Search

Recent comments

- rumor....

2 hours 54 min ago - no intelligence....

3 hours 3 min ago - counting chickens....

3 hours 31 min ago - a deal rather than war....

6 hours 59 min ago - made in WA....

8 hours 20 min ago - nuclear sabre-rattling....

12 hours 38 min ago - american gangsters....

17 hours 22 min ago - boiling point....

17 hours 31 min ago - what happened....

1 day 6 hours ago - the empire's democracy.....

1 day 8 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

the false daylight...

“The country was lovely in the spring. The upland were green with tall grass, the ponds were full, and the whole valley bursting into life.”

So starts Thomas Craven on his chapters about American art. His previous chapter had been about “Cubes and Cones” in which he satirically explained how Modernism had destroyed Impressionism and its imitations — and ultimately had destroyed itself — thus the next move had to be a swift and fearless plunge into the reality of life… America, here we come.

Craven commits the “sin” (delusion) of belief that art should be reality — like an image of people dancing in the street. The French had their "Images d’Epinal” showing such “scenes” in a more illustrative naive style. Craven wanted American art to give up the "alien cultural fetishes” and he hoped for the invention of a “native American art". By this he did not mean “native” as “indian” (though he also praised new Mexican art based on cactuses and pots), but as truly American as the Congress building and the Lincoln Monument. The uplift would have to be like Copland’s Appalachian Spring later on, which to Gus seems to have a Sibelius inspiration nonetheless, with not a note of satire in it. One must acknowledge that America was suffering from the Great Depression still when Craven was writing. The American art that rose from the ashes of the stock market crash was a, sometimes reasonable, often poor imitation of Renoir and the French impressionists and expressionists Paris school, but no more than this — except using the American social landscape with the American flag rather than the Seine settings of laced sunbrellas.

Eventually, the American art gave us the Campbell Soup cans of Andy Warhol. American art had been swamped by its rich sister — advertising. There was a fine line between sarcasm, pretend philosophy and money. Art became a valuable commodity rather than an expression of social values as if art censured itself to avoid any acidic social comments contrary to the great American engine thrust — the dollar. In the middle of all this, “Pop Art” had thus sprung more as a distraction than a rabid mirror. A lot of movements came and went. Mr Crapper’s invention worked overtime.

The great energy and flaws of the Paris School of art, which Craven did not like much but recognised as a stepping stone, was eventually replaced in America with facile abstract works of pretty colours to match interior decoration, which would have made a Frank Lloyd Wright spew.

These work sure are pretty, but they represent a lack of philosophical fibre, they represent a lack of idea. I suppose this was the point. One could see a lot of these paintings in the scenes of “Two and a Half men” — at Evelyn Harper's, the brothers' mum’s place. The distance between the crass and the brilliant was very thin. Interestingly, the first painting in Craven's “Modern Art”, whether it was his own choice or that of the publisher, Simon and Schuster, is Montmartre Street by Maurice Utrillo. Utrillo was no Renoir. As explained by Gus in the series from Marcel Duchamp downwards, Utrillo was a drunk who painted “fadasse” (tasteless, spineless) landscapes, under his mother's instruction, from mostly postcards as "he was not allowed out".

In post war Australia, we had the Percivals, the Lloyds and the Ned Kelly Series (1946 onwards) by Sidney Nolan, for whom the imagery was personal rather than social — even if based on folklore and legends of the bush. In Russia, the art had to be social, that of exulting the masses to work together — hammer in hand.

Many of the European artists who went to the US as émigrés ended up producing art like one flips burgers. Even Grosz lost his satirical demons for an unreal “reality”. Schoenberg had to write pleasing music to fill half a room…

It’s a bit as if in order to produce “great art” — art that twists your innards — one needs to be under the stress of a social burden and be reactive rather than be free to produce whatever crap comes to mind, or be under the demand of making sausage rolls on order, from galleries owners — or kings, who will demand glory in fine details on a 20 foot wide painting. The details tell the story of achievements in superiority of a monarch that will tell her subjects to “keep calm and carry on" in the middle of “the panic”.

At this stage art that is visceral is replaced by dull prettyness with precision. Interestingly, Craven did not indulge the surrealists, who were quite out-there when he wrote his book. It’s a bit like a deliberate act of of ignorance. Many French books on modern art do not mention George Grosz or Otto Dix.

Here we must consider the abstractive stylistic visions of the Aboriginal people of Australia. Like in much of the Western art there is some bad, good and some brilliant works. And there is a rich diversity of expression, using traditional styles and adaptations thereof into modern vernaculars. I have already mentioned this a few times in general on this site, but we should look at individual expressions in which there is still a message. Westerners are poor at deciphering the messages or can’t bother beyond the pretty dots and the tonal desert colours. The objects that we’ve made, disappear and are replaced by visions behind our closed eyes — visions that are memories of where we’ve been and where is the next waterhole or such. It’s a journey amongst birds, fish, crocodiles in which powerful symbolism, invented about 50,000 years ago is still strong and abstracted. It’s a language of lines and dots. You won’t see the animals and the plants but you can imagine your journey amongst the stars and under the sun.

