Search

Recent comments

- cancelled....

32 sec ago - "concerns"......

3 min 38 sec ago - list of 20....

8 min 1 sec ago - "alternative"...

1 hour 32 min ago - rubio's war....

2 hours 39 min ago - not laughing...

2 hours 56 min ago - crying over war....

3 hours 3 min ago - pillage and rape.....

3 hours 9 min ago - sino-innov....

16 hours 37 min ago - the star mangled banner....

18 hours 37 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

killer codes .....

The capture of the Enigma code machine 70 years ago changed the course of the second world war. But the secret codes broken by this event were not history's toughest ciphers. Plenty of codes are uncracked and, as MacGregor Campbell discovers, their solutions may provide the key to murders or even buried treasure

The Somerton Man

On a warm summer's night in 1948, witnesses saw a well-dressed man lying on the beach in Somerton, near Adelaide, South Australia. By 6.30 the next morning, the man had not moved. He was dead.

An autopsy revealed organ damage consistent with poisoning, but no foreign substances in his body. He carried no identification. Fingerprint and dental-record searches came back with nothing. His clothes had no labels and were heavy for a night so balmy, suggesting he was not a local.

Thus was born the legend of the Somerton Man. It remains one of the most mysterious unsolved deaths in Australian history. To this day, we don't know who he was. A well-dressed drunk? A forlorn lover? A Russian spy? There is no shortage of theories, but facts are scarce. He did, however, leave behind a code.

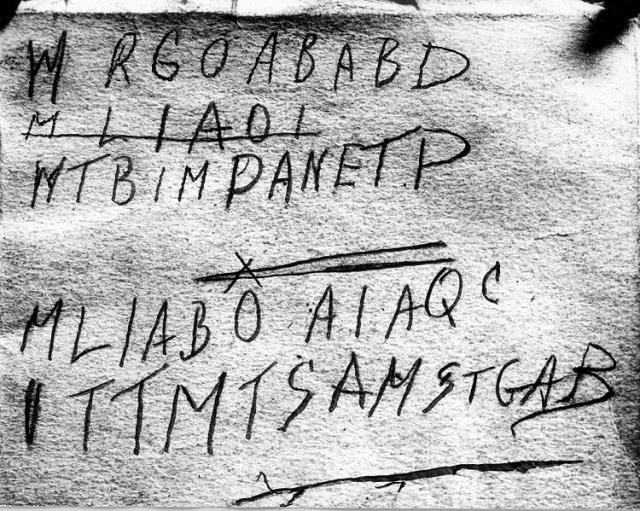

Six months after the body was found, investigators discovered a small scrap of paper in a concealed pocket in his trousers. It read, simply, "Tamam Shud" - Persian for "ended". When investigators announced this find, it generated a new lead. Shortly after the death, a man who had parked his car and left it unlocked near the beach on the night Somerton Man was discovered found a copy of Persian poet Omar Khayyam's The Rubaiyat in his car. The last page had a piece torn out of it that matched the mystery scrap in the Somerton Man's trousers. In the back of the book was a lettered code, scrawled over a few lines (pictured above).

Eventually all other leads pursued by the police came to dead ends, so this unsolved code is one of the few remaining clues that might yet reveal the man's identity.

Derek Abbott at the University of Adelaide is leading the most recent effort to untangle the mystery. His main approach uses software originally designed to identify the author of unknown texts. "My goal was not to crack the code, but to take a step back and apply statistical techniques to rule out which type of cipher techniques the Tamam Shud code is definitely not," he says.

He applied a simple "frequency analysis", a technique that involves counting the number of times each letter appears and that can spot the signatures of certain methods of coding. Though the brevity of the code makes it hard to be sure, Abbott and his team ruled out 20 different code types.

Abbott also claims to have ruled out the possibility that it is gibberish. His team had 30 people write random collections of letters and compared the results to the code. "The statistics of the letters show that the code bears structure and information content," he says.

His current theory is that the code is composed of the first letters of English words. The team is searching for patterns of words in e-books, looking for common passages that may have been used in the hidden message. They hope to soon expand their search to the entire web.

Abbott says that a faster route to figuring out the man's identity would be to exhume the body and analyse the DNA and the isotopes present in his bones. "The bone isotope test will reveal where he was born. With DNA we can find which family tree he belongs to." But unless he can persuade the police to take a fresh look at the case, the code is all we have to go on to solve this enduring mystery.

