Search

Recent comments

- whitewashing....

1 hour 36 min ago - defenestred....

1 hour 47 min ago - flash floods....

1 hour 59 min ago - still at it.....

2 hours 9 min ago - in the SMH....

2 hours 14 min ago - no-good guest....

2 hours 20 min ago - WAR?......

3 hours 11 min ago - why wait?....

3 hours 24 min ago - still looking....

6 hours 21 min ago - sending troops....

6 hours 31 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

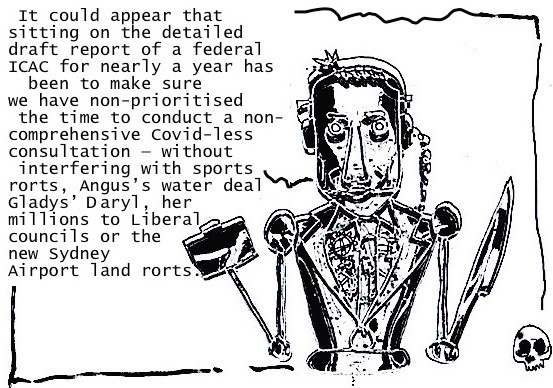

a lame excuse for sitting on their butts...

The Morrison government insists coronavirus is behind delays in establishing an anti-corruption commission, despite receiving a draft bill in December 2019.

Senior officials from Attorney-General Christian Porter’s department presented him with an exposure draft of the legislation about 10 months ago.

Deputy secretary Sarah Chidgey detailed the timeline at a Senate estimates hearing in Canberra on Wednesday.

“Part of the consideration with COVID is making sure that it’s an appropriate time to conduct a comprehensive consultation process,” she told the committee.

“That has been part of the reason for delaying release of that exposure draft.”

Labor senator Murray Watt was flabbergasted by the delay.

“Wow. So he’s been sitting on it since last year?” he said.

The Coalition committed to establishing a federal anti-corruption commission almost two years ago.

A corruption scandal engulfing former NSW Liberal MP Daryl Maguireand a controversial $30 million federal land purchase have reignited calls for a national body.

Government minister Zed Seselja said Mr Porter would release the exposure draft soon.

“We have been dealing with the COVID crisis and the Attorney-General in a range of capacities of course has been dealing with that response,” he said.

He said getting the detail right was important.

Senator Watt questioned if the Coalition had decided fighting corruption could wait.

“The government’s argument as to why it has not been able to deliver a Commonwealth integrity commission that it promised nearly two years ago is that there’s just too much going on,” he said.

Department secretary Chris Moraitis said some resources had been diverted to industrial relations reform, which the government considered more pressing.

He said the department had progressed work relating to the commission as far as it could and was now waiting for the exposure draft’s release.

“We respond to the minister’s priorities and we have other areas of priority we’ve been dealing with as well,” Mr Moraitis said.

-AAP

Read more:

https://thenewdaily.com.au/news/national/2020/10/21/federal-icac-coalition-legislation/

- By Gus Leonisky at 21 Oct 2020 - 6:40pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

their hands were tied behind their backs...

A United States Marine Corps (USMC) helicopter crew chief says Australian special forces shot and killed a bound Afghan prisoner after being told he would not fit on the US aircraft coming to pick them up.

Key points:

Josh* flew 159 combat missions for the USMC's Light Attack Helicopter Squadron 469 (HMLA-469).

He has allowed the ABC to publish pictures of him but has asked that we don't use his real name because he fears retribution.

He has told ABC Investigations he was a door gunner providing aerial covering fire for the Australian soldiers of the 2nd Commando Regiment during a night raid in mid-2012.

The operation took place north of the HMLA-469 base at Camp Bastion in Afghanistan's Helmand Province.

It was part of a wider joint Australian special forces-US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) campaign targeting illicit drug operations that were financing the Taliban insurgency.

"We had done the drug raid, the Aussies actually did a pretty impressive job, wrangling all the prisoners up," Josh said.

