Search

Recent comments

- not worth...

52 min 37 sec ago - illegal stuff....

1 hour 42 min ago - no shipping.....

11 hours 30 min ago - digging graves....

11 hours 42 min ago - BS draft...

11 hours 50 min ago - tankers ablaze....

12 hours 37 min ago - shoes....

14 hours 35 min ago - new map....

15 hours 9 min ago - weapongeddon....

15 hours 26 min ago - squirming....

15 hours 42 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

cutomer focus .....

AFR defends the indefensible on bank fees

Adam Schwab writes:

Australia's leading banking journalist, the Financial Review's Andrew Cornell, undertook a valiant, albeit flawed defence of banking exception fees yesterday.

Cornell claimed that exception fees (which last year totalled almost $1.2 billion) were "necessary and the consumer advice groups and politicians such as (Family First's) Steve Fielding would actually serve consumers better by giving them the material to manage their banking better."

The Reserve Bank last week broke down the types of penalty fees charged by banks to Australian consumers. The fees included $415 million relating to credit cards (usually, for late repayments) and $490 million for breaching terms and conditions of deposit accounts.

Despite every Australian paying on average, more than $50 last year to banks for penalty fees, Cornell felt that such fees were actually a good thing for consumers, noting:

To charge for exceeded credit limits, non-payments or use of a rival's infrastructure is actually in the interest of the general consumer because without such disincentives, those who do not contravene their banking arrangements cross-subsidise those who do, for whatever reason. Without them, all prices would be higher.

Cornell's arguments may hold a small degree of accuracy if the banks operated in a vaguely free market in which consumers had real choice in banking services. That is however, not the case. The vast majority of exception fees charged by banks would most likely be deemed illegal under common law on the basis that they do not represent an accurate reflection of the cost to the bank and the bargaining power between the parties is grossly unbalanced.

This is evidenced by the banks merely debiting penalty fees from a client's account at its own discretion (some banking contracts even allow for financial institutions to charge whatever fees they see fit). This writer successfully sought and obtained a declaration from the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal that so-called exception fees were unenforceable penalties and not permissible under common law principles.

In some cases, banks will charge customers of "over-limit" charge on a credit card (of upwards of $40) for exceeding their credit limit, by even $1. The customer is often unaware of the balance remaining and the transaction may often be an innocent mistake (further, most customers would rather not exceed their limit anyway, but rather, be told that they are over-limit and pay by some other method). When such an event occurs, Australian banks will charge a penalty fee which is in no way commensurate with the cost incurred by them as a result of the breach.

Similarly, banks will charge exception fees of more than $40 for a "late repayment". The cost of those breaches to the bank has been estimated to be at far less than $1. Not only does the bank earn a windfall profit from the exception fee, but they are also able to collect interest charges of approximately 20 percent.

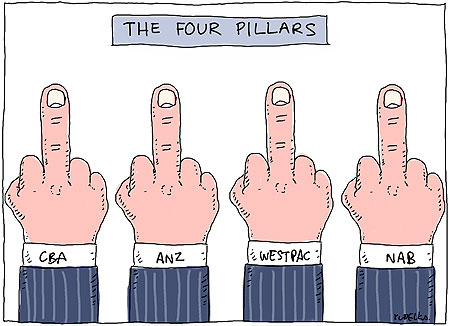

Despite Cornell's contentions, bank penalty fees do not cross subsidise "good customers", but rather, simply add to the Big Four's bottom line. The bank fees were not in existence a decade ago, but rather materialized when banks realized they could charge such fees with virtual impunity. Banks use their oligopolistic power and legal expertise to enforce these likely illegal (and certainly immoral) fees on their largely unsophisticated customer base.

The increased profitability (helped largely by the billions being reaped from exception fees) has led to banking executives being among the highest paid workers in Australia. In 2008, CBA chief, Ralph Norris took home $8.6 million, Westpac CEO Gail Kelly earned $8.5 million while ANZ head, Mike Smith, earned $12.9 million last year (including a $9 million sign-on bonus). It appears that Cornell got it wrong - exception fees do not benefit "good customers", but rather, line the pockets of bank executives.

