Search

Recent comments

- wrong target....

1 hour 57 min ago - aerosols....

2 hours 16 min ago - middle powers....

2 hours 37 min ago - disgraceful....

3 hours 36 min ago - bets on war....

4 hours 2 min ago - graham's crap....

7 hours 3 sec ago - hypocrisy....

7 hours 21 min ago - blinded....

7 hours 52 min ago - falling for the US propaganda....

8 hours 18 min ago - MbS calls china...

9 hours 6 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

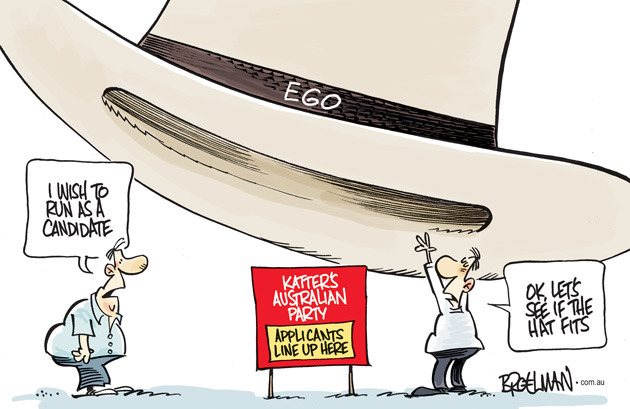

the bigger the hat, the smaller the herd .....

Bob Katter wants to dominate the electoral map, but according to former insiders the maverick federal MP has an abrasive way of carving out his party in his own image.

Former national general secretary Bernard Gaynor reveals that when Katter was dividing his fledgling political party into geographic zones after last year's Queensland election, he simply used a whiteboard marker to draw lines on a laminated map of the state.

The problem, Gaynor says, was that these lines did not match up with electorate boundaries - making it hard to tell some party members what zone they were in.

''I wasn't allowed to change the zones,'' Gaynor says, as an example of how Katter's Australian Party operates as a ''one man band''.

It's an insight into the behind-the-scenes difficulties the party has had as it attempts to prepare for its first federal election outing where it aims to run candidates in every seat.

Damaging internal brawls over gay rights have observers wondering whether the party - part-protectionist, part-populist - is about to make serious inroads or implode ahead of the September 14 poll.

Apart from bruising public disputes over whether the marriage law should be changed and how ''tolerant'' the party should be on social issues, there are questions over whether a party structure is compatible with Katter's style.

Party officials are not always sure what Katter will say when he fronts a media conference. But national director Aidan McLindon brushes off the stories about the party spinning out of control.

McLindon briefly served as a Liberal National Party state MP in Queensland, having outpolled independent challenger Pauline Hanson when she attempted her political revival in 2009. Now influential in Katter's Australian Party, McLindon suggests any publicity is good publicity. ''Yeah, OK, we've had a bit of a domestic that spilled into the public arena; all parties do that … and particularly new ones,'' he says.

While political experts say it is always difficult for new minor parties to get elected, Katter's Australian Party could be competitive in numerous Senate races, particularly in Queensland. Queensland University of Technology professor in political science Clive Bean says that while Katter's profile is strongest in Queensland, he also has appeal around the nation.

Professor Bean, an expert in voting behaviour, says the electoral system makes it ''extremely hard'' for minor parties to gain a foothold in the House of Representatives, but chances are better in the Senate, where quotas allow candidates with lower support to clinch seats.

A lot would depend on preference deals. Labor is rumoured to be considering preferencing Katter's Australian Party over the Liberal National Party in Queensland.

And in recent weeks leaked discussion papers from the Coalition have been big on regional development - with ideas such as building new dams and using incentives to lure people to northern Australia. The make-up of the Senate is important because it will determine whether a Coalition government would be able to pass legislation through both houses.

Regardless of how many seats Katter's Australian Party ends up winning, McLindon says its real power comes through its ability to do preference deals with the major parties and its influence on who wins government.