"We just watched them tackle and hogtie these guys and we knew their hands were tied behind their backs."

Read more:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-10-21/soldiers-killed-man-who-could-not-fit-on-aircraft-says-us-marine/12782756

slack on the paperwork...

The Berejiklian government handed out more than $250 million in council grants, almost all in Coalition-held seats, in the months before last year's election without any signed paperwork.

The government has confirmed no signed approvals exist for 249 grants rubberstamped between June 27, 2018, and March 2019 from the Stronger Communities Fund, established after council mergers.

Premier Gladys Berejiklian directly approved more than $100 million in the grants, but the only records of the approvals are in the form of emails from policy advisers.

After a tumultuous week, Ms Berejiklian is bracing for another bruising parliamentary period, with all focus to be on her secret five-year romance with disgraced former MP Daryl Maguire and the return to work of NSW Nationals leader John Barilaro.

Read more:

https://www.smh.com.au/politics/nsw/coalition-faces-bruising-week-amid-premier-s-romance-and-grants-scandal-20201018-p5667v.html

See toon at top.

what did you expect?

'The big guys get whatever they want': Western Sydney airport, wealthy landowners and the Coalition

Land deals near Sydney’s second airport have embroiled the NSW and federal governments in separate scandals, feeding perceptions of favouritism

In October 2016, well before the Western Sydney airport land scandal exploded into public view, the conservationist Ross Coster was sitting in a committee room, tucked away in the halls of parliament house.

Coster, the head of the Blue Mountains Conservation Society, had travelled south with representatives of two local residents’ groups to share their concerns about the proposed airport development with Paul Fletcher, then responsible for urban infrastructure, and Josh Frydenberg, the then environment minister.

To his surprise, he arrived to discover two of the wealthiest landholders in the region, Mark Perich and Louise Waterhouse, were also in the room, among others.

Both spoke glowingly of the project.

The tenor of the meeting, Coster says, shifted completely, turning from one of opposition and concern to support and praise.

“I thought we were ambushed. I thought the three of us were going to meet the minister,” Coster says. “I had no idea there was going to be other people there and that all of the other people would be pro-airport.

“It put us in a difficult position. He let everyone talk for two minutes around the table and at the end of it, the consensus you got was the airport was marvellous.”

Privileged access for those ‘with a bucket of money’It’s no great surprise that Perich and Waterhouse were consulted over a development happening right on their doorstep.

Read more:

https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/oct/24/the-big-guys-get-whatever-they-want-western-sydney-airport-wealthy-landowners-and-the-coalition

Hey, Ross, what did you expect? These guys are CONservative and pro-development, including the "environment" minister, whoever he/she is in that party of concrete merchants and privatisation.

Have a look at age care, where most of the Covid-death happened...

"You know, it was predicted … when these proposals were made in 1997, when the changes were made. … and documented multiple times since," she said.

Ms Saltarelli has long argued that introducing partially privatised for-profit aged care was a mistake.

"The pressures to be profitable, combined with the lack of accountability, ensured that this would happen," she said.

Others said the memo was an example of how one possibility raised by bureaucrats could transform from an idea into policy.

"The thing is that … the aged care sector has really run away with the rationalisation of care and has used it to its own advantage," said Paul Versteege, a long-time observer of aged care funding with the Combined Pensioners and Superannuants Association.

"Both the private sector and private providers and also too many of the charitable ones have used it to set up empires.

"They have made huge profits, and that has gone on at the expense of the people that this system is meant to serve."

Read more:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-10-24/10-page-aged-care-memo-waiting-lists-and-quotas/12807592

Read from top.

giving crooked pollies time to clean up...

The Government's long-anticipated integrity commission will not be in place for at least six months, Attorney-General Christian Porter confirmed today.

Key points:

Marking the release of the proposed bill for the new body "with greater powers than a royal commission", Mr Porter confirmed at least half a year would be needed for consultation.

"That will obviously be amongst the public sector, civil society, stakeholders, all of the states and territories," he said.

"It's a complicated piece of legislation."

