Search

Recent comments

- charlie's view....

2 hours 47 min ago - surprise?...

5 hours 33 min ago - anthropo-morphizing....

8 hours 17 min ago - extortion and bribery....

11 hours 17 min ago - war tools....

15 hours 16 min ago - of fleas....

18 hours 48 min ago - 12 feet under....

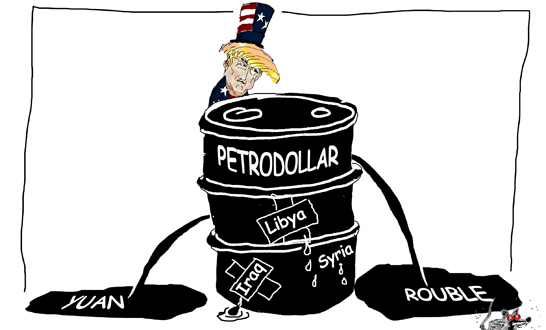

19 hours 4 min ago - killing the dollar...

19 hours 11 min ago - needs the cash....

1 day 3 hours ago - fall guy...

1 day 3 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

the bottom of the barrel...

For his part, Senator Chris Murphy bemoaned the fact that US President Donald Trump is not interested in "projecting liberal values" into other countries, let alone trade liberalization. The White House's recent initiative to introduce additional tariffs on aluminum and steel imports has prompted a wave of criticism from the US' global partners and allies.

Furthermore, the US president made it clear that the US will not support numerous international institutions and withdrew from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

Murphy called upon the defenders of the liberal world order to team up and "build new alliances within their societies."

On the other hand, the transatlantic bloc has seemingly recognized its failure to impose a Western-style political order on Russia and China.

"We can no longer expect that the principles of liberal democracy will expand across the globe," Rogin wrote. "We can no longer assume the United States will carry the bulk of the burden."

Kosyrev suggested that the center of trans-Atlantic globalism will most likely move to either Brussels or Canada or even Australia.

Following Trump's win in 2016, The New York Times called Germany's Angela Merkel the last defender of the trans-Atlantic alliance and liberal values.

However, not everything is rosy in the European garden, Kosyrev noted referring to the rise of right-wing forces in Austria, Italy, Hungary, Poland and other EU member states. Although Merkel still remains at the helm of German politics, the right-wing Alternative for Germany (AfD) entered the Bundestag in September 2017 as the third-largest party.

Given all of the above, the rebuilding of the liberal international order will take years, Kosyrev presumed.

Read more:

https://sputniknews.com/analysis/201803241062845827-russia-china-multipo...

- By Gus Leonisky at 25 Mar 2018 - 10:24am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

trash your own...

China has long been the world's largest importer of waste and recyclable commodities. Now that Trump has threatened harsh new tarrifs in an escalating trade war, Beijing has announced that it will not overturn a new ban on accepting shipments of garbage from the US and other countries, leaving industrialized nations scrambling for options on how to dispose of an ever-mounting landscape of trash.

As China in 2016 was responsible for accepting some 80 percent of US recyclable waste, the move has business and legislators pleading with Beijing to roll back new restrictions on waste imports.

A Washington representative told a World Trade Organization (WTO) meeting on Friday that China's ban on scrap imports was "disruptive' and hinted that Beijing would be to blame for rapidly escalating landfill in the US and the rest of the world.

"China's import restrictions on recycled commodities have caused a fundamental disruption in global supply chains for scrap materials, directing them away from productive reuse and toward disposal," suggested the US spokesperson at the WTO Council for Trade in Goods meeting in Geneva.

US trade representatives at the WTO in Switzerland accused Beijing of altering China's import recycling rules too fast, resulting in a compromised industry that is not able to evolve and could face collapse.

Read more:

https://sputniknews.com/world/201803241062870960-china-stops-import-worl...

on wahhabi proselytism...

In an interview with the Washington Post, Crown Prince Mohamed bin Salman said that Saudi Arabia had begun spreading Wahhabi ideology at the urging of its Western allies, during the Cold War, to counter the USSR.

A statement by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (nicknamed "MBS") published by the Washington Post on March 22nd, apparently unnoticed in the French-language media, serves as an admission. Indeed, the Saudi Crown Prince assured that the Wahhabi ideology was propagated during the second half of the twentieth century by Riyadh at the request of the western allies of the kingdom, in order to counter the influence of the Soviet Union in Muslim countries.

