Search

Recent comments

- stenography.....

1 hour 53 min ago - black....

1 hour 51 min ago - concessions.....

2 hours 53 min ago - starmerring....

6 hours 58 min ago - unreal estates....

10 hours 44 min ago - nuke tests....

10 hours 48 min ago - negotiations....

10 hours 51 min ago - struth....

1 day 35 min ago - earth....

1 day 1 hour ago - sordid....

1 day 1 hour ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

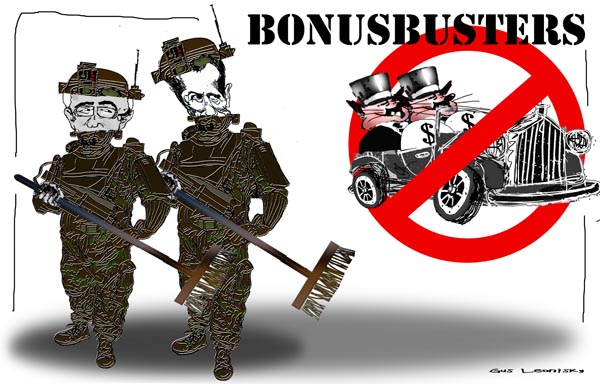

bonusbusters

Alistair Darling is set to ask bankers to crack down immediately on bonuses in a key speech to Labour's conference.

The chancellor is to bring in new laws in the autumn but will say to bankers that there is no need to wait for legislation and they should act now.

Labour is using its week in Brighton to launch a fight back against the Tories, claiming it is now the "underdog".

But there was controversy on the first day as the prime minister was quizzed on his health on the BBC's Marr show.

Mr Darling is to tell the conference in Brighton that he is acting together with French Finance Minister Christine Lagarde and is hopeful that countries around the world will push the guidelines agreed at last week's G20 conference in Pittsburgh.

He will say: "Within months, the country faces a big choice. A choice not just about who's in government but about values that will shape our country and the opportunities for our people. A choice that will affect every area of our lives, every aspect of our future.

"Let me assure the country - and warn the banks - that there will be no return to the business as usual for them.

-----------------------

Ah ah...

- By Gus Leonisky at 28 Sep 2009 - 6:40pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

wriggling bonuses...

From Timesonline

Bankers wondering how large their annual bonuses are going to be this year will be none the wiser after listening to the fine words coming out of the G20 in Pittsburgh.

The Financial Stability Board (FSB), the panel of central bankers and regulators advising ministers on the shape of the new post-crunch financial world, proposes lots of laudable ways that bank pay can be reformed to discourage recklessness. But there is plenty of wriggle room left for regulators in individual countries on interpretation of the guidelines, and even more wriggle room on how individual banks then choose to abide by them.

'swannee .....

from Crikey .....

Swan ringing hollow on executive pay

Adam Schwab writes:

Treasurer Wayne Swan and Prime Minister Kevin Rudd certainly know how to make the right noises about excessive executive pay. Speaking at the G20 Summit over the weekend, Swan supported moves to curb executive largesse and noted that "we need to have action in this area, the public are sick and tired of some of these obscene packages".

However, when it comes to actually doing something about executive pay, the federal government prefers talk and reviews over action. Witness the useless draft APRA report released recently, which does nothing to address the ever-increasing quantum of remuneration. Similarly, the Productivity Commission report, penned by Alan Fels, is expected to be released in draft form this week is also likely to talk tough, but provide little real means for an actual curb of executive pay.

If there were ever going to be a slowdown in monies paid to corporate bosses, it would presumably occur in a year where share prices slumped -- much like last year. Despite a recent recovery, the Australian market is still 30% below its 2007 peak.

However, perversely, a recent survey by Mercer has indicated that short-term bonus payments for executives of ASX-listed companies actually rose by 14% during 2008 -- executives also witnessed their base-pay jump by 5.7%. Wealthy executives must chuckle at the claims of alignment between shareholders returns and remuneration -- such alignment appears to involve paying a lot more to executives during the good times and paying a little more to executives during the bad times.

The non-binding remuneration report, while slightly embarrassing to directors, appears to be having little or no effect on their behaviour.

In 2008, Wesfarmers' shareholders roundly rejected the company's remuneration policies -- this year, the board responded by giving struggling CEO Richard Goyder a base pay rise to $2.97 million and a short-term cash bonus of $1.1 million (up from zero the previous year). Goyder's total remuneration increased by more than 60% to $8.1 million. Not only did Wesfarmers appear to completely ignore its shareholders' views, the company also adopted little commercial sense. In the past two years, Wesfarmers return on equity (a key indicator of management performance) has dropped from 25.1% to 7.4% last year -- largely due to Goyder's terribly timed acquisition of Coles Group.