A grisly find on Somerton beach (right), triggered a search for the identity of a dead man who left some baffling clues

In 1885, James B. Ward published The Beale Papers, a pamphlet containing three coded messages, the solution of which, Ward claimed, would lead to sizeable buried treasure in Bedford county, Virginia.

According to the pamphlet, 60 years earlier the eponymous Beale left a small locked box containing the codes with an innkeeper before disappearing. The innkeeper passed the messages to a friend, who solved only one of the puzzles - the one detailing the vast riches awaiting whomever could solve the other two.

The solved code featured numbers that corresponded to the initial letters of the words in the US Declaration of Independence. The code was a string of numbers, so 12, for example, referred to the first letter of the twelfth word in the Founding Fathers' text.

In 1980, Jim Gillogly used a computer to decode one of the remaining unsolved codes. He found a number of anomalies, such as long strings of characters in alphabetical order, suggesting they are a hoax.

There have been many subsequent efforts to find the treasure - and even a Hollywood movie called National Treasure inspired by the tale - but Gillogly has seen nothing in the past 30 years to make him doubt his original assessment. "I'm quite confident that they're a hoax," he told New Scientist.

Nestled in the archives at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology is a metre-tall container made of lead. Its specific contents are a mystery to be revealed only when an accompanying encrypted message is solved. Only one man has the solution: Ron Rivest, coinventor of the RSA algorithm, one of the most ubiquitous methods for encrypting online communications.

To celebrate his lab's 35th anniversary in 1999, Rivest devised a "time-lock" puzzle inspired by his algorithm. Only when the solution is revealed, his rules state, may the lead bag be opened. He estimated it would take 35 years to solve - unless somebody could find a shortcut.

Rivest's coded message is hidden in 616 numbers. The method of encryption differs from an alphabet-based code, in which each letter matches another. It involves converting numbers into their binary form after solving a heinously difficult mathematical problem.

The problem that Rivest devised is simple to state: divide one number over 7.2 quadrillion digits long - 2279685186856218 - by a second number over 600 digits long. Then find the remainder.

The remainder, also over 600 digits long, is the "key" to unlocking the code. The codebreaker must convert it to binary form - a series of 1s and 0s - and compare it with a binary version of the 616 numbers of the original code. This comparison procedure is used to create a third string of binary: when the 1s and 0s match, that equals a 0; when they don't, that's a 1. Then you're almost there: since binary can also represent the alphabet, the codebreaker would translate this third string of binary into the letters of the secret message.

So why would that take 35 years to solve? Rivest designed the initial division problem to be so big that it would take three decades of continuous computation to calculate - and that's assuming that computing speed doubles roughly every two years, as predicted by Moore's law. The calculation can only be done in sequential steps, says Rivest, making it invulnerable to distributed computer networks or the parallel processors used in supercomputers.

In theory though, there could be a shortcut. The second 600-plus-digit number in the calculation is the product of two large prime numbers. If these could be found, the computation could be completed in much less time, because a different mathematical technique could be applied.

Finding those factors would be no mean feat, however. The difficulty of factoring products of two large primes is the core mathematical fact underlying RSA encryption, a widespread method to allow two parties online to communicate securely without both of them needing a secret key. Rivest developed it in 1977 along with Adi Shamir and Len Adleman.

For example, if Alice wished to send Bob a secure message, she could ask him for a number and do a relatively simple and non-reversible calculation to encrypt the message. That number, the message's "public key" is not secret. It is essentially the product of two large prime numbers. Only Bob can decrypt the message, because only he knows what the two primes are. The largest public key number ever "broken" into its two primes was achieved by a team led by Thorsten Kleinjung at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne. It was 232 digits long, so it wasn't close to the size of the 600-plus-digit number in Rivest's puzzle.

Rivest told New Scientist that he thinks his original estimates of how long the puzzle would take may be too optimistic. "Computing power isn't increasing quite as fast as predicted, in terms of ability to do fast sequential computations," he says. Barring a breakthrough in the art of factoring, decrypting the message will likely take longer than expected.

Still, Rivest has underestimated codebreakers in the past. In 1977, he helped to design a puzzle for Martin Gardner's recreational mathematics column in Scientific American. The solution to the puzzle required factoring a 129-digit number. Nobody managed it at the time, but in 1991 a team of 600 volunteers did it in eight months, helping to reveal the message: "The Magic Words Are Squeamish Ossifrage." (Ossifrage is the name of a type of vulture, and means "bone-breaker".) Rivest and colleagues had estimated, based on the computing power of the time, that the task would take 40 quadrillion years.

