Search

Recent comments

- albo is correct....

56 min 59 sec ago - robbery....

2 hours 33 min ago - speaking russian....

2 hours 41 min ago - watching....

2 hours 48 min ago - deceit....

4 hours 52 min ago - no rules.....

5 hours 42 min ago - young and old.....

6 hours 5 min ago - a role to play....

14 hours 25 min ago - hitlerite lies....

19 hours 2 min ago - ignoring....

21 hours 26 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

on the flu...

The flu outbreak of 1918 killed three times more people than died during WWI. Why is it so? The common flu is easy to catch. We get flu jabs (vaccination) but the flu virus is a shifty one. Evolution makes it very uncanny. Pneumonia, as a secondary stage of the flu can be deadly.

Meanwhile:

Gadfly has been swallowing handfuls of pills in an effort to shake off the vile flu. Among the various witches’ brews on the market is a tablet composed of olive leaf and echinacea. It’s meant to work but when I read the label it helpfully advised to take it before you get the flu.

Hilaire Belloc put it so masterfully:

“Physicians of the utmost fame

were called at once; but when they came

They answered, as they took their fees,

‘There is no cure for this disease’.”

https://www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/2017/08/26/gadfly-marriage-misguidan...

We wish the Gadfly (Richard Ackland) a speedy recovery. Actually, the point here is to avoid exertion, take a lot of rest in bed, avoiding contact with other humans and birds... while drinking a sip of rum in the morning and sleep, patiently.

Why was 1918 flu pandemic so deadly?

Research offers new clue

Published Tuesday 29 April 2014

By Catharine Paddock PhD

In 1918, as one global devastation in the shape of World War I came to an end, people around the world found themselves facing another deadly enemy, pandemic flu. The virus killed more than 50 million people, three times the number that fell in the Great War, and did this so much faster than any other illness in recorded history.

But why was that particular pandemic so deadly? Where did the virus come from and why was it so severe? These questions have dogged scientists ever since. Now, a new study led by the University of Arizona (UA) may have solved the mystery.

Michael Worobey, a professor in UA College of Science’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, and colleagues describe their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

They hope the study not only offers some new clues about the deadliness of the 1918 pandemic, but will also help improve strategies for vaccination and pandemic prevention, as Prof. Worobey explains:

“If our model is correct, then current medical interventions, especially antibiotics and vaccines, against several pneumonia-causing bacteria, could be expected to dramatically reduce mortality, if we were faced today with a similar set of pandemic ingredients.”

The 1918 pandemic killed predominantly young adults

One of the questions that has been particularly vexing is why the 1918 pandemic human influenza A virus killed so many young adults in the prime of life, he says, adding: “It has been a huge question whether there was something special about that situation, and whether we should expect the same thing to happen tomorrow.”

Researchers reconstructed the origins of the 1918 pandemic virus, the classic swine flu and the postpandemic seasonal H1N1flu virus lineage that circulated between 1918 and 1957, to find out why the 1918 pandemic was so deadly.

Usually, the human influenza A virus is deadlier to infants and the elderly. But the 1918 strain killed many people in their 20s and 30s, who mainly died from secondary bacterial infections, especially pneumonia.

For their investigation, the researchers developed an unprecedentedly accurate “molecular clock,” a technique that looks at the rate at which mutations build up in given stretches of DNA over time.

Evolutionary biologists use molecular clocks to reconstruct family trees, follow lineage splitting and find common ancestors of different strains of viruses and other organisms.

Prof. Worobey and his team used their molecular clock to reconstruct the origins of the 1918 pandemic virus, the classic swine flu and the postpandemic seasonal H1N1 flu virus lineage that circulated between 1918 and 1957.

Genetic material from bird flu virus picked up just before 1918

They found that a human H1 virus that had been circulating among humans since around 1900 picked up genetic material from a bird flu virus just before 1918 and this became the deadly pandemic strain.

Exposure to previous strains of flu virus does offer some protection to new strains. This is because the immune system reacts to proteins on the surface of the virus and makes antibodies that are summoned the next time a similar virus tries to infect the body.

But the further away the new strain is genetically from the ones the body has previously been exposed to, the more different the surface proteins, the less effective the antibodies and the more likely that infection will take hold.

This is what the authors suggest happened to the young adults in the 1918 pandemic. In their childhood around 1880 to 1900, they were exposed to a supposed H3N8 virus that was circulating in the population. This virus had surface proteins that were very different from those of the H1N1 pandemic strain. Their immune system would have made antibodies, but they would have been ineffective against the H1N1 virus.

But people born either before or after those decades would have been exposed to a virus much more like the 1918 one and their immune systems were thus better equipped to fight it.

Prof. Worobey notes:

“We believe that the mismatch between antibodies trained to H3 virus protein and the H1 protein of the 1918 virus may have resulted in the heightened mortality in the age group that happened to be in their late 20s during the pandemic.”

He says their finding may also help explain differences in patterns of mortality between seasonal flu and the deadly H5N1 and H7N9 bird flu viruses.

The authors suggest perhaps immunization strategies that mimic the often impressive protection that early childhood exposure provides could dramatically reduce deaths from seasonal and new flu strains.

