Search

Recent comments

- grey is dirty....

2 hours 32 min ago - scholz out.....

5 hours 7 min ago - let's say....

5 hours 23 min ago - pentagon purge....

5 hours 48 min ago - gimmicks....

6 hours 1 min ago - scrambling....

6 hours 5 min ago - in a hurry....

8 hours 4 min ago - killing brics?.....

10 hours 23 min ago - losing position....

10 hours 31 min ago - surrender....

11 hours 14 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

art in the days of covid19 contagion and of the need for savage satire...

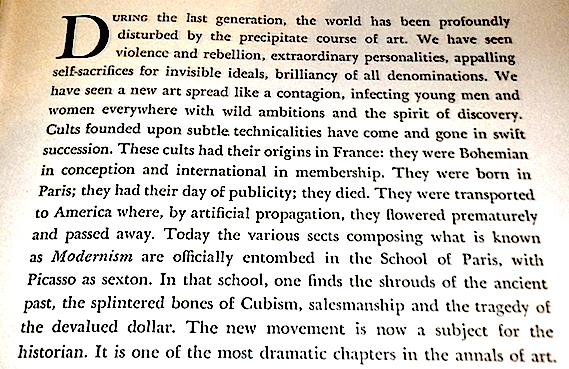

This is an introduction written by Thomas Craven in his book, "Modern Art, the Men, the Movement, the Meaning” published in 1934. It may as well be written yesterday, today and tomorrow.

Let’s make a general statement that in this historical past, the Men encompassed the Human, including Women. The book is a transition between the European arts that bloomed like a million weird wildflowers in Paris and art in the New World which soon developed a “snob spirit”, before finding its own loose footing, especially in architecture with Frank Lloyd Wright. Yet, despite FLW's revolution, and with his house, Taliesin twice burned by fire, we still live in small getting smaller shoe boxes.

During COVID-19 — "In this unprecedented moment, our global community is collectively looking to nature, architecture, culture, and agriculture for new sources of inspiration, healing, and reflection. As a starting point, we invite you to take a virtual tour of Taliesin"… Yes the new art has turned to the sweet pixels, and some in 3D, transported at the speed of light to all corners of the planet "for healing". Artists should never heal...

By chapter 19, the last, exploring Mexican art in the USA, Craven return to art as propaganda, history of the social problems, "freedom of the artist” and "art returning to the people”. All fascinatingly compact observations regarding the social distancing we’re experiencing today — especially the zillion art styles which have basically fallen between cracks, the bland art for art’s sake where every artist is a movement of loneliness and blah repeats.

Amongst Craven’s sharp observation that included the “wild animals” such as Gauguin’s art tattooed with savagery and recognising "the absurd praise of Matisse", there is a, now possibly forgotten, great study of George Grosz… On this site we’ve touched on this subject of degenerate art and Grosz imagination which was spurred by massive satirical and often sad interpretations of his observations of what was sadly behaving with vacuous self-importance. Grosz "Daum marries her pedantic automaton” (Berlinische Galerie) is a “futurscope” of our sex robots. Ecce Homo is the anatomy of degradation and stupration — of rape. From the café to the brothel, as far as Grosz was concerned, everything happened in public, like in Bruegel paintings.

George Grosz did not dwell on his participation in WW1. He did not apologise nor had any regrets. The Great Shambles wounded his spirit that never healed. He was opposed to war — not as a pacifist, nor as an unfit disabled, not as a prophet of the oncoming calamity for the human civilisation. He loved humanity and was for the preservation of German ideals. He was discharged and condemned several times. Unlike Otto Dix, who got the Iron Cross (second class), Grosz got a "certificate of shame", of good health on his first discharge. He wrote and published poems of fleeting images without syntax nor continuity — on the world reeling in a dance of death — a jazz war dance of madness and desolation. But it was his pictures that took Germany by storm.

At 23, he was recognised as the most powerful artist in Germany and one of the most hated men. His later social studies would make you chunder. But his war pictures will “turn your soul, revolt and sicken and exalt you, and leave you wondering how an artist of such implacable bitterness could pause long enough to control his emotions. Grosz fought against war with a weapon more deadly than the sword; and his conception of the crucified Christ wearing a gas-mask condemned him to the firing squad. The young Catholics and Quakers rallied to his defense, and the war lords mercifully transferred him to the front-lines trenches, trusting the French sharpshooters to do their duty."

Grosz portfolio of war action have thus become permanent records of the social animal debauched by war into the social brute.

