal and into the Mediterranean and Europe itself. China is a global phenomenon, both in terms of opportunities and challenges. There's not a single country from Lithuania to New Zealand which is not being confronted with the reality of China. China cannot simply be put to one side and regarded as someone else's problem.

DER SPIEGEL: German Chancellor Angela Merkel has geared her China policy to Germany's economic interests and has often been criticized for doing so. Do you agree with this criticism? And what advice would you give Merkel's successor?

Rudd: I know Angela Merkel reasonably well; she was chancellor when I was prime minister. She is a deeply experienced political leader, respected around the world. And to be fair, the China that she encountered when she first became chancellor under Hu Jintao was a quite a different China to the one which has evolved since the rise of Xi Jinping. In fact, the China of Xi’s first term was different to the China after the 19th Party Congress …

DER SPIEGEL: … when term limitations for his presidency were eliminated.

Rudd: Since then, I have detected some change in the German position. Germany could have vetoed the approaches adopted by the G-7, NATO and the EU. But it chose not to. So if there is some skepticism in the world about German foreign policy under Merkel, it is because Germany has been robust multilaterally in its response to China and much more accommodating bilaterally.

DER SPIEGEL: What does this mean for the next government?

Rudd: Our German friends need to know that the rest of the world observes German politics very closely. And there's a reason why we do that: Of all Western countries outside the United States, China has the deepest respect for Germany. This has to do with the economic miracle after World War II, the depth of German manufacturing, and the remarkable living standards Germany has been able to generate while still maintaining a posture of environmental sustainability. So when it comes to China, Germany is not just another country. It is the one Western country, outside the United States, which the Chinese predominantly respect.

DER SPIEGEL: After the recent announcement of AUKUS, the security pact between Australia, the UK and the U.S., former British Prime Minister Theresa May warned of the consequences of a military escalation, specifically in the Taiwan Strait. How do you rate this risk?

Rudd: I do not think either Beijing or Washington want a war over the Taiwan Strait as a matter of deliberate policy. Certainly not Beijing in this decade, since it is not yet ready to fight and is still in the middle of a reorganization of its military regions and its joint command structures. Another question is whether an accident could happen, similar to what happened in 1914 after the assassination of the Austrian archduke, which led to the outbreak of World War I.

DER SPIEGEL: What exactly do you have in mind?

Rudd: There are multiple possibilities. A collision of military aircraft or naval vessels, for example. Or some unilateral act by an incoming Taiwanese government – not the current one – taking a much more decisively independent view, could trigger a crisis.

DER SPIEGEL: How could such a crisis be prevented?

Rudd: Crisis management in 2021 may not be that much better than in July of 1914. Therefore, the danger is not war as a consequence of intentional policy action. It's war as a consequence of miscalculation.

DER SPIEGEL: In his book "The Sleepwalkers,” your compatriot, the historian Christopher Clark, described how Europe's alliances mobilized each other into World War I in 1914. Is such a scenario really still conceivable today?

Rudd: Those of us who are looking carefully at the evolution of East Asia began rereading the history of World War I long ago. The possibility of an open, land-based missile conflict between Chinese and American forces in the East Asian Pacific is as real now as an escalation was then. Even worse, because the mobilization times, in terms of getting people on trains back then, were far longer than now.

DER SPIEGEL: What about the danger that military alliances will put pressure on each other?

Rudd: We do have an aggregation of alliances even today. China may have no formal allies, but Russia, in the event of a conflict, could well take action on behalf of its Chinese friends. We cannot over-study World War II in terms of the warnings it sends to all of us about unintended consequences. For that reason, I have written a book which will come out early next year. I've just sent it to the publishers. The title is "The Avoidable War.”

DER SPIEGEL: Mr. Rudd, we thank you for this interview.

Read more:

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

- By Gus Leonisky at 27 Sep 2021 - 7:13am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

appalling political leadership...

BY John McCarthy, AO — a senior advisor to Asialink and former Australian Ambassador to the United States, Indonesia and Japan, and High Commissioner to India.

The main British objective under their appalling political leadership seems to be to find something meaningful to do after the Brexit debacle .. Joe Biden could not even remember Scott Morrison’s name?

Former British prime minister Harold Wilson was quoted — possibly apocryphal — as saying that a week is a long time in politics. This has been a very long week.

On most hard issues, policy is a viscous, not a clear-cut, commodity. So the advocates and opponents of AUKUS won’t have a walkover on what is the best boat for Australia.