In February 2014, Prof. Worobey and colleagues began challenging conventional wisdom about flu outbreaks, when in the journal Nature, they reported the most comprehensive analysis to date of the evolutionary relationships of flu virus across different host species over time.

Among other things, they challenged the view that wild birds are the major reservoir for the bird flu virus. Instead of spilling over from wild birds to domestic birds, they say the more likely scenario is the other way around - that new strains jump from domestic to wild birds.

read more:

http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/276060.php

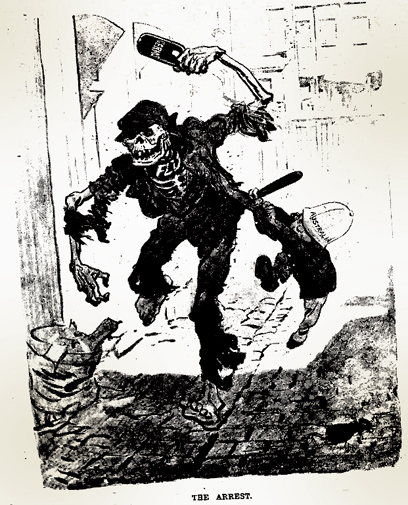

Picture at top from The Bulletin 1919, by David Low. See also: http://spartacus-educational.com/Jlow.htm

- By Gus Leonisky at 26 Aug 2017 - 6:22am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

and the cat...

Influenza A viruses are found in many different animals, including ducks, chickens, pigs, whales, horses, seals and cats.

Influenza B viruses circulate widely only among humans.

Influenza A viruses are divided into subtypes based on two proteins on the surface of the virus: the hemagglutinin (H) and the neuraminidase (N). There are 18 different hemagglutinin subtypes and 11 different neuraminidase subtypes. All known subtypes of influenza A viruses have been found among birds, except subtype H17N10 and H18N11 which have only been found in bats. Below is a table showing the different hemagglutinin and neuraminidase subtypes and the species in which they have been detected.

Aquatic birds including gulls, terns and shorebirds, and waterfowl such as ducks, geese and swans are considered reservoirs (hosts) for avian influenza A viruses. Most influenza viruses cause asymptomatic or mild infection in birds; however, clinical signs in birds vary greatly depending on the virus. Infection with certain avian influenza A viruses (for example, some H5 and H7 viruses) can cause widespread, severe disease and death among some species of birds. Avian influenza A viruses are designated as highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) or low pathogenicity avian influenza (LPAI) based on molecular characteristics of the virus and the ability of the virus to cause disease and mortality in chickens in a laboratory setting.

Pigs can be infected with both human and avian influenza viruses in addition to swine influenza viruses. Infected pigs exhibit signs of illness similar to humans, such as cough, fever and runny nose. Because pigs are susceptible to avian, human and swine influenza viruses, they potentially may be infected with influenza viruses from different species (e.g., ducks and humans) at the same time. If this happens, it is possible for the genes of these viruses to mix and create a new virus.

An example of reassortment is the Asian lineage H7N9 virus. The eight genes of the H7N9 virus are closely related to avian influenza viruses found in Asian domestic ducks, wild birds and domestic poultry. Experts think multiple reassortment events led to the creation of this H7N9 virus. These events may have occurred in habitats shared by wild and domestic birds and/or in live bird/poultry markets, where different species of birds are bought and sold for food. As this diagram shows, the Asian H7N9 virus likely obtained its HA (hemagglutinin) gene from domestic ducks, its NA (neuraminidase) gene from wild birds, and its six remaining genes from multiple related H9N2 influenza viruses in domestic poultry

read more:

https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/viruses/transmission.htm

2017 — a bad flu season...

This year, the number of laboratory-confirmed flu virus infections began rising earlier than usual and hit historic highs in some Australian states.

If you have been part of any gathering this winter, this is probably not news.

States in the south-east (central and southern Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia) are more inflamed by flu than those in the north and west.

For example, Queensland has seen more hospital admissions than in the last five years, mostly among an older population, while younger demographics more often test positive without needing hospitalisation.

read more:

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-08-21/flu-influenza-why-2017-has-been-a-...

2020 — a coronavirus...

From Kit Knightly

The Coronavirus is still the big-ticket news item, with confirmed cases now covering 11 countries. ELEVEN!

Most of the mainstream media are doing that, saying the number of countries rather than the number of people. I suppose because it carries the implication that, somehow, everyone in all those 11 countries is under some kind of imminent threat.

As of the time of writing, the real (or at least reportedly real) numbers stand at 1407 cases, 41 deaths. Which means the mortality rate is now actually below 3%.

For comparison’s sake – the death rate of the Ebola virus is 90%, Bubonic plague 40-60%, Smallpox was ~30%, and the 1918 Spanish flu between 10 and 20%. So we’re hardly dealing with a big-hitter here.

Even the hysterical-nothing burger that was SARS had a (reported) death rate approaching 10%. [For more on the links between SARS and the Wuhan outbreak see John Rappoport’s excellent work on the subject].

