Search

Recent comments

- friend-ships.....

23 min 3 sec ago - the lobby....

1 hour 20 min ago - not worth...

2 hours 30 min ago - illegal stuff....

3 hours 20 min ago - no shipping.....

13 hours 8 min ago - digging graves....

13 hours 20 min ago - BS draft...

13 hours 28 min ago - tankers ablaze....

14 hours 15 min ago - shoes....

16 hours 13 min ago - new map....

16 hours 47 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

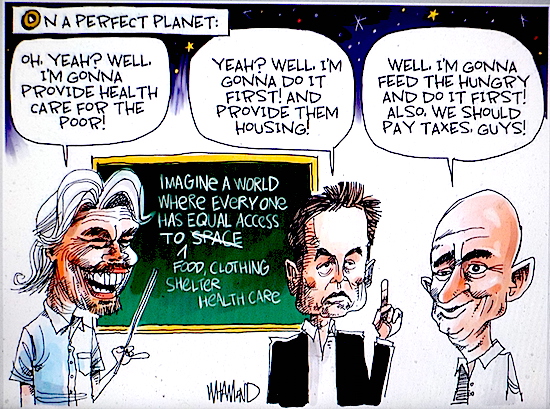

one-upmanship...

Elon Musk’s SpaceX on Friday shared more images from inside its Crew Dragon capsule that’s already brought its four civilian passengers around the Earth more than 15 times, according to the mission, dubbed “Inspiration4.”

One image, shared shortly after midnight, shows the whole crew — Jared Isaacman, Hayley Arceneaux, Chris Sembroski and Dr. Sian Proctor — floating in microgravity as they orbit the planet.

“The crew of #Inspiration4 had an incredible first day in space!” the mission’s official account tweeted along with the images. “They’ve completed more than 15 orbits around planet Earth since liftoff and made full use of the Dragon cupola.”

Another photo shows Isaacman, the 38-year-old billionaire founder of payments processing firm Shift4 Payments and “mission commander” of Inspiration4, peering out the cupola of the capsule with a gaping view of Earth behind him.

Isaacman, who has an estimated net worth of $2.4 billion, paid an undisclosed sum to SpaceX to commission the flight, with Time Magazine pegging the figure at $200 million.

Another shot shows Arceneaux — a 29-year-old childhood bone cancer survivor who’s now a physician assistant at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital — looking back toward Earth from the capsule’s altitude of 335 miles — about 75 miles higher than the International Space Station and on a level with the Hubble Space Telescope.

And the last snap shared Friday shows Sembroski, a 42-year-old Air Force veteran and aerospace data engineer at Lockheed Martin, looking through what appears to be a telescope from the capsule’s cupola.

All four amateur astronauts have been training for months since the flight crew was announced in March.

Read more: https://nypost.com/2021/09/17/spacex-releases-more-photos-as-civilian-crew-orbits-earth/

Note: cartoon above from the net somewhere...

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW, PLEASE !!!!!!!!!!!!!

- By Gus Leonisky at 19 Sep 2021 - 5:16am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

docking payslips...

A year ago, Tara Jones, an Amazon warehouse worker in Oklahoma, cradled her newborn, glanced over her pay stub on her phone and noticed that she had been underpaid by a significant chunk: $90 out of $540.

The mistake kept repeating even after she reported the issue. Ms. Jones, who had taken accounting classes at community college, grew so exasperated that she wrote an email to Jeff Bezos, the company’s founder.

“I’m behind on bills, all because the pay team messed up,” she wrote weeks later. “I’m crying as I write this email.”

Unbeknown to Ms. Jones, her message to Mr. Bezos set off an internal investigation, and a discovery: Ms. Jones was far from alone. For at least a year and a half — including during periods of record profit — Amazon had been shortchanging new parents, patients dealing with medical crises and other vulnerable workers on leave, according to a confidential report on the findings. Some of the pay calculations at her facility had been wrong since it opened its doors over a year before. As many as 179 of the companies’ other warehouses had potentially been affected, too.

Amazon is still identifying and repaying workers to this day, according to Kelly Nantel, a company spokeswoman.

That error is only one strand in a longstanding knot of problems with Amazon’s system for handling paid and unpaid leaves, according to dozens of interviews and hundreds of pages of internal documents obtained by The New York Times. Together, the records and interviews reveal that the issues have been more widespread — affecting the company’s blue-collar and white-collar workers — and more harmful than previously known, amounting to what several company insiders described as one of its gravest human resources problems.

Workers across the country facing medical problems and other life crises have been fired when the attendance software mistakenly marked them as no-shows, according to former and current human resources staff members, some of whom would speak only anonymously for fear of retribution. Doctors’ notes vanished into black holes in Amazon’s databases. Employees struggled to even reach their case managers, wading through automated phone trees that routed their calls to overwhelmed back-office staff in Costa Rica, India and Las Vegas. And the whole leave system was run on a patchwork of programs that often didn’t speak to one another.

Some workers who were ready to return found that the system was too backed up to process them, resulting in weeks or months of lost income. Higher-paid corporate employees, who had to navigate the same systems, found that arranging a routine leave could turn into a morass.

In internal correspondence, company administrators warned of “inadequate service levels,” “deficient processes” and systems that are “prone to delay and error.”

The extent of the problem puts in stark relief how Amazon’s workers routinely took a back seat to customers during the company’s meteoric rise to retail dominance. Amazon built cutting-edge package processing facilities to cater to shoppers’ appetite for fast delivery, far outpacing competitors. But the business did not devote enough resources and attention to how it served employees, according to many longtime workers.