Australians lacking a phobia about things nuclear will see the merits of more powerful boats and a stronger navy (let us leave it to the experts as to which boats can move more stealthily though our northern approaches). For the old-fashioned anti-nuclear crowd, time has moved on.

If we are to change to nuclear-power ships, why did we not go all the way five years ago? Where was the problem then? The Americans had size and clout. The British boats worked. So did those of the French.

Was it impossible to persuade the Australian public of the merits of nuclear-powered boats? We never even tried. And yes, there was a China threat then as well.

Whatever might have been, we have now charted a clearer course on boats. But why this course?

The Brits are a skillful bunch, but the Americans know more about submarines. The main British objective under their appalling political leadership seems to be to find something meaningful to do after the Brexit debacle – unless there exists some arrangement between the US and the UK about which we Australians are in the dark. Maybe a British boat would be a better one for our needs. It will be interesting if Uncle Sam agrees.

The widely publicised visit of a British aircraft carrier to the Asia-Pacific region this year did not include dropping in for a beer in an Australian port.

So keep families together, yes. Honour our dead together, yes. But less cant about strategic cooperation. And please, please, don’t seek to mimic the US-Australian mateship nonsense.

And what about the French? We remain anglophiles under our thin wreath of multiculturalism. We forget that in Europe — after Brexit — Germany and France are more powerful than the British. The French remain a Pacific nation — a big one. The total British diplomatic presence in the Pacific might equal in numbers their diplomats in a couple of Balkan states.

Why did the Americans go quite so far in rescuing us from our submarine fiasco when Joe Biden could not even remember Scott Morrison’s name? The US president clearly wanted to get the Afghan disgrace off the front pages. More important, Biden now sees China as a bigger strategic threat than Russia — and it is.

But we forget the offence to one of America’s three most important European allies given its issues with Russia, the Ukraine and the Baltics? The Americans must have calculated the damage to NATO through the deception of France at the Cornwell meeting with Biden and Morrison.

The depth of the mistakeBiden did not anticipate the depth of the French reaction, According to senior Washington sources, this was partly because the Americans could not believe the crassness with which the matter was handled by Australia. But that is not enough to explain the depth of the mistake.

However, for us — hype aside, the saddest thing about the recent shift is it diminishes the serious Australian diplomatic effort with Asia over 50 years or so, including the post-Vietnam bolstering of ASEAN, the building of APEC and so on.

We were never to be Asians — nor should we have been. But we were able to become an erstwhile British Dominion, which successfully developed strong regional links with our emergent postcolonial neighbours.

Post World War II, there were three main tenets to our foreign policy — a constructive role in the post-war multilateral order; the protective shield of ANZUS; and engagement with Asia.

Donald Trump did much to destroy the post-war order ANZUS has taken on — a new, and almost sacred, structure not foreseen before the growth of China.

And rather than spending political energy on our immediate region on how to handle the new world cleverly and in our regional interests, we now seem to be snuggling up again to our erstwhile great and powerful friends — most comfortable in the all-white Five Eyes circle.

Yes! Some will say, what about the QUAD? It comprises Europeans and Asians. Careful! Good to have Japan — wealthy, and the best diplomats in Asia. But constitutional impediments to military activity remain, and there exist deep divisions in its polity between nationalism and pacifism.

The Indians have been enemies of China since the 1960s border war. They will go where their interests dictate. They will not veer from their doctrine of strategic autonomy. They have never much liked the QUAD. It is now more valuable to them, but it will never be an ANZUS or AUKUS.

In ASEAN, not all would eschew big Australian boats. But few see merit in further injections into the region of mutual Chinese-American hostility.

So let us not get carried away with AUKUS. It symbolises that the Americans are very serious about Asia and on a lesser scale about dampening down Australia’s insecurities. Good.

But we are moving fast from being a country with the self-respect of true independence.

Read more:

https://johnmenadue.com/aukus-we-are-moving-fast-from-being-a-country-with-the-self-respect-of-true-independence/

Read from top.

dutton's is dangerous...

Peter Dutton’s support for the US over China risks putting wind beneath the wings of Washington’s hawks. We have been here many times before.

Defence Minister Peter Dutton declared last month that if it came to US action against China over Taiwan, “it would be inconceivable that we wouldn’t support the US”. Are there warnings from history we should heed here?

Two days later, the US journal Politico’s “National Security Daily” wondered aloud: might commentary like Dutton’s encourage the more belligerent voices in Washington ready to risk war? Perhaps “having Canberra on Washington’s side in case a still unlikely war breaks out might make the calculation easier”.

