Search

Recent comments

- crummy....

13 hours 16 min ago - RC into A....

15 hours 8 min ago - destabilising....

16 hours 12 min ago - lowe blow....

16 hours 44 min ago - names....

17 hours 21 min ago - sad sy....

17 hours 46 min ago - terrible pollies....

17 hours 56 min ago - illegal....

19 hours 8 min ago - sinister....

21 hours 30 min ago - war council.....

1 day 7 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

nonetheless, africa will bloom, next....

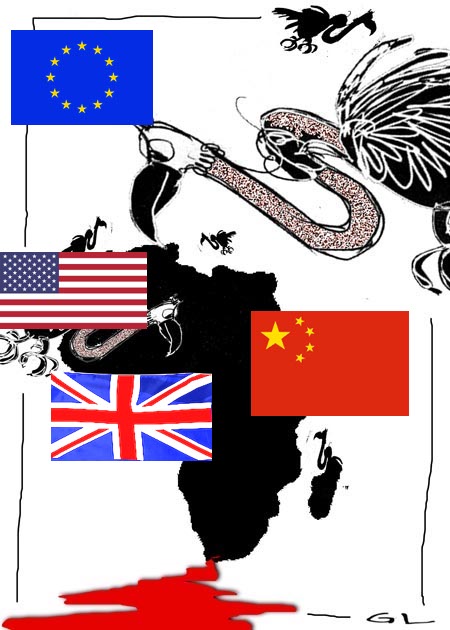

Africa suffers… In many places of Africa, the people suffer… The pains come from various sources:

— the lingering momentum of COLONIALISM…

— the Vulture funds that are bleeding countries by refinancing the IMF and World Bank bad debts…

— Western induced POVERTY through deliberate bad debts...

— the Muslim terrorists being mostly funded by the USA and the Wahhabis/Sunnis of Saudi Arabia…

— Slavery (historical and present)….

— plunder of resources by Multinationals…

— inherited and Western cultivated corruption in order to prevent increase in the standards of living and to maintain divisions….

— Murders of many African thinkers and independent inspiring leaders….

— Tribalism, broken by artificial boundaries….

— Racism…

— Global warming which is increasing desertification….

— Diseases (imported and intrinsic)....

— Useless aid, targeted to kill local manufacturing and farming...

…

And possibly the least of the problems:

— the Belt and Road infrastructures funded by loans from China… Loans that have to be repaid…

But, in some way — the Belt and Road infrastructures HAVE BEEN NEEDED for further developments.

Yet, due to the lack of local social structures and efficient governmental institutions, the Belt and Road builds are not profitable, yet…

Apparently, these Chinese projects also suffered from the way they have been efficiently implemented… financially and technologically.

According to one source, Dr Keyu Jin, the financial side of these operations is based on the Chinese Mayor incentive schemes which cannot be transcribed into African aspirations. The technological side also lacked the teaching of locals in the Chinese construction methods. Say Chinese workers and engineers came in and left without much social interactions with the locals. Projects are delivered on time and on budget, but lacked the local incentive and management to be profitable.

Gus’s personal view is that eventually, should the West not try to sabotage the Chinese and African efforts, the local Africans will come to turn these projects into useful development away from colonialism and towards a self-sufficient happy and peaceful lifestyle — despite the cost of repayment — a cost which China can delay until a new painless deal is reached if needed…

At this level, many African nations are demanding reparations for the trauma of colonialism and slavery to the tune of more than $100 trillion… YES, $100/150 TRILLION… Well managed, such sums (or part thereof IF ever paid), could help pay the Chinese loans and settle vulture debt instantly, plus provide a capital to invest in social structures such as education, say schools and universities, more efficient governmental management, and reducing corruption, while promoting an African Ideal… One can see some interesting moves already…

Meanwhile, there are still many avenues in which China and Africa desire to cooperate to improve the life of Africans.

As well, the UNITED NATIONS should provide a better platform for self-determination, something that TRUMP’s Board of Peace will try to kill off… in order to carry on with the plunder…

So here are a few views. the future of Africa as a whole is fluid, probably exciting and sustainable, though geezers like Trump and Macron have been hindering proper development on all fronts, and may want to continue under false pretences of "helping"...…

Gus Leonisky

Working in Africa during the 1960s

=========================

China and Africa have reaffirmed their shared belief that mutual learning between civilizations remains a vital source of development and solidarity, releasing a list of 58 key activities for the 2026 China-Africa Year of People-to-People Exchanges.

While addressing the opening ceremony, held on Thursday at the headquarters of the African Union in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Foreign Minister Wang Yi emphasized that people-to-people exchanges constitute the most solid foundation of China-Africa friendship.

China-Africa cultural and social exchanges have already yielded tangible results. China has established 17 Luban Workshops across 15 African countries, training tens of thousands of skilled professionals. It has also signed tourism cooperation agreements with more than 30 African countries, with 34 African destinations now open to Chinese group tours.

Against a backdrop of mounting global turbulence, Wang said that China and Africa have an even greater need to uphold fairness and justice, strengthen solidarity, and deepen exchanges and cooperation.

Wang expressed China's readiness to expand unilateral opening-up toward Africa, turning its vast market into new opportunities for African countries. He also called for deeper mutual learning through enhanced exchanges on governance and modernization experiences.

African leaders at the ceremony expressed confidence that the year of people-to-people exchanges would usher in a new chapter in Africa-China relations, pledging to expand cooperation in culture, education, tourism, the arts and youth exchanges.

Nearly 600 people-to-people exchange activities will be held throughout the year under the theme Consolidate All-Weather Friendship, Pursue a Shared Dream of Modernization, Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Mao Ning said at a news briefing on Friday.

On Thursday, Wang also held the ninth China-AU Strategic Dialogue with AU Commission Chairperson Mahmoud Ali Youssouf at the AU headquarters.

