Search

Recent comments

- seriously?...

2 min 20 sec ago - AfD....

29 min 34 sec ago - undesirables...

46 min 7 sec ago - assistant spies......

1 hour 11 min ago - brics.....

4 hours 19 min ago - nuke fukus.....

8 hours 28 min ago - dead or alive?....

8 hours 37 min ago - who what when where?....

10 hours 13 min ago - elon vs kanbra.....

11 hours 7 min ago - tanked think-tank.....

12 hours 8 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

double-speak in the times of forbidden double-entendre...

Marise Payne had been Australia's Foreign Minister for just over two months in early November 2018.

She was just about to head off to China, the first Australian foreign minister to visit in more than two and a half years. The visit was seen as a sign of a thaw in relations between the two countries, in an earlier round of what now seems to be a regular freezing and defrosting of relations.

The ABC's Sabra Lane asked her whether her visit was in any way related to a memorandum of understanding signed between the Andrews Government in Victoria and the People's Republic of China about China's Belt and Road initiative.

"Not in the least," the famously-careful Payne responded. "No, that's a matter for Victoria in that regard.

"We obviously seek opportunities to strengthen engagement with China on regional trade and infrastructure development projects, and that includes the BRI, where those align with international best practices," she said.

"We have a range of agreements and MOUs with China; they govern infrastructure and other cooperation opportunities, and state and territory governments also look to expand those opportunities."

Victoria and the other states, Payne added, "have a variety of similar arrangements with China, and not just with China, in fact, with other countries as well, of course."

Had Victoria consulted with Canberra about the deal? she was asked.

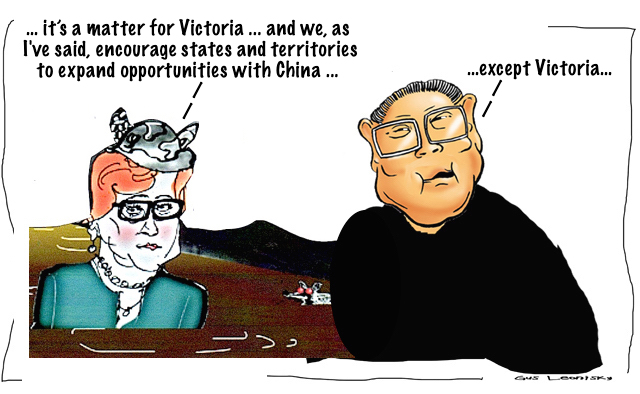

"Oh no, that's a matter for Victoria ... and we, as I've said, encouraged states and territories to expand opportunities with China ... Any treaty-level arrangements, of course, are made at the Commonwealth level, and you would expect that to be the case."

The thing that probably still rankles the PMYes, that's a particularly long quotation for a column. But it's one worth revisiting in the wake of the announcement by Payne and Prime Minister Scott Morrison this week of new laws giving the Federal Government the capacity to vet, and veto, agreements made with foreign governments by states, territories, councils and universities, to make sure they're "consistent with Australian foreign policy".

Nobody missed the point that the Victorian BRI deal was firmly in the frame in this regard.

That was because the equally-new prime minister of November 2018, Scott Morrison, had taken a very different view of the deal to his foreign minister, opining at the same time that he was "surprised that the Victorian government went into that arrangement without any discussions with the Commonwealth Government at all or taking ... any advice ... on what is a matter of international relations".

"They're the responsibilities of the Commonwealth Government and I would've hoped the Victorian Government would've taken a more cooperative approach to that process," he said.

"They know full well our policy on those issues and I thought that was not a very cooperative or helpful way to do things on such issues."

Payne and Morrison's views at the time reflect the difference between day-to-day diplomacy and politics as much as they do questions about when exactly an agreement by a state government becomes a matter of international relations.

They may also reflect the fact that it probably still rankles with the Prime Minister that he was Treasurer — and therefore the bloke with final say over foreign investment decisions — when the Port of Darwin was sold to the Chinese in 2015.

