Search

Recent comments

- corrupt brussels....

47 min 19 sec ago - criminals....

1 hour 28 min ago - more deads....

8 hours 21 min ago - more warmish....

1 day 2 hours ago - invented sentence....

1 day 4 hours ago - trump's WMDs.....

1 day 6 hours ago - antics.....

1 day 6 hours ago - frenemies....

1 day 9 hours ago - BS king....

1 day 9 hours ago - routine murder....

1 day 11 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

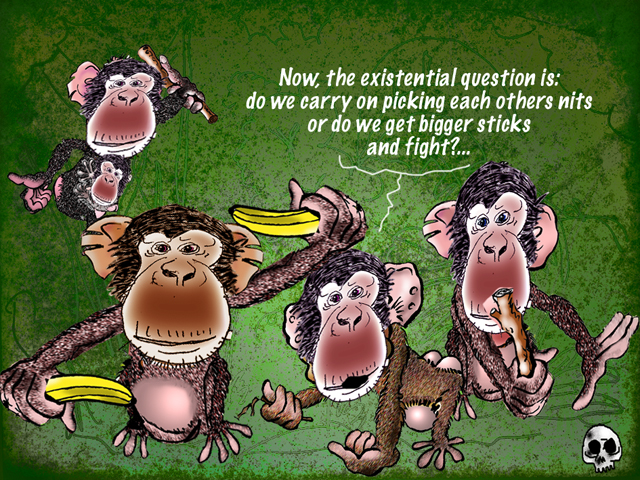

evolution of hominids: when the ancestors stopped nit-picking...

nits

nits

- By Gus Leonisky at 20 Dec 2017 - 9:37am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

slowly, adding missing links...

Archaeologists have unearthed 300,000-year-old fossilized bones of early humans — the oldest remains of Homo sapiens yet discovered, two new studies report. The ancient bones contain a mix of modern and primitive features that hint at an early, and previously unknown, phase of our species’s evolution.

read more:

https://www.theverge.com/2017/6/7/15759712/fossils-homo-sapiens-early-mo...

See also:

http://www.yourdemocracy.net.au/drupal/node/8011

"improving" the stick...

The US government has lifted a three-year ban on making lethal viruses in the lab, saying the potential benefits of disease preparedness outweigh the risks.

Labs will now be able to manufacture strains of influenza, Sars and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (Mers).

The ban was imposed following safety breaches at federal institutions involving anthrax and avian flu.

Now a scientific review panel will have to green-light each research proposal.

It will only be allowed to go ahead if the panel determines there is no safer way to conduct the research and that the benefits it will provide justify the risk.

Critics say such "gain-of-function" research still risks creating an accidental pandemic.

But supporters of removing the ban say many US states are poorly prepared for an almost-inevitable outbreak of a deadly virus.

"I believe nature is the ultimate bioterrorist and we need to do all we can to stay one step ahead," said Samuel Stanley, chairman of the National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity, which provided guidance on the new policy.

"Basic research on these agents by laboratories that have shown they can do this work safely is key to global security."

read more:

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-42426548

Time to put the "bottle stopper" on biological weapons — and other nasty sticks for that matter.... Read from top...

2017, when satire could not outdo the ridiculous reality...

Some of the year’s stories have been difficult, if not impossible, for satire to process. As any other year, 2017 has been scarred by its share of domestic and international tragedy. If the underlying issues circulating beneath such matters are to be addressed in a comedic context, it requires utmost delicacy, sensitivity and care, clubs which are not always in the satirical golf bag.

January began with the final 19 days of human history in which Donald Trump Had Never Been President Of The USA. On the 20th, that all changed irrevocably. At what was, despite the snarks of the online naysayers and fact-wielders, the best-attended American Presidential Inauguration for almost four years, Mr Trump was simultaneously sworn in and sworn at.

The reaction to his inauguration was swift, global and striking. Roger Federer, tennis’s resident Michelangelo, was inspired to bring some beauty back into a world scarred from the top by resentment, anger and paranoia, and promptly won the Australian Open, his first major title for almost five years.

Also in January, the remote Marshall Islands in the Pacific suffered a full internet blackout, and instantly rocketed to the top of the World’s Happiest Nations chart.

In April, Theresa May, the acting prime minister, called an unlosable general election. In May, she campaigned with the ferocity of a blancmange, exuding the strength and stability of an underboiled egg on a tightrope. In June, she lost, managing to cling to power only by virtue of losing it less badly than everyone else, and a coalition deal that put the “oh, my” into “compromise”. Jeremy Corbyn, widely touted as unelectable, triumphantly also lost, but by much less than people had expected, the ideal result for any politician.