There's no doubt that Katter's Australian Party - which gathered for a management meeting on Friday - has appeared increasingly erratic in recent weeks. In early January, Katter was talking about fielding candidates in 70 or 80 House of Representatives seats. The next day he vowed to run in all 150 electorates.

McLindon initially dismissed comments by two potential candidates against gay rights as a ''storm in a tea cup''. By the afternoon he declared one had withdrawn her candidacy and the other had been suspended.

Early this month, Katter endorsed theatre director Steven Bailey to run for the Senate in the ACT. McLindon, acting on orders of the party president, Max Menzel, soon asked Bailey to resign because the budding politician had voiced his support for same-sex marriage.

But Katter insisted Bailey should remain as the candidate.

Katter, the long-serving member for Kennedy in North Queensland, has tried to shift the focus away from the gay rights issue, saying candidates should focus on the key issues such as the market share of Woolworths and Coles, foreign ownership and regulating the dairy industry to better support farmers.

''If you're preoccupied by this in our party, we throw you out - we've established that,'' Katter tells Fairfax Media of the gay rights issue.

''We don't think about it. We don't discuss it. You're preoccupied with it. You have a problem with it. We don't. It's not on our agenda.''

Gaynor, a Queensland Senate nominee who was suspended by the party last month after tweeting that he would not let gay teachers educate his children, says Katter doesn't want to alienate potential voters but he is dealing badly with the gay rights issue.

''Bob is great TV when anyone asks him about gay marriage and he doesn't understand that. He thinks, 'If I don't talk about it, people will stop talking about it', but it draws people to ask the question more,'' Gaynor says.

Gaynor is indicative of the conservative base of the party which wants to stand by one of its stated core values that marriage should remain between a man and a woman.

But others want to project a more moderate image.

Peter Pyke, a former Labor MP who was an eager early member of Katter's Australian Party, was among a small group of ''concerned party members'' who called for civil unions to be supported as an alternative to gay marriage.

The group included the party's then president, Rowell Walton, and former Queensland campaign director Luke Shaw, who gained notoriety as the jury foreman in former National Party premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen's 1991 perjury trial. The jury failed to reach a verdict. It was later revealed that Shaw was a member of the Young Nationals.

The civil union motions were greeted with scorn by some members and Pyke, who was leading the internal push for reform, says he was forced out. More recently, former state election candidate Darren Hunt quit the party, claiming it had not done enough to shed its homophobic image, and another, Terri Bell, denounced the management team as a ''boys' club''.

Gaynor, who tried to fight his suspension, says Katter should stop getting involved in every decision the party makes if it is to be successful in the long term.

Katter's chief of staff, Elise Nucifora, emailed members on Thursday to allay concerns about the damaging ''internal party matters'' attracting publicity, insisting it was not on the verge of collapse. Katter will speak with all of his party's zone representatives throughout the next few weeks ''to provide inspiration and direction''.

According to McLindon, the party has about 3000 members, with 100 new ones signing up each month, and it has lined up candidates for 17 out of the 30 seats in Queensland.

It has received a total of 140 applications for Senate and lower house candidates across the nation - including ''a lot'' from New South Wales and Victoria.

As Katter's Australian Party tries to extend its electoral foothold beyond Queensland, potential rivals insist they're prepared for a spirited fight. Northern Territory Country Liberal senator Nigel Scullion says he's ready to ''take off the gloves'' if a Katter candidate takes him on.

''I don't think the very small following KAP may have does anything outside of North Queensland. Clearly, that's why we have the K in KAP. It's the bloke in the hat; he's well known; he's like everyone's granddad,'' Scullion says.

Katter says he is confident of gaining multiple Senate seats, including seats outside Queensland, but stresses the need to put internal stumbles behind the party.

''We've got to be careful - we've had a couple of grenades go off in our hands so we've got to be a bit careful with candidates.''

- By John Richardson at 18 Feb 2013 - 11:11pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

a magic man in a magic land .....