“A lot of times, because we’ve optimized for the customer experience, we’ve been focused on that,” Bethany Reyes, who was recently put in charge of fixing the leave system, said in an interview. She stressed that the company was working hard to rebalance those priorities.

The company’s treatment of its huge work force — now more than 1.3 million people and expanding rapidly — faces mounting scrutiny. Labor activists and some lawmakers say that the company does not adequately protect the safety of warehouse employees, and that it unfairly punishes internal critics. This year, workers in Alabama, upset about the company’s minute-by-minute monitoring of their productivity, organized a serious, though ultimately failed, unionization threat against the company.

In June, a Times investigation detailed how badly the leave process jammed during the pandemic, finding that it was one of many employment lapses during the company’s greatest moment of financial success. Since then, Amazon has emphasized a pledge to become “Earth’s best employer.” Andy Jassy, who replaced Mr. Bezos as chief executive in July, recently singled out the leave system as a place where it can demonstrate its commitment to improve. The process “didn’t work the way we wanted it to work,” he said at an event this month.

In response to the more recent findings on the troubles in its leave program, Amazon elaborated on its efforts to fix the system’s “pain points” and “pay issues,” as Ms. Reyes put it in the interview. She called the erroneous terminations “the most dire issue that you could have.” The company is hiring hundreds of employees, streamlining and connecting systems, clarifying its communications and training human resources staff members to be more empathetic.

But many issues persist, causing breakdowns that have proved devastating. This spring, a Tennessee warehouse worker abruptly stopped receiving disability payments, leaving his family struggling to pay for food, transportation or medical care.

“Not a word that there had ever been a problem,” said James Watts, 54, who worked at Amazon in Chattanooga for six years before repeated heart attacks and strokes forced him to go on disability leave. The sudden loss of his benefits caused a cascade of calamities: Because he was without pay for two weeks, his car was repossessed. To afford food and doctors’ bills, Mr. Watts and his wife sold their wedding rings.

“We’re losing everything,” he said.

Read more: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/24/technology/amazon-employee-leave-errors.html

Read above...

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW ÏÏÏÏÏÏÏÎÎΩ©©©©©©©ÓÓÓÓÓÓÍÔÔÔÓÓÓ˝˝˝°°°°°°••••••

paid leave...

The U.S. is one of six countries with no national paid leave. The Democrats have cut their plan to four weeks, which would still make it an outlier.

Congress is now considering four weeks of paid family and medical leave, down from the 12 weeks that were initially proposed in the Democrats’ spending plan. If the plan becomes law, the United States will no longer be one of six countries in the world — and the only rich country — without any form of national paid leave.

But it would still be an outlier. Of the 185 countries that offer paid leave for new mothers, only one, Eswatini (once called Swaziland), offers fewer than four weeks. Of the 174 countries that offer paid leave for a personal health problem, just 26 offer four weeks or fewer, according to data from the World Policy Analysis Center at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Four weeks would also be significantly less than the 12 weeks of paid parental leave given to federal workers in the United States, and less than the leave that has been passed in nine states and the District of Columbia.

Paid leave is part of the Democrats’ giant budget proposal, which includes other family policies like child and elder care. They are trying to cut to an amount palatable to Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Senator Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, whose votes are needed to pass it. For paid leave, decreasing the number of weeks is a simple way to lower the price.

Some leave is better than none, researchers said, but evidence from around the world suggests that four weeks is too little to reap the full benefits.

“When you look at other countries, there is evidence of what people need and what’s feasible,” said Jody Heymann, founding director of the policy center and a U.C.L.A. distinguished professor of public health and public affairs. “And by both of those measures, 12 weeks is a modest amount, and anything less is grossly inadequate. The rest of the world, including low-income countries, have found a way to do this.”

Globally, the average paid maternity leave is 29 weeks, and the average paid paternity leave is 16 weeks, the center’s data shows.

There is one element of the paid leave proposal, however, that would put the United States at the forefront internationally: its very broad definition of family and caregiving. It would cover care for all types of loved ones, including in-laws, domestic partners and people who are the “equivalent” of family.

About half of countries allow caregiving leave for sick children. Thirty-nine percent of nations allow it for adult relatives like spouses or parents. Among countries that have leave for family health needs, only 13 define family broadly, including grandparents or other loved ones. Even then, there are sometimes restrictions, like proving that the person needing care is dying.

Globally, 107 countries have parental leave available to fathers, which is more than half, and 47 offer more than four weeks. Many rich countries offer more than 12 weeks. Twenty, including Japan, Canada and Sweden, have options for more than a year.

For proponents of paid leave in the United States, the broad definition of caregiving for loved ones has been a key demand. “We have always fought for a family definition that reflects what American families really do look like, including chosen family,” said Lelaine Bigelow, vice president for congressional relations at the National Partnership for Women and Families. “This has been a big pillar of ours for a long time.”

Existing family leave policies in the United States already have a broad definition of caregiving, largely because the country came around to offering leave so late. Many countries started paid maternity leave in the 1920s. The American leave program — unpaid and for 12 weeks, for about half of workers — started in 1993. By that point, gender norms had evolved and it was common for mothers to work and men to care for children or relatives. The unpaid leave covers people caring for babies; sick spouses, parents or children; or their own medical conditions.

Paid leave is rarely fully paid anywhere; the pay is usually a percentage of the regular salary up to a certain maximum. Around the world, paid leave is generally financed through social insurance, via taxes or contributions from employers and workers. The states with paid leave have a similar system.

The federal plan in Congress is limited by the rules of a budget process called reconciliation, and would be paid for, along with other safety net spending, with general revenue, perhaps from a tax on billionaires.

Read more:

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/25/upshot/paid-leave-democrats.html

Read from top

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW ≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