Search

Recent comments

- the fallout....

7 hours 39 min ago - meanwhile....

7 hours 57 min ago - extortion....

8 hours 20 min ago - death wish....

8 hours 24 min ago - heroes....

8 hours 57 min ago - joining fools....

9 hours 16 min ago - humanely....

9 hours 23 min ago - putin's pudding....

9 hours 32 min ago - hungry war.....

9 hours 44 min ago - EU panics....

9 hours 49 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

of an opportunistic nature...

An article in The Guardian is bordering on the ridiculously Anthropomorphic… Gus counters with the concept that nature does not send messages. Some of nature's "elements" react to change in opportunistic manner or in other way such as extinction, with no “message” intended. We interpret what we observe after having dished our rubbish, in order to make sense of our senselessness and carelessness.

An article in The Guardian is bordering on the ridiculously Anthropomorphic… Gus counters with the concept that nature does not send messages. Some of nature's "elements" react to change in opportunistic manner or in other way such as extinction, with no “message” intended. We interpret what we observe after having dished our rubbish, in order to make sense of our senselessness and carelessness.

--------------------------

Nature is sending us a message with the coronavirus pandemic and the ongoing climate crisis, according to the UN’s environment chief, Inger Andersen.

Andersen said humanity was placing too many pressures on the natural world with damaging consequences, and warned that failing to take care of the planet meant not taking care of ourselves.

Leading scientists also said the Covid-19 outbreak was a “clear warning shot”, given that far more deadly diseases existed in wildlife, and that today’s civilisation was “playing with fire”. They said it was almost always human behaviour that caused diseases to spill over into humans.

To prevent further outbreaks, the experts said, both global heating and the destruction of the natural world for farming, mining and housing have to end, as both drive wildlife into contact with people.

They also urged authorities to put an end to live animal markets – which they called an “ideal mixing bowl” for disease – and the illegal global animal trade.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/25/coronavirus-nature-is-send...

-------------------

Gus:

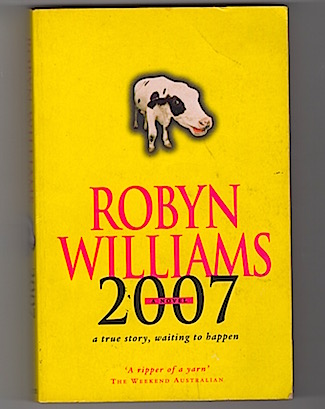

No message intended by nature, unless you read the fiction book by Robyn Williams, 2007, a true story waiting to happen. This excellent work, published 2001, deals with animals consciously revolting against humans — and using all kind of tricks, within their capabilities, to achieve their aim. The book tells of many anecdotes of animals, from monkeys and cattle to ants, decidedly distracting humans into changing their generally nefarious purpose…

By the end of the book, as the captain of a whaling ship is about to capture a humpback, a flock of albatrosses “attacks” the ship and with all his visual and navigation instruments now useless, the captain abandons the chase… The whaling boat is decommissioned and refitted as a cruise ship. Her former captain becomes an ornithologist… Great sense of satire, here...

Lovely. It’s happening. Nature is like fame. it’s often opportunistic. It finds a niche (in a very complex molecular adaptation to change) and fills it but unlike human delusive behaviour (we believe in godot, don’t we?), in nature, distances are mostly respected. The new zoos tend to account for this habitat necessity, within limits of our "generosity" towards the animals. Nature is ad hoc. Humans have develop the great art of stylistic delusions, in which we mistake our existence as godly manipulations of stuff.

Presently the Great Barrier reef is experiencing a major partial bleaching. The third one in five years. This isn’t nature committing suicide to annoy our tourism industry which is now kaput for other reasons. No. We should scientifically recognise that human activity has changed the environmental factors beyond the reef's survival. But our own pride in our worth — and may I add some stupid pseudo-scientists who are contrary polemicists for "no reason" — that we measure in cash is holding back our understanding. Politically, we’re dumb. Psychologically we’re deficient.

Our only defence is often hubris and deceit. These have been our salvation in our checkered evolution. The truth hurts. Thus we pin our troubles on others mistakes, as well as blame “nature”…

China has put an end to live animal markets. We laughed (or marvelled) at the Chinese building a massive hospital in under a week and placing a city of 11 million people under quarantine.

Some of our “journos” (shit-opinionators) like Tim Blair, blasted the Chinese for not telling us straight away what was happening — especially when “one of the doctors was trying to warn the world, but the authorities shut him up.".… Several things to consider: the official line — still believed in the West — is that the virus jumped from pangolins to bats then to humans. By January, most of the western scientists knew something like SARS, possibly worse, was coming... We laughed, then we blamed the Chinese.