One steamy Saturday morning in mid March, Bob Katter, dressed in jeans, a pale shirt and his trademark cream-coloured Akubra Arena, was pacing up and down outside a home in Emerald Creek, 15 minutes’ drive from the town of Mareeba, in Far North Queensland. The house’s garden was a stunning tropical display of palms, ferns, creepers and bright-pink bougainvillea. Around it were farms growing coffee, capsicums, mangoes, avocadoes and sugarcane. But Katter looked nervous. Today was D-day, when locals would decide whether to secede from the Tablelands Regional Council, a super-shire imposed on them only five years before, by the then Labor state government. The garlanded house was doubling as a polling booth. Under a large canopy, the “Vote Yes” team, comprising a revolving party of locals, watched their restless federal member enthusiastically greet the trickle of constituents with how-to-vote cards.

Katter’s electorate of Kennedy stretches from the Great Barrier Reef to the Northern Territory border. It is the third largest in the country, which may go some way to explaining why Mareeba’s 10,000 locals, whose state representatives are based some 1400 km to the south in Brisbane, object to having their local government outsourced. The voters all recognised Katter, who nonetheless introduced himself as “Bobby Katter”. In between talking to them, he patrolled the roadside, yammering on his mobile.

A local newspaper had pronounced that the vote “may well be the most important political decision the people of Mareeba make”. The issue had divided locals. Polls indicated that 42% of them wanted Mareeba to go it alone, 34% preferred the status quo and nearly one in four remained undecided. The Queensland government had warned that de-amalgamation would cost more than $8 million and amount to large rate rises.

Beneath the sun shelter, someone reported that down in Kuranda, a rainforested tourism hub derided in Mareeba as a place for hippies and tree-huggers, a woman had torn up a “yes” card and thrown it back in a campaigner’s face. Nobody was handing out anything but “yes” cards here. Anyone wishing to vote “no” in Emerald Creek was using the side entrance. Katter had a lot riding on a majority “yes” vote. It would be more than a vote for de-amalgamation; it would be a validation of his core political principles.

Inner-city dwellers like to reduce Bob Katter to a caricature: the ignorant country bloke, pining for the values of a past era. Yet there is a raw appeal in his refusal, unlike Julia Gillard or Tony Abbott, to resort to weasel words or hide his true beliefs. More than that, come July 2014, it is just possible that his Katter’s Australian Party (KAP) will hold the balance of power in the Senate.

Ahead of meeting Katter in Sydney, a few days before the Mareeba vote, I tried to buy his book, An Incredible Race of People: A passionate history of Australia, in local bookshops. My enquiries were met with condescending smirks. I did find copies of Kattertonia: The wit and wisdom of Bob Katter, a slim volume mocking his more outrageous statements – “I would walk to Bourke backwards if the poof population of north Queensland is any more than 0.001%” – and goofy homilies – “We are all actors on a fleeting stage, as a famous man once said.”

I met Katter in the lobby cafe of the five-star Sheraton on the Park hotel. The cafe was packed with businessmen and women. As I’d been warned was likely, he was late, so I settled down to read An Incredible Race of People, which I’d finally found en route. It’s a quirky history of Australia, filled with folksy anecdotes, potted biographies, blizzards of statistics and a relentlessly subjective take on who and what made Australia great. Some businessmen suddenly turned towards the foyer; Katter had arrived. He looked as if he had just come from the cattle sales. Accompanied by his assistant chief of staff, he took off his hat, bowed slightly to the waitress and sat down.

Katter’s hair is silver, and, despite being 67, he has a surprisingly wrinkle-free face. Perhaps it’s because of the hat. He spoke in a soft, raspy voice. From his media appearances, I thought his default expression would be a sneer – what models used to call the Who farted? look. In person, this wasn’t apparent, though any mention of intellectuals or “trendies” from Melbourne brought it on.