Wang is currently on a six-day visit to Ethiopia, Somalia, Tanzania and Lesotho, marking the 36th consecutive year that Africa has been the destination for Chinese foreign ministers' first overseas trip of the year.

During the dialogue, Wang said the long-standing diplomatic tradition reflects both the continuity of China-Africa friendship and the stability of China's Africa policy, and demonstrates solidarity among developing countries.

Zhou Yuyuan, deputy director of the Center for West Asian and African Studies at the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies, said putting people first is both the starting point and ultimate goal of China-Africa cooperation.

As the world's youngest continent, Africa's demographic potential can be unlocked by empowering youth and women and broader segments of society.

China will continue to inject stability and certainty into Sino-African cooperation and global engagement with Africa, giving the partnership growing significance in contrast to hegemonic and self-serving approaches, Zhou added.

https://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202601/10/WS696189d3a310d6866eb32fde.html

=====================

Africa has articulated a clear and compelling vision for its representation on the Security Council, that body heard today at a historic high-level debate on enhancing the continent’s effective participation in the United Nations organ tasked with maintenance of peace and security.

The meeting was convened by Sierra Leone, Council President for August, and chaired by that country’s President, Julius Maada Bio. Speaking in his national capacity, he said: “Today, I speak as a representative of a continent that has long been underrepresented in the decision-making process that shapes our world.” Setting out the aspirations of its fifty-plus countries and over 1 billion people, he stated: “Africa demands two permanent seats in the UN Security Council and two additional non-permanent seats, bringing the total number of non-permanent seats to five.” The African Union will choose the continent’s permanent members, he said, stressing that “Africa wants the veto abolished; however, if UN Member States wish to retain the veto, it must extend it to all new permanent members as a matter of justice.”

This is the Common African Position, as espoused in the Ezulwini Consensus and the Sirte Declaration, he said. As the Coordinator of the African Union’s Committee of Ten, his country has spearheaded efforts to amplify the continent’s voice on the question of its representation. Noting the bloc’s admission to the Group of Twenty (G20) as a welcome development, he said it is absurd for the UN to enter the eightieth decade of its existence without representation for his continent. It must be treated as a special case and prioritized in the Council reform process, he stressed.

Highlighting the way slavery, imperialism and colonialism have shaped current global power structures, he noted the persistent stereotype of Africa “as a passive actor” in global affairs. The continent’s inclusion in the permanent membership category will ensure that decisions affecting it are made with direct and meaningful input from those most impacted. This will not only unlock Africa's full potential; it will also improve the Council’ legitimacy, he added.

“The cracks” in the Organization’s foundation “are becoming too large to ignore”, António Guterres, Secretary-General of the United Nations acknowledged during his briefing. The Council was “designed by the victors of the Second World War and reflects the power structures at that time,” he said, recalling that in 1945, most of today's African countries were still under colonial rule and had no voice in international affairs. As a result, there is no permanent member representing Africa in the Council and the number of elected members from the continent is not in proportion to its importance.

It is unacceptable, he underscored, that “the world's pre-eminent peace and security body lacks a permanent voice for a continent of well over a billion people”, whose countries make up 28 per cent of the membership of the UN. While Africa is underrepresented in global governance structures, it is overrepresented in the challenges these structures address. Nearly half of all country-specific or regional conflicts on the Council's agenda concern Africa, and “they are often exacerbated by greed for Africa’s resources” and further aggravated by external interference, he said.

“Reform of this Council membership must be accompanied by a democratization of its working methods,” he added, drawing attention to the need for more systematic consultations with host States and regional organizations. Enhancing Africa’s representation in the Council is not just a question of ethics; “it is also a strategic imperative that can increase global acceptance of the Council’s decisions,” he reminded that body.

Echoing that, Dennis Francis (Trinidad and Tobago), President of the General Assembly, said: “We cannot continue to take [the United Nations’] relevance for granted.” Instead, he added, “we must earn it, daily, with the actions we take”, including meaningful reform. Highlighting the Assembly’s active engagement on Council reform, he said the current draft of its input to the Pact of the Future calls for redressing the historical injustice to Africa.

The continent, he pointed out, is home to 54 of the UN’s 193 members, accounts for 1.3 billion of the world’s population and hosts the majority of UN peacekeeping operations. “The fact that Africa continues to be manifestly underrepresented on the Security Council is simply wrong,” he said. Alongside the growing calls for a Council that is more representative and transparent, he noted, there are also calls for a revitalized General Assembly. Member States are asking that body to assume a greater role in peace and security matters but also hold the Council more accountable for its actions — “and, indeed, inaction” he said.

The United Nations is clearly suffering from a legitimacy crisis, Sithembile Mbete, Senior Lecturer of Political Sciences at the Faculty of Humanities, University of Pretoria noted, adding that younger generations are witnessing its failures in “real time” on social media platforms. She described Africa’s experience of the UN system over the past 80 years as one of “misrepresentation and underrepresentation”. This has become evident in the perpetuated narratives of Africa as a continent of “backwards societies” reliant on aid as well as in the continent’s exclusion from permanent membership of the Council and inadequate representation among non-permanent members.

Detailing the historical context for this, she recalled the four centuries of European slave trade starting in 1450 and devastating Africa’s population, culture, and economies, as well as the 1884 Berlin Conference that imposed colonial States, which still impacts the continent’s economic relations with rich nations. In the 30 years since the end of the cold war, African subjects took up nearly 50 per cent of the Council’s meetings — but while Africa was on the menu, as was the case in Berlin 100 years ago, it still does not have a permanent seat at the table. By 2045, Africa will have 2.3 billion people, making up 25 per cent of the global population, she said, asking diplomats to summon “the courage” to confront the power relations that are preventing meaningful reform.

Lounes Magramane, Secretary-General of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and National Community Abroad of Algeria, pointed to the hotspots on his continent, from the security, development and humanitarian challenges in the Sahel region to the Sahrawi people’s struggle for their right to self-determination. Yet, Africa is the only group not represented in the permanent category, he said, reiterating the call for allocation of two permanent and two non-permanent seats. Permanent members must commit to support the reform process, he said, calling on them to participate constructively in the intergovernmental negotiations.