And there is the brilliant sarcastic expressionism of someone like Blak Douglass. He is like an Aboriginal warrior who paints rather than fight with a spear, but his comments are on par with those of a Grosz. Blak's black Christ is a mordant. More cutting still, because in Grosz's works we are made aware of a single culture devouring itself. With Blak Douglass’ paintings, it’s about the clash of two cultures — one arrogantly white and one peacefully sniggering as if grabbing the whitefella by the balls. We deserve it.

Welcome to country.

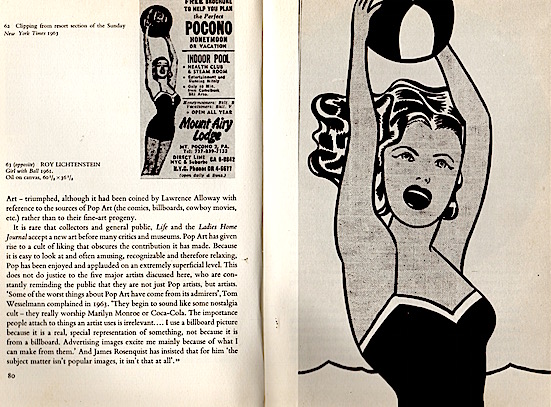

Note: picture at top from page 80-81 of Pop Art by Lucy R Lippard, first published 1966

- By Gus Leonisky at 6 Apr 2020 - 7:32am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

the clown is needed more than ever...

Adam Geczy

‘In the so-called age of post-democracy, of the fizzle-out of the Occupy Wall Street Movement, of corporate megalopolises, the failed ‘hope’ of Obama and now the astonishing rise of Trump, the clown is needed more than ever as a symbol and a cipher of defiance in despair. He embodies an age when idiocy is rewarded, when platitudes are lauded, and the world disordered. At the same time, he is the figure of resistance, as one who fails to crumble through the force of his own whimsy and hysteria, who creates his own world that holds a mirror to absurdity and ignorance.’ – Adam Geczy

Read more:

https://www.artistprofile.com.au/adam-geczy/

See also:

https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/4450/blak-douglas-and-adam-geczy-the...

The Lock Up is a contemporary art space in Newcastle, NSW, located inside a colonial-era police station that was last in operation in 1982. The rare heritage-listed cells and former exercise yard have literally provided a template set in stone for the various exhibitions that I’ve viewed over recent years, many of them engaging with the venue’s site-specific nature. While there is a main gallery, most of the exhibition space is discovered by entering a labyrinth of tiny nineteenth-century holding cells, replete with inmates’ graffiti etched into the walls. Indeed, every time the threshold of the building is crossed you’re guaranteed an eerie confluence of past and present; where art can never be completely divorced from its context. Entering The Most Gaoled Race on Earth, you half expect a sideshow spruiker to shout you in, as if this sorry statistic (per capita the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia are the most incarcerated in the world) is a claim to fame. The carnivalesque is continued as the first in-your-face image, Hungmen, looms large: a bright yellow, canvas banner depicting a black stick figure hanging from a hangman’s noose, the ten letter word underneath reads A-B-O-R-I-G-I-N-A-L.

Artist Blak Douglas described the opening of this exhibition as “the party anyone who has been jailed never had”. By all accounts it was packed, with speakers including local resident Joe Weatherall, brother of Lloyd Boney whose death in 1987 (police stated that he was found hanging by a football sock in a Brewarrina lock up) was one of many which prompted the 1989 royal commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody.

the brett whiteley dream...

Thousands of words are written every day about the bedlam that is American politics. And why not? So much of this period seems extreme and alarming, and it’s hard to turn away. There was another time, though, half a century ago, when a succession of calamities was tempting even the most sober of analysts to predict the collapse of the republic.

In 1968, America was a country divided. The casualty rate was rising sharply in Vietnam, and public opinion was turning against the war. Back home, signs of violence were all around. In April, Martin Luther King Jr was shot dead in a Memphis hotel, resulting in riots nationwide. Two months later, forty-eight hours after Valerie Solanas shot Andy Warhol in New York, presidential candidate Robert Kennedy was shot dead in Los Angeles. Reports of his death prompted the playwright Arthur Miller to write an anguished piece for The New York Times. ‘Robert Kennedy’s brain received only the latest fragment of a barrage as old as this country’, Miller wrote, and he invoked the assassinations of King, Lincoln, Garfield, McKinley, John F. Kennedy and Medgar Evers to emphasise his point. ‘Either we begin to construct a civilization, which means a common consciousness of social responsibility, or the predator within us will devour us all’.