The Kryptos statue at the CIA has stumped the agency's best codebreakers

At the US Central Intelligence Agency's headquarters in Langley, Virginia, there is a monument to secrecy that has vexed both professional and amateur codebreakers for over two decades.

Erected in 1990, the Kryptos sculpture is a copper artwork bearing 1735 coded letters. Its creator is American artist James Sanborn, who received cryptography training from a CIA code expert. The sculpture's code is divided into four sections. Three have been broken, revealing enigmatic messages that hint at a wider mystery, but the fourth and final section has yet to be cracked.

Sanborn has hinted that the clues to unlocking it lie in the first three sections, which a Californian computer scientist named Jim Gillogly announced he had solved in 1999. (Shortly after, the CIA announced that one of their analysts, David Stein, had solved the same sections in 1998, with pencil and paper.)

The first two sections were encrypted using a modified form of a Vigenère cipher. This draws on the same basic principles of letter-for-letter substitution as basic codes like Caesar ciphers in which, say, B equals A, C equals B and so on. However, the Vigenère technique encrypts letters by placing alphabets in a grid, called a tabula recta. Each letter in the message could be encoded using any one of 26 different columns.

Like many codes, to crack it you need first to find a secret keyword. This word doesn't reveal the message by itself, but it tells you which column to use to decipher each letter of the code (see diagram, right).

In the case of the modified Vigenère used in Kryptos, the keywords KRYPTOS and PALIMPSEST told the crackers a procedure for rearranging the alphabets in the tabula recta. These keywords were discovered by a combination of letter frequency, clues written into in the sculpture and trial-and-error.

The sculpture's first section translates into the message: "Between subtle shading and the absence of light lies the nuance of iqlusion." The second section - which also contains deliberate spelling mistakes - hints at the mysterious burial of a secret object.

A different method was used to reveal the message in the third section. Before it could be decoded, every fourth column of letters in the sculpture itself first had to be shifted to the left, then the rows shuffled. The solution was an adaptation of Howard Carter's account of the opening of Tutankhamun's tomb.

Plenty of speculation surrounds how these answers and coding methods might relate to the unsolved final part, but nobody has yet worked out the answer. In November 2010, Sanborn revealed the solution for six of the letters in the unsolved code: "Berlin".

"It had been a long time, and a lot of people needed some encouragement," Sanborn told New Scientist. His website received about 10,000 guesses in the first few weeks after the announcement, but the pace has since slowed down to about 10 solutions per day. Sanborn says many people make random guesses at the underlying message.

Others are taking a more reasoned approach. Robert Matson, a member of the largest online group dedicated to solving Kryptos, recently found a way to yield "Berlin" from the code, using a Vigenère method. The solution does not, however, give intelligible text for the rest of the unsolved code, leading some to suspect that there is either another layer of encryption, or that it's a blind alley.

Elonka Dunin, co-leader of the group, seeks clues in Sanborn's other artworks. The sculptor's Antipodes, for example, depicts two codes, one written in the Russian alphabet, the other a near-identical copy of the coded sections featured in Kryptos. "Any time I travel, I check to see if there are any Jim Sanborn works in the area," she says.

She might be onto something. When Sanborn created the decor for Zola's Spy Restaurant at the Spy Museum in Washington DC, he hid references to Kryptos and his other works. Before it was deciphered in 2003, the solution to his coded sculpture called Cyrillic Projector went unnoticed on the wall. It was the partial text of a KGB document.

Such methods may have to suffice: Sanborn says he's not announcing more clues any time soon. "It's going to only be once every decade or two," he says.

As inscrutable codes go, few inspire as many imaginative interpretations as the Voynich manuscript, a medieval tome filled with illustrations of medicinal plants, astrological diagrams, naked nymphs and pages of indecipherable script. Despite a century of effort by some of the greatest cryptanalysts, not a word has been decoded.

Little is known about the book's history prior to 1912, when book dealer Wilfrid Voynich found it in an Italian monastery, though it is believed to have belonged to the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II of Bohemia.

In 2004, computer scientist and linguist Gordon Rugg at the University of Keele, UK, published a persuasive argument that the manuscript is, in fact, nonsense. This contradicted previous researchers, who had noted that the pattern of word lengths and symbol combinations was similar to structures found in real languages, a match that would be difficult for a forger to replicate. But Rugg showed that it would be possible to create a nonsense similar to that found in the manuscript using techniques known to 16th-century cryptographers (Cryptologia, vol 28, p 31).