Three hundred and ninety pages of draft laws were published on Monday, setting out a model for a Commonwealth Integrity Commission (CIC).

It would be split into two divisions, one investigating enforcement agencies like the federal police and immigration officials, the other looking at the public sector and MPs.

The former will have the discretion to hold public hearings, but that power won't extend to the division investigating politicians.

Mr Porter conceded some may lobby for public hearings across both divisions, "but the alternative argument is that when you've got a body whose powers are so great … the government takes the view that ultimately a court should be making a public determination of guilt or innocence."

"That is a view that some people will agree with and some people may not agree with and one of the reasons you've got to have an extensive consultation process."

Under the Government's model, the public sector division would prepare briefs to pass to the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions, which would then pursue matters in court.

Read more:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-11-02/commonwealth-integrity-commission-bill-cic/12812830

Read from top.

conflict of interest...

By IAN CUNLIFFE | On 2 November 2020It is not a pretty picture. Bernard Keane writing in Crikey said recently: “Everywhere you look in the Morrison government, you see sleaze and self-interest, if not outright corruption. Merely itemising the current scandals on foot is an arduous task.”

Keane provided a list but it was far from comprehensive. He didn’t mention Mathias Corman’s Hello Worldtravel for his family. Hello World has done very well out of the Federal Government. It is another case where police investigated the leak of the information rather than the possible criminal breach itself. Nor did Keane mention the buses used by Christian Porter as advertising vehicles before the last federal election, which were only paid for after the transaction went public. No Godwin Grech was needed for that one. The CEO of the bus company was elevated to the AAT. Nor Stuart Robert’s enormous internet account. Nor Susan Ley’s travel expenses. These are all federal ministers, as is the trouble-prone Angus Taylor. Is Alan Tudge’s proclaimed criminality in disregarding orders by the AAT to release a man from imprisonment corrupt, or just contempt for the law – apparently sanctioned by Australia’s First Law Officer, the same Christian Porter, whose duty it is to see the law upheld.

It’s not so long ago that the Australian Wheat Board was up to its neck in corruption, and the Reserve Bank, of all people, was not immune, with Securency.

But it is not just about reciting a litany of scams.

Underlying value/culture problems are creating the tsunami of corruption. Milton Friedman created the underlying values system of the last 35 years – Gordon Gekko said that greed is good, but he was just parroting Friedman. Friedman proclaimed that there is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game. To be fair to Friedman, we only heard and acted on the first part of the proclamation, but not the caveat: “so long as it stays within the rules of the game”.

In Australia, Friedman’s pernicious ethos was inflicted on the public sector as well as business. It led to corporatisation of the public sector and managerialism. Everything had to be contestable and everything a market. One of the ironies is that, increasingly, large amounts of public money are being spent without contestability – without a tender.

Since the 19810’s it has become an article of faith that talented people will not take on public service unless they are paid top dollar – no matter that the evidence of decades was thrown overboard. Think of HC “Nugget” Coombs, JG Crawford, Douglas Copland, Sir William Hudson – a very different man from his trouble-prone grandson. Angus Taylor would have made a fortune out of the Snowy Scheme.

It all came to be about the money. “Just show me the money!” Senior executives in bodies such as ASIC and Australia Post, and their Boards and internal auditors and those with internal governance roles in such entities have lost the plot. It’s too long since they were in the public bar of a pub to sense what will fail the pub test.

When people have been caught out rorting, very often they have been able to get out of that embarrassing jam simply by paying the money back. It is not an option if you rob a bank. So, as long as you don’t wield a gun, have a go. If you get caught, you’ll probably just have to pay it back.

