Search

Recent comments

- meanwhile.....

9 hours 16 min ago - young losers....

9 hours 51 min ago - bulgarian slow train....

9 hours 57 min ago - a six-minute read...

12 hours 54 min ago - inexpensive....

14 hours 47 min ago - obviously....

14 hours 53 min ago - macronleon de gaulle.....

17 hours 12 min ago - nazis in washington.....

17 hours 20 min ago - blinkenings.....

1 day 55 min ago - georgia's NGOs

1 day 1 hour ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

inside, pissing out .....

In the hit Broadway musical How to Succeed in Business without Really Trying, a young window washer discovers a book that tells him the secrets to climbing the corporate ladder.

If such a book were to exist in Australia, it would be short, consisting of one sentence: ''Become the CEO of a company with monopoly power.''

Australia's top 10 biggest companies, by the value of their shares listed on the ASX, comprise four banks, three mining companies, a telecommunications company, a shopping centre owner and a grocery store.

All of these companies derive their value, in some way, from the presence of a degree of monopoly power. Miners have monopoly power over particular mines, awarded by exploration licences. Telstra has a monopoly over the copper wire network for telecommunications. Westfield controls land and land has scarcity power. Woolworths owns stores in prime locations all over Australia.

And the banks exist as a cosy club of four, locking customers into 25-year loans that are a hassle to transfer.

Monopolistic companies possess a power that is envied by every business person: the ability to set their prices above their costs of production.

In a truly competitive market, consisting of many sellers selling a similar product, firms don't actually control their prices. They are ''price takers''. Prices are determined by the intersection of supply and demand, and because no one seller has enough market power, they can't influence the price. They just keep producing until their cost of producing one extra unit equals the market price.

If this all sounds a bit foreign, that's because many of the markets for the products we consume are tainted by a degree of market power. Girt by sea, Australia has proved a breeding ground for monopolies, or oligopolies.

Pure monopolies, where one firm is the sole seller of a product without close substitutes, are quite rare. They arise when a key resource is owned by one firm, the government gives a single firm exclusive rights to produce a product, or the costs of production make a single producer more efficient than a large number of producers.

Oligopolies, however, abound. Think of groceries and you see the market dominated by two players - Woolworths and Coles. Think petrol and you get Caltex, BP, Shell and Mobil. Think banks: Commonwealth, Westpac, NAB and ANZ. Think telecommunications: Telstra and Optus. And of course, think airlines and you get Qantas and Virgin.

It's hard to turn around without seeing the corporate logo of some oligopolist. No wonder we Australians so often feel like we're getting ripped off, either paying more than we should in a truly competitive market or simply not getting the service that we deserve.

Trade liberalisation has opened up opportunities for cheaper imports of many everyday items such as TVs, fridges, couches and cars. When goods are internationally traded it is harder for monopolies to survive.

But many of our big purchases, groceries, electricity and home loans continue to be supplied by a limited number of domestic companies and so we need to be constantly vigilant to the presence of monopoly power.

One of the main jobs of an Australian government, then, is to stand up against these oligopolists and try as much as possible to expose them to the rigors of competition.

Banks must be bashed, telecommunication monopolies dismantled and cosy monopolists forced to provide a good product, not just for shareholders but also customers.

The Rudd government ran several inquiries into the concentration of power in the grocery and petrol markets. The problem is, once an oligopoly exists, it's hard to unscramble the egg. Without creating new companies, like turning Australia Post into a bank, the best that can be done is to ensure barriers to entry are as low as possible. Market power is lessened if participants are opened to competition from foreign competitors. But where the product sold is a key strategic resource, such as the telecommunication or electricity networks or mines, opportunities for opening up the industry to foreign competition are limited.

Oligopolistic competition is, then, an enduring feature of the Australian business landscape. And the rewards can be handsome.

