Search

Recent comments

- mossad?....

48 min ago - bashing....

57 min 8 sec ago - naked.....

15 hours 44 min ago - darkness....

16 hours 7 min ago - 2019 clean up before the storm....

21 hours 27 min ago - to death....

22 hours 6 min ago - noise....

22 hours 13 min ago - loser....

1 day 53 min ago - relatively....

1 day 1 hour ago - eternally....

1 day 1 hour ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

we agree ....

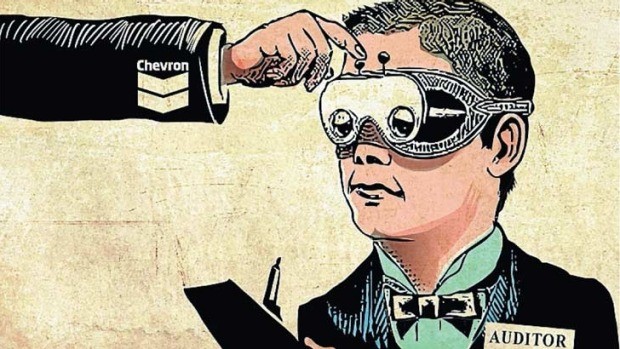

Chevron: A hornswoggler of the highest order

Unlike a Shell, a Caltex or a BP, Chevron is hardly a household name in this country. It soon will be though.

The United States oil giant has splashed a bit of cash among a few charities and community endeavours of late, and you may have noticed big billboards with the moniker, "The Power of Human Energy". That's them.

You are more likely, however, to establish the true nature of a multinational corporation by the things it tries to hide, than the things it tells you. On this basis, Chevron – were it to be honest about itself – ought to refashion its logo to "The Power of Hornswoggling".

The term "to hornswoggle" derives from the nickname of professional dwarf wrestler Dylan Mark Posti, who was skilled in hoodwinking his opponents.

Chevron is no dwarf but it is a past master nonetheless in bamboozling its adversaries, the Australian Taxation Office for instance, which is now mired in a tortuous high-stakes court battle with this slippery corporate character over transfer pricing.

Let's get down to business then.

Chevron sold its $4.6 billion stake in Caltex Australia in March, in the biggest block trade in sharemarket history. It is not getting smaller though; rather it has flipped its downstream petrol business and is slated to emerge as the largest upstream oil and gas player in Australia. Its leviathan oil and gas projects, Gorgon and Wheatstone – $30 billion worth – come on stream later this year and next.

The financial statements for Chevron Australia Holdings, which you can purchase from ASIC at a price, exhibit hornswoggling of the highest order. For start, they report in Australian dollars, which is not Chevron's functional currency but probably helps to ratchet up the cost of related-party loans.

In the manner of the Minerals Council and Deloitte Access Economics, they also conflate taxes with royalties and fail to break down the two, as required by accounting standards, and therefore the Corporations Act.

Yet the piece de resistance is "debt push-down". This is a tactic deployed by many multinationals to load up their subsidiaries in higher-tax countries such as Australia with costs (usually high borrowings) in order to reduce profits – and therefore tax obligations – while siphoning off interest payments on these onerous loans to the parent company.

Chevron is the quintessential culprit when it comes to debt push-down.

The accounts of Chevron Corporation in the US for 2012, 2013 and 2014 show interest expense (after tax) was zero, yes zero. Interest capitalised in 2012 for the whole group was $US242 million. The gross amount of interest paid before tax does not appear to have been disclosed separately.

By comparison, Chevron Australia was charged a total of $975 million (before tax) in 2012. Some of this was capitalised into Australian assets under construction and probably accounts for a large part of the $US242 million.

However, it seems the rest cost Chevron nothing because the value of tax deductions on interest from Australia, and its subsidiaries in other countries to which it has so kindly lent, has exceeded the gross interest Chevron Corp treasury paid to all its third-party lenders and expensed in the income statement.

Chevron appears to be merrily making after-tax net profits from lending to its subsidiaries. Put another way, it is getting foreign taxpayers to pay for its third-party loans. There is $15 billion in related-party loans.

In contrast to Chevron Corp's gearing of 8.2 per cent, the gearing of Chevron Australia is a whacking 60 per cent. Its rival Shell pulls off the same hornswoggle, bulking up its upstream business here, Shell Energy – which also has North West Shelf assets – with debt while its Anglo-Dutch parent has far lower leverage. But it is not even in the same league as Chevron.

With just three days until Treasurer Joe Hockey hands down the federal budget, it is worth reminding retirees and others who stand to have their benefits cut that if hornswogglers such as Chevron paid their fair share of tax in this country, Australia could eliminate the encroaching threat to government revenues from multinational tax avoiders.

It is a good thing the Tax Office urged government this week to improve the transparency regime. If you can't see it, you can't tax it. Corporate regulators, too, could insist on general-purpose accounting, thereby closing down secrecy loopholes.

Arguably, this is already the standard but the big four audit firms favour cosy client engagement over upholding their industry standards.