China’s representative was one of several speakers who traced the connection between colonialism and Africa’s under-representation. The brutal legacy of Western colonial rule, the inhumane slave trade and resource-plundering impoverished the people of that continent and artificially interrupted their development. This is the root cause of all historical injustices in Africa, he asserted. “Some Western countries still cling to the colonial mindset,” he said, interfering in Africa’s internal affairs using financial, legal, and even military means to exert their influence in currency, energy, minerals and national defence. He urged those countries “to change course and return the future of Africa to the hands of the African people”.

Eight decades ago when the Council first met, the United States’ delegate said, “its architects could not have imagined then what the world would look like today, as we cannot imagine what it will look like 70 years from now”. In 2050, one in four people on the planet will be African, she noted, adding that Africa has the fastest-growing population of any continent. “We all benefit when African leaders are at the table,” she said, adding that the upcoming Summit of the Future should be a platform for meaningful progress. At the same time, “Africa’s problems are not Africa’s alone to deal with,” she said, as she warned against the attempts of some States to obstruct Panels of Experts. They represent a critical UN tool that provides the body with credible information about security threats, she added.

General Jeje Odongo Abubakhar, Minister for Foreign Affairs of Uganda, said that despite being “the market of the world” and a leading contributor to UN peacekeeping operations, Africa has been “unjustly excluded from positions of power and influence” in the Council. A stronger presence will give the continent a “much-needed platform for engagement with the international community as an equal and significant partner,” he said. Voicing support for the intergovernmental negotiating process, he noted that “it is taking too long to conclude”.

Mozambique’s delegate noted that this topic has been long addressed in many different fora, including the negotiations on Assembly resolution 62/557 concerning “Question of equitable representation on and increase in the membership of the Security Council and related matters”. Yet, regrettably, “the Security Council’s engagement in that process has been modest to say the least,” he said, adding that the body’s position has not changed much since the 1965 expansion that added the four elected members to the organ. To those who argue that expanding membership will diminish the Council’s efficacy, he pointed out that legitimacy and efficacy are interlinked and mutually reinforcing.

Shinsuke Shimizu, Ambassador for International Economic Affairs in Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, commended the continent’s effort to shoulder more responsibilities at the Council, highlighting the landmark resolution on financing of African Union-led Peace Support Operations. The Council must be reformed with an expansion in both permanent and non-permanent membership, he asserted. Also supporting the expansion of both categories of membership was Lord Collins of Highbury, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office for the United Kingdom. In order for the Council to be as effective as it can be, it must urgently include permanent African representation, he said.

The representative of France stressed the need to strengthen the Council’s legitimacy whilst preserving its decision-making ability. The reform is “possible”, and Africa should serve as the “catalyst” for this change, she said, adding that the ambitious goal of expansion must be included in the text of the Pact of the Future. She also urged Member States to join her country’s initiative to limit the use of the veto in cases of mass atrocities.

The Council also heard from several members of the African Union’s Committee of Ten Heads of State and Government, also known as C-10, which was established in 2016. The speaker for Equatorial Guinea noted that the Common African Position has received much support from Member States in the Assembly as well as the five permanent Council members, “but we have not seen such support become a concrete reality and lead to actual reforms.” He invited them to clearly define that support and take action. Congo’s delegate said that given the five permanent Council members’ recognition of the historic injustice done to Africa, there is a real opportunity to advance this reform, encouraging Member States to consider seriously the proposals in the Common African Position.

The representative of Kenya said the “marginalization is getting worse as the powerful countries seek after their own interests” while Namibia’s delegate, who recalled the Council’s lack of support for his country during its struggle against apartheid and colonialism, underscored that enhancing Africa’s representation is “not a favor to the African continent”. The continent’s patience should not be mistaken as acquiescence, he warned. The representative of Senegal rejected “interim solutions that relegate new members to second-class roles” adding that “permanence is not a matter of privilege; it is a question of representativeness”.

While speakers expressed broad support for reforming the Council’s membership, some voiced reservations about certain aspects of the proposed reforms.

The representative of Italy, speaking for Uniting for Consensus, which he described as a reform group dedicated to achieving a more democratic Council, suggested increasing the number of seats in a reformed Council to a maximum of 27, out of which Africa would obtain 6 seats, thereby “becoming the group with the largest number of elected seats”. Intergovernmental negotiations have shown increasing convergence on the expansion of non-permanent seats based on equitable geographical distribution, he observed. At the same time, Africa’s aspiration to serve for longer periods on the Council is legitimate, he said, noting his group has proposed longer-term re-electable non-permanent seats to provide continuity of tenure. This will maintain a system of democratic accountability “without creating additional and unjustifiable privileged positions”, he said.

Along similar lines, the representative of the Republic of Korea, who reaffirmed his country’s support for Council reform, “standing shoulder-to-shoulder with Africa”, also cautioned that increasing permanent membership will mean that the vast majority of the UN membership would inevitably be further marginalized. “The Republic of Korea’s consistent and strong reservations about expanding the permanent membership are thus based on the rational and logical conclusion that this antiquity needs to be contained, not proliferated,” he underscored. The immediate priority should be expanding the non-permanent membership, he said, adding that “any fixed composition of new permanent members will serve at best as a still picture or a snapshot of one moment of history”.

Guyana’s delegate rejected the proposal for expanded permanent membership without the veto privilege, cautioning that this will create hierarchies of members in the permanent category. Moreover, it will perpetuate injustice by restricting the prerogatives of new permanent members, including from Africa. While firmly supporting the abolition of the veto, she contended that “as long as it continues to exist, all new permanent members should have the prerogative of its use”. Notwithstanding, the use of the veto must be curtailed, she stressed, adding that it should never be used to paralyze the Council in cases of mass atrocities such as genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity.