Andreas Schinner at Johannes Kepler University in Linz, Austria, published a study supporting this interpretation in 2007. He found that the statistical properties of the script are consistent with gibberish (Cryptologia, vol 31, p 95).

It is certainly old, however. In 2009, radiocarbon dating pinned down the age of the book's vellum to the mid-15th century. If the age was more recent, a fake would be certain.

Schinner says this does not rule out a hoax, but concedes that it is not possible to prove mathematically that the text does or does not hold meaning.

The second world war brought a shift from handwritten cryptography to machines capable of spinning up complex, ever-changing codes. The best known of these was the Enigma machine, first used by the German navy in 1926.

Enigma machines used three or four mechanical rotors to scramble electrical circuits that assigned the letters of the message to be encrypted into letters of coded text. The rotor settings were changed regularly, often every day, meaning that messages seldom shared the same encryption. With the help of Alan Turing, and early computers called Bombes, Allied codebreakers eventually cracked many Enigma messages, which helped to turn the tide of the war. Many messages, however, were never broken.

In 2006, Stephen Krah, an amateur codebreaker based in Utrecht, the Netherlands, began an effort to crack three such Enigma messages intercepted by HMS Hurricane in the north Atlantic in 1942. Like SETI@home, which seeks to harness spare home-computer capacity to analyse signals from space for signs of intelligent life, Krah's Enigma@home harnesses thousands of computers around the world to help crack the codes. The project solved the first two messages in a matter of months - describing a submarine location report and how a crew was forced to submerge after coming under attack. The third has yet to be cracked.

David Kahn, author of The Code Breakers, an oft-cited history of cryptography, says it is not surprising that an Enigma message has withstood such a large computational attack. The Allies only broke Enigma transmissions by taking educated guesses at the solution, then using Bombes to generate possible settings that yielded the encrypted text. Without an educated guess as to the content, he says, there are too many combinations of wheel settings to break Enigma in a human lifetime.

The English composer Edward Elgar was a keen cryptographer. The melody of his Enigma Variations - for which the German enciphering machines were named - is supposedly complementary to the melody of a famous song by another composer. He didn't say which.

This melodic mystery is not the only surviving Elgar puzzler. In 1897, he wrote an 87-character code to his friend Dorabella Penny. Forty years later, she published the code in her memoirs but claimed never to have solved it.

In the intervening years, many would-be codebreakers have also drawn a blank. The script appears to contain 24 distinct squiggly symbols spread across three lines. Analysis of the code suggests the symbols could be a simple "substitution cipher", where each symbol is assigned to a letter. But this hasn't produced an answer, so perhaps it is a shorthand language shared only between Elgar and Penny.

In 2007, the Elgar Society organised a competition to break the code. Alas, none of the entries was convincing.

Famous for peace, love, and tie-dye, San Francisco in the late 1960s was also the setting for one of the creepiest real-life murder mysteries in American history. From December 1968 to October 1969, a serial killer using the moniker "Zodiac" murdered at least seven people. The killer taunted local police and newspapers with handwritten letters containing threats, claims of further undiscovered victims, and coded messages.

The supposed killer claimed that the solutions would reveal an identity when they were all solved. Some never were, and the killer was never caught.

The first three codes were encrypted by replacing letters with symbols. But there was a twist: some of the more frequent letters, like "e", were assigned to multiple symbols. This made it difficult to solve by simple codebreaking techniques like looking for more commonly used letters.

The three were eventually cracked by supposing that the words "kill" or "killing" would be in the message. When the results were combined, they formed a single, longer message that described the pleasure the murderer took in killing and described a motivation based on supernatural forces, but no clues as to his or her identity.

In November 1969, Zodiac sent a code to the local papers that law-enforcers still believe could hold the key to solving the case. At 340 characters, it is shorter than the first three codes, and didn't use the same encryption method. Dan Olson, chief of the US Federal Bureau of Investigation's Cryptanalysis and Racketeering Records Unit, says the code, known as Z-340, is number one on his unit's internal "top 10" list of unsolved codes. He says he gets 20 to 30 submissions from the public every year, but these haven't led to any breakthroughs in the case.

Bureau cryptanalysts have measured the distribution of symbols in the code to see if it could be shown that a message is indeed present. If there was no solution, or if it was scrambled beyond recognition, then the distribution of the characters in the rows should be equal to the distribution of those in the columns, but that isn't the case.

In 2009, Ryan Garlick, a computer scientist at the University of North Texas in Denton, along with his students, tried to "evolve" a solution using so-called genetic algorithms. They first randomly generated possible pairings of English letters with symbols from the code. They then looked for how well a given set of pairings of Zodiac symbols and English letters produced two and three-letter sequences in the potential solution, like "th" and "es", which are common in English.