For anyone doubting that, whatever the truth of the situation on the ground, this is being hyped to spread fear: The Guardian has a big red “LIVE BLOG” for the disease today. Counting up the death toll very slowly, and with what I would call a rather unseemly amount of enthusiasm.

China are building a whole new hospital, we’re being told. There are “bodies in the streets”, apparently...

The Daily Mail is reporting that an Australian research team is “racing against the clock” to engineer a vaccine. The researchers claim it will take them 6 months (a very fast turnaround for vaccine development, which usually takes years).

If the disease carries on its current trajectory, by the end of that six months roughly 7200 people will have been infected, around 250 of whom will have died.

In the same timeframe, about 15,000 people will have been injured in car accidents, and around 900 of them will have died…in the UK alone.

Based on that, you could argue the resources poured into the “race against time” would be better spent inventing stronger seat-belts or funding an anti-drink driving campaign.

After all, any good this hypothetical vaccine might do needs to be off-set against the potential dangers of injecting thousands – even millions – of people with a vaccine that will have had no long term safety studies whatsoever.

Of course, The Daily Mail doesn’t mention that.

Another thing The Daily Mail doesn’t mention is that the vaccine being developed by Queensland University is a cooperative project with Philadelphia-based Inovio Pharmaceuticals, who received a grant of $9 million to combat the Wuhan outbreak.

A second pharmaceutical firm, Co-Diagnostic Inc, has received a similar grant to develop a coronavirus “screening test”.

Inovio previously hit the headlines a few years ago, when they received a grant to create an anti-Zika vaccine (something they managed to do in less than six months).

The grants were distributed by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), an NGO that promotes global vaccination and is funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation(among others).

Inovio’s stock jumped 12% when it was announced they had been commissioned to manufacture the vaccine, whilst Co-Diagnostic’s stock almost doubled in value following the news :

[Co-Diagnostics Inc.’s stock] nearly doubled (up 80%) to a one-year high. Trading volume shot up to 36.1 million shares, compared with the full-day average of about 161,000 shares.

But that’s just the beginning. The CEO of Co-Diagnostics sees a much bigger windfall down the line (our emphasis):

Chief Executive Dwight Egan said in a statement that if the World Health Organization declares the illness a global health emergency, he believes Co-Diagnostics would be in position to “quickly assist” in providing its test to the affected countries.

Note the bolded.

Whatever else is going on, however real or otherwise this “outbreak” proves to be, “if the WHO declare a global health emergency”, some people are going to make a lot of money.

Read more:

https://off-guardian.org/2020/01/25/coronavirus-update-following-the-money/

Read from top.

an unfortunate bear necessity...

A mass teddy bear hunt is under way around the world to help distract the millions of children locked down because of the coronavirus pandemic.

Stuffed toys are being placed in windows to give children a fun and safe activity while walking around their neighbourhood with parents.

The hunt is inspired by the children’s book We’re Going on a Bear Hunt, written by UK author Michael Rosen.

Teddies have been spotted around the world, including in the UK and US.

New Zealand’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has also joined in, putting two bears in the window of her family house in Wellington.

Tanya Ha, a resident of Melbourne in Australia, told the BBC she had been inspired to put cuddly toys in her window after hearing about other hunts around the world.

Read more:

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-52108765

Read from top.

The situation is serious. The stock market has gone to the bear...

From the SMH...

mask up!...

According to The New York Times, during the pandemic, Boy Scouts in New York City approached people they’d seen spitting on the street and gave them cards that read: “You are in violation of the Sanitary Code.”

Aspirin Poisoning and the FluWith no cure for the flu, many doctors prescribed medication that they felt would alleviate symptoms… including aspirin, which had been trademarked by Bayer in 1899—a patent that expired in 1917, meaning new companies were able to produce the drug during the Spanish Flu epidemic.

Before the spike in deaths attributed to the Spanish Flu in 1918, the U.S. Surgeon General, Navy and the Journal of the American Medical Association had all recommended the use of aspirin. Medical professionals advised patients to take up to 30 grams per day, a dose now known to be toxic. (For comparison’s sake, the medical consensus today is that doses above four grams are unsafe.) Symptoms of aspirin poisoning include hyperventilation and pulmonary edema, or the buildup of fluid in the lungs, and it’s now believed that many of the October deaths were actually caused or hastened by aspirin poisoning.

How U.S. Cities Tried to Stop The 1918 Flu Pandemic

A devastating second wave of the Spanish Flu hit American shores in the summer of 1918, as returning soldiers infected with the disease spread it to the general population—especially in densely-crowded cities. Without a vaccine or approved treatment plan, it fell to local mayors and healthy officials to improvise plans to safeguard the safety of their citizens. With pressure to appear patriotic at wartime and with a censored media downplaying the disease’s spread, many made tragic decisions.

Citizens in San Francisco were fined $5—a significant sum at the time—if they were caught in public without masks and charged with disturbing the peace.

Spanish Flu Pandemic EndsBy the summer of 1919, the flu pandemic came to an end, as those that were infected either died or developed immunity.

Read more:

https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-i/1918-flu-pandemic

Read from top.