Search

Recent comments

- dumb blonde....

7 hours 21 min ago - unhealthy USA....

7 hours 55 min ago - it's time....

8 hours 17 min ago - pissing dick....

8 hours 35 min ago - landings.....

8 hours 47 min ago - sicko....

21 hours 35 min ago - brink...

21 hours 52 min ago - gigafactory.....

23 hours 38 min ago - military heat....

1 day 21 min ago - arseholic....

1 day 5 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

the awstraylen solution .....

There was a Pacific Solution, a Malaysia Solution and, fleetingly, until someone thought to ask the Timorese, an East Timor Solution. But what exactly is the problem? I’m not asking rhetorically. It’s a serious question, perhaps the most serious question in the entire debate surrounding asylum seekers arriving by boat, and yet it is barely asked. The axioms of the public conversation simply hold that asylum seekers on boats are a problem and that their existence should cease. At the same time, all protagonists sagely concede the problem is devilishly complex.

Yet the repetition of such mantras conceals the fundamental question: what, precisely, is the problem we are trying to solve? Stopping the boats, sure, but why? Is it the nature of the journey that concerns us, or the fact that the boats often arrive on our territory? The difference is essential. These are opposite concerns, present opposite problems, and invite opposite solutions. One approach is about protecting the rights and wellbeing of asylum seekers; the other is about protecting ourselves.

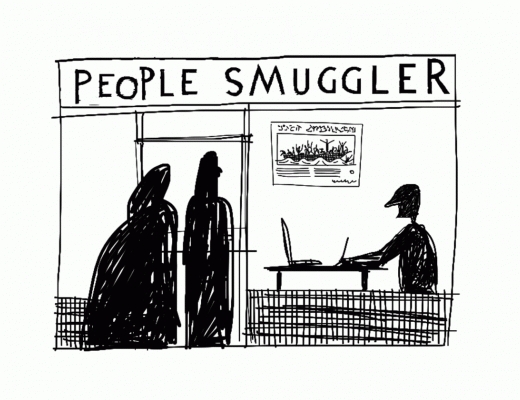

The unvarnished rhetoric of the Howard government railed at the asylum seekers themselves; it cast doubt on their credentials, insinuated they might be terrorists and painted them as unworthy of residency for their (invented) preparedness to throw their children overboard. Today’s debate, by contrast, focuses on people smugglers as the chief villains. Ever since Kevin Rudd as prime minister declared them “the vilest form of human life” who should “rot in hell”, people smugglers have become the proxy objects of our discomfort. Time, and a series of tragic events at sea, have now delivered us to a point where debate proceeds on the basis, real or feigned, of compassionate concern for the fate of asylum seekers. Even the Coalition has generally played along, the odd clumsy attempt at a Howard-era gesture notwithstanding, such as Tony Abbott’s recent declaration that boat people were “un-Christian” for queue jumping.

It seems the boat people must be stopped not for our sake, but for their own. This does not make our policy suggestions any less brutal – indeed, it may make them more so. It means even the most apparently harsh or punitive policy is recast as ultimately fair and benevolent. If it means we send people to Malaysia, beyond our jurisdiction and certainly beyond our care, relying on nothing more than a non-binding arrangement to protect their human rights despite Malaysia’s ghastly form in dealing with refugees, it is because mercy demands it. Similarly we justify sending people to what we can now uncontroversially call factories of mental illness in Nauru.

Such policies necessarily rely on the logic of deterrence. Languishing in Indonesia or elsewhere, with minimal hope of resettlement, asylum seekers get on boats aware that they may die. We can only deter them by manufacturing something even more hope-destroying. Such calculations are never made explicit, but they are central to this kind of policy making. Stripped of bureaucratic language, this is precisely the government’s argument against re-opening Nauru: it’s not horrible enough.