Translation by Jules Letambour

Read more:

https://francais.rt.com/international/49248-nous-avons-propage-wahhabism...

If you read the Washington Post today, you should recognise that the USA is a bloody big mess... Let's say it has been crap for a very long time, since its civil war in fact, but has hidden the shit well with its focus on "the dollar". It has thus exported shit in parity with the dollar ever since.

As well, if you have forgotten or do not know, 98 per cent of terror attacks in the world comes from the Wahhabi Sunnis... (ie Saudi Arabia).

See also:

http://www.yourdemocracy.net.au/drupal/node/28653

THE SINGLE MOST important issue...

THE SINGLE MOST important issue in allocating national resources is war versus peace, or as macroeconomists put it, “guns versus butter.” The United States is getting this choice profoundly wrong, squandering vast sums and undermining national security. In economic and geopolitical terms, America suffers from what Yale historian Paul Kennedy calls “imperial overreach.” If our next president remains trapped in expensive Middle East wars, the budgetary costs alone could derail any hopes for solving our vast domestic problems.

It may seem tendentious to call America an empire, but the term fits certain realities of US power and how it’s used. An empire is a group of territories under a single power. Nineteenth-century Britain was obviously an empire when it ruled India, Egypt, and dozens of other colonies in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean. The United States directly rules only a handful of conquered islands (Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Guam, Samoa, the Northern Mariana Islands), but it stations troops and has used force to influence who governs in dozens of other sovereign countries. That grip on power beyond America’s own shores is now weakening.

The scale of US military operations is remarkable. The US Department of Defense has (as of a 2010 inventory) 4,999 military facilities, of which 4,249 are in the United States; 88 are in overseas US territories; and 662 are in 36 foreign countries and foreign territories, in all regions of the world. Not counted in this list are the secret facilities of the US intelligence agencies. The cost of running these military operations and the wars they support is extraordinary, around $900 billion per year, or 5 percent of US national income, when one adds the budgets of the Pentagon, the intelligence agencies, homeland security, nuclear weapons programs in the Department of Energy, and veterans benefits.

The $900 billion in annual spending is roughly one-quarter of all federal government outlays.

It may seem tendentious to call America an empire, but the term fits certain realities of US power and how it’s used. An empire is a group of territories under a single power.

Nineteenth-century Britain was obviously an empire when it ruled India, Egypt, and dozens of other colonies in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean. The United States directly rules only a handful of conquered islands (Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Guam, Samoa, the Northern Mariana Islands), but it stations troops and has used force to influence who governs in dozens of other sovereign countries. That grip on power beyond America’s own shores is now weakening.

The scale of US military operations is remarkable. The US Department of Defense has (as of a 2010 inventory) 4,999 military facilities, of which 4,249 are in the United States; 88 are in overseas US territories; and 662 are in 36 foreign countries and foreign territories, in all regions of the world. Not counted in this list are the secret facilities of the US intelligence agencies. The cost of running these military operations and the wars they support is extraordinary, around $900 billion per year, or 5 percent of US national income, when one adds the budgets of the Pentagon, the intelligence agencies, homeland security, nuclear weapons programs in the Department of Energy, and veterans benefits. The $900 billion in annual spending is roughly one-quarter of all federal government outlays.

The United States has a long history of using covert and overt means to overthrow governments deemed to be unfriendly to US interests, following the classic imperial strategy of rule through locally imposed friendly regimes. In a powerful study of Latin America between 1898 and 1994, for example, historian John Coatsworth counts 41 cases of “successful” US-led regime change, for an average rate of one government overthrow by the United States every 28 months for a century. And note: Coatsworth’s count does not include the failed attempts, such as the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba.

This tradition of US-led regime change has been part and parcel of US foreign policy in other parts of the world, including Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. Wars of regime change are costly to the United States, and often devastating to the countries involved. Two major studies have measured the costs of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. One, by my Columbia colleague Joseph Stiglitz and Harvard scholar Linda Bilmes, arrived at the cost of $3 trillion as of 2008. A more recent study, by the Cost of War Project at Brown University, puts the price tag at $4.7 trillion through 2016. Over a 15-year period, the $4.7 trillion amounts to roughly $300 billion per year, and is more than the combined total outlays from 2001 to 2016 for the federal departments of education, energy, labor, interior, and transportation, and the National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health, and the Environmental Protection Agency.

