Search

Recent comments

- unrest....

53 min 57 sec ago - disinformation...

8 hours 38 min ago - poisoned dart?....

11 hours 58 min ago - narrative control....

16 hours 5 min ago - chabad....

21 hours 21 min ago - back to the kitchen....

21 hours 23 min ago - loneliness....

23 hours 32 min ago - insight....

1 day 3 min ago - conspiracy....

1 day 19 hours ago - brutal USA....

1 day 21 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

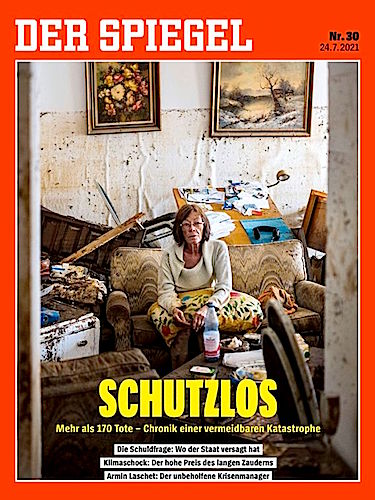

defenceless...

defenceless

defenceless

A thick, dark blue stripe runs across one of the flood maps of Erftstadt – subcatchment Erft, map sheet B002 – in the western German state of North Rhine-Westphalia.

The strip marks a section of Federal Road 265, and its color means that, in the event of a flood, it faces the greatest level of danger, with water potentially reaching up to 4 meters (around 13 feet) or higher. It means the road could become a deathtrap.

In other words, one could have known. Or rather, one should have known.

At the beginning of last week, the German Meteorological Service (DWD) issued a warning about severe storms. On Wednesday, Erftstadt’s basements filled up, the fire department was operating without pause and it kept raining in the early hours of Thursday. But nobody in the small town thought of closing the road to traffic. By Thursday morning, though, it was too late.

A thick, dark blue stripe runs across one of the flood maps of Erftstadt – subcatchment Erft, map sheet B002 – in the western German state of North Rhine-Westphalia. The strip marks a section of Federal Road 265, and its color means that, in the event of a flood, it faces the greatest level of danger, with water potentially reaching up to 4 meters (around 13 feet) or higher. It means the road could become a deathtrap.

In other words, one could have known. Or rather, one should have known.

At the beginning of last week, the German Meteorological Service (DWD) issued a warning about severe storms. On Wednesday, Erftstadt’s basements filled up, the fire department was operating without pause and it kept raining in the early hours of Thursday. But nobody in the small town thought of closing the road to traffic. By Thursday morning, though, it was too late.

What’s going wrong, and how can it be changed?

It’s morning on Monday, July 12, and the German Meteorological Service sends out "advance storm information,” a first indication "of a weather situation with high potential for severe weather.” It warns that local precipitation of up to 200 liters per square meter could fall in southern North Rhine-Westphalia. At 5:55 p.m., an official severe weather warning follows for the regions northwest of Saarbrücken, ranging from the Eifel to Hagen in North Rhine-Westphalia. The meteorologists predict "abundant continuous rain” from the period from Tuesday to Thursday as well as areas of heavy rain. The warning is sent to all affected districts, flood-control centers and the Federal Office of Civil Protection and Disaster Assistance (BBK) in Bonn. This is how the reporting protocol is meant to work.

But what consequences do these severe weather warnings have? That’s where the DWD’s responsibility ends. "We lack the local knowledge to derive actions from the weather forecast,” the federal office explains. Those 200 liters of rain, it says, would have a very different impact in low-lying areas than in low mountain ranges with many slopes.

This is where the problem starts. The German states, and in many cases the local districts, are responsible for disaster management, and it is they who should have had to translate what the meteorologists’ predictions mean on the ground. "With 200 liters, the warning bells actually should have been ringing,” says Albrecht Broemme, who was the president of the Federal Agency for Technical Relief until the end of 2019. "But in the end, it was probably just one of many, many warnings that come into the coordination centers.”

Like in Erftstadt. There, the first severe weather warnings reach the fire department’s control center on Monday, days before the flood. Apparently, nobody in the district recognizes the danger and the messages go nowhere. On Wednesday, the heavy rain begins, and the water does not seep away, but instead pours into the basements. Frank Rock, the district administrator of the Rhine-Erft district, is on vacation in France and hopes to go to the Atlantic. His treasurer calls him, and that evening Rock decides to establish a crisis team. He breaks off his vacation the next day – but by then the disaster has long since begun.

At 11 p.m. on Wednesday, the first patients are brought to safety at the Marien Hospital, with flooding imminent. The district sends out several warnings to the population and local media via the "Nina” warning app, but the sirens in Erfstadt don’t sound until Thursday morning, at 8:51 a.m. in the Bliesheim district. At 10:16 a.m., the alarm sounds in Blessem, about 5 kilometers away. Should they have been better prepared?

Read more:

https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/left-to-their-own-defenses-

catastrophic-flooding-spotlights-germany-s-poor-disaster-

preparedness-a-b3821147-97d2-4f23-951c-0206bd9ff9b2

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW ††††††††††††††††!!!!

- By Gus Leonisky at 27 Jul 2021 - 5:08am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

global warming is real...

bigger than planned for...

They were prepared. Several years ago, in 2014, the hospital management had an expert report prepared at the request of the City of Leverkusen. The aim was to clarify whether the hospital was protected from flooding. Its buildings are located right next to the Dhünn River, which winds around the clinic grounds, a gentle 40-centimeter (16-inch) deep body of water in normal times.