Because the port was owned by the Northern Territory, the Federal Government didn't get a say in it — even though, in an embarrassment for all those involved, it later emerged that the Foreign Investment Review Board and Defence establishments had been consulted on the sale and Defence had not raised any problems.

Why this week, of all weeks?The Prime Minister said this week that the new laws were a reflection of the fact that "we need to ensure that Australia, not just at a federal level, but across all of our governments, speak with one voice, act in accordance with one plan, consistent with the national interest, as set out in Australia's foreign policy, as determined by the Federal Government".

And he is right of course: external affairs are clearly the preserve of the Federal Government under the Constitution.

It's just that the Government chose this week, of all weeks, to announce this concern for all these "arrangements of this nature, of this level" — which Payne pointed out in 2018 were made "regularly with other countries in this region and more broadly" — were alarming enough to provoke an entire new body of federal law.

That would be a week in which he and his government were furious with Dan Andrews and Victoria about letting the coronavirus spread into the community, and was feeling increasingly impotent to direct national affairs as states refused to comply with requests to open their borders.

Clearly, since 2018, the Government's concern about what are seen as China's attempts to influence Australian politics and policy have escalated, as has China's assertiveness in the region.

But given the Prime Minister had these concerns way back in 2018, how come when he finally decided to announce these new laws there were no details of how the scheme would work, no legislation, and no consultation with any of the parties that might be affected by it?

In what may have been a Baldrick moment, someone seemed to decide at the last moment to also include universities in the scheme, a move which had the added political attraction of bringing the Government's alarm — and alarmists — about possible infiltration of our academic sector by China into the frame for good measure.

Of course we don't have detailsExcept the universities have already been brought in from the cold on this issue.

Education Minister Dan Tehan announced the establishment of the University Foreign Interference Taskforce in August last year.

Under the eye of defence, national security and foreign affairs bureaucracies, it developed guidelines to ensure "research, collaboration and education activities must be mindful of national interest".

Then, with no warning and certainly no consultation, the universities heard of the new laws late on Wednesday, after details of them were briefed out to journalists as a 'drop' for morning newspapers and bulletins.

Of course we don't have any details of what is involved, but the announcement suggests an entirely new section of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, full of bureaucrats fastidiously scrutinising literally tens of thousands of agreements signed by state and local governments and universities over the years, disallowing both existing and prospective deals.

The reality, of course, is that the policing of such a system would be much more likely to focus on a few key targets, like the Victorian BRI deal and the Confucius Institutes that operate in the universities.

Then again, like many of the Government's recent announcements, particularly on funding, there is a chance we may hear little more about these new laws, even though a Labor opposition too scared to be baited on anything to do with national security would likely wave them straight through the Parliament.

Laura Tingle is 7.30's chief political correspondent.

Read more:

- By Gus Leonisky at 29 Aug 2020 - 11:51am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

“our free and open society” ...

On July 23, in the midst of the worst pandemic since the Spanish flu ravaged the United States in 1918, Mike Pompeo appeared at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum in Yorba Linda, California, to give his most important foreign policy speech as secretary of state. Standing in the bright California sun in front of Nixon’s boyhood home, Pompeo didn’t disappoint. While praising Nixon’s foreign policy prowess, and particularly his 1972 opening to China, Pompeo issued an increasingly popular cautionary note, while explicitly criticizing the failure of Nixon’s China policy: “The kind of engagement we have been pursuing has not brought the kind of change inside of China that President Nixon had hoped to induce,” he intoned. “The truth is that our policies—and those of other free nations—resurrected China’s failing economy, only to see Beijing bite the international hands that were feeding it.”

Put simply, Pompeo praised Nixon for forging the opening to China, but then criticized the United States for overseeing the rise of a nation wedded to oppressing its own people—and challenging American power. The United States had created a monster. In the years since Nixon’s opening, Pompeo argued, China had exploited “our free and open society,” sent “propagandists into our press conferences,” marginalized Taiwan, “ripped off our prized intellectual property and trade secrets,” sucked “supply chains away from America” and “made the world’s key waterways less safe for international commerce.” The Pompeo charge sheet charted an impressive litany of Trump administration complaints—the most damning being China’s “decades-long desire for global hegemony.”