It is nearly a truism that US wars of regime change have rarely served America’s security needs. Even when the wars succeed in overthrowing a government, as in the case of the Taliban in Afghanistan, Saddam Hussein in Iraq, and Moammar Khadafy in Libya, the result is rarely a stable government, and is more often a civil war. A “successful” regime change often lights a long fuse leading to a future explosion, such as the 1953 overthrow of Iran’s democratically elected government and installation of the autocratic Shah of Iran, which was followed by the Iranian Revolution of 1979. In many other cases, such as the US attempts (with Saudi Arabia and Turkey) to overthrow Syria’s Bashar al-Assad, the result is a bloodbath and military standoff rather than an overthrow of the government.

. . .

WHAT IS THE DEEP motivation for these profligate wars and for the far-flung military bases that support them?

From 1950 to 1990, the superficial answer would have been the Cold War. Yet America’s imperial behavior overseas predates the Cold War by half a century (back to the Spanish-American War, in 1898) and has outlasted it by another quarter century. America’s overseas imperial adventures began after the Civil War and the final conquests of the Native American nations. At that point, US political and business leaders sought to join the European empires — especially Britain, France, Russia, and the newly emergent Germany — in overseas conquests. In short order, America grabbed the Philippines, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Panama, and Hawaii, and joined the European imperial powers in knocking on the doors of China.

As of the 1890s, the United States was by far the world’s largest economy, but until World War II, it took a back seat to the British Empire in global naval power, imperial reach, and geopolitical dominance. The British were the unrivaled masters of regime change — for example, in carving up the corpse of the Ottoman Empire after World War I. Yet the exhaustion from two world wars and the Great Depression ended the British and French empires after World War II and thrust the United States and Russia into the forefront as the two main global empires. The Cold War had begun.

The economic underpinning of America’s global reach was unprecedented. As of 1950, US output constituted a remarkable 27 percent of global output, with the Soviet Union roughly a third of that, around 10 percent. The Cold War fed two fundamental ideas that would shape American foreign policy till now. The first was that the United States was in a struggle for survival against the Soviet empire. The second was that every country, no matter how remote, was a battlefield in that global war. While the United States and the Soviet Union would avoid a direct confrontation, they flexed their muscles in hot wars around the world that served as proxies for the superpower competition.

Over the course of nearly a half century, Cuba, Congo, Ghana, Indonesia, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Iran, Namibia, Mozambique, Chile, Afghanistan, Lebanon, and even tiny Granada, among many others, were interpreted by US strategists as battlegrounds with the Soviet empire. Often, far more prosaic interests were involved. Private companies like United Fruit International and ITT convinced friends in high places (most famously the Dulles brothers, Secretary of State John Foster and CIA director Allen) that land reforms or threatened expropriations of corporate assets were dire threats to US interests, and therefore in need of US-led regime change. Oil interests in the Middle East were another repeated cause of war, as had been the case for the British Empire from the 1920s.

These wars destabilized and impoverished the countries involved rather than settling the politics in America’s favor. The wars of regime change were, with few exceptions, a litany of foreign policy failure. They were also extraordinarily costly for the United States itself. The Vietnam War was of course the greatest of the debacles, so expensive, so bloody, and so controversial that it crowded out Lyndon Johnson’s other, far more important and promising war, the War on Poverty, in the United States.

The end of the Cold War, in 1991, should have been the occasion for a fundamental reorientation of US guns-versus-butter policies. The occasion offered the United States and the world a “peace dividend,” the opportunity to reorient the world and US economy from war footing to sustainable development. Indeed, the Rio Earth Summit, in 1992, established sustainable development as the centerpiece of global cooperation, or so it seemed.

The far smarter approach will be to maintain America’s defensive capabilities but end its imperial pretensions.

Alas, the blinders and arrogance of American imperial thinking prevented the United States from settling down to a new era of peace. As the Cold War was ending, the United States was beginning a new era of wars, this time in the Middle East. The United States would sweep away the Soviet-backed regimes in the Middle East and establish unrivalled US political dominance. Or at least that was the plan.