May’s Brexitically dominated year reached its zenith in October, when a photograph of her sitting alone at a table during talks in Brussels won her a gold award for Best One-Woman Metaphor For Britain’s European Future from the International Foundation For Symbolic Pictures.

Read more:

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2017/dec/29/satire-busy-year-ho...

of "western" values and flag waving...

European settlers in Australia are indeed heirs to a particular tradition (or related traditions). But that European heritage cannot simply be reduced to a core set of "Western values." For much of its history, Europe was focused on virtues rather than values, and was characterised by an openness to past cultures that were essentially non-European.

Given the revolutionary potential of this outward and backward-looking perspective, it is curious that the invocation of a classical and Christian heritage is these days is regarded as hallmark of moral and political conservatism.

When we look closely at the relevant history, this identification seems incongruous. Harvard Classicist Bernard Knox gets it exactly right when he tells us how strange it is to find classical Greeks "assailed as emblems of reactionary conservatism, of enforced conformity." In fact, as he points out, "their role in the history of the West has always been innovative, sometimes indeed subversive, even revolutionary." Something similar can be said of central elements of the Christian tradition which have provided the motivation for radical social and political reforms.

I fully endorse the sentiment that we need a greater familiarity with our own cultural, religious and intellectual past. But the study of what we might call "the Western tradition" will not turn out to be as comforting to advocates of conservative moral and political values as they might imagine. We will see that there is no neat alignment of the study of tradition with traditionalism and political conservatism. Rather the relevant history will bear witness to an ongoing conversation and a continuous dialogue with other cultural traditions. That dialogue was as robust in the middle ages and early modern period as in the post-Enlightenment era.

It is here that the great potential of a "Western tradition" project lies - not in the fetishizing of some imagined canon of fixed values, but in the preservation of a rich and varied past that can continue to serve as on ongoing challenge to the priorities and "values" of the present.

And it follows that it is not just long-gone cultures that can play this role, but also those that we encounter in the contemporary world. Knowledge of our own cultural traditions can be deeply enriched by perspectives gained from knowledge of other cultures. As the great comparative linguist and religionist Max Mueller succinctly put it (in the idiom of his time), "he who knows one, knows none."

Peter Harrison is an Australian Laureate Fellow and Director of the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities, University of Queensland. This is an edited version of an IASH Public Lecture, first delivered on 30 August, 2017 at the University of Queensland.

Read more:

http://www.abc.net.au/religion/articles/2018/01/17/4790945.htm

Meanwhile:

Not only were British colonists at war with Australia's First People, but irrefutable evidence shows that – at least in Tasmania – they were trying to wipe them from the Earth. Dr Kristyn Harman reports.

AT A PUBLIC MEETING in Hobart in the late 1830s, Solicitor-General Alfred Stephen – later Chief Justice of New South Wales – shared with the assembled crowd his solution for dealing with “the Aboriginal problem”. If the colony could not protect its convict servants from Aboriginal attack “without extermination”, said Stephen, “then I say boldly and broadly exterminate!”

Voluminous written and archaeological records and oral histories provide irrefutable proof that colonial wars were fought on Australian soil between British colonists and Aboriginal people. More controversially, surviving evidence indicates the British enacted genocidal policies and practices — the intentional destruction of a people and their culture.

When lawyer Raphael Lemkin formulated the idea of “genocide” after the second world war, he included Tasmania as a case study in his history of the concept. Lemkin drew heavily on James Bonwick’s 1870 book, The Last of the Tasmanians, to engage with the island’s violent colonial past.

Curiously, books published before and since Bonwick’s have stuck to a master narrative crafted during and immediately after the Tasmanian conflict. This held that the implementation and subsequent failure of conciliatory policies were the ultimate cause of the destruction of the majority of Tasmanian Aboriginal people. The effect of this narrative was to play down the culpability of the government and senior colonists.

More recent works have challenged this narrative. In his 2014 book, The Last Man: A British Genocide in Tasmania, Professor Tom Lawson made a compelling case for the use of the word “genocide” in the context of Tasmania’s colonial war in the 1820s and early 1830s, when the island was still called Van Diemen’s Land. As Lawson writes, in the colony’s early decades, “extermination” and “extirpation” were words used by colonists when discussing the devastating consequences of the colonial invasion for the island’s Aboriginal inhabitants.

Read more:

https://independentaustralia.net/australia/australia-display/the-demons-...