Pompeo’s speech was weeks in the making and garnered widespread attention—particularly among Washington’s foreign policy elites. Among the most respected of them was Richard Haass, the estimable head of the Council on Foreign Relations. Pompeo, Haass wrote in the pages of The Washington Post two days after the secretary of state’s address, “sought to commit the United States to a path that is bound to fail. It is not within our power to determine China’s future, much less transform it.” The U.S., Haass went on to argue, “should be working with countries of the region to produce a collective front against Chinese claims and actions in the South China Sea; instead, it took three-and-a-half years for the State Department to produce a tougher but still unilateral U.S. policy.”

While neither Pompeo nor the State Department responded to Haass’s article (it would have been unusual if they had), they might have pointed out that the secretary of state’s Nixon Library speech preceded by days a visit from Australia’s top foreign policy officials to Washington as part of the yearly “Ausmin” ministerial consultations—during which Pompeo and his fellow West Point graduate, Defense Secretary Mark Esper, would challenge America’s erstwhile South Pacific ally to join them in confronting China in the region. Pompeo had even coined a name for this campaign, telling his Yorba Linda audience that the U.S. would take the lead in recruiting a group of like-minded nations, which he dubbed an “alliance of democracies.” The meetings, within days of Pompeo’s offering, seemed to imply that Australia would be the U.S.-led “alliance of democracies’” first member.

And so it was that, four days after Pompeo’s address (and two days after Haass published his critique), Esper (the administration’s reputed most senior China expert) welcomed Australian Defense Minister Linda Reynolds at the Pentagon, while Pompeo hosted Australian Foreign Minister Marise Payne in a series of high-level talks at Foggy Bottom. The U.S. rolled out the red carpet for their Australian defense and foreign policy counterparts—complete with a Pentagon color guard, closely coordinated exchanges on issues ranging from public health to intelligence sharing, a high profile State Department dinner, and a carefully choreographed press briefing in which Pompeo was effusive in his praise of the “lively and productive set of conversations” that he and Esper had had with their Australian counterparts.

In all, or so Pompeo and Esper would have the Washington press corps believe, the talks were both substantive and productive—with the U.S. and Australia seeing eye-to-eye on a host of issues, not least of which was the desire of both governments to respond forcefully to what Pompeo described, just days earlier, as China’s “new tyranny.” In fact, however, Pompeo and Esper’s squiring of two of Australia’s most important foreign policy officials not only did not go as well as either had hoped, but was preceded by what one Pentagon official described as Pompeo and Esper’s joint realization that it would be nearly impossible to argue Canberra out of what this Pentagon official described as “Australia’s three no’s”: no to a permanent presence of U.S. troops on Australian soil, no to America’s oft-asserted desire for the construction of a large U.S. naval base on Australia’s western shore, and no to the U.S. plan to position intermediate range nuclear missiles in Australia as a counter to China’s nuclear ambitions.

All of this was entirely predictable. America first mooted the idea of building a large naval base in Australia in 2011, in the midst of Barack Obama’s “pivot to Asia”—what was then perceived as a bells and whistles strategic shift in U.S. military priorities away from the Middle East and the war on terror—and towards a new engagement with Asia. But while the Obama program was touted as a reorienting of American defense and foreign policy priorities, America’s Asia allies, including Australia, were lukewarm, preferring a strategy of engagement with China that included deepening economic, social, and cultural ties, support for the Obama-negotiated Trans-Pacific Partnership (the TPP, which the Trump administration nixed), and the strengthening of cooperative relations through the Association of Southeast Asian Nations—ASEAN.