At first he was extremely difficult to talk to. Many answers to my questions came almost word for word from his book. Other replies were so discursive I had trouble following them. I wondered if, as a Catholic, he believed in original sin. “It’s like that film 2001 …” he began, before trailing off. Queried about his respect for Ned Kelly, he said that the bushranger summed up the great Australian ethos of mateship: “A man would have to be a dingo to run out on his mates.” Then he burst into a song chorus that went, “You’re the son of a son of a scoundrel like me.”

After he sang a reply to another of my questions, I figured this was all for show. I asked if he had constructed a character especially for the media. He shook his head, a little irritated. I showed him Kattertonia, with its cover photograph featuring him jabbing his finger at the reader, his face screwed up and demented-looking. He paled and licked his lips. “I’ve heard about this,” he said quietly, looking away. “I haven’t read it, though some of my staff say it’s just a funny book.”

As his ever-patient assistant chief of staff flitted in and out, reminding him of a radio interview he had scheduled, he relaxed and his answers became less evasive. By the time he left to go on air, I was still wondering whether the Katter presented to the public was real. But delving further into his book, I became less sceptical. Katter takes seriously those topics that had bored me when I studied Australian history at school. It is a book of heroes in the story of Australia’s development.

Those he reveres include Edward “Red Ted” Theodore, a socialist and financial genius who became the federal treasurer during the Great Depression; coal titans such as Les Thiess; Country Party leader John McEwen, who pushed for tariffs and protection for the manufacturing industry; and the postwar prime minister, Ben Chifley, who increased immigration and kick-started the Snowy Mountains Scheme. Katter regards history as being dictated not so much by grand ideological movements as by the character or lack of character of the men involved. His giants pushed ahead with their grandiose schemes even when everyone doubted them. Seeing them through Katter’s eyes, I realised I had always taken their significance in the development of the nation for granted.

Three days later I flew north, to Cairns, to seek out Katter on his home turf. Before taking a bus to Mareeba for the next day’s de-amalgamation vote, I visited the Cairns museum. A guide there told me how she had once attended a debutante ball in Julia Creek, an outback cattle town in the dry heart of the far north. There were four debutantes, ranging in age from 13 to 78. Katter drove 1000 km there and back from his home in Charters Towers, inland from Townsville, to be there that night. Though no supporter of his, she couldn’t help but be impressed.

The countryside of Mareeba, an hour’s drive from Cairns, is fertile table-land. The town’s wealth had been based on growing tobacco, until economic rationalism levelled that industry in the 1990s. The area now markets itself as a fruit bowl, but the town is suffering. Outside Coles, a teenager wearing headphones and bobbing to a rap song was shouting out, “Motherfucking bitches like you!”. Further down the street stoned black and white teenagers giggled and jostled one another.

Later that evening I went to the Leagues Club. Small and crowded with families, with pokies, Keno, cheap food and huge plasma screens tuned to sport, it was more popular than the hotels on the main street. A woman in her 70s was wearing a Yes T-shirt. Her name was Irene and she owned the local bookshop. She handed me a leaflet claiming that since amalgamating with the shires to the south, Mareeba had suffered from a culture of “intimidation, bullying and coercion”. Everyone I talked to seemed intent on voting yes, except for one man who sidled up to me to impart that, unfortunately, Bob Katter was a simple man who had been caught up in a conspiracy. “A conspiracy of what?” I asked. “Why, to turn this place into Little Italy,” he said, as if I should have known.

Katter’s staff had arranged for us to meet the next morning at Vincenzo’s Coffee Lounge, halfway along the main street. It was only nine but the sun was already baking hot. The cafe was in the centre of a small shopping complex – Katter, like any astute politician, wants to be seen. He arrived late, as usual, and ordered a huge breakfast. Though I told him I had already eaten, he ordered me some raisin toast anyway. Katter greeted the staff but got their names wrong and seemed miffed when this was pointed out. He prides himself on his recall of people’s names.