The hospital’s technical rooms are located 12 meters (around 40 feet) from the edge of the river. They house the control center for the normal power source, as well as the emergency power. The specialist recommended installing sheet pile walls, just in case. That were fitted, and everyone was satisfied.

The expert’s report claimed that the hospital was protected and argued that it would hold up even during a massive flood. In other words, that it would be safe in the event the water reached a level that statistically only occur once every 100 years. Those were the city’s specifications.

Shortly after 7 p.m. on the evening of July 11, the water began spilling over the banks of the Dhünn. At 7:12 p.m., water sloshed over the street. The heavy rain had caused the Dhünn to rise almost 3 meters. The rooms in the hospital’s basement and its underground parking garage filled up. The water flooded corridors as well as the technical rooms. Around 10 p.m., the electricity went out. The emergency supply took over, but the responders were afraid it might go out as well.

At that point, there were 468 patients in the hospital. The automatic oxygen supply failed, and nurses ran to bring bottles of it to their beds. Equipment that was critical to people’s survival like cardiopulmonary machines had to be run on emergency batteries. The phone system, the computers and their servers were all down.

By midnight, it was clear the power would not be restored. The patients had to be evacuated immediately. During the night, they evacuated the premature infants ward, the intensive care unit and the stroke unit, followed by the other departments the next day. With the elevators out of commission, rescue workers had to carry critically ill patients through the stairwell, along with the equipment they were connected to. In some cases, 10 people were needed to help bring one person to safety.

A few days later, the hospital’s spokeswoman, Sandra Samper Agrelo, describes the dramatic night. She has come to the hospital to meet with the clean-up team and is visibly exhausted. The mud has been removed from the ground floor, but water still covers the floor of the underground parking garage. But through their hard work, the staff was able to prevent the worst during the night of flooding.

But how did the emergency generators get installed so close to the river in the first place? Samper Agrelo answers, "We just didn’t expect a flood like this.”

Really?

The mood these days in Germany is one of bewilderment and disbelief. District councilors, mayors and residents alike have all been saying that nobody could have expected a disaster this big. Many simply didn’t believe the warnings that the water would reach record levels.

But when you interview climate researchers these days, they rarely say that the situation couldn’t have been predicted.

They have been warning about increasing extreme weather events for years. Meteorologists recorded 2018 as the warmest year in Germany since weather records began in 1881 – followed closely by 2020, 2014 and 2019. Droughts are on the rise, as is heavy rainfall. Things that used to be considered extreme are now deemed normal.

States, cities and municipalities, as well as individuals, will need to prepare for this. So far, the focus has been on reducing greenhouse gas emissions – the target of not allowing average global temperatures to increase by more than 1.5 degrees Celsius, e-mobility, the abolition of short domestic flights, phasing out coal and imposing speed limits.

But there hasn’t been much talk of climate adaptation – meaning how the country can prepare for and protect itself from the worst effects of climate change. For many, the idea of adapting sounded more like surrender. Daniela Jacobs has been witnessing this phenomenon for years. Jacobs is a meteorologist, climate scientist and the head of the Climate Service Center in Hamburg, which was founded by the federal government in 2009 to advise companies and cities on how to adapt to climate change.

"At first, promoting a plan like this was frowned up,” Jacob says She argues that politicians and researchers had worried it would imply to people that they can protect themselves from the consequences of climate change, and that this would "doom” any attempt to embark on measures to protect the climate. It also wasn’t clear to many what was coming, she says. "Many people thought the summer would get a bit warmer and that was it.”

In 2018, Jacob served as one of the lead authors of the IPCC’s Special Report. "The report shows what has already changed irreversibly on the planet – and what we will be facing if there is a 2-degree rise,” she says. She says the report serves as a wake-up call to do more on both fronts. In terms of climate protection, but also in adapting to the changes that can no longer be stopped.

In 2008, the German government published its first, 78-page "German Adaptation Strategy for Climate Change” report. Every five years, a review is conducted to assess what has been implemented so far. According to the federal government, over 180 programs and measures are currently being run to adapt to climate change. But they don’t play much of a role in the public discourse.

The German Insurance Association recently criticized the lack of attention being played to climate-change adaptation in the country. In light of the disastrous flooding, the Helmholtz Center for Environmental Research in Leipzig has called for communities and cities to be better equipped to handle climate change. "It is time, as with climate protection, to launch a large-scale climate adaptation program,” a group of researchers there wrote.

Many German states recently adopted adaptation strategies. The state parliament of North Rhine-Westphalia has passed what it claims is Germany’s first climate adaptation law.

Before the latest moves by states, it had mostly been the local governments’ task to prepare for the new environmental reality. Climate researcher Jacob says a lot is already being accomplished at the local level. But she says it is focused on things like rainwater-retention basins and greening pedestrian zones – in other words, small-scale infrastructure. "That’s not as attention-grabbing as climate protection.”

In Berlin, over 18,300 roofs have now been greened. On the North Sea, coastal German states are building massive dikes for climate change that are higher than the normal ones and, most importantly, wider – up to 130 meters – in order to withstand heavier storm surges.

The residential neighborhood 416 is currently being built in Leipzig, with support from the city’s Helmholtz Center. It includes 2,000 apartments on about 25 hectares with green roofs and green space into which water can seep, as well as troughs and underground water storage. Its goal is to redirect rain, cool temperatures, store water and to be prepared for what is to come.

Read more:

https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/germany-s-new-climate-reality-a-country-races-to-prepare-for-the-unavoidable-a-314326ec-2015-401e-bd00-9e20436034a7

Read from top.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW #########################