Additionally, Australian officials have made it clear in recent years that, while U.S. troops are welcome in Australia for training purposes, or as part of joint U.S.-Australian war games, a more permanent presence of U.S. troops in their country is out of the question. The Australians have even made it clear that they remain uncomfortable with 2,500 U.S. Marines stationed near Darwin (on a strictly rotational basis), lest the American presence grow. The same is true for America’s desire to build a sprawling naval base in western Australia, a necessity if the U.S. Navy is to project its reach not only northwards into the South China Sea, but westwards into the Indian Ocean. A 2011 paper on the subject, written by Naval War College thinkers James Holmes and Toshi Yoshihara, landed like a thud with Australian officials, who said that they would agree to the proposition of U.S. military supplies in their country, but nothing more. When Holmes reupped the idea in the pages of The National Interest, last November, Australia’s answer was the same.“Australians pride themselves on their reputation as a dependable ally on the battlefield,” as one Australian official noted recently. “But they are more reluctant to yield up slices of their plentiful territory for foreign military use.” It’s also clear that the American idea of positioning ground-launched, intermediate range missiles in Australia—or anywhere else in Asia—is a non-starter in Canberra, which views the U.S. withdrawal from the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) agreement in August of last year as unwise. The diplomatic equivalent of a cold silence greeted Esper when he mentioned the possibility in a trip to Australia last year, and the chance of doing so now is so remote that it’s not even clear that it was discussed with Australian officials during their Washington visit.

Indeed, as the senior Pentagon official with whom I spoke said in the wake of the Pompeo-Esper meetings in July, U.S. foreign policy experts “are in dire need of sensitivity training on Australia’s long history of serving as a catspaw in big power conflicts.” As a former British colony, Australia was ill-served by a succession of British prime ministers, who used Australian troops as cannon fodder during the Boer War when two of its soldiers (Peter Handcock and Australian poet Harry “Breaker” Morant), were executed by British authorities, and then in World War I, when nearly 9,000 Australians died during the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign. Australians were also rubbed raw by the loss of 15,000 of their soldiers taken prisoner at Singapore after the British had transferred them there, and by what they viewed as their needless sacrifices during the final days of World War II, when the U.S. insisted that Australian troops participate in a series of needless military offensives against Japanese troops bypassed by the Americans on islands in the South Pacific. The result of all of this is that the Australians have proven to be less willing to shape a follow-the-leader foreign policy than at any point in their history—that, for the politicians of Canberra, it is “Australia first.”

In reading between the lines, that became clear in the final press conference featuring Pompeo and Esper with their Australian counterparts on July 26. While the press conference was held to great fanfare at Foggy Bottom, the official communique of the U.S.-Australian meeting was decidedly tipped in Australia’s favor—where Australian talking points took the lead. The lead issue of the joint communique was not China, but fighting the coronavirus, followed by a commitment to the strengthening of “our networked structure of alliance and partnerships,” maintaining a bilateral commitment to “women’s security,” economic empowerment, and recognizing the importance of the Pacific Islands Forum—all Canberra’s foreign policy priorities. The U.S.-Australia response to China then followed, but in terms that seemed dictated by Australia, not the U.S.: with a focus on human rights, Hong Kong, and maintaining ties to Taiwan. Nowhere was there any mention of Australia’s agreement to a permanent presence of U.S. troops on Australian soil, the building of a U.S. naval base on Australia’s western shore, or the positioning of intermediate range missiles in Asia.

While both Pompeo and Esper later hailed the U.S.-Australian meetings as a resounding success, in any other time and in any other administration, the conference would have been adjudged for what it was—an embarrassing failure. Worse yet, Pompeo’s Nixon Library walk-up would have been seen for what it was: a stillborn attempt to birth an American-led “alliance of democracies” focused on confronting China militarily. The message from “down under” is unmistakable: Canberra will continue to partner with the U.S. in building a more secure environment in the Southwest Pacific, but Canberra is not interested in transforming their region into a theatre of conflict. So while Americans are quick to applaud the Trump administration’s “America First” agenda, Pompeo and Esper’s meeting with their Australian counterparts show that two can play at that game—reinforcing what is now becoming all too apparent in the age of Trump: that America’s allies are willing to help the U.S., but only on their own terms.