He sprinkled so much salt and pepper on his eggs and sausages that I feared for his health. Our talk was frequently interrupted when Katter hailed someone he recognised or people came up and introduced themselves. Katter has a tireless capacity for connecting with people and listens to their ideas and complaints with genuine interest. At the same time it’s clear he revels in the attention: his body straightens; his face lights up.

When Katter talks about his politics, especially his support for unions and the protection of Australian jobs and industry, he sounds like an old-fashioned Labor man, which, in a way, he is. His father and grandfather had been members of the Labor Party. When it split in 1955, it was, as Katter says, “as if my father’s soul and spirit had been grievously wounded”.

His father joined the Democratic Labor Party in 1957 and then later the Country Party, for which he won the federal seat of Kennedy in 1966. Katter senior was a combative and self-righteous man, not given to introspection, who preferred Canberra to home. Bob Katter’s beloved mother was left to raise him, his brother and sister in the barren mining and cattle town of Cloncurry, east of Mount Isa. I got the sense Katter never forgave his father for his mother’s loneliness; there were rumours of Katter senior’s womanising down south before his wife’s death in 1971. His father’s constant absences meant that Katter was brought up in what he calls a “matriarchy”. He seems to trust women more than men and it’s noticeable that most of his staff are women.

Katter’s family was relatively well off in Cloncurry. His parents owned a clothing store and leased the local picture theatre. Of the 60 kids his age, he was one of only six who finished Year 12. There were high hopes for him to further his education but he dropped out of university. He likes to pretend that it was probably a good thing he didn’t “intellectually prostitute” himself, describing university graduates “as a sort of herd of brainless bison stampeding across the prairies”.

He worked at the family’s store and at night ran the picture theatre. The movies affected him, adding a Technicolor gloss and a sense of Hollywood heroics to his vision of the world. In conversation he’ll expand on a story by saying, “Now we go to scene two.” He adores films like Ben-Hur, Braveheart and Robin Hood, perhaps because they confirm his thesis that an individual can change the course of history. The young Katter became a prospector, was an infantry instructor for seven years, and invested in cattle and mining before being elected to state parliament in 1974. He went on to become a minister in Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s government until its fall in 1989. In 1992 he switched to federal parliament, winning his father’s old seat of Kennedy for the National Party, before turning independent in 2001.

Independence suits him; like his heroes, he wants to be his own boss. He has little respect for “pygmies”, as he calls his political contemporaries. In his view, a tertiary education can’t teach you what hard manual labour can, which is an understanding of the problems of the working man. That’s what he admired about Bjelke-Petersen, he told me: 13 members of his cabinet had worked in the canefields.

Katter must have enunciated his vision for Australia thousands of times but his enthusiasm makes it still sound off-the-cuff. He frequently goes off on tangents. Without any prompting from me, for instance, he railed against gun control, blaming the massacres at Port Arthur and Hoddle Street on the limitations of psychiatric care. “People knew these men were crazy. If only psychologists and psychiatrists can report them to the police before they kill, then they could be stopped.” Asked if this applied to Catholic confession, he paused, considered this for a moment, dismissed it with a nod and then jumped to another topic. This happened again and again: if the subject made him uncomfortable – homosexuality, say – or fresh facts didn’t back his position, he’d pause and his eyes would glaze over. Attention to detail, his staff will concede, is not one of his strengths. At one point I asked him about the infiltration of drugs in country life, as testified to by the local drug-squad chief in the news that morning: meth labs were becoming prevalent in rural towns. Katter’s eyes became distant. I could see he wasn’t being deliberately evasive, it was just that such an issue bewildered him. His world view is simple and straightforward; the complexity of modern life just muddies things.