. . .

THE QUARTER CENTURY since 1991 has therefore been marked by a perpetual US war in the Middle East, one that has destabilized the region, massively diverted resources away from civilian needs toward the military, and helped to create mass budget deficits and the buildup of public debt. The imperial thinking has led to wars of regime change in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Yemen, Somalia, and Syria, across four presidencies: George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama. The same thinking has induced the United States to expand NATO to Russia’s borders, despite the fact that NATO’s supposed purpose was to defend against an adversary — the Soviet Union — that no longer exists. Former Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev has emphasized that eastward NATO expansion “was certainly a violation of the spirit of those declarations and assurances that we were given in 1990,” regarding the future of East-West security.

There is a major economic difference, however, between now and 1991, much less 1950. At the start of the Cold War, in 1950, the United States produced around 27 percent of world output. As of 1991, when the Dick Cheney and Paul Wolfowitz dreams of US dominance were taking shape, the United States accounted for around 22 percent of world production. By now, according to IMF estimates, the US share is 16 percent, while China has surpassed the United States, at around 18 percent. By 2021, according to projections by the International Monetary Fund, the United States will produce roughly 15 percent of global output compared with China’s 20 percent. The United States is incurring massive public debt and cutting back on urgent public investments at home in order to sustain a dysfunctional, militarized, and costly foreign policy.

Thus comes a fundamental choice. The United States can vainly continue the neoconservative project of unipolar dominance, even as the recent failures in the Middle East and America’s declining economic preeminence guarantee the ultimate failure of this imperial vision. If, as some neoconservatives support, the United States now engages in an arms race with China, we are bound to come up short in a decade or two, if not sooner. The costly wars in the Middle East — even if continued much less enlarged in a Hillary Clinton presidency — could easily end any realistic hopes for a new era of scaled-up federal investments in education, workforce training, infrastructure, science and technology, and the environment.

The far smarter approach will be to maintain America’s defensive capabilities but end its imperial pretensions. This, in practice, means cutting back on the far-flung network of military bases, ending wars of regime change, avoiding a new arms race (especially in next-generation nuclear weapons), and engaging China, India, Russia, and other regional powers in stepped-up diplomacy through the United Nations, especially through shared actions on the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, including climate change, disease control, and global education.

Many American conservatives will sneer at the very thought that the United States’ room for maneuver should be limited in the slightest by the UN. But think how much better off the United States would be today had it heeded the UN Security Council’s wise opposition to the wars of regime change in Iraq, Libya, and Syria. Many conservatives will point to Vladimir Putin’s actions in Crimea as proof that diplomacy with Russia is useless, without recognizing that it was NATO’s expansion to the Baltics and its 2008 invitation to Ukraine to join NATO, that was a primary trigger of Putin’s response.

In the end, the Soviet Union bankrupted itself through costly foreign adventures such as the 1979 invasion of Afghanistan and its vast over-investment in the military. Today the United States has similarly over-invested in the military, and could follow a similar path to decline if it continues the wars in the Middle East and invites an arms race with China. It’s time to abandon the reveries, burdens, and self-deceptions of empire and to invest in sustainable development at home and in partnership with the rest of the world.

Jeffrey D. Sachs is University Professor and Director of the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University, and author of “The Age of Sustainable Development.”

Published OCTOBER 30, 2016:

https://www.bostonglobe.com/opinion/2016/10/30/the-fatal-expense-american-imperialism/teXS2xwA1UJbYd10WJBHHM/story.html

Read from top.

decision point-ish...

This indecisiveness has prompted Trump to warm up further with Saudi Arabia, the same country that helped finance and logistically support the rise of jihadist Salafists, including Al-Qaida and Islamic State (IS, formerly ISIS). Now, Trump wants the Saudi kingdom to financially underwrite US efforts to consolidate the Sunnis in Syria and Iraq against what both Trump and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman regard as a threat from Iran spreading its influence throughout the region.

It also can be seen as a desperate move by the Trump administration to maintain some modicum of influence in the Middle East in the face of its role rapidly being replaced by the influence of Russia, Iran and now Turkey.