Mark Perry is a journalist, author, and contributing editor at The American Conservative. His latest book is The Pentagon’s Wars.

Read from top.

See also:

misunderstanding china as a backward country for the last 40 years...and: http://yourdemocracy.net.au/drupal/node/35424

a rocky relationship...

The Democratic and Republican National Conventions are typically an opportunity for US voters to get a sense of what their next president's domestic policies might look like.

But this year they also provided a key insight for China Inc as it navigates its rocky relationship with the US.

Several insiders at Chinese technology firms say have told me that a Joe Biden presidency would be more appealing than another four more years of President Trump - which would be seen as "unpredictable".

And while they think a Biden administration would still be tough on China, it would be based more on reason, and fact rather than rhetoric and politicking.

One thing is clear though: companies on the mainland believe that whoever is in the White House the tough stance on China is here to stay.

Here are three things that are worrying Chinese companies the most about the next US administration - and what they're doing to protect themselves:

DecouplingThis word gets used a lot these days. President Trump and his administration talk about it in tweets and in press statements in relation to China.

Decoupling basically means undoing more than three decades' worth of US business relations with China.

Everything is on the cards: from getting American factories to pull their supply chains out of the mainland, to forcing Chinese-owned companies that operate in the US - like TikTok and Tencent - to swap their Chinese owners for American ones.

Make no mistake, under a Trump administration "decoupling will be accelerated", according to Solomon Yue, vice chairman and chief executive of the Republicans Overseas lobby group.

"The reason is because there's a genuine national security concern about our technology being stolen," he said.

But decoupling isn't that simple.

While the US has had some success in forcing American companies to stop doing business with Chinese tech giants like Huawei, it is pushing Chinese firms to develop self-sufficiency in some key industries, like chip-making and artificial intelligence.

"There's a realisation that you can never really trust the US again," a strategist working for a Chinese tech firm told me. "That's got Chinese companies thinking what they need to do to protect their interests."

DelistingAs part of its focus on China, the Trump administration has come up with a set of recommendations for Chinese firms listed in the US, setting a January 2022 deadline to comply with new rules on auditing.

If they don't, according to the recommendations, they risk being banned.

While a Biden administration may not necessarily push through with the exact same ban, analysts say the scrutiny and tone of these recommendations is likely to stay.

"A Democrat, whether in the White House, Senate or Congress, would have little reason to roll back Trump's toughness on China without some concession in return," said Tariq Dennison, a Hong Kong-based investment adviser at GFM Asset Management.

'"One thing both parties seem to agree on in 2020 is to blame China for any of America's problems that can't be easily blamed on the other party. That's not going to change anytime soon."

Read more:

https://www.bbc.com/news/business-53928783

us military youtube...

US joined a coalition of allies against China After Taiwan Cornered in South China Sea As tensions continue to mount in the waters surrounding the contested islands of the South China Sea, a US navy aircraft carrier conducted exercises in the region on August 17. This came after the Trump administration hardened the US’s longstanding neutral position on China’s maritime claims in the South China Sea The strengthening of the US position on the South China Sea signals an effort to build a coalition of allies and partners to counter and – in Esper’s words “openly compete” with – China.#USAirForce #USNavy #USMilitary #USDefense #DefenseNews #MilitaryNews #Military #MilitaryUpdate #Aviation #FighterJet #AircraftCarrier #MilitaryToday #News #BreakingNews #USMilitaryOperations #SouthChinaSea

See more:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JBnjCpa0pMQ

war games?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SL1ZGwUNblc

the message is simple...

The message is simple: if you don’t stay pure and loyal, you will soon become American fodder…

In China, the ubiquitous Xi Jinping returns under the sign of "purity" and “loyalty"

Propaganda and purges: The Chinese president continues to strengthen his power as the end of his second term approaches. In foreign affairs, he calculates consequences of the tensions with the United States, which promise to be long-lasting.