We have been down this path before — but further back than the 1930s, Dutton’s go-to decade which he imagines provides the imperishable lesson that only superior weapons and alliances can keep the peace. Let us look instead to the decade before 1914.

Australian ministers spoke in terms identical to those of Dutton’s at a meeting of the British Committee of Imperial Defence in London on May 29, 1911. Australian Labor prime minister Andrew Fisher told the British that in the event of war he wanted Australia’s navy to be “part of the British fleet, and to cooperate in every possible way”. He added that “I can hardly conceive of a national circumstance where it would not cooperate heartily”.

At the same meeting, George Pearce, Labor’s defence minister, declared that keeping out of any conflict was not possible for Australia: “I say it is inconceivable in my opinion that it would take that attitude.” Naval unity of command was “unquestionably’ essential”. He assured the British that in practice “you can always count the [Australian] fleets in”.

How had Australian politicians got to this point? It is a lesson in the dangers of setting up deterrence and alliance as the nation’s household gods.

Let us step back. In the decade before the Great War, the British empire’s decision-makers persuaded themselves that they faced a threat from a new rising power, Germany — notwithstanding growing trade relations. Military and imperial-loyalist lobby groups in Australia drank in this doctrine and preached the need for Australia to achieve security through a massive increase in military spending and unwavering loyalty to Britain. Compulsory military training began, and a “Royal Australian Navy” took shape. From 1908-09 to 1913-14, Commonwealth spending on defence doubled, from 15.5 per cent to 31 per cent of the federal budget.

Alliances became objects of worship. How did Australia get caught up in these? One day in April 1904, Australians woke up to read in their newspapers that, courtesy of the British Foreign Office, they were now in a new kind of alliance — an “Entente Cordiale” — with France, based on Anglo-French plans for mutual expansionism in Egypt and Morocco. No one consulted Australia.

Then, one day in early September 1907, Australians woke up to read that Tsarist Russia was now their ally; an “Anglo-Russian convention” had been signed in St Petersburg, based upon a contemplated partition of Persia. Neither Parliament nor the people had been consulted.

It was Liberal prime minister Alfred Deakin’s minister, Colonel Justin Foxton, who next entangled Australia. At the Imperial Defence Conference in London in 1909, he signed up to a sweeping declaration that Australia would “take its share in the general defence of the empire”. He also agreed that the Australian navy, which was slated for rapid expansion, would be swiftly transferred to the British Admiralty in the event of war.

Periodically, Australian politicians ducked and weaved on these issues. For example, on his way home from London in mid-1911, Fisher was reported as saying that if Britain embarked upon an unjust war, then Australia might have to decide “to haul down the Union Jack and hoist our own flag and start on our own”. All hell broke loose, and Fisher buckled. He was forced to deny in Parliament that he had ever said or intended such a thing. Australia was locked in.

Many other politicians, such as George Reid, George Pearce, and William Morris Hughes, stressed in public speeches that Australia must be ready to deploy its military forces well beyond its borders, at Britain’s command — “forward defence”. As defence minister, Pearce emphasised Australia’s dependence on Britain and conceded that Australia “may at any time be involved in a war in the causing of which we had no voice”. Being drawn into war “willy nilly” was inescapably the cost of “our imperial connexion” (August 18, 1910). Thus, in late 1912, Pearce secretly authorised planning for an expeditionary force to be despatched upon the outbreak of war — that is, in virtually any war that Britain chose.

When a European war loomed in late July 1914, Australia’s politicians accepted that the decision for war or peace was London’s. With a federal election due in weeks, they competed with each other in a love-of-empire auction. “Last man, last shilling”.

In early August 1914, the crisis in Europe exploded. A mere rump of Australian Liberal prime minister Joseph Cook’s cabinet authorised the despatch of a cable to London in the early evening of Monday, August 3 (or Monday morning, London time) offering an expeditionary force of 20,000 men, to be entirely at London’s disposal and at Australia’s cost. This was some 40 hours in real time before Britain declared war at all. Looking to scoop up advantage in the coming election by unleashing the khaki factor, the government released the cable to the press.

In London, British colonial secretary Lewis Harcourt was cool. He replied to Australia that “there seems to be no immediate necessity for any request on our part for an expeditionary force from Australia”. Irritated, he told cabinet that he was “holding back” these forces. Australia had jumped the gun.