Russia and Iran were invited by the government of Syrian President Bashar Assad to assist in fighting jihadist Salafist fighters, many being foreign fighters, along with Al-Qaida and Islamic State. However, US troops never were invited by the Syrian government and have been labeled as an occupying force. In addition, the US Congress never authorized such a move.

Read more:

https://www.rt.com/op-ed/423395-us-troops-withdrawal-syria/

nepotism, corruption, ineptitude, and lawlessness...

To borrow from the British definition of an ambassador, United States military leaders are honest soldiers promoted in rank to champion war with reckless disregard for the truth. This practice persists despite the catastrophic waste of lives and money because the untruths are never punished. Congress needs to correct this problem forthwith.

General Joseph F. Dunford, Jr., chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, exemplifies the phenomenon. As reported in The Washington Post, Dunford recently voiced optimism about defeating the Afghan Taliban in the seventeenth year of a trillion-dollar war that has multiplied safe havens for international terrorists, the opposite of the war’s original mission. While not under oath, Dunford insisted, “This is not another year of the same thing we’ve been doing for 17 years. This is a fundamentally different approach…[T]he right people at the right level with the right training [are in place]…”

There, the general recklessly disregarded the truth. He followed the instruction of General William Westmoreland who stated at the National Press Club on November 21, 1967 that the Vietnam War had come to a point “where the end begins to come into view.” The 1968 Tet Offensive was then around the corner, which would provoke Westmoreland to ask for 200,000 more American troops. The Pentagon Papers and Lieutenant General H.R. McMaster’s Dereliction of Dutyhave meticulously documented the military’s reckless disregard for the truth throughout the Vietnam War.

Any fool can understand that continuing our 17-year-old war in Afghanistan is a fool’s errand. The nation is artificial. Among other things, its disputed border with Pakistan, the Durand Line, was drawn in 1896 between the British Raj and Afghan Amir Abdur Rahmen Khair. Afghanistan’s population splinters along tribal, ethnic, and sectarian lines, including Pushtans, Uzbeks, Hazara, Tajiks, Turkmen, and Balochi. Its government is riddled with nepotism, corruption, ineptitude, and lawlessness. Election fraud and political sclerosis are endemic. Opium production and trafficking replenish the Taliban’s coffers.

Read more:

http://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/when-military-leaders-ha...

a caspian solution...

in 2017, the situation was thus described by an expert:

Back in the 1990s, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Caspian Sea was described as the next Alaska or North Sea for the oil and gas industry. But it could never be that, for the simple and obvious reason that the Caspian is landlocked. Moreover, its five littoral states – Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia and Turkmenistan – have yet to resolve their long-standing territorial disputes, which have prevented full exploitation of the Caspian Sea’s energy potential.

Read more:

https://www.gisreportsonline.com/caspian-oil-and-gas-in-a-world-of-plent...

From James O'Neill:

Caspian Sea Agreement Symptomatic of Wider Geopolitical Changes

On 12 August 2018 the five littoral states to the Caspian Sea (Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia and Turkmenistan) signed an historic agreement governing the use of the Caspian Sea. The negotiations had been ongoing for more than 20 years.

One of the issues was with the Caspian should be regarded as a sea (it is salty but completely enclosed) or a lake. If the former, then it would be governed by the international law of the sea. If defined as a lake, then the resources would be divided equally between the five States. In the event, the five nations agreed to accord it ‘a special status,’ neither lake nor sea. Whether this unique formulation will be recognised by non-littoral States is an open question.

There are several significant elements to the Caspian Sea Convention (CSC) that are worthy of note. The first aspect is the size of the resources at stake. The Caspian Sea basin is known to hold 50 billion barrels of oil in proven reserves, and nearly 9 trillion cubic metres of natural gas. To put that in perspective, the gas reserves are greater then the entire known United States reserves.

The agreement signed on 12 August gave each of the five states a 15 nautical mile exclusive territorial zone, plus a further 10 nautical mile exclusive fishing zone. The balance of the sea area was for common use. Its economic development would therefore be a joint exercise with the benefits equally shared. A Caspian Economic Forum was also established to determine, inter alia, the practical means and effects of such cooperation.

The second aspect of the agreement relates to security arrangements. All non-littoral States are forbidden to have foreign military bases. This is specifically directed at NATO, which continues its encroachment and attempted encroachment in all nations with proximity to Russia.

