Search

Recent comments

- warming....

20 min 58 sec ago - shutting dissent.....

42 sec ago - vassals....

2 hours 40 min ago - a repeatX3....

4 hours 48 min ago - who cares?...

5 hours 1 min ago - threats...

6 hours 1 min ago - suing...

10 hours 32 min ago - sacrifice....

13 hours 36 min ago - canned....

13 hours 52 min ago - AMOC runs amok...

1 day 1 hour ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

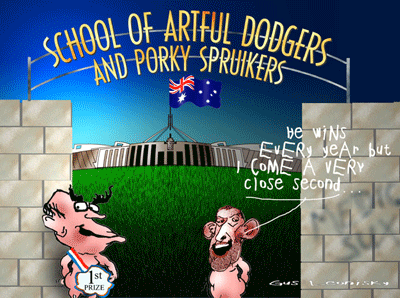

Artful dodger and his mate!

- By Gus Leonisky at 17 Apr 2005 - 6:58am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

liars inc... sponsored by howard and abbott...

Moreover, when the Whitlam government encountered economic problems, and advisers urged that slowing the reform momentum would be prudent, Whitlam was adamant that financial difficulties could be no alibi for delaying implementation of the program.

Abbott's approach could hardly have been more different. Having pledged during the 2013 campaign that he would lead a government of no surprises and no excuses, and having given repeated explicit assurances that there would be no cuts to health, education, pensions and the ABC, he proceeded in office to do precisely the opposite.

Unexpected decisions - a solitary woman in cabinet, no science ministry, and a retreat from the acclaimed Gonski system of school funding - came so thick and fast that commentator Annabel Crabb concluded within three months of Abbott becoming PM that he was leading "the Surprise Party". Then came the extraordinary budget, with its wide-ranging cuts that made a mockery of his election promises.

It was blatant, brazen and breathtaking - and still is. Abbott had declared during the campaign that he wanted "to be known as the Prime Minister who keeps commitments". Remarkably, even after the unfair 2014 budget, he has maintained with shameless effrontery that keeping promises is a priority for his government.

It's no wonder, then, that Abbott has become the first newly elected PM to miss out on a political honeymoon. Still, it's intriguing that he would be so cavalier with his credibility. Might another opposition leader, Abbott's idol John Howard, have provided an influential precedent?

Howard succeeded Paul Keating as prime minister at the 1996 election, having become opposition leader (for the second time) about a year earlier. During those months in opposition Howard delivered a series of vague "headland speeches" that were fluffy and non-committal, and repeatedly promised that he would not reduce expenditure on health, education, the ABC and other specific social programs. At the time Keating was profoundly frustrated that Howard's veracity was widely accepted and scrutiny was soft.

Later that year came Howard's "budget of betrayal", featuring savage cuts to health, education, the ABC and other social initiatives he had guaranteed he would retain. Howard airily dismissed his former undertakings as non-core promises. Angry protests culminated in a riot at Parliament House.

Abbott's familiarity with these events - he entered parliament in 1994 - has presumably influenced him to emulate Howard's modus operandi. (And might this now extend to the GST, which both Howard and Abbott promised in opposition not to touch?) It's a strategy not without risk: the Howard government almost lost the 1998 election, when Labor under Kim Beazley gained a sizeable swing and 51 per cent of the two-party-preferred vote.

Read more: http://www.smh.com.au/comment/abbotts-lost-credibility-no-surprises-no-excuses-20141107-11i82t.html#ixzz3IijEG2uv

We've been on this case since 2005... nine years ago...