So far, at this point in their own careers — the second part of their second term — the previous presidents of the People's Republic of China were preparing their succession. Xi Jinping does exactly the opposite. This Chinese president, who ended the constitutional two-term limit in 2018, is doing all he can to consolidate his power ahead of the 2022 Chinese Communist Party (CCP) congress, and beyond.

All summer he has been everywhere. On Wednesday, September 2, the China New News Agency presented today's main news about China on its website. All highlight him. Xi and the Yellow River, Xi and the teaching of political philosophy, Xi and Tibet, Xi and cooperation with Indonesia, Xi and the handing over of a flag to the police, Xi and Morocco, Xi and the economic reform, Xi and the environment, Xi and his expectations of young people...The cult of personality is such that many are starting to think that Xi Jinping could, in 2022, get the title he still lacks: that of president of the CCP, a post that disappeared in 1982.

Is it in his perspective? Since the beginning of July, a new campaign of purges has hit the police, the judiciary and the state security apparatus. In presenting it, the secretary general of the Central Committee for Political and Legal Affairs, Chen Yixin, chose a vocabulary reminiscent of the dark days of Maoism. It's about "educating and rectifying the public servants", "scratching the poison to the bone”.

Chen Yixin, who is being touted as one of Xi Jinping's possible successors, has compared this present purge to the "Yan’an Rectification Campaign” — a grim history. Led by Mao from 1942 to 1944, this campaign — which bears the name of the communist base in Shaanxi from which it was launched — is said to have killed more than 10,000 opponents, real or imagined within the Party, and gave rise to to the cult of Mao's personality.

https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2020/09/02/en-chine-l-omnipresent-xi-jinping-fait-sa-rentree-sous-le-signe-de-la-purete-et-de-la-loyaute_6050639_3210.html

Translation by Jules Letambour. Read from top.

the future of pakistan is with china...

Pakistan's PM: Our economic future is now linked to China

Prime Minister Imran Khan reviews his first two years in office.

Imran Khan was sworn into office as Pakistan's 22nd prime minister in August 2018.

The cricketer-turned-politician promised justice for all and a corruption-free country.

So, two years on, how is the fight against corruption going? How is he coping with the geopolitical changes? Has he turned the economy around? What about human rights and media freedom? And how is he managing Pakistan's response to the COVID-19 pandemic?

These are some of the questions we put forward as Prime Minister Imran Khan talks to Al Jazeera.

Read from top.

the other future...

Cartoon by Cathy Wilcox, SMH, 3/9/2020

Apparently, 87 journalists at the ABC have been made redundant... but this has not made "the news"...

Read from top.

you would end up in prison, like assange...

By Matthew Carney

It was late on a Friday evening and I was about to head home from the ABC's Beijing office when the telephone rang.

On the other end of the line was a man from the Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission.

He refused to give his name but insisted one of the ABC's Chinese staff write down the statement he was about to dictate.

The man told us our reporting had "violated China's laws and regulations, spread rumours and illegal, harmful information which endangered state security and damaged national pride".

It was August 31, 2018, and I had been the ABC's China bureau chief since January 2016, working alongside reporter Bill Birtles.

Three weeks earlier the ABC's website had been suddenly banned in China and ever since I had been pushing for an official reason why. The telephone call came, and there it was.

But the call also marked the beginning of something else: more than three months of intimidation until my family and I were effectively forced to leave China.

They wanted me to know they were watchingI am telling this story for the first time. After my departure from China I was reluctant to report what had happened because I did not want to harm the ABC's operations in China, put staff at risk or threaten the chances of my successor as bureau chief, Sarah Ferguson, being granted a journalist's visa to China.

But all that changed when Birtles and the Australian Financial Review's Mike Smith fled the country this month.

Read more:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-09-21/matthew-carney-foreign-journalist-china-intimidation-birtles/12678610

Read from top.