After WW1, "I was romantic again… I believed in such forbidden metaphysical concepts as Truth, Justice and Humanity — these in spite of the Versailles Treaty. I had no economic program and no party affiliations, but my leanings were towards the extreme left. It was soon obvious, however, that nothing would be changed, or more exactly, improved. I had no faith in the Royalists and none in the Fascists, and I attacked both with all my strength, with an old skepticism sharpened by the war."

Grosz and other young German artists promulgated a semi-artistic nihilism. Influenced by Dadaism — the practical joke of defeated artists, who, instead of committing suicide, ridiculed all artistic and humanitarian efforts — Grosz ferociously turned against the order of things.

“We were deadly serious; we had no humour — and what self-respecting man could have laughed at our country, bleeding and beaten, the spoils of soldiers and hypocrites? We had lived through the war; we had no hope; we were against everything. We would scrap the past; we had no tears for Greece, and none for our Gothic ancestors; we did not believe in art for art’s sake, or Germany for the warrior’s sake.”

Many thoughts and quotes collected from Thomas Craven book, "Modern Art, the Men, the Movement, the Meaning”

Born Georg Ehrenfried Groß (1893 – 1959), Grosz immigrated to the United States in 1933, and became a US naturalised citizen in 1938. Abandoning the style and subject matter of his earlier work, he exhibited regularly and taught for many years at the Art Students League of New York.

George Grosz made this self-portrait following a visit to his native Germany in 1936. Grosz shivers in the shell of a ruined building, replaying images in his mind, which we see behind him. During his return trip, Grosz witnessed the gravity of Nazi persecution in his home country, and he made this image to express his anxiety about the situation. He was haunted by what he saw, and he felt visited by premonitions of the future — World War II.

Interestingly, the satire and the savagery of his earlier work had vanished — replaced with direct angst and despair. He reflected on the impulse behind such different images. “I could not explain exactly what was really troubling me. But after I had returned to the States, my paintings became prophetic. I was compelled by an inner warning to paint destruction and ruins; some of my paintings I called ‘Apocalyptic Landscapes,’ though that was quite some time before the real thing took place.”

"My Drawings expressed my despair, hate and disillusionment, I drew drunkards; puking men; men with clenched fists cursing at the moon. ... I drew a man, face filled with fright, washing blood from his hands ... I drew lonely little men fleeing madly through empty streets. I drew a cross-section of tenement house: through one window could be seen a man attacking his wife; through another, two people making love; from a third hung a suicide with body covered by swarming flies. I drew soldiers without noses; war cripples with crustacean-like steel arms; two medical soldiers putting a violent infantryman into a strait-jacket made of a horse blanket ... I drew a skeleton dressed as a recruit being examined for military duty. I also wrote poetry.”

Note:

Thomas Craven (January 6, 1888 – February 27, 1969) was an American author, critic and lecturer, who promoted the work of American Regionalist painters, Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry and Grant Wood, among others. He was known for his caustic comments and being the “leading decrier of the School of Paris.”

Read more:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Craven

- By Gus Leonisky at 5 Apr 2020 - 7:43am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

the mistakes of the past...

According to Gus, when we abandon the savage satire for serious images of despair, this is a sign we are getting closer to repeating the mistakes of the past...

Almost 80 years after the outbreak of World War II, it is worth remembering two German artists whose work was dedicated to the fight against fascism and war. They are the painters Otto Dix and George Grosz, who died fifty and sixty years ago respectively this month.

Otto Dix (1891-1969) was an uncompromising fighter against imperialist inhumanity. Even before the outbreak of war in 1913, he had painted “Sunrise,” a dark ironic contrast to van Gogh’s “Cornfield with Crows.”

Between 1929 and 1931, Dix created his main work, “The War.” (See main photo, above.) It was a triptych in an old masterly painting technique and form originating in Christian art: Three painted panels attached together and more commonly used as an altarpiece depicting the crucifixion in the center panel, with associated figures or scenes in the wings. Dix’s triptych is an urgent warning of the horrors of annihilation.

On the left side panel, an endless row of soldiers marches into battle in the early fog and under a blood-red morning sky. The light of the “sunrise” is reflected in the helmets. Only one face can dimly be made out; the others remain anonymous and thus stand for all. Hundreds come from a great distance toward the observer, turn and move away again into the distance. This V-shape with the reversal point at the viewer is extraordinarily effective in its use of space to convey an infinite number of helmets and weapons. The two men at the center of the picture carry kitbags, one turns to the other and an eye is recognizable. In addition, a boot and a water bottle are clearly visible, individualizing these soldiers somewhat.