Was the "doctor" trying to tell the rest of the world that a virus had escaped from the Wuhan biolab or that it had managed to jump two nature strips to go across the road? It would take more than three weeks of analysis to determine that the virus originated in pangolins — unless someone knew about this a-priori (some people did — see following article). So the Chinese were not so cagey as we think, but they had to know "for sure" what was was happening, where the virus "had come from", that the virus was dangerous, while planning an efficient defence system.

Our reaction was woeful. We closed the barn doors after the horse had bolted. Now we’re in “isolation” which is more like “desolation”. We fought over toilet paper rolls and no matter how Mr Leonisky can make cartoons about this, it shows the extend of our very tragic unfunny dumbness...

Imagine: no flowing water in rivers = fish kills… Environmental factors variations, some natural, some human induced. What proportion? We need to investigate without fear nor favour...

So, this article in The Guardian could be seen as designed to make us forget the MANY biolabs where dangerous pathogens are being manufactured for warfare as offensive weapons — and defensive weapons by developing antigens. Even if most of the biolabs are not designed for warfare, they deal with very nasty viruses and microbes.

We are told by this Guardian article that 75 per cent of all emerging infectious diseases come from wildlife... Hum? This statistic is a bit too neat. The reality is that 86 per cent or 43 percent would be as valid. We don’t really know, apart from a few cases such as the swine fever and the bird flu. What about the rest? Many are human diseases that evolve as we evolve, in our general behaviours. A lift packed with people is like a petri dish for the flu, in the flu season. A plane with one sick person can result in half the passengers carrying the germs. Some people will resist the infection better than others. We know the drill. We need to isolate, but how many people with the flu have gone to work in an office, because they can’t afford being sick? How many people died from the flow on from this?

The social distancing rule is the only way to deal with contagion. But for how long? Now, the trick of governments is to also throw cash like burley to fish in a pond or corn grains to chooks in a yard. It’s the bum rush. Some will get a lot, others will get none. We know.

By and large, infections by pathogens can develop quickly when the normal distance between individuals of species is reduced by artificial means such as farming. Same for humans. There are spacial limits and social limit at which we start feeling uncomfortable.

Place a family of 15 persons in a small room with no exit, and traumas are likely to happen, Physically and psychologically, very quickly… Purpose will become absent. We need space to be active. We need activity to be alive. Nature is the same. This is why we should, our government should anyway, have banned intensive herding such as chicken, pigs and other animals that need space. Some animals will naturally stay in flocks, but they usually keep their individual distances, and the flocks have a natural extend in relation to the availability of food, such as grass.

We are part of nature. Nature is a protein soup in small packets, with sugars and fats added.

“There are too many pressures at the same time on our natural systems and something has to give,” she added. “We are intimately interconnected with nature, whether we like it or not. If we don’t take care of nature, we can’t take care of ourselves. And as we hurtle towards a population of 10 billion people on this planet, we need to go into this future armed with nature as our strongest ally.”

The first part of the argument is valid. The second premise in regard to population and "arming ourselves with nature" is the major problem of warfare biolabs and GMOs. Hurtling towards a population of 10 billion people is crazy. Trimming population the natural way is one of our solutions.

Music, maestro.

GL.

- By Gus Leonisky at 26 Mar 2020 - 8:41am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

the view from the professor...

AAAS Member Sabra Klein is angry at the missed opportunities that have brought the world to this moment—when everything has been crippled by the novel coronavirus. “We should have stayed the course and developed a vaccine,” she says, her voice trailing off. “We didn’t. We shelved it.”

She believes scientists could have done more when severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) appeared in China in 2002 or been more responsive on the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) that was first reported in Saudi Arabia in 2012 and later spread to the United States. If the scientific community had used the 2002 and 2012 coronaviruses as a test to develop a vaccine, we might not be where we are today.

Klein, a professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (JHBSPH), researches the differences between the male and female immune systems divorced from what she calls the ‘human condition’ or gender differences around the world that result in women not having equal access to health care and treatment. Her research in sex differences and infectious disease has implications for both men and women. For example, the interplay of a person’s hormones and how it affects the influenza virus (known as the flu), and more recently, why it appears men are more susceptible to Covid-19 infections than women.

Klein became an infectious disease expert later in her academic life, transitioning from her background in neuroscience to microbiology and immunology. “I enjoyed neuroscience, but I found myself much more interested in the connections to the immune systems,” she says. “For my post-doctoral training, I wanted to start to work in infectious diseases so that is when I began this transition.”