A more pronounced denunciation came from the Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko. His poem, also a response to Kennedy’s death, was called ‘Freedom to kill’. It was first published in Pravda, then reprinted in The New York Times on the same day as Miller’s piece. ‘You shoot at yourself, America’, Yevtushenshko wrote, and his words burn with doom even to this day:

The stars

In your flag,

America,

Are like bullet holes.

Brett Whiteley was in his twenties, living and working in Manhattan, when all this madness was taking place. He had found a vacancy inside the city’s great temple for free spirits, the Hotel Chelsea – the penthouse, no less – and was working from a studio nearby. Also with him in New York were his wife Wendy and their daughter Arkie.

Whiteley had travelled to the United States on a Harkness Fellowship the previous year. Before then, he had been living in London for seven years, enjoying a remarkable run of success. Back in 1961, the young painter from Sydney had been the star of Bryan Robertson’s Australian exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery; one of his pictures, an earthy abstraction, had even been bought by the Tate, making him the youngest living artist to have work purchased by that gallery. He went on to represent Australia at the Paris Biennale, mixed with the cultural establishment of London, and had his work featured as part of Whitechapel’s ‘new generation’ of British artists. But just as London had once beckoned from Sydney – the promise of a creative metropolis, its energy impossible to resist – Whiteley soon found himself yearning for New York, his logical next step.

https://ashleighwilson.com.au/The-American-Dream

society

Society (1964) by Peter Saul

Peter Saul (born August 16, 1934) is an American painter. His work has connections with Pop Art, Surrealism, and Expressionism. His early use of pop culture cartoon references in the late 1950s and very early 1960s situates him as one of the fathers of the Pop Art movement. He realised about 800 paintings during his career.[1]

Read more:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Saul

In 1966, Peter Saul went to a protest in San Francisco. He wore a suit and a tie so he wouldn’t get arrested – and it worked.

“People were getting punched to the ground around me, but nobody would touch me, I looked proper,” he said to the Guardian. “Maybe they thought I was an FBI agent, or something. It was dangerous to protest the Vietnam war, but I didn’t get into much trouble.”

Where he did cause trouble, however, was on the canvas. For over 50 years, Saul has focused his art around satire; painting ghoulish politicos, corruption, racism, greed and violence. All this and more is on view at Saul’s new retrospective at the New Museum in New York, where over 60 paintings are on view until 31 May in Peter Saul: Crime and Punishment, a bold testament to political pop art.

“When I do political pictures, I don’t want to end up in a responsible position where my art is backing up some attitude,” he says. “It has to be modern art, trouble causing.”

Saul got into painting in 1960 while living in Paris with cartoonish works of dogs and supermen alongside phrases like “Crime doesn’t pay.” After returning to America in 1964, he squared in on the Vietnam war.

“I just got the idea from reading the newspaper,” said Saul, shrugging. “I don’t think the war was a good idea; there was strong negative feelings about artwork featuring the Vietnam war. Protests were on the streets, not dealing with one’s artwork.”

In one, Vietnam from 1966, soldiers torture a crew of floating communist superheroes, while in another, GI Christ from 1967, a military chief is elevated to god-like status. In Pinkville from 1970, an American soldier destroys everything in his path as he stomps through Saigon.

Read more:

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2020/feb/19/pop-art-painter-pet...

the birth of trump by gus rubensky...

and guess what?....

Art is a funny thing. It lies. Art hides the truth... Even at its most serious poignant expression, the stylisation of the emotions is only going to last a moment, until we go back to our default position: a blank space in search of food and comforts.

We use art to motivate our greater self with hope but the mechanics of such has got ropes, painted sceneries on flats, like a set change on stage.

This morning, William Murchison at The American Conservative, tells us "With some relief, I returned to the subject I previously had in mind: contemplation of Norman Rockwell."

Gus remembers those scene in our family. The turkey was a puny chicken (mostly an old cock that had been boiled forever), the drapes dated from Napoleonic times and the table did not have a table cloth. The plates were made from red clay... The church bells were ringing, warning us of the Prussian invasion.

The illusion of the Four Freedoms rested on the hidden fact that somewhere someone had to be conquered in order to bring our bourgeoisical peace.

United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt on January 6, 1941, in a State of the Union speech, presented the Four Freedoms that people "everywhere in the world" ought to enjoy:

Freedom of speech

Freedom of worship

Freedom from want

Freedom from fear

Roosevelt delivered this speech eleven months before the Japanese attack on US forces in Pearl Harbor that caused the United States to declare war on Japan, on December 8 1941.