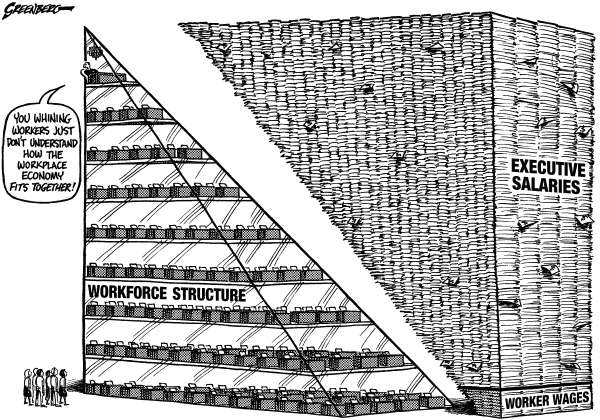

Alan Joyce, the CEO of Qantas, which has a near-monopoly over air travel in Australia, has hit the headlines with his $5 million pay packet. But he is far from the highest paid CEO in Australia.

Top of the list for 2010 was the outgoing Commonwealth Bank boss Ralph Norris, on $16.2 million. ANZ's Mike Smith also makes the top 10, as does Westpac's Gail Kelly on $9.6 million and Macquarie Group's Nick Moore (an unfortunate name) on $9.6 million. In fact, of the 10 largest companies in Australia, eight also have CEOs in the top 10 of highest paid executives.

Economic theory says workers are paid according to the value of their marginal product. But what are the bank CEOs adding?

It is hard to escape the conclusion that many of their salaries derive not from the value added by the CEOs but the monopolistic power those companies exert over the prices paid by the Australian consumer.

Australian CEOs say they must be remunerated so as not to be tempted away by jobs as international CEOs. But running a company is a tougher gig in the big, deeper pools of larger economies. Better to be a big fish in a small pond.

CEOs also say they need to be compensated for the risks involved in running these very large companies. But what risk? Running a big bank in Australia is about as risky as running a large bureaucracy, and we don't pay public servants anything like these guys get. The membership of the top 10 companies in Australia is remarkably stable. These are not companies that fall over. In fact, the big four banks have an all but explicit guarantee they will not be allowed to fail.

Sitting in a CEO chair at the top of the ASX food chain is a great gig. These companies are simply not at risk of going under and their CEOs simply don't deserve what they get.

- By John Richardson at 2 Nov 2011 - 8:37am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

the lucky bonuses...

From George Monbiot

If wealth was the inevitable result of hard work and enterprise, every woman in Africa would be a millionaire. The claims that the ultra-rich 1% make for themselves – that they are possessed of unique intelligence or creativity or drive – are examples of the self-attribution fallacy. This means crediting yourself with outcomes for which you weren't responsible. Many of those who are rich today got there because they were able to capture certain jobs. This capture owes less to talent and intelligence than to a combination of the ruthless exploitation of others and accidents of birth, as such jobs are taken disproportionately by people born in certain places and into certain classes.

The findings of the psychologist Daniel Kahneman, winner of a Nobel economics prize, are devastating to the beliefs that financial high-fliers entertain about themselves. He discovered that their apparent success is a cognitive illusion. For example, he studied the results achieved by 25 wealth advisers across eight years. He found that the consistency of their performance was zero. "The results resembled what you would expect from a dice-rolling contest, not a game of skill." Those who received the biggest bonuses had simply got lucky.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2011/nov/07/one-per-cent-wealth-destroyers

I knew that...

why not .....

There is no doubt that today's report from the High Pay Commission will strike a chord with many people - and not just the increasing numbers of protesters supporting such campaigns as Occupy London. The decoupling of executive pay from the remuneration of the rest of the workforce began well before the credit crunch, but in an age of austerity, widening inequality is all the more divisive.

Still, these issues are deceptively simple. The first challenge for the High Pay Commission and other campaigners is to decide what really worries them. Is it the absolute level of the rewards paid to senior executives, or the way in which those rewards are decided?

In the case of the High Pay Commission, it appears to be mostly the latter. Most of the reforms it suggests (though not all) would require companies to think much harder about how the pay of their management is decided upon. That is not the same thing at all as making a bald assertion that there is such a thing as a salary that is too high.