Today, her research concerns infectious disease from Covid-19, to Zika infections, to HIV. Key findings in her studies indicate that females typically mount more robust immune responses than males, no matter the virus.

“If you take immune cells from HIV positive men and if you take cells from HIV positive women and you put them on a plate and you expose them to an HIV antigen,” she says, “immune cells from women are going to be much more reactive, they are going to generate a much more robust and viral response.”

Still, over a decade ago, Klein was derogatorily referred to as an ‘Immuno-Feminist,’ by alpha males in the blogsphere. She was accused of applying feminist ideas to biology by people who had disagreed with her findings that showed women had a more robust immune system than men. One of the things that surprised her most during her research, and her critics too, was that the X chromosome in women was encoded with so many genes that controlled immune functions. There were also biological differences between males and females that helped in the functioning of immune systems through a process called hormone signaling.

Estrogen, the hormone found in women, Klein argues, is responsible for altering the signaling inside of an immune cell. The hormone coaxes the cell to either start or halt making protein in an inflammatory response or when repairing body tissue.

“The benefit of women sometimes having an overactive immune response is that when it comes to things like an infection, we often fight it better,” she says.

“We know that the mortality rate in China (for Covid-19) is significantly greater for men than for women,” she says. “We really don’t know why nobody is studying how the virus replicates or the immunity that is induced but we know that more men are ending up in intensive care units.”

A growing number of papers coming out of China are now disaggregating and comparing data between men and women, a development that Klein has taken note of. “It has been very refreshing so far and it tells me that people are starting to believe that this is something that requires consideration.”

Klein is trying to get ahead of the curve by raising money to study the differences between the older men and women in Baltimore and how they will respond to the virus. “When the vaccine is available, we can study the vaccine induced immunity and compare it between men and women,” she says.

Klein thinks that the Covid-19 virus could have been avoided if there had been more surveillance of animal populations. “We have known for so long that so many emerging viruses come from bats.” But, she concedes that it is costly to monitor animals for emerging threats, pointing out that many governments do not have the appetite to keep spending money on things that do not have an immediate benefit for the people.

“You do not find anything and then you have to keep justifying spending money for which year after year you find nothing,” she notes of the difficulties.

The novel coronavirus that is currently responsible for thousands of deaths is very closely related to the one that was sequenced from bats in the mid 2000’s. Klein suggests that to halt future outbreaks, sufficient funds should be pumped into drug discoveries and vaccines now. There were some drugs that worked in the past; based on the same platform as the standard seasonal flu vaccine.

“They might not have worked great but there was some efficacy,” she says.

Klein calls out what she sees as a lack of concern for scientists that need to do their work, even during the coronavirus epidemic. She says she has had her work disrupted like so many other scientists by what she calls the “aggressive process” of shutting down operations including research facilities—something that she calls “historic for an institution like this.”

She is worried that scientists have been ordered not to start new research.

“It is stressful for all of us and you don’t know when we resume normal operations,” she says.

Link only available to AAAS members.

nature is not "fighting back". don't "destroy it" nonethless...

This is a rush transcript and may contain errors. It will be updated.

Marc Stiener: I’m Marc Steiner, great to have you all with us on this day. The COVID-19 pandemic has much of the world gripped in fear, entire countries are on lockdown. People are fearful, and rightfully so, of being in contact with each other. For us here, empty shelves in supermarkets, no cars on the highways, empty streets, give you that eerily post apocalyptic feel. Donald Trump labeling this as the Chinese virus and urging us to go back to normalcy, seems unattached to reality. It’s not the Chinese flu, it’s not the other, it’s us. More accurately, it’s our destruction of natural habitats and a climate crisis that is unleashing these viruses among us.

COVID-19 was being blamed on the poor, peaceful pangolin. But this poor anteater that looks like an Armadillo, may be part of the reason the virus spread in China, but it’s our industrial development that’s destroying his habitat that brought them into contact with us. And then some thought it would be a good idea to eat these things. It’s not bats or pangolins, but what our human expansion has done to unleash viruses from Ebola to COVID-19. From the destruction of wild habitats to melting off permafrost and arctic shelves, viruses we’ve never known existed may be coming our way.

And we’re joined by Dr. Sonia Shah. She wrote the book Pandemic: Tracking Contagious from Cholera to Ebola and Beyond. Her newest book is The Next Great Migration: The Beauty and Terror of Life on the Move, that comes out in June. And her latest article published in the nation is Think Exotic Animals Are to Blame for the Corona Virus? Think again. And it’s being wildly read. So welcome Sonia Shah, good to have you with us.