This speech was largely about the national security of the United States and the threat to democracies facing a war waged across the continents in the eastern hemisphere. In the speech, Roosevelt broke the "tradition" of United States non-interventionism, as he outlined a role for the US in helping allies engaged in warfare.

And we're back to square one...

Freedom of speech

Yes we know where this goes, Mr Murdoch et al...

Freedom of worship

This is important as long as you do not worship socialism... We'd rather you be a Allah fanatical terrorist than a Corbyn or a Bernie...

Freedom from want

This gets complicated: the turkey comes from a hormone inducing intensive GM farm, for profits, etc and in the next frame following this idyllic Rockwell painting, young Rob is dying in a mosquito-infested swamp on a tropical paradise fought over by competing armies. He does not know if it's the bullet in his leg or the malaria that is making say: "Mama", before his last breath...

Freedom from fear

In this epoch of coronaviruses, we should now know where this leads. If you don't don't fear and don't stay at home, the police will take you away...

Read from top.

there's poetry in them economics...

"The only two pursuits worthy of a gentleman are war and poetry”. So had famously said Ford Madox Ford who late regretted... “I think we may leave out the war."

Ford Madox Ford (Joseph Leopold Ford Hermann Madox Hueffer (1873 – 1939) was an English novelist, poet, critic and editor of the journals The English Review and The Transatlantic Review that were important in the development of early 20th-century English literature.

Ford is remembered for his novels The Good Soldier (1915), the Parade's End tetralogy (1924–28) and The Fifth Queen trilogy (1906–08). The Good Soldier is frequently included among the great literature of the 20th century. Everyone (nearly) has forgotten it…

So why should we indulge in finding out a bit more about this “personality” — the “celeb amongst literary "celebs" in the 1930s? Will we remember Cardi B and her boomdiboom songs? Enters someone called F S Flint… In 1916 Flint was described as having "the gift of artistic courage clothed in beauty which will help build the poetry of the future". Flint himself, humbly considered his cadenced form to be a return to the real tradition of English poetry such as Cynewulf, one of the pre-eminent figures of Anglo-Saxon Christian poetry of the 9th century, in the 'Riddle, The Nightingale’.

By the 1930s Flint moved away from poetry, towards economics — working for the Statistics Division of the Ministry of Labour writing that "the proper study of mankind is, for the time being, economics". Flint published an article entitled The Plain Man and Economics in The Criterion in 1937. For a while, he had become a spokesman for Imagism, its methods, concentration and clarity… Imagism was a loose movement, including Ford Madox Ford, in early-20th-century Anglo-American poetry that adopted precision of imagery and concise language — not very well suited for tortuous dubious economic theories. Imagism has been described as the most influential movement in English poetry since the Pre-Raphaelites…

There is good art and bad art... But then who are we to decide? Can bad plagiarism become a revolution? Can a pedestrian painting become a great painting? Can the Pre-Raphaelites be masters?

One the most atrocious piece of English art, an excruciating Pre-Raphaelite religious work, is called The Light of the World, painted by Holman Hunt.

"Altogether the picture is a failure…” wrote a critic after a massive dump on the piece...

It was such a failure that The Light of the World became the most popular religious painting ever reproduced. There are so many reproductions of the said work in so many houses, that it defies any understanding of the meaning of art.

But we all know (we all should) what Modernism eventually did to the Pre-Raphaelites… though some shameless American artists went back to it under the guise of Neo-realism with cityscapes rather than country bucolic scenes… We also know that Nazism mixed some neorealism with neo-idealism. No wonder the meaningless abstract blob(s) on canvas became the major norm after WW2, to stay clear of this horror.

The relationship between F S Flint and Ford Madox Ford were cordial enough, but FMF did not like Flint to turn up at his precious afternoon tea parties. Ford Madox Ford organised tea parties for women exclusively — women, seated on sofas and armchairs, who drank every one of his words from his philosophical discourse, interspaced with his snorts and sniffs. Ford got pissed-off when Flint came in once (probably to annoy Ford), and the Parisian salon scene was a bit like two cocks fighting to the death in front of the ladies. Not quite.

Flint had arrived somewhat pissed, or inebriated with a few aperitifs under his belt, while the drink of the Ford tea parties was exclusively … tea. This arrival annoyed Ford. Not only that, Flint flippantly insisted that French be spoken exclusively considering they were in Paris. Ford blew up:

“For God’s sake, Flint, remember that you are an Englishman and a gentleman!”

Ford had a bad habit of snorting and sniffing with his mouth drooping openly. Flint mock him as he departed… Ford always embellished his own life with entertaining invented lies. Flint and other of his friends — though Ford Madox Ford was relatively lonely — liked him for that — or despite that.

And so the English language improved… or not.

Read from top.