Russia is the underwriter of security in the Caspian, a factor that increases its geopolitical strength viz a viz other nations, and in particular Iran that is looking increasingly to secure arrangements unaffected by the unilateral sanctions imposed by the United States.

Both Russia and China are developing closer economic and political ties with Iran. Both countries have made significant investments in Iranian infrastructure and resource development. Iran is also a pivotal State in China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Neither Russia nor China are likely to tolerate overt aggression against Iran of the type advocated by some of the more extreme neocon elements of the US administration.

That does not preclude those same elements increasing the intensity of the hybrid warfare waged against Iran for many years, including overt support for the terrorist MEK group. Hybrid warfare is also the main means by which the US will seek to undermine China’s Belt and Road Initiative, as overt warfare is now, as the Rand Corporation acknowledged recently, “unthinkable.”

The leaders of Iran and Kazakhstan also held separate meetings, an object of which in part was to establish economic links bypassing the United States dollar. This also reflects a developing trend of a move away from the US dollar, the ramifications of which are potentially enormous.

The third major consequence is in the links between some members of the CSA and related Eurasian organisations. Iran had earlier this year signed a free trade agreement with the Eurasian Economic Union, (EAEU) two of whose members, Kazakhstan and Russia are also parties to the CSC. Iran is an observer State (and likely full member soon) of the Shanghai Corporation Organisation. That organization’s full members include CSC States Russia and Kazakhstan, as well as neighbouring Pakistan and fellow SCO observer State Afghanistan. A resolution of the long running Afghanistan war will require the co-operation of Afghanistan’s Central Asian neighbours, all of whom are members of the SCO.

The CSC therefore represents a further step in the significant shift of geopolitical power to the Eurasian heartland. Although China was not a party to the CSC it is nonetheless the dominant economic power in the region, with close ties to the CSC signatories, particularly through the SCO, but also with non-member States such as Turkmenistan from whom it is a major importer of natural gas.

Although there are important differences between the Caspian Sea and the South China Sea, there are also lessons that can be drawn. Following the recent ASEAN meeting in Singapore, the ASEAN nations and China announced that they had agreed upon a new draft code of conduct for the littoral States of the South China Sea. Those negotiations had also been very lengthy.

The draft code of conduct underscores the importance of those nations most affected by the issues in dispute being the ones best able to formulate a resolution when they are able to do so. Those negotiations arguably have a better chance of success, absent the involvement of outside countries such as the United States and Australia. The actions and statements of those two nations demonstrate an inability to promote a peaceful resolution of the South China Sea issues, preferring instead a provocative and confrontational methodology.

The Caspian Sea Convention and the South China Sea code of conduct provide evidence that an alternative model is available.

James O’Neill is a barrister at law and geopolitical analyst. He may be contacted at

joneill@qldbar.asn.au

Read from top.

Why the west will do everything to kill "that deal"...

Iranian President Hasan Rouhani gave his Caspian competitors fifty percent of what Teheran used to have during its partnership with the USSR. Many in Iran found this move strange. Why did the Iranian president give up and ensured Azerbaijan with control over disputed deposits in the Caspian Sea? Russia lost its right to veto the construction of pipelines along the bottom of the Caspian Sea. Does Turkmenistan benefit from all this? What did Kazakhstan lose in the deal?

On August 12, the leaders of Russia, Kazakhstan, Iran, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan signed the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea. They agreed that the water area would be divided according to the median principle, which Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Russia had previously used to delimit the border between themselves. Territorial waters and the state border will be designated by the 15-mile zone, plus ten miles - this is a fishing zone with exclusive rights. The rest will be referred to as the neutral/common water area.

...

As a member of the Eurasian Economic Union, Kazakhstan will receive a duty-free exit to the seas via the Russian transport system.

Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan have agreed to Russia's and Iran's military presence in the water area of the Caspian Sea. This is definitely a disadvantage, because Russia and Iran are known for their strong opposition to the expansion of the West. They are also considered rivals and even enemies of the West. Therefore, Russia's and Iran's neighbors may get into hot water in case of a military conflict.

See more at http://www.pravdareport.com/world/ussr/16-08-2018/141410-caspian_sea_div...

should you wonder why your country has been bombed...

https://www.corbettreport.com/federalreserve/

Read from top.