The current debate presumes there is no less brutal way to stop people smuggling, and thus prevent the loss of life at sea. But this is not true. We could, for instance, significantly increase our refugee intake from Indonesia. Many people who get on boats have already joined a queue, been processed by the UNHCR and been assessed as refugees. What they haven’t been is resettled. Indonesia harbours a large backlog of people going nowhere – around 10,000 of them.

So far this year we’ve resettled around 60 refugees from Indonesia directly. If the annual figure were, say, 6000 (which would doubtless help Australia achieve more meaningful co-operation with Indonesia on surveillance, processing and policing), the number of boats would decrease rapidly and no one would need to be mentally destroyed in the process. More asylum seekers might pour into Indonesia, but their prospects within the queue would no longer be hopeless; they would surely be less likely to risk their lives on leaky boats.

After all, we could absorb several times that annual number with barely a blip. We could make the humanitarian intake 100,000 if necessary, and we’d cope just fine. This would do more than break what the government likes to call “the people smugglers’ business model”. It would take away their clients altogether.

This will not happen. Not because it wouldn’t work, but because it wouldn’t work in the way we want. For all the gnashing of teeth and demonstrative compassion, our politicians have greater concerns than the lost lives of a few hundred asylum seekers. They have political equations to balance and shibboleths to repeat.

This is true even of the Greens, whose position is most explicitly about the rights of asylum seekers. One of the more intriguing manoeuvres of the last parliamentary sitting week before the winter recess was the Coalition’s offer to increase the refugee intake by 6000 to 20,000 per year and limit processing times to 12 months. This responded to the problem directly and reflected much of the Greens’ own policy, but it came with a catch: offshore processing in Nauru – an unthinkable backdown for the Greens’ constituency. Consequently, Australia continues to process and detain asylum seekers onshore – which, let us remember, remains brutalising – at the expense of thousands more people who continue to languish, and unknown others who will perish at sea. Apparently, asylum seekers’ human rights must be protected, even if it kills them.

But the crocodile tears fall heaviest from the eyes of the major parties. For them, their ostensible fellow-feeling notwithstanding, the problem remains a question of sovereignty and security, of demonstrating their capacity to keep the

boats out, because they understand the hostility in the electorate towards asylum seekers. We must not simply stop the boats, we must deny access. We must create the illusion of a secure fortress, girt by a moat. Hence the invincible requirement to send the boat people elsewhere. The Coalition simply must have Nauru; the government must have Malaysia. The former knows the benefits of fortress politics and has long practised it. Meanwhile the latter wants to act in the interests of asylum seekers and simultaneously look like it is not – a confusion apparent ever since Kim Beazley failed to contest the Howard government’s contrived “children overboard” accusations days before the 2001 election, and further spelt out once in government by Kevin Rudd’s “hardline and humane” approach.

For all the rhetorical realignment, we are stuck with the perpetual division in asylum-seeker policy between those who prioritise the rights of asylum seekers and those who see them as some kind of threat. If that chasm is camouflaged, it is for one simple reason: that however much our politicians want to protect asylum seekers, or protect the nation that so bizarrely fears them, they want most of all to protect themselves.

- By John Richardson at 8 Aug 2012 - 7:09pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

from father brennan...

There is an ethical way to stop the boats and prevent deaths at seaFrank Brennan

ABC RELIGION AND ETHICS

20 AUG 2012

Behind all the legal technicalities and political argument about boat people, there is room for deeper ethical reflection and a more principled proposal. But first, to clear away some of the debris.

Last week, the Australian Parliament led by a government in panic mode legislated to do three things: lock the courts as far as possible out of reviewing government decisions about offshore processing; set the course for re-instituting the Pacific solution in Nauru and Manus Island; and delay any prospect of a Malaysia agreement until after the next election - which probably means never.

A brief word on each of these three matters:

We need another proposal which could pass ethical muster as well as being workable, given the Parliament's newfound bipartisan hostility to onshore processing.

Why the Pacific Solution Mark II is unethical

Within the international order, the security, well-being and human rights of persons is primarily the responsibility of the nation state. The community of nations respects the sovereignty of nation states.