Using the triptych’s inherent reference to Christ’s crucifixion, the left panel alludes to the scene of Jesus carrying the cross. Like him, the soldiers carry their own weapons of death. However, unlike the middle section, the left scene has a certain order and the soldiers are distinctly human.

This contrasts sharply with the frightening depiction of the central panel. Little that is human is perceptible anymore. Where the viewer expects Christ on the cross, instead at the center top of the picture is an impaled skeleton, with its gaping mouth and pointing finger, as if attempting to warn us. The boot preserved on the skeleton links it to the soldier and to the boot hanging from the kitbag in the left panel.

The bony finger points to a crater-like landscape and ruins in which there is no life. People, town, and vegetation are destroyed. The finger of the skeleton also points to the dead man, whose perforated legs protrude and clearly allude to the crucified Christ. He is turned upside down, thus ironically reinforcing the image’s indictment. Most of the central panel depicts intestines and dismembered people. Neither sandbags nor a gas mask were able to prevent death. This central scene of horror inexorably reveals the nature of war.

On the right panel, a soldier whose face bears the features of the painter drags a wounded man from the murder zone; another survivor also crawls out of the inferno. They no longer wear helmets or uniforms; they do not notice the corpse over which they move. A charred tree trunk crosses this panel and, to remain with the idea of the crucifixion, this echoes the taking down of Christ from the cross. Again, Christ is identified with the soldiers.

The burial of Christ is often depicted in the predella, the lower part of the triptych. In the interpretation of this picture by Dix, opinions differ as to whether the soldiers depicted are asleep or dead. In my opinion, bearing in mind the clear allusion to the depictions of Jesus on winged altars, these soldiers are dead. The one in the foreground with his blond mustache resembles the barely visible soldier’s face in the left panel. It almost seems he is sleeping, his head resting on the kitbag, but his uniform has two bullet holes in the chest. So, despite his calm appearance, we must assume he is dead. The eyes of those lying next to him are bandaged, which in turn de-individualizes them. The last soldier has no boots—dead soldiers often had their boots removed by the living soldiers for further use. This had already been hinted at in the left panel with the single boot hanging from the kitbag as well as the boot on the skeleton in the middle picture. Additionally, there are already rats at the feet of the dead. A blood-red shroud is attached to a very low ceiling, evoking a claustrophobic, sarcophagus-like box containing the dead. The straw in the front right corner of the predella is a final reference to the barn where Jesus was born. Here now lie the victims of “The War.”

The art of Dix’s contemporary George Grosz (1893-1959) was also of great importance in the 1920s. The Soviet revolutionary and writer Ilya Ehrenburg wrote about George Grosz: “Germany at that time found its portraitist in George Grosz. He depicted the racketeers with sausage-like fingers. He showed the heroes of a past and a coming war, haters of humans draped with iron crosses…. Yes, he dared to show privy councilors naked at their desks, dolled up fat little dames, gutting corpses, murderers carefully washing their bloody hands in a basin…. In 1922 it appeared like fantasy, in 1942 it became routine.”

George Grosz’s milieu was the city of Berlin in the 1920s. Here, he observed the world of parasites, war profiteers and racketeers, whores and drunks. He painted the amorality of an obsolete society, as well as the victims of the ruling class.

One example is his painting “The Agitator” (1928), in which Grosz warns against the rising Nazis. The heart of the agitator is emblazoned in the colors of the empire—black, white and red. He is decorated with medals and the Iron Cross. The swastika on the tie knot looms ominously right in the center of the picture. While the applauding bourgeois men with their well-fed faces and hands are still relatively realistic on the lower left side of the picture, they become increasingly grotesquely distorted and gaudy on the right. Central to the painting is the ridiculous agitator himself, with a truncheon over his arm, a distorted face, his right hand raised as if taking an oath, and surrounded by the tools of his “trade”: the megaphone, a sports rattle in his left hand, the marching drum and the gramophone all provide background noise. Even bigger is the saber, which hangs from under his little coat. Above his head is a black, white and red dunce’s hat with German oak leaves. Beside his spurred foot is a poster bucket. Above the agitator floats the male Promised Land of roasted chickens, wine and faceless naked women. On the upper left, the oversized laurel-crowned soldier’s boot and a dark fortress form a contrast to this paradise. The former soldier, decorated with the Iron Cross, seamlessly transforms into a Nazi to the applause of the bourgeoisie. Grosz recognized this early on and communicated it.