As a lawyer who often interacts with the public sector, every week I encounter public sector bodies which simply disregard the law. They deliberately act illegally or don’t even consider the law as being of sufficient importance to be bothered asking about what it requires. In the past week, both Scott Morrison and David Littleproud have shot their mouths off: Morrison basically suspended the CEO of Australia Post without pausing to wonder whether that is one of the powers of the Prime Minister; Littleproud threatened to revoke deposit guarantees for ANZ Bank as revenge for its stricter climate policy. Laura Tingle wrote: “Littleproud and the band of Nationals MPs and senators who joined the ANZ-bashing conga line seemed to have little regard for things like a bank board’s obligation to make risk management decisions in the best interest of their shareholders, or indeed to be transparent about their actions. But maybe that is not all that surprising. It is hard to think of a recent government that has done more to reduce transparency or frustrate inquiries into activities carried out in its name.”

Sports Rorts is another case in point: $100 million was handed out for political gain and in total disregard of the governing Act. ASIC’s stated (when pressed for an explanation) policy not to oversee the activities of not-for-profit companies is another example. ASIC has the duty. But without publicising it, ASIC just don’t do that part of its duties.

The new disregard for ethics and integrity is seen in the explanations our leaders try to float when they are caught out. Deputy Prime Minister Michael McCormack suggested that paying $30 million to Liberal party donors for a bit of land worth $3 million would look like good value one day! Presumably he was reduced to that explanation after the Government’s two favoured explanations – that corruption isn’t a problem at federal level; and that the Federal Government can’t walk (respond to Covid) and chew gum (publish its anti-corruption proposal) at the same time – had failed that same pub test.

On a wider front, suddenly the Coalition has flipped from its forever opposition to picking winners. The Government has announced that its policies to get the economy moving again are based on picking winners – we are going to support six priority industry sectors: advanced manufacturing, cyber security, food and agribusiness, medical technologies and pharmaceuticals, mining equipment, technology and services, and oil, gas and energy resources.

This is a Government which can’t give $100m in sports grants to the properly selected clubs when there is a better (but illegal) option of picking up some marginal seats. What hope have we got with billions and billions of dollars which we are in the process of spending where there are no rules?

The whole exercise has been guided by hand-picked people from the industries which are set to benefit massively from this new game. Did I hear “conflict of interest”?

Read more:

https://johnmenadue.com/ian-cunliffe-is-it-time-for-federal-integrity-bo...

Read from top.

worse than bad...

Porter's plan will help cover up corruption, not expose it

When I first read Attorney-General Christian Porter’s proposal for a Commonwealth Integrity Commission, I thought that he was just putting forward a bad model. But then I realised it was worse. Much worse.

The proposed model is badly flawed. The structure, for instance, is all wrong. Why are the activities of the commission divided into a “law enforcement” part and a “public sector” part? Why, for example, should law enforcement officers, of whom the Attorney-General is the notional head, be held to a higher and different standard than the Attorney-General himself? Why do politicians get special protection?

The commission will find it nearly impossible to investigate anything. Very few persons can refer a matter to the watchdog. In practical effect, only politicians may do so. That excludes any referral from the public, or from contractors or bureaucrats – and this would be so, even where that person is specifically aware of actual corruption.

Not even the Auditor-General can make a referral — he or she would need to refer it to another politician and then keep their fingers crossed. Bear in mind that the ICAC’s inquiry into the Obeid family began following an anonymous tip-off. Under Mr Porter’s model, his commission would not be permitted to act on that call.

Read more:

https://www.smh.com.au/national/porter-s-plan-will-help-cover-up-corruption-not-expose-it-20201103-p56b0e.html

Read from top.

the drop that overflows the bucket...

From Cathy Wilcox — the best cartoonist of our rorting times...

Read from top.

like an old beer-stained pub carpet...

Another brilliant toon by Cathy Wilcox... Read from top.

designed like a failure waiting to become a flop...

By SPENCER ZIFCAK | On 11 December 2020Recently, a team from Transparency International and Griffith University released an important report. The report, Australia’s National Integrity System: A Blueprint for Action, proposed that an entirely new and comprehensive governmental integrity system be developed in Australia. Plainly the report picked up on the fact that public concern with the abuse of public power for private or political gain has been escalating significantly. Instances of governmental corruption have attained a level of crisis federally and in states.