His understanding of life outside Australia, too, is narrow. He shows no interest in foreign affairs and has been overseas just once, to Brazil and the United States to investigate the potential of the ethanol industry. Correspondingly, the KAP is not exactly a worldly outfit. Katter talked about one of his “biggest mistakes”: his decision to approve a homophobic advertisement for his party’s Queensland election campaign last year. On the one hand he blamed himself for not paying enough attention to the ad or foreseeing its consequences, but on the other added that he wasn’t in control of such matters. This lack of discipline runs through the party, which has seen several candidates reprimanded for making blatantly homophobic and bigoted comments. One candidate, a doctor, went to court for chain-sawing down ALP electoral signs. Like Pauline Hanson’s One Nation party before it, the KAP attracts ratbags, the undistinguished and the plain daffy. Evidently, the KAP’s selection process lacks rigour. Katter doesn’t seem to be strongly in charge of his own party but, more than that, he doesn’t seem to care particularly that he’s not. He loathes having to spend time in Canberra, and acknowledges that he’s not sure he has the stamina for the constant deal-making that would be required should his party achieve the balance of power. “I’m a sprinter, not a marathon runner,” he told me. This lack of discipline seems a serious disability in light of the spectacular implosions of Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s push for Canberra in 1987 and Pauline Hanson’s One Nation party, both of which were ultimately due to the woeful quality of the candidates. I put to Katter that there was a serious risk his party could go the same way. “I’m aware of that,” he said soberly. “Very aware.”

What would the KAP be without Katter? “Well,” he beamed, “Gaullism survived the death of de Gaulle.” But what is Katterism? And is his only son (he also has four daughters), Rob Katter, likely to take over? Katter junior won his father’s former state seat of Mount Isa in 2012, and is one of three KAP representatives in the Queensland parliament. But Rob Katter has previously expressed misgivings about politics, partly out of knowing all too sorely its demands on a father’s time. Also, growing up in the domineering presence of his flamboyant father can’t have been easy: the son has such an understated, diffident manner that you wonder if his political commitment is more a rite of passage than a passion. His few speeches are hollow echoes of his father’s ideas and his parliamentary attendance is haphazard at best. Although Katter says he thinks his family’s political legacy will continue with his son, he must have noticed my dubious expression because he rushed to add that he’d told Rob if his heart wasn’t in it, he should quit. Few would be surprised if this happened.

Before meeting Katter I’d rung a couple of journalists who had spent time with him over the years, asking for their impressions. Their replies were alike – Katter was pleasant if chaotic company, had a mind stuffed with facts and was a shrewd media operator. His nickname among his staff was “Cyclone Bob”. My friends, though, all wanted to know the same thing: was he mad? I asked him this straight out. There was a pause, his eyes glazed over, he bit his lip and promptly changed the subject. Then he veered right back. “You know, I am a boofhead. I am a clown, but intellectuals underestimate me at their peril.”

The Labor and Coalition parties don’t – not any more. In Queensland especially, Katter’s appeal to what he calls “the new working class” has made the two major parties nervous. His policy of curbing the numbers of foreign workers allowed into the country has won support from both unions and conservatives, and was doubtless a factor in Julia Gillard’s recent strong rhetoric about cutting back temporary foreign-worker intakes under the 457 visa program. At the same time, the Coalition has leaked discussion papers flagging massive infrastructure projects (100 dams) as well as a special economic zone for the far north, in an apparent attempt to steal Katter’s thunder. Though the plans were ruthlessly derided as grandiose developmentalism in the southern press, up north they got a favourable run for weeks.

Then there’s Katter’s hostility to the Coles and Woolworths duopoly, and the way the two companies crush small farmers by pushing suppliers’ profits down and buying produce cheaply from overseas. Katter blames them, in part and indirectly, for the high rates of suicide among Australian farmers. The issue has percolated south and both political parties know they need to tackle it – Katter’s stance is deeply popular in the bush.

Suicide is a persistent preoccupation of Katter’s. When the federal government declared the rainforests of north Queensland a World Heritage Area in the late 1980s, hundreds of timber workers, including many Aboriginal men, lost their jobs. At Yarrabah, a former Aboriginal mission south of Cairns, the suicide rate leapt to one of the highest in the land – proof, in Katter’s eyes, of his oft-stated view that bureaucrats and regulations are literally killing people. He’s genuinely horrified that rural people are constantly being forced to the edge of madness.