Cornell also claimed that "Fielding's stupidity, unfortunately, is repeated even by some in the financial media, who should at least have some idea and ability to comprehend the industry the report on. For a start, the price 'charged' for a service is not automatically a 'gouge' -- sometimes it is the price."

Sorry Andrew, but charging what is most likely illegal fees to unsophisticated consumers is not only a gouge, but a blatant misuse of market power in an industry already substantially subsidised by taxpayers through a deposit and wholesale funding guarantee.

There are few easier jobs then being a banking executive, especially when you have friends like the Financial Review.

- By John Richardson at 26 May 2009 - 4:05pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

bandido .....

from Crikey .....

ANZ CEO speaks

Adam Schwab writes:

When one operates an illicit or somewhat immoral business they are usually well advised that publicity is not their friend. The mob, narcotics dealers or moonshine liquor sellers are well aware of this fact, preferring to conduct their business quietly, avoiding public comments. One would think therefore that the millionaire CEO of an institution whose earnings are underpinned by taxpayer backing and legally dubious penalty fees would be advised to avoid debates such as those concerning executive pay.

Alas, ANZ's bombastic chief, Mike Smith, is not concerned about appearances, criticizing recent "bank bashing" and "irrational and uninformed debates" regarding executive remuneration. Smith last week made the keen observation that "when you compare salaries to the US or to Europe, Australia is actually well positioned."

Perhaps Smith was speaking from the point of view of an executive who was last year paid almost $13 million to run a bank whose share price slumped by almost 50% since October 2007, rather than the point of view of shareholders. In fact, Australian banking executives have, in recent times, been very well paid, even compared to their trans-Pacific rivals.

Recipients of TARP monies in the United States have had limitations placed on their remuneration. Further, Goldman Sachs head, Lloyd Blankfein and six other top Goldman executives agreed to forgo their bonuses for 2009, JP Morgan boss, John Mack gave up his bonus for the second year straight while Merrill Lynch executives also agreed to forgo 2008 bonuses. Despite ANZ (and its fellow oligoploists) benefiting from a taxpayer guarantees on deposits and wholesale funding, neither Smith, nor any executive appear to have discussed substantially reducing their remuneration this year or forgoing bonuses.

Smith himself received a $9 million "sign-on" bonus when he joined ANZ from HSBC in October 2007. The money was paid to compensate Smith for salary he would have received at HSBC. Exactly why the ANZ board weren't able to locate an executive who didn't require a $9 million dowry is unclear. Of course, when it comes to selecting executives, the ANZ board has not exactly covered itself in glory.

ANZ's immediate past CEO, John McFarlane, was paid more than $26 million during his last four years as ANZ head, but conceded he had never heard of Opes Prime. ANZ's exposure to Opes margin lending business is likely to cost is several hundred million dollars and tarnished the bank's already shaky reputation. During McFarlane's reign ANZ also accumulated a $500 million (unsecured) exposure to Centro, a $150 million exposure to collapsed US lender Countrywide and a $226 million exposure to monoline insurer, ACA Capital (as well as exposures to Hedley Lesiure, Pubboy and Tricom). Fortunately for McFarlane, ANZ's woeful performance did not prevent him from receiving 95 percent of his potential short-term bonus in 2007 (totaling $2.09 million).

Smith did not only defend executive largesse, also taking aim at those spoilsports who dared criticise the competition, or lack thereof, in Australia's financial sector. Smith stated last week that "this whole issue of 'are banks being competitive' is crazy. People have a choice." Perhaps Smith was referring to the choice between the various big four banks who all failed to pass on the Reserve Bank's most recent interest rate cut in full. Or maybe Smith was speaking of the competition between the big four whom appear to be competing as to which can charge customers the highest level of penalty fees, despite their apparent illegality under basic common law principles.

Smith did note however, that 'in his experience', bank competition is strong. He is probably right in a sense -- banks are fairly competitive about obtaining clients who earn upwards of $10 million a year. It is usually those pesky pensioners, single mothers and the unemployed who tend to find things a bit more difficult dealing with the allegedly competitive banking sector.