Despite the contradiction, Wesfarmers chairman (and also chair of the company's remuneration committee) Bob Every told the Australian Financial Review that there was no need for more regulation of executive pay and that "boards react to that and are adjusting. Australia has not seen the excesses of other parts of the world and so I personally think the system works quite well." Others may disagree with Every's views -- especially Wesfarmers shareholders who have witnessed the value of their holdings sliced in half largely due to Wesfarmers' well-remunerated management.

Wesfarmers is far from alone in disregarding the views of its shareholders. Last year, Qantas received a 40% rebuke from shareholders regarding pay practices, but clearly failed to take the advice on board. This year, despite only working for five months, former CEO Geoff Dixon collected $10.7 million -- including a termination payment, despite his departure being voluntary.

Similarly, last year, Asciano was only able to avoid a complete shareholder revolt after CEO Mark Rowsthorn voluntarily agreed to take a $750,000 bonus drop in 2009. Despite Asciano reporting a $244 million loss, and being forced to undertake a massively dilatory share offer at $1.10 per share (after rejecting a $4.40 per share offer months earlier), Rowsthorn saw his cash bonus ostensibly increase this year. Asciano shareholders must shudder at the thought of how much Rowsthorn would be paid should his performance be anything other than poor.

Given the vote on Remuneration Reports appears to be having little or no effect on remuneration, it is hard to envisage fuzzy proposals such as those purported by APRA will do anything other than let politicians temporarily off the hook.

There is a simple was to curb much of the executive pay problems -- that is, by actively reducing the agency costs that cause the problem. The main reason executives are paid so much is because the people who determine executive pay (company directors, specifically the chairman and members of the Remuneration Committee) have no personal interest in minimising executive pay. It is shareholders who pay the bills, not the directors. (If anything, the opposite is true -- cutting a CEO's pay would make five-course boardroom lunches just unbearable).

To fix the problem, the legislature needs to ensure that directors are personally accountable -- to achieve this, should shareholders reject a company's remuneration report, the chairman and members of the Remuneration Committee should forgo all directors' fees for the previous year (or be forced to repay any fees already made), Plus, they should all be required to stand for re-election to the board the following year to allow shareholders to vote them out of office. This will ensure that directors are held personally accountable for their actions, rather than suffer some minor embarrassment when a remuneration report is rejected.

When a director has their own livelihood at stake (and directors' fees are often upwards of $200,000 annually), one suspects they will suddenly have a greater empathy for long-suffering shareholders.

Meanwhile back in the swamp

Meanwhile back in the swamp of the scam market in January this year...

From Komisar

The New York Fed under Geithner’s presidency has failed to stop massive naked short selling of U.S. Treasury bonds that threatens the stability of the market and sale of the bonds.

Ironically, the scam, enabled by a lack of regulation at the behest of Wall Street brokerage houses, makes it more expensive for the U.S. to bail out those same financial institutions.

It happens this way: an individual or fund is allowed to sell bonds without owning them. This is called short selling. The seller, whose broker has generally “borrowed” bonds from another broker, is supposed to subsequently buy them on the market, and return them to the lender. The seller does this because he believes that the bond is going down, and he will buy them at a cheaper price than he sold them for.

Naked short selling occurs when a seller does not borrow the bonds for delivery at settlement, and therefore never has to buy them. This is called a failure to deliver, or FTD.

Meanwhile, the buyer thinks he or she has the bonds but has just an IOU. The result is a distortion of the market. Sellers sell bonds they never own or borrow, so there are more securities sold than issued by the government. These phantom bonds don’t represent money paid to the U.S. Treasury or genuine securities for buyers.

The major broker-dealers who handle bond trades like the system. They profit from fails by using clients’ money for other purposes.

The economist who has done the key work on this issue is Dr. Susanne Trimbath, who heads STP Advisory Services in Omaha. She previously worked for the Depository Trust Co, a subsidiary of Depository Trust and Clearing Corp, the U.S. clearing house for stocks and bonds.

Dr. Trimbath said, “In fall of 2008, about two trillion dollars in Treasury bonds were sold but undelivered for six weeks, more than 20 percent of the daily trading volume, up from 8.6 percent in the first five months of 2008.” It was a spike from 1.2 percent in the first five months of 2007.

“There was excess demand for the Treasuries,” she said. “Rather than allow this to push the price up, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and the DTCC allowed failures to deliver to depress the price.” This affects the value of bonds held by individuals, funds and major investors such as China.

The latest figures on failures to deliver are 600-800 billion dollars. Dr. Trimbath said, “The numbers look better now because the Fed threw two trillion at the market, which was used to cover these fails.”

--------------------

So this is why I'm poor, trying to live from cheaply flogging a few honest goods, while other bums are selling things they don't have — a bit like selling your neighbor's furniture, without him knowing that while he was asleep his bed was sold ten times over, over which 5 people made huge profits, 3 people made massive losses and 2 collected fees for selling his bed which he still owns, sort of because he bought it on credit anyway — the repayments of which have gone an extra 5 per cent in the red to pay for the short fall on the scam market.