It is to be expected that some persons will face persecution at the hands of their own governments because the government is either wielding the discriminatory fist or holding its hands behind its back while others engage in the persecution. Thus the international community has a responsibility to look to the security, well-being and human rights of those who are so persecuted.

Those fleeing persecution should be treated in a dignified manner, being offered basic protection. They should be humanely housed, have their claims dealt with under a transparent, fair process and be offered a durable solution in a timely fashion. Those fleeing persecution should not view their plight as the basis for seeking their preferred migration outcome. Once offered an appropriate level of protection, they should await local integration into their host community or resettlement in a third country.

Ideally, each nation state should process onshore the asylum seekers arriving in its territory. Alternatively, nations might seek a regional solution to regional asylum problems, even setting up regional processing centres. Wealthy countries may want to consider outsourcing the accommodation and processing of asylum seekers to impoverished client states or to other nations seeking a bilateral advantage. Offshore processing, like onshore processing, should include humane accommodation, transparent processing and prompt resettlement.

All countries - even those which are not net migration countries - have a responsibility to offer protection to those persons fleeing in direct flight from persecution. All countries are entitled to maintain the integrity and security of their borders. Being an island nation continent, Australia is more able than most to entertain the notion of hermetically sealed borders. Nations sharing land borders do not waste precious resources trying to exclude all unvisaed entrants.

Australia is less able to close off its borders because we want to retain possessions in the Indian Ocean which are much closer to Indonesia than to the Australian mainland. With possessions like Ashmore Reef, it is almost as if we share a land border with Indonesia.

Countries like Australia which are net migration countries should provide some humanitarian places in the migration program, as well as places for business and family reunion. Given the vast number of people facing persecution and human rights abuses in the world, net migration countries are entitled to set an annual quota of migrant places, including a quota on those requiring humanitarian assistance. The Houston panel has suggested a more generous humanitarian quota than Australia's average in recent years. This is most welcome.

Australia has a humanitarian interest in reducing the appeal of desperate asylum seekers making dangerous voyages in leaky boats from Indonesia. It is false to suggest that there is a queue or series of queues weaving like songlines across the globe - the right way to come being to join a queue and the wrong way to come being to jump the queue.

In some parts of the world there are queues. In other parts of the world (like Pakistan) there are not - there is only mayhem (as for the Hazaras fleeing from Afghanistan to Pakistan). Once asylum seekers have reached a place where an appropriate level of protection and processing is provided, they should wait there, and governments are entitled to design measures which encourage such waiting. The Houston panel suggested the need to enhance the prospects of people waiting, while at the same time ensuring that those who take to the boats not enjoy any advantage.

The ethical problem with the Pacific Solution Mark II is that it is impossible to calculate the usual waiting time for resettlement of asylum seekers in Indonesia. It is not as if everyone is placed in the one queue with the same treatment. Needier cases are often dealt with first.

If people are to be held on Nauru longer than is required for their processing and resettlement, either the Australian government officials will have to institute a "go slow" on processing, or the Nauruan government officials will have to breach numerous provisions of the Refugees Convention once persons are proved to be refugees awaiting resettlement. A proven refugee, as distinct from an asylum seeker awaiting processing, is properly entitled to be treated no less favourably than other visiting foreigners and in some instances to be treated as well as the citizens.

For example, there is no principled reason why a proven refugee should be denied the right to travel to other countries while awaiting resettlement. The Pacific Solution Mark II needs to work on the bluff that asylum seekers sent to Nauru will be denied resettlement and other refugee entitlements for as long as it would take to resettle them had they waited in Indonesia.

So we need to find an ethically more appropriate way to stop the boats. A regional solution to the regional problem will take many, many years, and Australia with its unduly sensitive, relatively small problem will not be the key player to determine that progress.

Here is my suggestion for a short-term Australian initiative that is both ethical and workable.