Sonia Shah: Nice to be here.

Marc Stiener: Help us think again, so the connection between habitat loss and climate crisis can get lost in this conversation. And when we try to figure out how to avoid these things now and in the future, talk a bit about that connection.

Sonia Shah: This latest coronavirus is just the last in a series. Well, it won’t be the last, but it’s just the latest in a series of newly emerged pathogens. So over the past like 50, 60 years or so, we’ve had over 300 of these pathogens kind of newly emerge, or re-emerge into places where they’d never been seen before. So, that includes Ebola in West Africa in 2014, it had never been seen in that part of the continent before. It includes Zika in the Americas were it had never been seen before. We have new kinds of tick borne illnesses, new kinds of mosquito borne illnesses, new kinds of antibiotic resistant bacterial pathogens. And the list goes on and on, including of course this latest coronavirus. And about 60% of these new pathogens come from the same place. And that is the bodies of animals. About 70% of them come from the bodies of wild animals.

So, what I tried to do in my work is look at how does a microbe that is generally harmless in its native habitat, in its natural habitat, turn into a pandemic causing pathogens. What are the changes that have to happen for that process to occur? And what I found is that in a lot of cases it’s because humans are invading wildlife habitat. So when we cut down the trees where bats roost… If bats are roosting in some far off jungle, we cut down those trees, well they don’t just go away. They come and fly into our gardens, and backyards, and farms instead. So in all these ways when we destroy wildlife habitat, we force wildlife to come into closer contact to where we live, into little fragments of habitat that we have left for them and that eases all kinds of new kinds of contact between animals and humans.

It increases hunting, trading, uneven casual contact. For example, if you touched a piece of fruit that had some bat saliva on it you could get Ebola virus on your hands, and you put that your hand in your mouth and that’s it. The microbe that lives in the animals bodies has come into the human body, and that’s how the Ebola outbreak of 2014 actually started. And we will probably eventually be able to trace back this current pandemic to some kind of single quote unquote spill over event like that. But the root of it is microbes in animals coming into human bodies because we’re destroying their habitat and bringing them closer into contact with ours.

Marc Stiener: A couple of things here I’ve got to explore. What you mentioned a moment ago, I mean we’re talking about viruses, everything from Ebola to HIV, to Lyme disease in this country are all kind of erupting for the similar reason. And when you look at some of the new science coming out about the potential viruses being unleashed by the melting of permafrost in the Arctic ice shelves. When you add that to the habitat issue we, unfortunately and frighteningly, could just be seeing the beginning of what could erupt over the next decades. Do think that’s alarmist? Do you think that’s real?

Sonia Shah: I don’t know that the melting permafrost is sort of the biggest driver of this, I think invading wildlife habit is a bigger driver because you also have to think about which microbes in animals bodies can easily adapt to human bodies. And so that’s usually microbes that live in other mammals, and it’s usually ones that are more similar to us. So, we get a lot of pathogens from pigs for example, we’ll get fewer from reptiles, right? So, the source matters because each microbe has to kind of adapt. So this is a long process, this doesn’t happen instantly. What happens is there’s repeated contact between humans and the animal reservoir of these microbes. And those repeated contacts allow the microbe to slowly adapt to the human body, right? Because in the beginning it’s an animal microbe, it’s not going to make you sick necessarily, or your immune system’s going to get rid of it.

The pathogen has to adapt. So there has to be repeated contact over time. So we’ve seen these wet markets have existed, for example, which is a source of the SARS pathogen that came out in 2002, 2003, and may be the origins of the current Corona virus. Those wet markets existed for many, many years, but what happened over the past 20 or 30 years is they started to get bigger and bigger because the Chinese economy expanded and people were going farther and farther into wildlife habitat to invade, in places that are farther and farther away, bring animals from lots of different places closer together. So it’s that slow process of expansion and the repeated contact between humans and wildlife that allows these microbes to adapt and become human pathogens.

Marc Stiener: And a broader question here, if human expansion and capitalist development and all kinds of industrial development and development period are part of the causes that underlies these growth of viruses, then how do we think about what to do about that? I mean it’s one thing to talk about how you fight COVID-19 at this moment, and I think that’s one issue. The other issue is how do you prevent the COVID-19s of the future from erupting given the nature of human beings to expand? I mean you wrote in your article that even when you think of the neolithic period that was unleashed there, tuberculosis and measles that are still with us. So, how do we begin to talk as a society, as human beings, as a culture, how to change what we do in order not to have these explosions or is that even possible?