In that sense, today's report will disappoint many people - those whobelieve it is simply wrong for, say, Barclays' Bob Diamond, pictured, to earn £4.3m, 169 times more than the average British worker. But pay reform requires realism: even if, as the High Pay Commission points out, the ratio between the pay of the boss of Lloyds Bank and his average employee has risen from 14 to 75 over the past 30 years, it seems highly unlikely this Government - or any future one - would place a legal cap on such a measure, let alone set maximum salary levels.

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/comment/david-prosser-ducking-the-really-tough-call-on-tackling-executives-runaway-remuneration-6265927.html

When I first started work more than 40 years ago, the annual salary of the managing director of my company was restricted to a multiple of 12 times the annual salary of the lowest paid person in the company.

In the organisation where I now work, the lowest paid person receives an annual salary of $45,000 which, based on the above metric, would mean the managing director should be being paid no more than $540,000 annually. The fact is, we probably wouldn't have a managing director if that was the real going rate.

Nevertheless, whilst I do believe that trying to restrict private sector remuneration to legislated levels represents an unacceptable intrusion into the workings of the market place, I have no problem with such restrictions being imposed on executive pay (in the public or private sector) where performance is a genuine issue or where the organisation is actively seeking to constrain the reasonable growth of their other employees' salaries & benefits.

I'm even more comfortable with the notion that such constraints should be mandatory where, due to the non-performance of a business, a government has decided to hand it assistance in the form of taxpayers' funds, in particular where the business plans to downsize its workforce at the same time.

Bluescope Steel is a classic recent example such a situation, where the company delivered a $1 billion dollar + loss, publicly announced that it was going to retrench 10,000 employees, was immediately offered a $100 million taxpayer funded gift by the federal government to "help them along", whilst deciding it would be a great idea to reward its CEO by paying him a bonus of $750,000 & his top 12 executives further bonuses of up to $3 million!!

This is an example of how bad our "system" has become ... "one where profits are privatised & losses are now socialised" & we just accept it.

Time to require our "fearless leaders" to stop the rorting of both shareholders & taxpayers by licensed bushrangers, going under a phoney guise of a "management elite".

a deep malaise ....

Vince Cable has welcomed a report which claims that executive pay is so over-the-top at some British companies that it is "deeply corrosive" to the economy.

"When pay for senior executives is set behind closed doors, does not reflect company success and is fuelling massive inequality, it represents a deep malaise at the very top of our society," says Deborah Hargreaves, chair of the High Pay Commission which published the report.

The report was paid for by a left-wing think tank, Compass, but according to The Guardian the Business Secretary's blessing means some of the recommendations could be picked up by the Government early next year.

Among them are:

The report gives specific examples of rocketing executive pay. In 1979, the senior executive at BP earned 16.5 times what the average employee earned. Today, he earns 63 times the average. At Barclays, top pay is now 75 times that of the average worker, while in 1979 the ratio was 14.5.

The report explodes the myth that high pay is necessary to prevent a talent drain. It observes that only one FTSE-100 chief executive was poached in five years - and this person went to another British company.

The Guardian says the Liberal Democrats are taking the High Pay Commission's report seriously. "Put it this way, this report is not going to be kicked into the long grass," said a party source.

Cable is reportedly keen to introduce legislation next year to curb excessive pay. "Many of the options we are consulting on are reflected in the High Pay Commission's final report," he said. A government consultation on the subject is due to end on Friday. ·

http://www.theweek.co.uk/uk-business/executive-pay/42868/cable-welcomes-report-which-slams-excessive-executive-pay?utm_campaign=theweekdaily_newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_source=newsletter

tipping point .....

Australia’s richest 1 per cent are grabbing a greater share of national income than at any time since the 1950s.

A new OECD report finds that Australian incomes were most evenly distributed at the end of the 1970s, when the top 1 per cent of earners took home 4.8 per cent of the income. Since the early '80s that proportion has climbed to 8.8 per cent, meaning Australia's top earners amass for themselves nine times as much income as if it was distributed evenly.

In almost all of the OECD countries surveyed income inequality was at its highest before World War I and fell sharply during World War II.

But whereas income inequality has remained low in mainland European countries and Japan since bottoming in the '70s, it has climbed since the '80s in the US, Australia, Canada, Ireland and Britain.