The way forward

Over the next 15 months, in the lead up to the federal election, Australian officials should redouble their efforts to seek a bilateral arrangement with Indonesia, with the co-operation of both UNHCR (which will be responsible for processing) and IOM (which will share responsibility with the Indonesian government for offering humane accommodation during processing and while awaiting resettlement). Under an enforceable memorandum of understanding (MOU) Indonesia would agree not to refoule any person whose asylum claim was awaiting determination nor any person proven to be a refugee.

Whereas UNHCR has 217,618 persons of concern on its books in Malaysia, it has only 4,239 in Indonesia. Other than the Sri Lankans, all asylum seekers who head to Australia by boat come through Indonesia. We need to set up a workable, transparent, honourable queue in Indonesia. Persons in the queue would receive appropriately deferential treatment from UNHCR deciding that the neediest cases would be dealt with preferentially.

What we need is for Indonesia to agree to an arrangement whereby Australia funds the accommodation and processing arrangements in Indonesia, with Australia setting an agreed quota of resettlement places from Indonesia. The quota needs the agreement of both governments - being sufficiently generous to assist clear the Indonesia caseload, and being sufficiently tight not to set up a "honeypot effect," thereby luring more asylum seekers to the Indonesian queue awaiting passage to Australia.

The human rights safeguards would need to match the requirements set by the Houston panel when reviewing the presently defective Malaysia proposal including "the operational aspects need to be specified in greater detail" and that "provisions for unaccompanied minors and for other highly vulnerable asylum seekers need to be more explicitly detailed and agreed."

The MOU would need to be accompanied by "a written agreement between (Indonesia) and UNHCR" and "a more effective monitoring mechanism" of human rights protection, including participation by Australian "senior officials and eminent persons from civil society."

Any person leaving Indonesia by boat for Australia could then be intercepted either before or after reaching the Australian mainland. They could be held briefly in detention while a prompt assessment was made whether they genuinely feared persecution in Indonesia. Almost none of them will. They could then be safely flown back to Indonesia and placed, quite literally, at the end of the queue. Should they attempt a boat journey again, they could be flown back having previously been informed that they would never be offered a resettlement place in Australia.

This would be a more ethical way of stopping the boats than indeterminate warehousing of people on Nauru and Manus Island. The increase of the humanitarian intake proposed by the Houston panel could then allow us to take more refugees from further up the transport chain.

***

In the lead up to the election, Tony Abbott and Scott Morrison are sure to continue insisting that the Gillard Government's Pacific Solution Mark II will not work. In all probability, this will undermine the efficacy of the Gillard Solution in stopping the boats. Just imagine if Kim Beazley had spent 2001 trumpeting that Nauru would never work and that people would end up in Australia anyway.

We can expect that there will be a cohort of people housed or detained on Nauru and Manus Island until the next election. The Houston panel has made it clear that towing back the boats is not a safe option at this time. The panel declined to recommend the re-institution of temporary protection visas (TPVs), presumably because they are convinced by the evidence that TPVs being issued to men simply results in women and children family members feeling compelled to get on the next boat, given that there is no other way to be a reunited family.

While hoping that the Pacific Solution Mark II - with the unworkable, unethical "no advantage" rule - will in fact stop the boats in the short term, despite the Abbott static, we need to build greater trust and co-operation with the Indonesians so that those asylum seekers, other than Sri Lankans, determined to get on a boat to Australia can be processed in Indonesia. If that works, we might then look to a one-off co-operative solution for the Sri Lankans much closer to home.

Father Frank Brennan SJ is professor of law at the Public Policy Institute, Australian Catholic University and adjunct professor at the College of Law and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, Australian National University

http://www.abc.net.au/religion/articles/2012/08/20/3571759.htm?WT.svl=featuredSitesScroller

-----------------------------------

Father Brennan despite being a "catholic" is a good guy... I have met him a couple of times and he has challenged George Pell on various occasions, big time. George Pell is too clever to have arguments with Father Brennnan, I believe...