The representative of Pakistan said the veto is the principal reason for the Council’s frequent inability to take effective collective action. “The problem cannot be the solution,” he said, opposing the addition of new permanent members on the Council as demanded by four individual States, viewing it as a move to promote narrow national interests. Advocating for a “regional approach”, he expressed support for “special regional seats” to be occupied by States selected by the region and elected by the General Assembly. Similarly, the concept of longer-term and re-electable seats within each region — proposed by the Uniting for Consensus Group — can be considered as a way to achieve these objectives. While the veto cannot be abolished, it must be severely constrained, particularly in the case of the genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity, he said.

The representative of the Russian Federation, however, expressed support for retaining the mechanism of veto, which ensures the adoption of realistic decisions. Describing his country as a “consistent supporter” of Security Council reform, he cautioned, however, against creating a Council that is “too broad” to maintain its “effectiveness and authority”. He also pointed to the need for the redistribution of “penholderships” which are currently dominated by former colonial Powers in the Council. All efforts to correct this situation are “sabotaged by Western countries”, he said, adding that “they are more concerned with ensuring that their NATO [North Atlantic Treaty Organization] bloc allies are included in the permanent pool of the Council alongside countries from the Global South.

https://press.un.org/en/2024/sc15788.doc.htm?ysclid=ml1b1cbazl42613071

=======================

Over $130 trillion looted: The economic case for African reparations

Estimates suggest that if Africa had retained even a fraction of the wealth extracted during slavery and colonialism, the continent’s economic trajectory would be unrecognisable today.

Tens of trillions of dollars lost, generations disrupted and denied futures. These are not metaphors, they are balance-sheet realities.

“Europe and the West would not be wealthy today without slavery and colonial rule. Because, the greatest wealth was present in the territories of what is now Mali, Ghana, and ancient Egypt of which each, was brutality taken as slaves to work for hundreds of years under very inhumane circumstances by the west,” began Ambassador Jesús Alberto GARCÍA.

Ghana travel guide

Newly published preliminary findings by the Pan-African Progressive Front identify four core categories of damage from slavery to colonial rule — and their continued impact on the Continent. The study argues that these categories can constitute the foundation of any credible legal or political claim against the erstwhile colonial powers.

https://citinewsroom.com/2025/12/over-130-trillion-looted-the-economic-case-for-african-reparations/

==================

The New China Playbook: Beyond Socialism and Capitalism

by Keyu Jin.

Swift Press, 360 pp., £25, July 2023

The Mayor Economy

Nathan Sperber

During the Covid lockdowns of 2020, an influx of central bank injections into Western capital markets sent stock indices soaring. A few listed companies became social media favourites, leading to frenzied buying on the part of mostly young, mostly male amateur investors, stuck at home trading equities on mobile apps such as Robinhood. These hyped-up stocks – ranging from GameStop to Tesla – became known as ‘meme stocks’ and this episode as the ‘meme stock craze’. A Chinese electric vehicle start-up called Nio, which had listed on the New York Stock Exchange in 2018, was among them. On the brink of bankruptcy in late 2019, with shares down to $1.4, Nio’s stock shot up in the second half of 2020, briefly surpassing $60 in January 2021. By that point, the company was worth more than $90 billion, making it the fourth most valuable car firm in the world after Tesla, Toyota and Volkswagen. (Nio still exists: its sales are steadily expanding and its stock is back down below $10.)

Nio’s wild stock market ride is an object lesson in the operation of speculative finance. What happened to the company in the early months of 2020, just before it became a meme stock, is an object lesson in something rather less run-of-the-mill: the Hefei Model. The city of Hefei, 250 miles west of Shanghai, is the capital of Anhui province and a prefecture-level city, an administrative rank held by around three hundred Chinese cities (more significant centres, such as Jinan or Ningbo, have vice-provincial rank). Hefei is also an economic success story: its GDP more than quadrupled between 2010 and 2022 while China’s merely doubled. This performance has been attributed to the city government’s economic strategy, which involves selectively deploying investment funds it controls to organise the growth of manufacturing supply chains in high-tech sectors. Having decided that electric vehicles should be a priority sector, the city government invested the equivalent of $1 billion in Nio in April 2020, at a time when the company was short of funding and its valuation was low. As part of the deal, Nio moved its headquarters from Shanghai to Hefei. Hefei profited handsomely from the operation, cashing out of most of its stake within a year – thanks, in part, to the lockdown meme stock traders.

The ingredients of the Hefei Model can be traced back several decades. Ever since the late Mao era, the city has benefited from the presence of one of China’s leading research institutions, the University of Science and Technology of China – which ranks among the top universities in the world in certain hard sciences and engineering sub-disciplines. Hefei’s foremost development zone – the Hefei National High-tech Industry Development Zone, to the west of the city centre – was set up in the early 1990s as part of the very first batch of national high-tech development zones in China.

Hefei isn’t a hedge fund. Its municipal bureaus and investment vehicles are concerned with jobs and industry, from securing land for manufacturing facilities to ensuring that supplier networks for major firms are, to the extent that this is possible, based in the city. This has sometimes come at a cost – at least in the short term. In the wake of the financial crisis of 2008, city officials saw an opportunity to invest in a struggling technology company called BOE. They pulled the funding for a new subway line and put it into BOE, on the condition that the company build a plant in Hefei. The relationship has been successful: the city has invested in further plants and BOE has created thousands of jobs there (it’s now the world’s leading manufacturer of TV screens). In 2020, a ‘supply chain boss system’ was introduced, allowing a high-ranking municipal official to assume responsibility over planning in each of sixteen key supply chains in the city. For instance, Hefei’s top official, party secretary Yu Aihua, has been charged with overseeing the semiconductor supply chain – a significant role given China’s rivalry with the US.