Sonia Shah: It is possible. We’re always going to have infectious diseases, right? I mean we live on a microbial planet and that’s sort of part of the human condition. So we don’t want to sanitize the planet of microbes or anything like that. So the trick is, do you have to have pandemics though? And I think from my research and reporting, the answer is absolutely not. Pandemics are manufactured by human activities. We’ll have infectious disease outbreaks, but we don’t have to have these massive pandemics that travel across the globe and result in what we’re seeing today. And one step towards that is, of course, reducing our destruction of wildlife habitat so that microbes that live in animals bodies stay in their bodies. Reducing the impact of climate change will help too because, of course, we know that a lot of species are moving into new places to escape the effects of the climate crisis. And as they do that, they’re moving into new kinds of contact with human populations also. So that provides other opportunities for these spillovers to happen.

But we also can sort of actively surveil where these spillovers are happening and kind of contain them at their source. We don’t know which microbe will cause the next pandemic, but we do know what the drivers are. We know that it’s things like invasion of wildlife habitat, lots of flight connections, lots of slums, lots of factory farms. These are all drivers of pandemic causing pathogens. So since we know that we can Predict where it’s most likely to happen. So scientists have actually come up with these global hotspot maps. There are places… It’s a map and it just shows where are all the places in the world where it’s most likely that a pandemic causing pathogen could emerge. And in those places we can do active surveillance, really look at all the microbes there. Don’t wait for the outbreak to happen, don’t wait for cases to emerge so people are already getting sick and the microbe’s already spreading exponentially. But actually look for them sort of preventively, to do that kind of active surveillance. And that was actually a project that was going on for about 10 years until the Trump administration killed it last year.

Marc Stiener: You’re talking about Predict and the stuff that CDC was doing that the budget was canceled, that’s what you’re talking about.

Sonia Shah: That’s right.

Marc Stiener: Talk a bit about that.

Sonia Shah: So that was a program funded by USAID and it involved lots of different agencies and academic institutions around the world. And what they would do is they would go to these disease hotspots and try to actively surveil how microbes might be changing. So they would sample say, scat from animals or take blood from farmers or hunters. They had a variety of different ways to actually actively look for these microbes and then see how they might be changing. And they actually were able to find about 900, I think, over the course of that 10 year period. And so then you can say, “Okay, well this microbe looks like it’s evolving to adapt to the human body in a way that could make it into a dangerous pathogen. Let’s change our behaviors on this local level so that it doesn’t have those opportunities anymore.” Maybe it’s changing hunting practices, or some trading practices, or something much more localized that you could alter through a small intervention as opposed to waiting until it starts erupting in epidemics and spreads around the world. And then thinking, “Oh, okay, now let’s try to contain it.”

Marc Stiener: So without being accusatory here, just larger questions in close. If Predict had been funded fully, if we had full funding to be able to look ahead and see what potential pathogens may arise, could this have been avoided? Is that possible or is that too much conjecture?

Sonia Shah: I mean it’s possible. This is all probabilities, right? So say there’s thousands of microbes out there that could become the next pandemic causing pathogen. If we could surveil and contain 80% of those, would our risk of pandemics go down? Yes, it would. Does it mean that this particular virus would not have emerged? Well, who knows?

Marc Stiener: And as we conclude Sonia give us a little tip for the future about what we should be wrestling with as a society in terms of how to go forward.

Sonia Shah: The first thing is we got to get this thing under control and what’s happening now is commercial pressures and political pressures are altering our containment strategy, and what we’re going to see is a bloodbath in our hospitals. So all of us need to chip in. And I think one of the things that’s really striking about these outbreaks of novel kinds of diseases is that there is no drug, there is no vaccine, there is no easy biomedical product that we can all use to solve it, right? Because they come up too fast and by the time you get the vaccine or the drug you’ve already had this whole wave of epidemic. So what that means is that the only thing that really works is collective action and solidarity. And I think we’re starting to see that in different parts of the world, and people are trying, and that’s really going to be the solution out of this thing.

Marc Stiener: Well Sonia Shah thank you for the work you do and the writing you do. It’s really important and I look forward to seeing what else you produce, look forward to your book coming out in June. And I want to thank you so much for joining us here on the real news today. I appreciate you taking the time with us, I know you’re very busy at this moment, so thank you so much.

Sonia Shah: Thank you.

Marc Stiener: And I’m Mark Steiner here for the Real News Network, thank you all for joining us. Let us know what you think. We’ll be covering this pandemic intensely from all different quarters. So take care and take care of yourself.

Read more:

https://therealnews.com/stories/coronavirus-ebola-sars-virus-outbreaks-h...

Read from top.