The concern with corruption and misconduct in public office has crystallised in the current debate about the appropriate powers and procedures of a prospective Federal Integrity Commission. Helpfully, the Transparency International Report has identified a number of criteria which such a Commission should fulfil if it is to be considered effective. The key criteria are:

1. There should be common minimum standards of professional and ethical conduct for all federal public officials irrespective of their role or status.

2. There should be a comprehensive scope for the Federal Integrity Commission to investigate any conduct – criminal and non-criminal – which undermines confidence in the integrity of public decision-making.

3. The Commission should have full capacity to receive and act upon corruption information from any person.

4. The Commission should have full powers to hold compulsory hearings (public and private), conduct investigations and make public reports wherever these are in the public interest.

These criteria seem unarguable. Christian Porter’s draft Commonwealth Integrity Bill, however, fails on almost everyone. It’s worth looking at the Bill against these criteria in order to evaluate its efficacy and deficits. This evaluation can be assisted by comparing the Porter draft’s provisions with those contained in the Private Member’s Bill on the same subject advanced by the independent Member for Indi, Helen Haines. She was advised in its drafting by a committee of highly regarded former judges and academic experts.

The most striking feature of the Porter Bill is the bifurcation it creates between law enforcement agencies on the one hand and public sector agencies on the other. In contradistinction to the first criterion noted above, these two segments of the public sector are treated quite differently. The law enforcement division, which consists of eleven law enforcement agencies, is held to quite rigorous anti-corruption standards. The public agency division’s anti-corruption standards are wayward and weak.

Take for example the Porter Bill’s definition of ‘corrupt conduct’ and ‘a corruption issue.’ A law enforcement corruption issue is an issue as to whether a person has engaged in corrupt conduct; is engaging in corrupt conduct; or may in the future engage in corrupt conduct.

A public agency corruption issue is an issue as to whether a person has engaged in corrupt conduct; or is engaging in corrupt conduct. In this division, therefore, there is no reference in the definition of engagement in corrupt conduct in the future. Impending corrupt activity escapes the Commission’s concern.

Next, the Porter draft defines what it is to engage in corrupt conduct. An official of a law enforcement agency engages in corrupt conduct if that official abuses their public office; perverts the course of justice; or engages in conduct ‘for the purpose of corruption of any other kind.’

In contrast a staff member of a public sector agency – for example, a Minister, parliamentarian, political staffer or public official – engages in corrupt conduct if they abuse their office or pervert the course of justice and if they engage in conduct that constitutes a criminal offence.

The reference to engagement in a criminal offence sets an extraordinarily high bar before the Federal Integrity Commissioner can initiate a public sector corruption investigation. A normal pattern would be that the Commissioner would initiate an investigation and, as part of that investigation, would determine whether or not any corruption-related criminal activity has occurred. To set down a requirement that before commencing a corruption inquiry the Commissioner should reasonably suspect that criminality has occurred in-effect pre-judges an investigation’s outcome. It restricts the investigation of corruption to criminal conduct alone.

It excludes from inquiry and investigation any and all actions short of criminality, for example, misconduct in public office, dishonestly benefiting from the application of public funds for private advantage, and impropriety in government procurement. Each of these actions is commonly and properly understood as conduct constituting corruption – but not in this draft law.

To narrow the definition of engagement in corrupt conduct in this way makes a mockery of what an effective federal integrity commission is designed to be. According to the second criterion set down by the Transparency International report, a Commission should be able to investigate any conduct – criminal and non-criminal – which undermines confidence in the integrity of public decision-making. The Porter Bill comes nowhere near to conformity with that criterion.

The Helen Haines Bill overcomes all these difficulties by providing a clear and comprehensive definition of corrupt conduct and applying it uniformly and equally to every facet and activity of public administration. The complex and unnecessary distinction between law enforcement agencies and public sector agencies does not appear.

“Corrupt conduct is any conduct of any person that adversely affects,…either directly or indirectly, the honest or impartial exercise of official functions by any of the following: the Parliament, a Commonwealth agency, any officials, (and) any conduct of a person that involves…a public official in placing private interests over the public good”.