Besides an array of irregularities in the Chevron accounts, which all conspire for a complete failure in disclosure, and besides the almost $1 billion in interest charges, there are the usual related-party sales. In 2012, those were $1.1 billion, or 38 per cent of all sales.

In the previous year it was 36 per cent. It would be a fair bet that a lot of this was run through the tax haven of Singapore.

There was no detail given on which entities benefit from this, or from which project the income derived.

Then there were the "recharges" in the order of $144 million, service fees perhaps, charged to Australia instead of deducted from dividend income to head office.

The debt push-down is the big one though. Chevron's operation here is toting more debt than Chevron's entire consolidated operations in the US.

Chevron: A hornswoggler of the highest order

- By John Richardson at 17 May 2015 - 8:54am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

remember this...?

http://www.yourdemocracy.net.au/drupal/node/27261

a serial offender ...

Yes Gus.

Sadly it seems that the likes of Chevron can 'dry-gulch' the world with impunity.

Somewhat ironic that the warrior princes in that 'remote place' called Canberra can quickly muscle-up to threaten the lives of a couple of miscreant pooches for breaches of our quarantime regulations but can only wring their hands in faux desperation in the face of the gangsters from Delaware.

Is it really any wonder that corporations believe that they can thumb their noses at anyone who might have the temerity to challenge their racketeering?

Have a good one.

Cheers,

John.

too late she cried ....

Secretive oil major Chevron Corp has taken the art of tax avoidance to its ultimate form thanks to a scheme so aggressive that it goes beyond merely reducing exposure to income tax, but rather, has been designed to make a profit from the Australian Tax Office.

These are the findings of a report, commissioned by unions in the United States and obtained by Fairfax Media, that describes Chevron's Australian arrangements as "a sham".

By exploiting loopholes to claim tax relief on "artificially created interest payments", Chevron has "actually profited from the act of borrowing money at the expense of Australian taxpayers. It goes beyond any commercial objective of providing debt finance leverage to the point where the value of its tax benefits from interest deductions exceeds the actual before-tax cost of the loan".

Chevron Australia declined to respond to detailed questions about the scheme. The report into its tax affairs is yet to be made public.

The ATO is already locked in a landmark lawsuit against Chevron in the Federal Court where it is seeking to retrieve $322 million with penalties. The case alleges Chevron spun out a complex corporate structure for the explicit purpose of avoiding $258 million in Australian taxes between 2004 and 2008.

It created a US subsidiary of its Australian company in the state of Delaware, a tax haven, and which borrowed $2.45 billion at an initial interest rate of 1.2 per cent and then on-lent the money to an Australian entity at an interest rate of 9 per cent. This structure may have netted Chevron up to $862 million in tax-free dividends during five years.

However, the Tax Office case is contained to attacking the margin above the base interest rate as being not at arm's length. It is a transfer-pricing case. The union report says the ATO has failed to challenge the broader issues of tax avoidance for a transaction intended to make a profit at taxpayers' expense – a potential case under Part IVA of the tax laws that requires that the "dominant purpose" of a transaction be commercial rather than tax driven.

Interest on the loan in question, says the report, should not be used to finance the distribution of capital created out of a revaluation of assets.

The scheme kicked off in 2003 when Chevron Corp (CVX) Treasury set up a special purpose vehicle known as Chevron Funding Corporation (CFC) in Delaware. This company, wholly owned by Chevron Australia Holdings Pty Ltd (CAHPL) issued $US denominated commercial paper into the US market at rates as low as 1.2 per cent. The initial offerings and rollovers were managed for CFC by another CVX subsidiary. CFC on-lent funds from the commercial paper program to CAHPL.

"The CFC-CAHPL loan was made in several tranches under a Credit Facility Agreement (CFA). However, despite having raised funds in $US, all CFA advances were denominated and repayable in $A," says the report. "The $A interest rate was set at $A-LIBOR plus a margin of 4.14 per cent. Over the term of the loan the effective interest rates ranged from 8.8 per cent to 10.5 per cent. CAHPL claimed tax deductions on the interest it paid to CFC, giving it tax relief at the rate of 30 per cent. These interest payments were exempt from withholding tax."

CFC, says the report, supposedly took the exchange and interest rate risks on the CFA, but made a "substantial and entirely fictitious margin". The $US currency risk remained with CAHPL because it wholly owned CFC. CFC paid interest in $US on its commercial paper program but was not liable for tax on the margin it made. "Instead, it was able to pay its fictional tax-free profit back to CAHPL as a monthly dividend. The dividends were exempt from US withholding tax and were treated as non-assessable, non-exempt income for Australian tax purposes."

That is, no tax was paid in Australia or the US on the dividends declared by CFC and received by CAHPL. The result of these arrangements was that CAHPL claimed a 30 per cent tax relief for the interest paid at rates of up to 10.5 per cent, despite the fact that the net cost of debt was as low as 1.2 per cent.

The annual meeting for the company looms and directors are likely to come under fire for this and other transactions. As is increasingly the case with multinational companies, it appears that the decision-making has been centralised in the global headquarters and Chevron executives in the US are arguably shadow directors of the Australian operations.

Chevron parents leave ATO an orphan