Search

Recent comments

- bombing hospitals....

4 hours 5 min ago - commemoration....

4 hours 14 min ago - fair deal....

4 hours 47 min ago - trade off?....

7 hours 49 min ago - mad EU loonies.....

8 hours 28 min ago - one breast too many.....

9 hours 1 min ago - tanked bunnies.....

11 hours 25 min ago - Ugly State of America....

14 hours 19 min ago - stark choice.....

17 hours 23 min ago - a happy day.....

17 hours 56 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

russians voted against the commies in 1996...

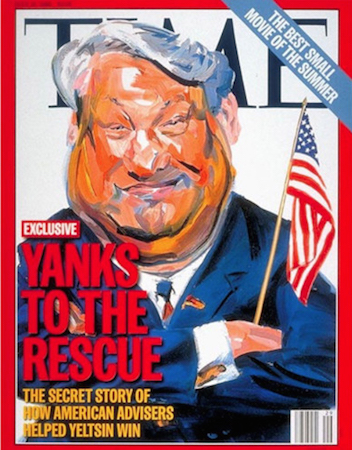

Patrick Armstrong explains why the Time magazine’s “Yanks to the Rescue” story was utterly wrong.

(This is the first of a two-part series on the 1996 Russian presidential election. They are based on notes I made at the time in the Canadian Embassy in Moscow. I was an accredited observer in both rounds in Moscow Oblast. A reporter accompanied me on the first round and a program appeared on CBC Newsworld, but I haven’t been able to find it on YouTube.)

When, four years ago, the losers concocted the story that the Russians had got Trump elected and beginning the unending series of stories, investigations and allegations, many people said that that was fair enough because Americans had got Yeltsin elected president of Russia in 1996. There was even a Time magazine story to that effect “Yanks to the Rescue“. You can see the argument made on this video.

I was there and I don’t believe it. I watched the polls carefully and a month before the first vote reported:

So the fundamental facts are these: Yeltsin is the only man who can stop the communists and Zyuganov is doing nothing effective to broaden his base from those who supported him in December… This election will be about the lesser of two evils and, at the moment, and with the dynamic of the situation, Yeltsin appears to enjoy that status.

Most Russians didn’t want the communists back and understood, that, like him or like him not – and he wasn’t popular – voting for Yeltsin was the only way to avoid them coming back.

I earlier published an anecdote of a conversation I had with a villager during the election who said that, while life in the village had been pretty dismal, he hoped it could be better for his children and that was why he was voting for Yeltsin. And he was correct: the route to the future did run through Yeltsin. Yeltsin gave way to Putin and the Putin team has achieved much. Russia in 2021 would look very different indeed had Zyuganov, still alive, won in 1996.

Therefore, 1996 was a tremendously important inflection point.

The first key to rationally analysing probabilities was to consider the election realities of Gennadiy Zyuganov, the head of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (KPRF). Any observer knew that the communists had a solid and dependable base that would certainly turn out. There was good data from the December 1995 Duma elections when all “communist” parties (not only Zyuganov’s KPRF) received about a third of the votes. It was a reasonable assumption that Zyuganov would retain most of this support six months later. “Brownshirts” took about another 20 percent with Zhirinovskiy’s party (LDPR) taking about half of that. It could also be assumed that he would stay in the race and keep most of his votes. But some of the “brownshirt” vote would go to Zyuganov who campaigned pretty hard for derzhava (Great Power State). Therefore, in January, before any polling was done, we could assume a theoretical maximum for Zyuganov of 35-40%. Zyuganov’s problem was how to attract the other 10-15%. He could get it by persuading people that he wasn’t really a hard communist; that would lose him some of his core but, because they had no other place to go, he could expect to keep most of them. The rules required a run-off between the top two if no one won over fifty percent on the first round. It was highly probable that Zyuganov would get to the second round; the question was who the other finisher would be.

And this is what the video referred to above doesn’t understand: Zyuganov had got the largest vote in December but he hadn’t got more than half; to win the presidency he had to get more than half. Zyuganov’s situation, not Yeltsin and Clinton, was the fixed background against which any analysis had to take place. None of this had anything to do with American whiz kids or money squandered on American-style pizazz: the fundamental reality of Russian politics in the 1990s was there was a strong core of communists – about a third of the population – who would certainly turn out and vote. And that was the situation that opinion polls showed in January: Zyuganov was well in front of Yavlinskiy, Zhirinovskiy, Fedorov and Lebed with President Yeltsin in the middle of the pack. Thus, from the perspective of January 1996, Zyuganov looked like the sure winner.