The third criterion set down in the Transparency International report requires that a Federal Integrity Commission should have full capacity to receive and act upon corruption information from any person.

The Porter Bill places strict restrictions upon the Commission’s authority to receive individuals’ allegations of corruption. A member of the public, even if possessing strong evidence of public sector corruption, cannot refer a public agency corruption issue to the Commissioner.

Referrals may be made only by specified agencies including. for example, the Commonwealth Ombudsman and the Australian Federal Police.

This referral provision would exclude every genuine whistleblower from direct access to the Commission. The Commissioner could accept a whistleblower’s complaint only if it is filtered through and endorsed by a Commonwealth department or agency. This represents a very high hurdle.

By contrast, Helen Haines’ draft provides simply that a person may refer an allegation, or information, that raises a corruption issue directly to the Commissioner.

In conformity with the third criterion, when acting upon alleged corruption, the Federal Integrity Commission should have the power to initiate corruption investigations on its own initiative. The Porter Bill, however, does not provide the Commission with unfettered discretion as to the commencement of such an investigation.

The Commissioner may initiate an own motion investigation only where in the course of an existing investigation he or she becomes aware of an allegation of corruption and the Commissioner reasonably suspects that the offence to which the allegation relates has been or is being committed. Here again, the Commissioner appears restricted to investigating suspected criminal conduct only.

The Haines Bill dispenses with this fetter. It provides that the if Federal Integrity Commissioner becomes aware of an allegation that raises a corruption issue, the Commissioner may on his or her own initiative deal with the corruption issue.

The fourth Transparency International criterion states that the Commission should have full powers hold compulsory hearings (public and private), conduct investigations and make public reports wherever these are in the public interest. The Attorney-General’s draft Bill, however, rules out public hearings in relation to investigations of Ministers, parliamentarians, political staffers, public sector agencies and their officials.

It is beyond doubt that public hearings with respect to matters of corruption are an essential weapon in an integrity commission’s arsenal. They form a crucial component of a rigorous process of investigation. Public examinations of persons allegedly involved in corruption place intense pressure on those accused to provide honest answers to questions. Untruthful answers to questions carry the public stigma and probable penalty of perjury.

Public hearings serve to inform the wider public of the nature of, and damage caused by, corrupt activity. The stigma, embarrassment and, possibly, humiliation associated with the requirement that a person accused of corrupt activity should account for their actions to a community of their peers serves as a powerful deterrent to others who may contemplate similar conduct.

Helen Haines’ Bill deals with the subject of hearings in a careful and balanced way. It provides that the Commissioner may hold a hearing for the purpose of investigating a corruption issue. The Commissioner may decide to hold the whole or part of a hearing in public or private if he or she considers it is in the public interest to do so.

In making that determination, the Commissioner is required to consider whether any unfair prejudice to a person’s reputation or unfair exposure of a person’s private life may occur by virtue of the hearing being conducted in public.

There are other significant deficits in Mr Porter’s Bill that I do not have the space to canvass here. The cloak of secrecy that Bill throws over the entirety of the investigative process is one of them.

In conclusion, when commenting on the differential treatment in the Bill of law enforcement officers and public agency officials, the President of the Australian Federal Police Association described the far more protective treatment of malfeasance by Ministers, parliamentarians and public officials as unfair.

‘You can’t just say my mates get this and everyone else gets that. It’s almost like creating a protection racket for their parliamentary mates. It’s very much an us and them situation.’

He is right. It is a protection racket. Mr Porter’s Bill is a politically self-interested flop. He can’t be serious.

Read more:

https://johnmenadue.com/christian-porters-federal-integrity-commission-is-a-complete-flop/

Read from top.

acceptable pork barrelling?...

Why can’t we agree on the powers needed for a Commonwealth Integrity Commission?

By Quentin Dempster

Ministerial discretion under the Westminster system as it is applied in Australia is a useful but corruptible power.