The surge has been dramatic in the US, which gave its top 1 per cent about 8 per cent of the national income at the turn of the 1980s and 18 per cent in the most recent reading.

Australia also stands out for how quickly all ranges have grown. Between the mid-1980s and the late 2000s the income enjoyed by the top 10 per cent of households has soared 4.5 per cent per year in real terms, more than in any other OECD member.

Income earned by the bottom 10 per cent has climbed 3 per cent per year, also one the fastest rates in the OECD.

But the compounding effect of the different rates has opened up a very wide income gap. A family taking home $30,000 in the mid-1980s would be earning $68,000 today if income had grown 3 per cent per year. A family earning $30,000 enjoying a 4.5 per cent rate of growth would be earning $103,000 today.

Entitled Divided We Stand, the report is unable to identify any one single cause of growing income inequality in English speaking nations, saying it could flow from increased global competition for highly skilled workers, advances in information technology making highly skilled workers more prized, or those workers are putting in more hours.

http://www.smh.com.au/business/top-earners-taking-bigger-slice-of-the-pie-20111205-1ofhm.html

let the good times roll .....

Australia's top 1 per cent of earners now take twice as big a slice of national income as they did three decades ago, new research on the widening gap between the nation's rich and poor shows.

And the share raked in by the super rich - the top 0.1 per cent of earners - has grown even more rapidly, increasing almost fourfold since 1981.

The research, by federal MP and economist Andrew Leigh, also found that while the salaries of business chiefs have soared, politicians and senior public servants are paid much less now, relative to the average wage, than they were early last century.

Dr Leigh said Australia's top 1 per cent of earners had 4.6 per cent of the nation's income in 1981, but that share rose to 10.1 per cent in 2006 before dropping slightly to 8.6per cent in 2008.

Australia reduced income inequality from the 1950s to the early 1980s, but the gap between rich and poor had since widened, he said. Since 1981 the super-rich's share of national income had risen almost fourfold to a high of 3.65 per cent in 2006. Dr Leigh's research shows also that, while politicians and top-level bureaucrats regularly cop flak over perceptions they are overpaid, their salaries are closer to the average Australian now than they were for most of last century.

A federal MP received $800 a year in 1901, 5.3 times the then average worker's pay of $151. But in 2009, an MP's salary of $136,510 was just 2.8 times the average wage.

And while deputy secretaries in the public service earned almost five times the average Australian wage in 2007, their equivalents back in 1926 earned more than 10 times the average salary.

Dr Leigh, the Labor Member for Fraser, told The Canberra Times yesterday that while almost everyone's income had risen, ''it isn't always the case that those increases are distributed across the board''.

''I think the gap between rich and poor matters a lot. Too much inequality risks splitting us into two Australias and a society that I would be less comfortable living in than an egalitarian Australia.''

Australia was a long way off being as unequal as the United States.

''We have a top 1 per cent with about 10 per cent of national income, and in America it's about 20 per cent,'' Dr Leigh said. ''So we don't yet have American-style levels of inequality, but it's important to have a national discussion about income distribution.''

One of Australia's largest unions, United Voice, said yesterday the widening income gap also hurt pensioners, as most benefits were tied to average incomes.

The union's ACT spokeswoman, Yvette Berry, said, ''If most incomes stay low, the pension stays low, too. And we see many people who depend on the pension or part-pension ending up in poverty when they retire.''

Ms Berry, whose union represents mostly low-income workers, said it was important that governments and employers created better quality jobs that gave staff useful skills.

''When the income gap widens, it decreases people's ability to find better jobs. Instead of having one good job, they get stuck needing to work two or three shit jobs.''

Meanwhile, the federal Remuneration Tribunal is expected to reveal within a fortnight its recommended changes to the way politicians are paid. The tribunal is reportedly considering boosting MPs and ministers' base salaries by $40,000 to $90,000, and cutting their allowances.

Dr Leigh said yesterday it was appropriate that an independent body set parliamentarians' pay, saying problems occurred when politicians were involved.

http://www.canberratimes.com.au/news/national/national/general/rich-keep-getting-richer/2392165.aspx?storypage=0