Some people have stuck at the January moment, failing to take the dynamics into account. But the December election had shown a second reality and that was that the majority did not want the communists back: the communists got a third but they didn’t get half. The dynamic of the interaction of these two realities was the key to understanding the election outcome. And over the next six months what I consider to be the central understanding gradually emerged: if you do anything but vote for Yeltsin, you are effectively voting for Zyuganov. Splitting the vote means Zyuganov wins; staying at home means Zyuganov wins. Only voting for Yeltsin will keep Zyuganov out.

There was one outlying pollster which, although differing from the others at the beginning, served to confirm this trend: Nugzar Betaneli and his Institute of the Sociology of Parliamentarianism. While the other pollsters asked for whom would you vote today, he claimed to be predicting the final result, although he never explained his methodology, and, as events showed, he wasn’t able to see any farther into the future than the others. In April he gave Yeltsin 16-20% and Zyuganov 38-47%. There was a rumour that his results accorded with the Kremlin’s internal polls and caused an apparent panic which was reflected in Korzhakov’s musings that the election should be postponed or cancelled.

But by May he had upped Yeltsin to 27% and dropped Zyuganov to 42%. In short, Betaneli agreed that Zyuganov was staying within his bounds but that Yeltsin had burst through his. This was the essence of the election dynamics. Betaneli agreed with other pollsters on the remaining candidates; his main disagreement was putting Zyuganov up to 15 points ahead of everyone else’s estimate. At this point numbers were less important than the dynamic. Again, there was no need for American legerdemain, just the reality that Zyuganov wasn’t expanding his appeal, a majority did not want the communists back and they were holding their noses and going for Yeltsin as the most viable alternative.

Two realities made Yeltsin the anticommunist centre: the first was the power of incumbency and the second the lack of a “third force”. He could have been pinched out had the “liberals” coalesced but that would have required Yavlinskiy, Fedorov, Lebed and Gorbachev to sink their differences and unite around one of them. Another scheme floated was a “government of national trust” uniting everyone and leading to a postponement of the elections. But nobody was willing to give over to another and neither of these ideas ever got off the ground. (This was the time of the colourful expression “taxi parties”: all the members could fit into a taxi and drive around in circles. But no taxi would ever merge with another.)

As time went on we could see people, understanding the dynamic, swallowing their misgivings and declaring for Yeltsin. Pamyat, the very first super-nationalist faction, declared for him; Yegor Gaydar, in opposition for more than a year, and Boris Fedorov, whom he fired, came over. Cossack leaders supported him because he’d done something for them. The Russian Orthodox Church quietly instructed its clergy to remind parishioners what the communists had done to it. Primorskiy Region’s Governor Nazdrachenko, who had strongly opposed the border settlement with China, supported him. Moscow Mayor Luzhkov, a very canny player, strongly supported him.

By late May the trend was very pronounced and Betaneli, for all his claims to be able to see farther, was no longer the outlier. The average of ROMIR, CESSI and VTsIOM gave Yeltsin 33.5% and Zyuganov 23.2%. Betaneli had the two even at 36% each. The dynamic was holding: Zyuganov stagnant and the other candidates leaking support to Yeltsin.

The last three polls were VTsIOM (11 June), ROMIR (10 June) and ISP (Betaneli) (7 June). All got the most important thing right which was the steady rise of Yeltsin’s rating over the campaign and the flatness of Zyuganov’s support through the same period. The first two got the order of the top five right; ISP had Yavlinskiy beating Lebed. VTsIOM had very accurate predictions for Yeltsin and Zhirinovskiy and the best fit for Lebed and did detect a rise in his score at the last moment (from seven to ten percent). ROMIR was best for Yavlinskiy and ISP best for Zyuganov. So, generally speaking, the pollsters were in the ball park; Betaneli/ISP, having reversed his starting position, had Yeltsin at 40% and Zyuganov at 31%.

I spent some effort calculating “correction factors” for the polling numbers because polling was pretty new to Russia and there were a lot of errors that observation over time had shown. Generally, “liberals” were over-estimated, Zhirinovskiy very under-estimated and communists somewhat under-estimated. But I kept to the lode star that, whatever the numbers produced by individual pollsters, the dynamic was the indicator: Zyuganov flat, Yeltsin gathering the others. And so my final prediction was that Yeltsin would win a second term although I thought he might come second to Zyuganov on the first round and I expected Zhirinovskiy to come third. For what it’s worth, a panel at the Carnegie Institute just before the vote estimated Zyuganov 31%, Yeltsin 28% and Zhirinovskiy 10-11%.