Regardless of informal or formal departmental or a contracted expert consultant’s advice, a minister can order expenditure up to a set limit or approve or refuse applications under his or her ministerial control designated by relevant acts of parliament.

In New South Wales at the moment we are waiting on Justice Elizabeth Fullerton’s (judge alone) verdict on the conduct of former minister Ian Macdonald and the exercise of his discretion in issuing a lucrative coal mining exploration licence (EL) to former Upper House member Eddie Obeid over his Bylong Valley property. Her honour must decide if the former minister has criminally misused his discretion by facilitating the EL allegedly in secret with Eddie Obeid and his son Moses Obeid.

This case seems likely to set a precedent. There was no evidence that Mr Macdonald had been bribed or would receive any personal benefit by approving the EL. So, given the absence of such evidence, can ministerial discretion be fettered?

In Queensland in the 1980s then Minister for Roads and Racing, Russ Hinze, famously applied his discretion to approve the construction of an off ramp of the Bruce Highway into his hotel’s drive-in bottle shop and reallocated to the hotel its own TAB licence. It was denounced in parliament under privilege as Queensland’s only ministerially approved “six pack, six pick” highway stop.

Apart from generating widespread hoots of laughter, derision and outrage it was all quite legal. The minister’s discretion was unfettered.

Those Queensland journalists and citizens who asked questions about then Premier Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s personal business interests conflicting with his ministerial duties were denounced as politically motivated, anti-private enterprise and anti-Queensland.

It took the ground-breaking Fitzgerald inquiry in the late 1980s to nail the consistent failure of Queensland’s Justice Department over decades to alert executive government to corruption risk. As a result structural reform including an anti-corruption body that could investigate ministerial indiscretions and misconduct was established in the Queensland jurisdiction.

On many occasions Queenslanders have seen their ministers being called into the witness box to be held to account over questionable or corrupt conduct. Prosecutions often resulted from these investigations.

In contemporary times auditors and media outlets have exposed what is now headlined as the sports rorts, regional renewal and the community grants scandals where ministerial discretion was used for electoral advantage, more commonly known as pork barrelling.

Merit assessment rankings of hundreds of applications for taxpayer grants via published criteria were often overridden by ministerial discretion.

The latest scandal exposed by the Australian National Audit Office concerns the commitment of funds for political advantage in a $600 million commuter car park construction scheme announced just before the 2019 federal election. Said to be necessary to relieve congestion, the ANAO found that 64 per cent of projects were in Melbourne in spite of the country’s greatest congestion being in Sydney.

It found that 77 per cent of projects were in Coalition-held seats with 10 per cent in seats held by Labor at the time but picked up by the Coalition at the election.

Some sites acquired for car parks were not close to railway stations when the objective of the scheme was to enhance public transport use to reduce citywide congestion. ANAO found that no project had been proposed by the urban infrastructure department and “was not demonstrably merit based” and followed canvassing of local Coalition MPs or candidates for certain seats. There was only “limited engagement” with state government and some councils.

It is pertinent to note with these contemporary examples of pork barreling that at no time has the Attorney General’s Department and its director general been reported to have alerted executive government to the potential for abuse of ministerial discretion.

Pork barreling has been declared a form of corruption by integrity experts but also dismissed by those state and federal ministers so accused as the result of effective representation by MPs on behalf of their electorates and constituents and more broadly defended as part of the spoils of office. Wink wink. Nudge nudge.

Public trust in government has been measured in opinion surveys as negligible.

As public consciousness about corruption has increased over the years there have been efforts to minimise risk and damaging perceptions by introducing pecuniary interest registers for ministers and MPs and ministerial codes of conduct. Donations to political parties, also known as “slush funding” by vested interests and industry lobbies, are now conditionally required to be published.

Also in play at the moment is a NSW ICAC recommendation that ministers should publicly and transparently declare their access meetings with industry and vested interest lobbyists as they are scheduled.

Currently New South Wales Premier Gladys Berejiklian is awaiting formal findings of the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption in the examination of her adherence to her own Cabinet ministerial code of conduct.