Read more:

https://www.peoplesworld.org/article/the-anti-fascist-art-of-otto-dix-an...

Grosz "Daum marries her pedantic automaton” (Berlinische Galerie)

George Grosz made this self-portrait following a visit to his native Germany in 1936. Grosz shivers in the shell of a ruined building, replaying images in his mind, which we see behind him. During his return trip, Grosz witnessed the gravity of Nazi persecution in his home country, and he made this image to express his anxiety about the situation.

Between 1929 and 1931, Dix created his main work, “The War.”

the elegant savage satire…...

The Gonzo Weimar Germany of George Grosz.......

However, Grosz’s most powerful works are perhaps not the ones that reflect his personal repugnance of morally degraded elites but the ones in which his sharp eye and pencil capture the workings of a historical process. In 1923, ten years before the Nazis rose to power, Grosz drew a caricature of Adolf Hitler in a furry shift and a necklace of teeth, contrasted with a facial expression of a bitter, deeply offended little man, an obvious misfit for the role of a dignified heir of the great German myth. Another visionary drawing that even today could easily be seen as offensive by right-wing Christian fundamentalists depicts the crucified Christ in a gas mask and combat boots.

Grosz had to withstand fierce public obstruction for his art. His alarming critique of right-wing nationalist and militarist politics was largely perceived as hyperbolic and dismissed as both anti-German and anti-Christian. Grosz received personal threats and legal accusations of blasphemy.

If judged by Grosz’s works, the Weimar period was exclusively populated by ugly men and women indulged in an endless carousel of greed and lust.

It was not just political art however. As the chaos of the Weimar period heated up, Grosz grew more and more disappointed in communist politics at large. The biggest bummer for him was a six-month tour of Soviet Russia in 1922. In his autobiographical account of that trip, almost as bitter and dismissive as his early caricatures, Grosz draws a discouraging and gloomy picture of both the “ruling” masses of workers and peasants and their revolutionary leaders. Grosz also finds no inspiration in Soviet revolutionary art. The Proletkult seemed to him a vulgar Marxist misunderstanding of the nature of artistic talent, which he believed was a deeply ingrained and highly individual quality that could not be nurtured by the social environment. In constructivism, he only saw the dehumanizing cult of machinery and mechanization.

It should be said though that his account of the Russia trip first appeared in 1955 and might rightly be considered an attempt on Grosz’s part to fit into the mainstream of American life at the time. In 1933 shortly before Hitler came to power, Grosz left for New York, where he was offered a teaching position. This timely offer did not only save his life but promised a new beginning. Grosz hoped to find new impulses for his work and finally “move away from hatred to love” on US soil.

This did not happen. A notorious critic of German nationalism, who anglified his first and last name as an antipatriotic gesture, Grosz found himself culturally uprooted in the United States. In art, his figurative style contrasted with the era’s dominant abstract expressionism propelled by his more successful fellow Europeans. He wanted to become an American illustrator, but his over-the-top style was a poor fit for commercial print media. In 1959 Grosz returned to Berlin, commenting that his American dream turned out to be a soap bubble. A few weeks later, he slipped on the stairs of his apartment after a night out with friends. He never regained consciousness and died of heart failure the same morning.

During one of his trials for blasphemy, Grosz explained himself in the following way: “When the times are very troubled, when the foundations are shaken, the artist cannot stand aside, especially not the talented artist with his greater sensitivity. That is why, without wanting to, he will be political. . . .”

One should be wary of drawing historical parallels to understand the current moment, but our times seem to be no less troubled than those of Grosz. What it means to be political for an artist and intellectual today is something that we have to figure out for ourselves, and it is definitely not Grosz’s aesthetics that we can turn to for inspiration. It is his life. Strange enough, both the smashing class hatred of Grosz’s early art and his deepest personal disappointment with the progressive politics of the time seem equally relatable today. All of us should probably be prepared to embrace a similarly contradictory path, filled with bitterness and pain, and to pick up the fight where Grosz had left it, with a humble hope that we will be slightly more successful in it than he was.

READ MORE:

https://jacobin.com/2022/09/weimar-german-george-grosz-caricatures-politics

READ FROM TOP.

REPEAT:

According to Gus, when we abandon the savage satire for serious images of despair, this is a sign we are getting closer to repeating the mistakes of the past...

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW..............