What impact did this offer have in Britain? In the last days of peace, Britain’s Liberal cabinet was deeply divided. Initially, four Liberal ministers resigned, denouncing rash promises of naval assistance to France and a perceived failure to restrain Russia. Meanwhile, blood-and-thunder politicians and journalists pressing for an instant British intervention gleefully flaunted the Australian offer. Chiming in, The Times declared it “unthinkable” that Britain could stay out of war when “our brethren overseas” were so “resolute”. It heaped praise on the Australians who had “swept away the phrases of weakness and indifference and ranged their manhood at our side”. Britain declared war very late on Tuesday, August 4.

Did Australia’s early offer embolden the “hawks”? It certainly shocked British prime minister H. H. Asquith. Soon after deciding for war, he told a colleague how surprised he had been to read the “messages from the dominions declaring their intentions to sally forth and attack whatever German possessions might be in their neighbourhood”. “Isn’t this extraordinary?” Asquith exclaimed.

Are there warnings for us here? If we suggest that our not participating in war as a comrade-in-arms with our powerful ally is “inconceivable” — as we did in 1911 and as Dutton does today — do we not risk inciting reckless decision-makers? In a nuclear age, are we not exposing our people to perils beyond our imagination?

READ MORE: “Dutton’s war talk election tactics need calling out” — The Australian Financial Review

Read more:

https://johnmenadue.com/dutton-leads-us-down-a-dangerous-pre-world-war-i-path/

READ FROM TOP.

dutton is out of control...

Former Prime Minister Paul Keating’s recent National Press Club address on Australia’s relationship with China has led to a storm of criticism from the right-wing militarist brigade who seem to be salivating at the prospect of front row seats for WWIII.

Minister for Defence Peter Dutton hit the airwaves to inform us that Keating is “out of control and damaging our country”, accusing him of being a “grand appeaser” for making the entirely reasonable point that “Australia should not be drawn ... into a military engagement over Taiwan—US-sponsored or otherwise”.

To make the stakes of this debate crystal clear, Dutton told the Australian on 13 November that, in regard to Taiwan, it “would be inconceivable that we wouldn’t support the US in an action if the US chose to take that action”. Scott Morrison also rejected Keating’s views on the Today show and explained, “As people know, we’ve taken a very strong position here in the Indo-Pacific and we’ve taken a very strong stance standing up for Australia’s interests”.

It’s not just the warmongers in the Liberal Party expressing outrage over Keating’s comments. Peter Hatcher, who has spent years beating the war drums against China, in an opinion piece for the Sydney Morning Herald on 16 November, admits, “[I]t would be a grave decision to join the US and Japan and go to war against China”, but goes on to argue that “the alternative would be grave, too” and that history “has shown the futility of appeasing aggressive dictators”.

The ALP has also distanced itself from the views of its former leader. Richard Marles, deputy federal leader of the party, said that while Keating is “entitled to his view ... Labor have made it completely clear the challenges that China represents”. And Marles is right—the ALP has worked in lockstep with the Liberals over the question of China.

Keating is not some principled anti-imperialist. His argument largely hinges on the idea that supporting Taiwan isn’t in Australia’s “national interest”, and his views are rooted in an older geopolitical tradition that has emphasised the opportunities for Australian capitalism in further engagement rather than confrontation with China—a view that until recently was dominant in Canberra.

That a more aggressive stance on China has emerged as the new consensus among much of the Australian establishment is a dangerous development. In particular, gaining wider traction is the idea that Australia is a weak nation being undermined by a soft business class of China appeasers, which leaves us wide open to invasion. This argument is being used to break down the healthy suspicion of militarism and war that has embedded itself in the population after years of unpopular military interventions in the Middle East.

The most shocking thing about the state of debate in Australia over China is how blasé it is to the prospect of initiating military action that could end in tens or perhaps hundreds of thousands of deaths.

And for what purpose? Much is made of the need to defend Taiwan’s “little democracy” from Chinese aggression. But while Taiwan’s right to self-determination should be respected, military intervention by the US, Australia and others into a conflict over the region would most likely end in a bloodbath in which Taiwanese rights would be totally subordinated in a militarist free-for-all between the major players in world geopolitics.

After all, Australia and the US are hardly principled defenders of the self-determination of nations, as a cursory look at the history of Western intervention into the Middle East shows. What they care about is the challenge that China poses for the continued dominance of Western powers over the international political system, not the rights of the Taiwanese or anybody else.

Read more:

https://redflag.org.au/article/war-hawks-rampage-over-china

Read from top.