The city government uses a triumvirate of investment platforms – Hefei Jiantou, Hefei Chantou and Hefei Xingtai – to acquire minority stakes in privately owned companies. Their combined assets have already reached 780 billion yuan (more than $100 billion). Investments are often made in partnership with other actors – a provincial-level government fund, for instance, or a Chinese investment group. The city authorities don’t aim to take direct control of the firms they target for investment and the platforms impose a degree of separation between administrative bureaus and corporate decision-making. Divestment from a company is expected once the city’s objectives – defined in terms of supply chain development – are met. In March 2022, it completed its financial arsenal by launching the Hefei High-Quality Development Guidance Fund which, private equity-style, operates as a ‘fund of funds’, attracting outside capital into dozens of subordinate funds (47 had been set up as of March 2023) covering ‘seed, angel, scientific innovation and production’ investments. While Hefei’s investment funds are under the purview of the city government, they do not usually rely on money from the city budget. Being profitable across their investments is part of these funds’ mandate, and most of their profits are retained for further investment. In the event of financial vulnerability, the funds would turn first to capital markets, or banks, or other corporate entities for financial support – not to the city budget.

There is nothing exceptional in governments supporting industrial development. European states have always done so, if to a fluctuating degree. And state intervention is common in car manufacturing. Toyota was protected against foreign competition for decades until it finally broke into overseas markets in the 1960s. General Motors and Chrysler were dramatically bailed out by the USgovernment in 2008. The involvement of sub-national jurisdictions isn’t unusual either: Lower Saxony currently holds 11.8 per cent of the stock (and 20 per cent of voting rights) in Volkswagen, Europe’s largest car maker.

But the state involvement in market activity in present-day China is unparalleled in major countries. Not only is the state’s capacity to influence economic outcomes stronger than has ever been the case in the West (except for periods of war), the breadth of China’s statist panoply is remarkable: from corporate behemoths answering to Beijing to minority equity stakes in start-ups as in Hefei; from regulatory practices so fine-grained that they are closer to direction than regulation, to the sui generis role of the CCP hierarchy, which extends from party departments in government offices to party committees inside enterprises. China’s sheer size, and the revival of decentralised decision-making since the early post-Mao decades, means that a great deal of economic statecraft occurs at lower levels: provinces, cities, districts, counties, townships and so on.

Not all local authorities are as successful as Hefei. There have been cases of deteriorating competitiveness and deindustrialisation, as well as debt crises in a number of places. Corporate investment in the country is finite and local governments are vying to attract as much of it as they can. All the while, Beijing presides over the nation’s multi-scalar economy, preserving its monopoly over what is commonly referred to as ‘top-level design’. This expression, a favourite of the Xi era, affirms the supreme prerogative of China’s political centre and assigns to it an overarching ‘design’ function. Implementation happens locally, with municipal governments called on to fill out the blanks in Beijing’s blueprints.

The Hefei Model is only the most recent Chinese regional development model; earlier models include the Sunan Model in the 1980s, the Pudong Model in the 1990s and the ill-fated Chongqing Model in the 2000s – each of which had its own distinctive form of local-level statism. The Hefei Model updates statism for an age in which an overarching emphasis on technology and innovation meets the expansive logic of financialisation, which is reshaping modes of state involvement in the economy. In The New China Playbook, Keyu Jin characterises Hefei as an exemplar of the ‘mayor economy’. Jin doesn’t explain the source of the phrase, though Wang Minzheng, an official of Yunnan’s provincial government and a former mayor of the prefecture-level city of Zhaotong, wrote a well-received treatise called Mayor Economics in 2010. ‘In the mayor economy,’ Jin writes, ‘local governments have strong incentives to help promising businesses overcome barriers and to foster innovation in their locality. Adam Smith’s concept of invisible hands working behind the scenes is, in the case of China, replaced by the thousand-arm Buddha’s extended and very visible hands.’ (Her book relies heavily on allegories and similes of this sort.)

Jin argues that, in contradistinction to the West’s free market economy, China has a ‘hybrid economy’ combining the multi-scalar statism of the ‘mayor economy’ and elements of the market economy. She claims that a new political-economic model is taking shape under Xi Jinping, replacing the ‘old playbook’ that defined the post-Mao reform era up to the 2010s. In order to catch up with Western countries, Chinese leaders took ‘short cuts’, focusing on GDP growth even when it meant bending the rules, wasting resources and degrading the environment. The ‘new playbook’, by contrast, involves less cronyism (she cites Xi’s anti-corruption campaign) and better regulation. It also prioritises technological innovation and environmental sustainability, while seeking to respond to the demand of younger people for a better quality of life.

‘In China,’ Jin writes, ‘the mayor economy rivals the market economy in importance.’ But does any such rivalry exist? Political discourse tends to frame policy issues as a matter of state v. market. This can be misleading, however, because it conflates two distinct spheres of economic reality: the mechanism for allocating resources and the identity of the resources’ owners. A state-owned enterprise can respond to market signals – in fact, it usually does – and conversely a privately owned firm may choose, or be compelled, to make hires, purchases and sales via non-market channels. For instance, China’s largest car manufacturer, SAIC, a state-owned firm, competes with both private and government-controlled firms to sell its vehicles. In Western countries, it’s not unheard of for governments to impose operational decisions on private enterprises, though this power is usually employed only in times of war or other emergencies, and is made possible by legal instruments such as the US’s Defence Production Act.

Until the early 1990s, China’s planning apparatus still set prices for the products of most industrial firms. In the 1980s, market prices existed alongside government-mandated prices in a ‘dual-track pricing system’. That system disappeared around the time the Fourteenth Congress, held in 1992, declared China a ‘socialist market economy’. The allocation mechanism for goods, services, labour and capital became, by default, the market. China has unambiguously been a market economy for three decades now, and it is on this basis that Chinese enterprises operate.

Far from the mayor economy running up against the market economy, the market economy is its foundation. Statism operates via the market. When, in April 2020, the Hefei government directed an investment fund under its control to purchase a minority stake in Nio, this was carried out as a financial transaction between two corporate entities. When the timing was right, the city cashed out of some of its shareholding. The market – or rather, the financial markets – acted as a conduit for state influence over the economy.