The Premier denied under oath that her relationship with former MP Daryl Maguire was “intimate”. Such an admission would have obliged her to make a declaration under the ministerial code of conduct in the event that the relationship could be seen to have advantaged Mr Maguire’s personal business activities.

The ICAC had begun an investigation into Mr Maguire following complaints received about his alleged conflicts of interest as an MP. These inquiries led to the discovery of Mr Macguire’s relationship with Ms Berejiklian. The NSW ministerial code includes a definition of “family member” as “any other person with whom the minister is in an intimate personal relationship”.

Any finding by the ICAC that Premier Berejiklian had breached the ministerial code of conduct could be politically lethal, provoking demands for her resignation.

Perhaps herein lies the root cause of the current federal government’s resistance to a federal ICAC or its own proposed Commonwealth Integrity Commission having independent coercive powers (search warrant raids, covert surveillance, meta data access) to examine ministerial discretion and to test the application of that discretion against codes of conduct.

Pointedly the current draft Commonwealth Integrity Commission legislation drawn up under the authority of former Attorney General Christian Porter prohibits any “own motion” CIC investigation of ministers and MPs, limiting coercive inquiry only to law enforcement corruption.

The CIC would not be able to investigate retrospectively. There would be no findings of corrupt conduct allowed for parliamentarians or public servants. No public hearings could be held into public sector corruption.

Any evidentiary leads into public sector corruption, provided, say, by an anonymous informant or whistleblower could only be investigated by the CIC where there is a reasonable suspicion that at least one of a number of listed offences has been or is being committed.

Referrals (tip offs) alleging corrupt conduct within the public sector and by parliamentarians is “significantly circumscribed” according to a submission on the CIC draft by the Centre for Public Integrity.

The functions the CIC would be divided into a law enforcement integrity division, incorporating the existing Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity, and a public sector integrity division.

But, please note, nothing has been proposed on constraining ministerial discretion. This is because it is acknowledged that ministerial discretion can be a useful lever of administrative efficiency in bureaucracies often bogged down by discoverable compliance documentation, otherwise known as “red tape”.

Ministerial discretion has been particularly helpful during Australia’s COVID pandemic counter measures federally and in the states and territories.

It is also interesting to note that neither the authors of the Morrison government’s proposed Commonwealth Integrity Commission nor its informed critics of former judges and corruption investigators from the Centre for Public Integrity, other ethicists and integrity advocates are proposing any reform of ministerial discretion. So the issue is about practical, transparent accountability with consequences to drive culture change from its current cynicism to help restore public trust in government.

Attorney General Michaelia Cash, who has replaced Christian Porter, has indicated that the Morrison government is still committed to a federal anti-corruption body.

Hundreds of public submissions are currently being assessed. A total of $106.7 million in “new” funding was allocated for the CIC in the 2019-20 budget and together with the ACLEI’s $40.7million budget any new CIC would have a total staff of 172.

In his consultation paper issued last November Mr Porter attacked Labor and Greens calls for a new integrity body that, he said, would represent “a NSW ICAC on steroids”.

But in an analysis of 18 major submissions on the CIC draft, the Centre for Public Integrity has found “virtually unanimous” opposition to the CIC’s constrained jurisdiction, powers and its unnecessary split up into two divisions.

“No organisation supports the CIC’s referral process and the inability for the public to make complaints. Nine organisations support broadening the definition of corrupt conduct, one opposes. Fifteen organisations support public hearings, one opposes,” said former judge Anthony Whealy QC, chair of the centre.

“The proposed Commonwealth Integrity Commission will not be able to do its job. It will not be able to investigate most cases of corruption, and it will keep everything hidden from public view.”

As things stand at the moment Christian Porter’s proposed CIC model has been judged a whitewash.

Over to you Attorney General Michaelia Cash.

Read more:

https://johnmenadue.com/quentin-dempster-why-cant-we-agree-on-the-powers-needed-for-a-commonwealth-integrity-commission-quentin-dempster/

Read from top