The best-performing pairings were subjected to further selection and recombination. Using this method, they were able to evolve the solution to the first, solved, Zodiac message, but made little progress with Z-340. Subsequent attempts with genetic algorithms by researchers at San Jose State University in California have yielded similarly disappointing results.

Garlick suspects that some sort of physical rearrangement of the ordering of the symbols is necessary. Testing all the possible ways this could be done, however, is daunting. "You have to happen upon exactly the right thing before any of our software tools would even get close," he says.

Zodiac sent a coded message (right) to a newspaper after killing someone by a lake (below)

MacGregor Campbell

- By John Richardson at 10 Apr 2013 - 11:07pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

the kgb in australia...

... based on a book of D. Ball and D. Parker "Breaking The Codes"

The majority of the KGB agents were communists or people of the left political orientation. As well as the majority of foreign communist parties, in the 1930-ties the CPA stood on firm Stalinist positions. In 1939 CPA declared anti-fascist slogans, but after the conclusion of the non-aggression pact between the USSR and Germany it declared the World War II as "imperialistic" and took a defeatist anti-British position despite the fact that Australia had joined Great Britain in the war against Hitler. Thereof in 1940 the CPA was declared as an outlaw organization by the authorities. After the 22nd of June 1941 the CPA again rapidly changed its policy and called for a close union with the USSR in the war of democratic nations against the fascist aggression.

In December 1942, the interdiction on the CPA activity was cancelled. The successes of the Soviet Army greatly increased popularity of the CPA and by December 1944 the number of its members had increased up to 23-24 thousand people. Four thousand communists served in the Australian army, party cells existed even in staff units. However, at the confidential meetings of the top of the party its anti-imperialistic views were still expressed, the preference was given to the Russian victory, not necessarily to the victory of the allies. Firm communist pro-Soviet positions played a main role in the turn of some communists to espionage in favor of the USSR.

read more http://australiarussia.com/Klod1ENFIN.htm

Though the book is unavailable at many online resellers, at Amazon.com it will cost you a hefty $380.00. A copy of the book fell from the back of a truck into my mittens in 2001, and now this work proudly sits alongside J C Masterman's the Double Cross System, given to me by a former agent, and other illuminating real spy stories that shine a small torch-light on the cave of deception that is the size of the universe... We have three lumens when we need ten gazillion candles... This is where Wikileaks shines above any other revealing sources, but plodding through the diplomatic vomit is hard yakka...

and they can read your number plates but that's classified...

http://www.youtube.com/embed/13BahrdkMU8?

spies and media in grey economic areas...

We always ridicule the 98 percent voter support that dictatorships frequently achieve in their elections and plebiscites, yet perhaps those secret-ballot results may sometimes be approximately correct, produced by the sort of overwhelming media control that leads voters to assume there is no possible alternative to the existing regime. Is such an undemocratic situation really so different from that found in our own country, in which our two major parties agree on such a broad range of controversial issues and, being backed by total media dominance, routinely split 98 percent of the vote? A democracy may provide voters with a choice, but that choice is largely determined by the information citizens receive from their media.

Most of the Americans who elected Barack Obama in 2008 intended their vote as a total repudiation of the policies and personnel of the preceding George W. Bush administration. Yet once in office, Obama’s crucial selections—Robert Gates at Defense, Timothy Geither at Treasury, and Ben Bernake at the Federal Reserve—were all top Bush officials, and they seamlessly continued the unpopular financial bailouts and foreign wars begun by his predecessor, producing what amounted to a third Bush term.

Consider the fascinating perspective of the recently deceased Boris Berezovsky, once the most powerful of the Russian oligarchs and the puppet master behind President Boris Yeltsin during the late 1990s. After looting billions in national wealth and elevating Vladimir Putin to the presidency, he overreached himself and eventually went into exile. According to the New York Times, he had planned to transform Russia into a fake two-party state—one social-democratic and one neoconservative—in which heated public battles would be fought on divisive, symbolic issues, while behind the scenes both parties would actually be controlled by the same ruling elites. With the citizenry thus permanently divided and popular dissatisfaction safely channeled into meaningless dead-ends, Russia’s rulers could maintain unlimited wealth and power for themselves, with little threat to their reign. Given America’s history over the last couple of decades, perhaps we can guess where Berezovsky got his idea for such a clever political scheme.

read more: http://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/our-american-pravda/

Gus guess: Australia?