For decades now, the CCP has focused its efforts on shaping, rather than replacing, the market economy. Western commentators often characterise this economic paradigm as a matter of ‘regime survival’: in order to escape the fate of the Eastern Bloc, China’s leaders harness strategic resources, co-opting supporters and denying access to potential opponents, while creating the economic growth necessary to mollify the broader population. But this interpretation can hardly account for what’s happening in Hefei.

Jin sidesteps the ‘regime survival’ thesis. Instead, she offers two alternative explanations. ‘In China,’ she writes, ‘an interventionist state is rooted in paternalism, a hallmark of government in China since Confucian times ... it is based on the conviction that intervention by a senior person is justified if it benefits a junior person.’ Like an authoritarian parent (the ‘Tiger Mom’ gets a mention), the Chinese Communist Party believes it should clamp down on inappropriate behaviour in economic life in the name of individual morality as well as collective stability. Confucianism aside, Jin argues that the government is well placed to correct China’s ‘weak institutions’, by which she means a less robust legal system than in Western countries and a ‘primitive financial system’ unable to match the sophistication of US capital markets. ‘A powerful state,’ she argues, ‘is especially effective in an economy’s infancy, when market institutions are still a work in progress.’ This is a line of reasoning familiar to students of orthodox institutional economics; even neoclassical doctrinaires will accept that government intervention can be called on to address market failures and ‘institutional flaws and loopholes’.

While there may be a measure of truth in this account, there is another explanation for economic statism in today’s China. It has to do with the self-propelling dynamic of capital accumulation. The most recent data from China’s National Bureau of Statistics put the number of state-controlled enterprises at 362,000 in 2022 (up from 227,000 in 2013). A recent study cited in Jin’s work, led by an economist at Tsinghua University, estimated that there are also more than a hundred thousand privately owned enterprises that have minority equity investments from the state. Only a tiny fraction of state-connected firms in China have a direct link to the central government in Beijing. The more typical arrangement involves degrees of separation at a sub-national level: a medium-sized firm based in a prefecture-level city, say, could be the subsidiary of another firm, which could in turn be partly owned by a city-controlled investment vehicle.

The directive to accumulate capital for the state is reflected in the guidelines produced by the central government’s State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) which detail how to manage state-owned corporate assets and advocate completing the transition from the old statist method of ‘managing enterprises’ to the new one of ‘managing capital’. The phrase ‘managing capital’ implies that government bureaus overseeing state-invested firms should not take direct charge of business operations. Instead, they should assume the role of an asset manager overseeing a portfolio of corporate investments and focus on expanding the value of the capital under their watch. Since its creation two decades ago, SASAC has been pushing the ‘rate of preservation and growth of state-owned capital’ as a central performance metric in the state sector. In the Chinese system, state-owned capital may be sustaining its own expansionary momentum.

Jin accepts as given a significant change in the Chinese economic system since Xi Jinping came to power in 2012. Students of Chinese economic policy have certainly witnessed their fair share of declarations about things being ‘new’ in the last twelve years. We have seen the advent of the ‘new normal’ (新常态), the ‘new era’ (新时代), the ‘new type of whole-state system for breakthroughs in core technologies’ (关键核心技术攻关的新型举国体制) and, more recently, the ‘new development pattern’ (新发展格局) in tandem with the ‘new security pattern’ (新安全格局). Taken together, these reflect a gradual reordering of priorities: from export and investment-driven growth to a slower growth rate increasingly driven by innovation and consumption. At the same time, a heightened emphasis on national security under Xi, coupled with the expanding sanctions and export controls imposed by the Trump and Biden administrations, has produced an unprecedented emphasis on technological self-reliance in critical areas such as semiconductors.

Jin’s claim that there is a ‘new playbook’ might be overstated, but it’s true enough that there is an upgraded economic strategy. At the same time, the underlying structures of the PRC economy have never felt so stable, or so consolidated, as during the last two decades. In the 1980s, Deng Xiaoping oversaw the end of collective agriculture, the emergence of small private businesses, the rapid growth of market exchange for goods and services alongside central planning and the introduction of foreign investment. In the 1990s, government-mandated prices were phased out; large-scale private companies entered the scene; the fiscal, monetary and financial systems were overhauled; and the entire public sector was dramatically restructured, with the loss of millions of jobs. The last two decades have seen nothing like the structural transformations of those years. For all the talk of ‘rebalancing’ China’s economy, relative levels of investment and consumption have remained steady since the mid-2000s. The contributions of the public and private sectors to economic activity have also been stable, if with an increased intermingling as a result of minority shareholding. Any significant breakthrough, whether planned or unforeseen, will occur in the context of an ensconced economic system.

https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v46/n05/nathan-sperber/the-mayor-economy

=========================

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FszCOibYn3U

The Economist The West Doesn’t Want You to Hear About China

For years, the West has told one simple story about China’s Belt & Road: a global debt trap. The truth is far more uncomfortable — and far more dangerous for China itself.

Based on Keyu Jin’s The New China Playbook and firsthand reporting, this episode reveals what actually happens on the ground — from Kenya to Pakistan, Sri Lanka to Greece.

In 2019, a train ride through Kenya exposed China’s biggest global gamble: $1 trillion invested. 150+ countries involved. Stunning infrastructure — and terrified recipients. This is not the Western “debt trap” narrative. This is not Chinese “win-win” propaganda. This is the story nobody wants to tell.

In this episode, you’ll uncover:

— Why Kenya’s $3.8B railway may bankrupt the country

— How Pakistan owes China $90B it cannot repay

— Why Sri Lanka leased a strategic port for 99 years

— Why Zambian workers revolted against Chinese managers

— Why Greece succeeded — and most others failed

— How China exported the “Mayor Economy” and why it backfired

From Hambantota to Gwadar, Piraeus to Collum Mine, this investigation follows a devastating pattern.

