Search

Recent comments

- "good" nazis....

3 hours 20 min ago - british evil....

3 hours 27 min ago - nazi merz.....

5 hours 37 min ago - jewish brat.....

5 hours 53 min ago - mercenaries....

6 hours 7 min ago - sad case.....

6 hours 18 min ago - softening....

17 hours 51 min ago - welcome uncertainty...

18 hours 3 min ago - a good pope....

1 day 5 hours ago - natural law?....

1 day 8 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

putting science to work for peace...

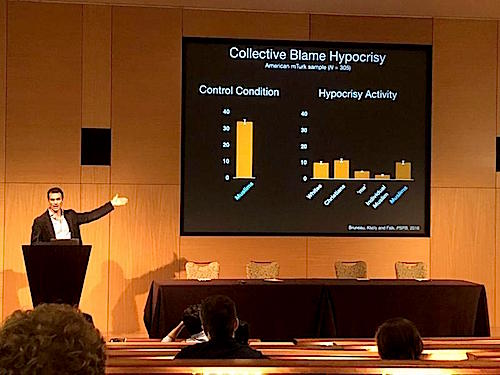

Having seen groups in conflict all over the globe, Bruneau began to reflect on how the antipathy people have about opposing groups was surprisingly consistent.

With these ideas in the back of his mind, at 29, Bruneau entered a Ph.D. program at the University of Michigan in cellular and molecular neuroscience. While there, his research team discovered that synapses – the connections between nerves and their targets – are incredibly dynamic, driving home to him that at the sub-cellular level, our brains are made to change.

While he loved looking at how brain cells change, Bruneau was drawn more to questions about how mindschange, and specifically how to turn conflict into peace. Realizing he would need to learn the tools of human neuroimaging, he approached Rebecca Saxe, Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience at MIT, and over the course of an intense three-hour conversation, talked her into taking him on as a postdoctoral fellow. Focusing on empathy, he used fMRI to study the brains of people on opposite sides of conflicts, such as Israelis and Palestinians or Republicans and Democrats. He began to identify brain regions associated with conflict and how different experimental interventions altered participants’ brain activity.

In 2015, Bruneau moved to the Annenberg School at Penn to become a visiting scholar in Professor Emily Falk’s Communication Neuroscience Lab. He found the discipline of Communication a welcoming one. After a year, he made the move to Philadelphia permanent, becoming a Research Associate and Lecturer at Annenberg and taking on several postdoctoral fellows.

At Annenberg, Bruneau established the Peace and Conflict Neuroscience Lab, whose tagline neatly summarizes Bruneau’s professional mission: “putting science to work for peace.”

Read more:

https://asc.upenn.edu/news-events/news/memoriam-emile-bruneau-peace-and-conflict-neuroscientist

- By Gus Leonisky at 4 Nov 2020 - 5:34am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

bottling the goodness of us...

...

And he didn’t just talk about that system; he spent more than a decade trying to build it. He traveled to conflict zones around the world, mapping the neurological correlates of human discord — the hatred too many of us feel toward specific groups, how we dehumanize our enemies — and searching for ways to dampen those signals.

He had Palestinians and Israelis watch videos of one another talking about their hardships. He designed elaborate experiments involving actors to measure racial prejudice among Hungarian schoolteachers. He scanned the brains of Democrats and Republicans for clues about how conflict mutes empathy.

Emile learned a great deal from this work: Groups often overestimate the extent to which other groups hate them. Even people who commit horrible violence can be deeply empathetic. And most minds really can be changed, intentionally, for the better.

He never quite figured out how to bottle up the best in us and use it to treat or cure the worst in us. But he also never stop believing that such deliverance was possible.

Read more:

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/02/opinion/emile-bruneau-dead.html

Bruneau attended Stanford University where he majored in human biology - a track combining biology with psychology, sociology and anthropology — which was well-suited to his interdisciplinary way of thinking. He competed on the Stanford rugby team, where he was known for both the ferocity of his tackle and the integrity of his sportsmanship.

As one can "suffer" from sporting "incidents", one should look at this:

There are an estimated 1.7 to 3.8 million traumatic brain injuries each year in the United States, according to the CDC, of which 10 percent arise due to sports and recreational activities. Amongst American children and adolescents, sports and recreational activities contribute to over 21 percent of all traumatic brain injuries. Sustaining an injury while playing sports can range from a mild physical trauma such as a scalp contusion or laceration to severe TBI with concurrent bleeding in the brain or coma. It is important to recognize when a head trauma is severe or has resulted in a TBI because it is crucial to seek immediate medical attention. While most brain injuries are self-limiting with symptoms resolving in a week, a growing amount of research has now established that the sequelae from recurrent minor impacts is significant in the long term.

Read more:

https://www.aans.org/en/Patients/Neurosurgical-Conditions-and-Treatments/Sports-related-Head-Injury

a bad natural heritage...

Around 600,000 years ago, humanity split in two. One group stayed in Africa, evolving into us. The other struck out overland, into Asia and then Europe, becoming Homo neanderthalensis – the Neanderthals. They weren’t our ancestors (with the exception of a little interbreeding), but a sister species, evolving in parallel.

Neanderthals fascinate us because of what they tell us about ourselves – who we were, and who we might have become. It’s tempting to see them in idyllic terms, living peacefully with nature and each other. If so, maybe humanity’s ills – especially our territoriality, violence, wars – aren’t innate, but modern inventions.

Biology and palaeontology, however, paint a darker picture. Far from peaceful, Neanderthals were likely skilled fighters and dangerous warriors, rivalled only by modern humans.

Predatory land mammals are territorial, especially pack-hunters. Like lions, wolves and our own species Homo sapiens, Neanderthals were cooperative big-game hunters. Other predators, sitting atop the food chain, have few predators of their own, so overpopulation drives conflict over hunting grounds. Neanderthals faced the same problem – if other species didn’t control their numbers, conflict would have.

This territoriality has deep roots in humans. Territorial conflicts are also intense in our closest relatives, chimpanzees. Male chimps routinely gang up to attack and kill males from rival bands, a behaviour strikingly like human warfare. This implies that cooperative aggression evolved in a common ancestor of chimps and ourselves, at least seven million years ago. If so, Neanderthals will have inherited these same tendencies towards cooperative aggression.

Read more:

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20201102-did-neanderthals-go-to-war-with-our-ancestors

See also: http://www.yourdemocracy.net.au/drupal/node/8011

(more than 36,000 reads)