In the event, we were both wrong: in the first round Yeltsin edged Zyuganov 35.8% to 32.5, Lebed was a strong third at 14.7%, Yavlinskiy was 7.4 %, Zhirinovskiy 5.8% and the others were deep in the weeds (Brytsalov coming dead last. Anybody remember him? YouTube does). I observed the election counting at a military base near Moscow and there Lebed won comfortably with Yeltsin second.

One of the things that the Americans were supposed to have done was put some zip into Yeltsin’s campaign ads. I saw little evidence of that. Perhaps Yeltsin’s most effective ad was this one but there was nothing very impressive about the others. The best ads I saw were for Lebed. The one I most remember was at a work site where people were complaining that the country was going to the dogs and there wasn’t anyone who could lead the way out, a sprightly girl pipes up “есть такой человек, ты его знаешь!” (There is such a man, you know him) and Lebed’s face would appear. (And, amazingly, YouTube has preserved one of the series.) This played to his reputation as a man who could make hard decisions and was the very essence of мужественность (manliness, courage). Something he was to prove later in the year when he went to Chechnya, recognised the war was lost, and swiftly negotiated a ceasefire and withdrawal with Aslan Maskhadov. Zyuganov’s advertising was very Soviet – long screeds on cheap paper which probably didn’t shift a single vote.

The media coverage did heavily favour Yeltsin. Some of it was understandable: Yeltsin used the power of incumbency, was doing newsworthy things and his campaign style was far more active than Zyuganov’s; added to which, most reporters did not want a return to the days of GlavLit censorship. But the coverage was pretty heavy-handed: for example, in the last week, TV carried a program about the Cheka terror, an unflattering movie about Stalin and a hagiographic profile of Nikolay II. But Yeltsin ran a much better campaign than Zyuganov: he bribed the taxpayers with their own money (not unknown in our politics), apparently defused the Chechnya disaster, buried the health issue with his frenetic activity and directed his campaign to the issues people were concerned about; and he was cunning: in Novocherkassk he spoke of the strikers gunned down in 1962. So, while he shamelessly used the incumbent’s advantages, he did things that deserved coverage.

So, the dynamic operated: Zyuganov never got past his start state and Yeltsin gathered in the anti-communist vote. Not that surprising. American political operators had little effect.

Read more:

https://www.strategic-culture.org/news/2021/01/16/1996-election-the-americans-didnt-elect-yeltsin/

See also:

http://www.yourdemocracy.net.au/drupal/node/34276

Note: Gus has no idea of the bona fide of this article but it makes some sense to a point...

- By Gus Leonisky at 17 Jan 2021 - 3:28pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

a "russian" platform for exclusive analysis

The Strategic Culture Foundation is a Russian think tank that primarily publishes an online current affairs magazine of the same name. It is regarded as an arm of Russian state interests by the United States government.[1]

According to a 2020 United States Department of State report, the Strategic Culture Foundation is directed by the Foreign Intelligence Service, and is closely affiliated with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, U.S. government sources allege.[2]

It has been characterized as a conservative, pro-Russian propaganda website by U.S. media, but such reports allege the publishers of the site are unlikely to endorse any of the specific political positions espoused in the publication.[3][4]

One of the leading columnists is the American conservative journalist and former CIA officer Philip Giraldi, who has contributed pieces on numerous political issues, including the history of fascism and criticism of Zionism.[5]

Read more:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strategic_Culture_Foundation

The Strategic Culture Foundation provides a platform for exclusive analysis, research and policy comment on Eurasian and global affairs. We cover political, economic, social and security issues worldwide. Since 2005, our journal has published thousands of analytical briefs and commentaries with the unique perspective of independent contributors. SCF works to broaden and diversify expert discussion by focusing on hidden aspects of international politics and unconventional thinking. Benefitting from the expanding power of the Internet, we work to spread reliable information, critical thought and progressive ideas.https://www.strategic-culture.org/about/

Propaganda is in the eye of the ground keeper...

Note: the writer of the piece above says: "American political operators had little effect" DOES NOT MEAN THAT THERE WERE NO AMERICAN POLITICAL OPERATORS. Presently, It appears to Gus that Navalny is being used by the West to unsettle Putin.

Navalny has been "arrested" in Moscow or whatever reasons (possibly for tax irregularities) as he had been warned by the authorities should he come back to Russia from Germany where had treatment for his "poisoning".