China didn’t build a debt trap for the world. China built a trap for itself.

The same system that fueled China’s rise — debt-driven growth, decentralized competition, GDP obsession — collapsed once exported to countries without China’s institutions.

The result? Over $1 trillion spent buying resentment instead of influence.

This is the story of:

David Kimani — terrified on a beautiful train

Rahim — a fisherman displaced by an empty port

Joseph — a miner asking for skills, not slogans

And China — discovering you can’t export a development model

Belt & Road isn’t over. Projects continue. Debt grows. But the bet both sides made? No one knows yet who truly lost.

Disclaimer: This video presents independent analysis and interpretation based on research and firsthand reporting. AI-generated voice used for clarity. Not endorsed by any individuals or institutions mentioned.

=====================

A charismatic 37-year-old, Burkina Faso's military ruler Capt Ibrahim Traoré has skilfully built the persona of a pan-Africanist leader determined to free his nation from what he regards as the clutches of Western imperialism and neo-colonialism.

His message has resonated across Africa and beyond, with his admirers seeing him as following in the footsteps of African heroes like Burkina Faso's very own Thomas Sankara - a Marxist revolutionary who is sometimes referred to as "Africa's Che Guevara".

"Traoré's impact is huge. I have even heard politicians and authors in countries like Kenya [in East Africa] say: 'This is it. He is the man'," Beverly Ochieng, a senior researcher at global consultancy firm Control Risks, told the BBC.

"His messages reflect the age we are living in, when many Africans are questioning the relationship with the West, and why there is still so much poverty in such a resource-rich continent," she said.

After seizing power in a coup in 2022, Traoré's regime ditched former colonial power France in favour of a strong alliance with Russia, that has included the deployment of a Russian paramilitary brigade, and adopted left-wing economic policies.

This included setting up a state-owned mining company, requiring foreign firms to give it a 15% stake in their local operations and to transfer skills to Burkinabé people.

The rule also applied to Russian miner Nordgold, which was given a licence in late April for its latest investment in Burkina Faso's gold industry.

As part of what Traoré calls a "revolution" to ensure Burkina Faso benefits from its mineral wealth, the junta is also building a gold refinery and establishing national gold reserves for the first time in the nation's history.

However, Western-owned firms appear to be facing a tough time, with Australia-headquartered Sarama Resources launching arbitration proceedings against Burkina Faso in late 2024 following the withdrawal of an exploration licence.

The junta has also nationalised two gold mines previously owned by a London-listed firm, and said last month that it planned to take control of more foreign-owned mines.

Enoch Randy Aikins, a researcher at South Africa's Institute for Security Studies, told the BBC that Traoré's radical reforms had increased his popularity in Africa.

"He is now arguably Africa's most popular, if not favourite, president," Mr Aikins said.

His popularity has been fuelled through social media, including many misleading posts intended to bolster his revolutionary image.

AI-generated videos of music stars like R Kelly, Rihanna, Justin Bieber and Beyoncé are seen immortalising him through song - though they have done nothing of the sort.

====================

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

- By Gus Leonisky at 31 Jan 2026 - 4:30pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

"benevolence"....

Wolves in sheep’s clothing: The dark side of Western benevolence

The debate over aid for Africa raises a vital concern: Is the true cost a loss of sovereignty?

BY Maxwell Boamah Amofa

Western engagement in Africa has for too long centered on humanitarian aid, portraying the continent as impoverished. However, beneath this veil of cooperation lie systemic issues that perpetuate dependency and obstruct true progress. History reminds us that ‘generosity’ often comes with hidden costs that stall the continent’s development.

A new position of the European Commission that came to the light last May is that aid to so-called poor countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Middle East should be attached to the strategic interests of the European Union.

“These [partnership] packages will reinforce the link between external action and internal priorities, such as energy security, the supply of critical raw materials,” European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and Budget Commissioner Piotr Serafin stated.

While this recalibration signals a pragmatic albeit controversial new step, history suggests that Western engagement with Africa, since its early encounters, has predominantly been entangled with material and strategic interests, including extracting raw materials and influencing socio-political structures.

The old story in new clothingAfrica has always attracted European powers due to its vast resources and youthful population, a reason for its colonial invasion and exploitation under the guise of humanitarianism, codenamed a “civilizing mission.”

The striking resemblance between the civilizing mission during the colonial period and some aid schemes in the 21st century speaks to one thing: that aid comes with a veil that must be uncovered to reveal its true cost.

The situation in the Sahel serves as a poignant example. Recently, aid was withdrawn/suspended from Burkina, Mali and Niger despite these countries grappling with armed insurgents, many of which can be traced back to NATO’s 2011 invasion of Libya. This was largely a result of their decision to channel their internal sovereign path to development.

In Niger alone, EU budgetary assistance worth 500 million euros from 2021-2024 for education, governance and sustainable development, including about 75 million euros in military support, were all suspended. While Niger benefitted from this development and humanitarian aid in previous years, the main goals of the aid included controlling the spread of global terrorism, as well as the upsurge of migrants seeking to enter Europe through Niger and to protect European mining interests.

Aid with stringsConcerning migration, following the EU-Africa Valletta summit in November 2015, the EU adopted the European Union Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF), focusing on what was considered irregular migration. Nigerien authorities were then enticed with funding from France, and pressured politically to pass a restrictive law to tackle what was considered irregular migration, despite fierce resistance from the local population.

While Nigeriens themselves are not well-known for migrating, it was targeted at migrants that travel though Niger on their way to Europe, due to its strategic location. The resistance from the people, however, was primarily due to the fact that the country’s economy heavily relies on migrants. Furthermore, the initiative did not include local actors in its adoption, while the local population experiences the brunt of its effect, including restricting the freedom of movement of Nigeriens within their country as well as within ECOWAS (the Economic Community of West African States).