I got a taste of this despair at the Emerald Creek polling booth. The anger and frustration among the voters was palpable. Electricity prices had doubled in the past year and aquaculture farmers could no longer afford to run their businesses. A gnarled, bearded eel farmer told me he was moving his business to Indonesia. Prawn and barramundi farmers were exporting their know-how to Thailand and Malaysia. What galls these men is that the government doesn’t seem to care to keep these industries in Australia, producing Australian food for Australian people. Instead it lets cheap imports flood the market.

Katter understands this sense of hopelessness. He knows that the high Australian dollar is partly to blame for squeezing farmers financially. At the polling booth several farmers said the dollar should be devalued to 50 US cents. Katter countered that 70 cents was about right. What was needed were visionary leaders, like those of the 1950s, who would open up the north, turn back the rivers, build dams, stimulate development, protect manufacturing and agriculture, and strengthen the unions. But Katter’s dream for his “magic land” is about more than job creation or the north becoming Australia’s food basket. It’s rooted in his fear that we must populate the area or perish. For him and his supporters the truism holds that “a people without land will look for a land without people”.

He likes to call north Queenslanders “our mob”. The multicultural make-up of voters at Emerald Creek is extraordinary: a genetic jigsaw of Anglos, Italians, Germans, Pacific Islanders and Aboriginal people. The last are a crucial component of Katter’s “mob”; in our time together he seemed curiously reluctant to discuss his Lebanese lineage but would talk dreamily of finding out one day that he had Aboriginal connections. Katter’s empathy with Aboriginal people dates back to his father, who ended segregation in his Cloncurry cinema. Katter despairs of the way they are treated and is appalled by the land-title arrangements of Aboriginal lands and communities, which preclude private ownership.

Yet his practised ease with his supporters is not entirely natural. As one of the more well-off kids in Cloncurry – he had shoes, for one thing – he knows what it’s like to be thought of as stuck-up. Although you can get away electorally with looking like a wanker in, say, Adelaide, it spells instant political death in Katter’s part of the world. He freely admits he is extremely conscious of the tall poppy syndrome, which is why, for example, he always flies economy class.

Then there’s his drinking, or lack of it. When I asked him why he was a teetotaller, he joked how it made him a sharper fighter. He then told me a story about how he used to drink rum and milk until one day he woke up to find that the night before he had agreed to buy a half million–acre property. I suspect it’s more complicated than that; perhaps alcohol brought out aspects in his personality he didn’t like. Regardless, it makes him the odd man out among his hard-drinking “mob”, which means he has to work all the harder to be seen as a man of the people. It also reinforced my steadily growing sense that Katter is essentially a loner. He’s never still, even when not travelling. In conversation and in crowds, he’s hyperactive, promiscuous with his handshake and constantly rattling off streams of anecdotes and statistics. Life is all action; even if there were time for reflection or introspection, you get the sense he’d rather be on the move.

At Emerald Creek, he wasn’t sticking around for the election result, either. He was heading home, to Charters Towers. He shook hands with the dozen or so people around the booth, strode off and then, almost as if he had forgotten something, turned around and shouted triumphantly, “Youse are doing a great job for your country!” Then he took off his hat, got in the car and sped off.

I went to the Leagues Club again that night. The “Yes” supporters had booked a side room. At 8.20 pm there were whistles and screams of delight. The vote was 60% in their favour. It was, in essence, a community cri de coeur against being made invisible by the bureaucratic apparatus of government. Mareeba would once again have the greater say in the running of Mareeba. But it was more than that. They had reversed change. They had turned back time – well, at least to before 2008. To others this might seem a backwards step, but to Katter and his mob in the north, as William Faulkner said of the American south, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Louis Nowra is an author, screenwriter and playwright. His books include Ice and The Twelfth of Never, and he is co-winner of the 2009 NSW Premier’s Script Writing Award for First Australians.The Heart & Mind of Bob Katter - Adventures In Katterland