The situation is worse when it comes to other social matters, such as regulating LGBT. Following the criminalization of LGBT in Uganda for instance, Norway and the Netherlands reportedly froze about $9 million in aid, with Denmark rescinding its aid to the Ugandan government, despite the country relying on it for 20% of its annual budget. Not even a healthcare loan from the World Bank was spared.

As Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of Ghana, argued,the arrival of aid brought with it conditions that restricted the political decision-making of the newly independent governments. In this way, former imperial powers continued to maintain control over the governments and budgets of their former colonies.

“Very unequal” partnershipEconomically, Europe significantly benefits from Africa’s mineral resources. Niger’s uranium exports to the EU are a key example. Niger’s uranium ore comprises around 25% of the supply used by European nuclear power plants. While most uranium produced in Niger goes to the EU, its main importer within the bloc is France, where around 70 percent of electricity is generated from nuclear power.

This reliance grew after the last 230 mines in France were closed down in the early 2000s. With this act, the unspoken calculation was evident: polluting Niger is cheaper than polluting France.

Orano, a French mining company engaged in uranium extraction in Niger, has long been accused of releasing atmospheric radon-222 gas, a substance linked to lung cancer, in its town of operation, Arlit. Findings from a study conducted in 2000 revealed that “the death rates due to respiratory infection in the [mining] town of Arlit in Niger is about 16.19%, twice that of the national average of 8.54%.”

Niger’s former energy minister, Mahaman Laouan Gaya, in 2023 described the partnership with France as “very unequal.” He stressed that in 2010, Niger exported €3.5 billion ($3.8 billion) worth of uranium to France, but Niger only received €459 million.

This came at a time when The Spectacles, a Nigeria-based media outlet, alleged that France had bought Niger’s uranium at $0.80/kg, far below the market price at the time of around $200, while Orano continued to take a disproportionate share of uranium produce in Niger.

These actions compelled the military government of Niger to nationalize one of its uranium mines. “Faced with the irresponsible, illegal, and unfair behavior by Orano, a company owned by the French state, a state openly hostile toward Niger since July 26, 2023 … the government of Niger has decided, in full sovereignty, to nationalize Somair,” the authorities stated.

Weaponized narrativesWestern NGOs and some humanitarian agencies have been the medium through which most humanitarian aid reaches the shores of Africa. It’s not uncommon that they use media featuring African children taken in unknown villages, far beyond the sprawling African cities, to back stereotypes, and depict the continent as a region dominated by corruption, conflicts, human rights violations, hunger, poverty and a lack of social amenities.

These narratives are extensively trumpeted by some of the media companies, reinforcing the perception that Africa is dependent and dysfunctional, costing the continent a staggering $4.2 billion in inflated interest payments annually. Investors and policymakers have begun to absorb these narratives; they label loans to the continent high-risk investments, and consequently charge higher interest rates than there would be if the continent was considered economically and politically stable, peaceful, credible and investor-friendly.

These portrayals can be used in perpetrating more deliberately targeted acts of sabotage. In 2024, for instance, David Hundeyin, a Nigerian investigative journalist, allegedly rejected a bribe offered by Dialogue Earth, a London-based NGO, to sabotage the Dangote oil refinery in Nigeria. The construction of the facility had been hailed as a major breakthrough for Nigeria’s oil industry; it ranks above Europe’s largest refineries in terms of production and has significantly reduced the country’s reliance on petroleum imports.

“Last week I received 800,000 Naira ($500) offer from an International NGO called Dialogue Earth (Formerly known China Dialogue Trust) to write an article essentially saying that Dangote Refinery is terrible for the environment because something something environmental concern, something something climate change, something something energy transition policy, something something COP28,” he shared on his official X page.

“Wolves in sheep’s clothing”One of the prominent players in this aid scheme was the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), an organization tasked with the obligation of disbursing capital and development assistance to so-called “developing countries” which was shut down by US President Donald Trump last year. The organization’s reasoning had been rooted in the idea of John F. Kennedy, that American security was linked to the economic progress and stability of other countries.

The agency disbursed almost $44 billion in the 2023 fiscal year alone; about $12.1 billion was allocatedto Sub-Saharan Africa.

However, despite the huge financial investment, many sub-Saharan African countries remain mired in economic struggles, some of them, such as Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger and Chad, primarily due to years of struggle against armed insurgents. Even though the United Nations has warned that “This money (funding for terrorist groups) can come from legitimate sources, for example from business profits and charitable organizations, or from illegal activities including trafficking in weapons, drugs or people, or kidnapping,” little is known about which charitable organizations fund terrorist activity in Africa, an act Scott Perry, a US congressman, believes USAID cannot be exonerated.

“Your (American tax payers’) money $697 million plus shipment of cash, funds ISIS, Al-Qaeda, Boko Haram, ISIS Khorasan, terrorist training camp. That’s what it is funding,” he stated. President Trump referred to the organization as “governed by some lunatics” while tech billionaire Elon Musk stated “it’s time for the criminal agency to die.”

Dr. Arikana Chihombori-Quao, former African Union ambassador to the US, was even more blunt, calling the agency “wolves in sheep’s clothing, which carry out nefarious activities in the African continent and destabilize governments through divide and conquer.”

Her statements emphasized the fact, that while a fraction of the funding went into delivering essential services, their acts were largely politically motivated, explaining its inability to deliver significant improvement in the living conditions of the people where it operated. The complexities surrounding the work of USAID reflect the dissatisfaction with what many consider a deviation of the organization from its enshrined purpose. It allegedly engaged in acts of deceptive benevolence, hence the need for it to be disbanded.

In a nutshell, the question of aid for Africa primarily concerns what the true cost of such aid is. African countries should re-assess and possibly disband some aid schemes. The process might be slow and painful, but as Thomas Sankara once said, “it’s either Africans take champagne for few or safe drinking water for all.”

Maxwell Boamah Amofahttps://www.rt.com/africa/631582-true-cost-of-western-aid-for-africa/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.