Search

Recent comments

- energy vs energy....

1 hour 53 min ago - killing kids....

4 hours 50 min ago - the die is cast....

6 hours 42 min ago - SICKO.....

7 hours 3 min ago - be brave, albo....

9 hours 33 min ago - epstein class....

10 hours 38 min ago - in writing....

10 hours 49 min ago - hoped....

12 hours 49 min ago - murdering kids....

13 hours 50 min ago - saving....

14 hours 18 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

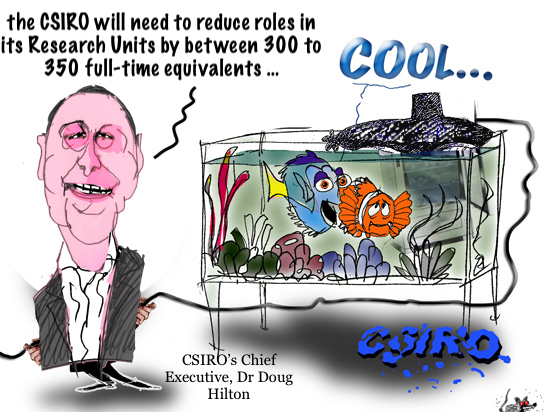

come and use our empty labs! we've sacked our scientists.....

Back in April 2024, in the context of a newly announce ‘Made in Australia’ policy, MWM wrote about our flat-lined manufacturing as a percentage of GDP (5%) and our plummeting economic complexity world ranking (105th).

The science of sacking. Be gone CSIRO scientists!

by Rex Patrick

We did not blame the Albanese Government for this … it’s taken many governments, all focussed predominantly on exporting our rocks and fossil fuels, to get this to happen. With optimism we wrote of new opportunities to fix the manufacturing percentage and the economic complexity numbers.

Our optimism was caveated on the need for strong and effective leadership. The question was, did Albanese have what it takes? “I guess we’ll see, in due course”, we proposed.

Wrong courseOn 18 November last year CSIRO’s Chief Executive, Dr Doug Hilton, issued a statement of intent for the organisation. Embedded in the announcement were the words, “the organisation will need to reduce roles in its Research Units by between 300 to 350 full-time equivalent …”

As we sit at 105th position in the world’s ranking of economic complexity, down from 62nd in 1995, and the Government’s response is to reduce the number of scientists looking to determine our future.

It’s dumb and dumber stuff; literally.

The move has, rightfully, drawn attention from the parliament, with Greens’ senators Barbara Pocock and Peter Whish-Wilson, and independent Senator David Pocock initiating a Senate inquiry into the CSIRO.

Don’t blame usResponding to a question on job cuts when announcing the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, Treasurer Jim Chalmers said the Government was not to blame, pointing the finger at CSIRO’s senior leadership.

“From the government’s point of view, we’ve been increasing their resourcing, $45 million extra last time, $233 million extra this time and that’s because we believe in the crucial role that science broadly and the CSIRO plays in the future of our economy.”

“How the CSIRO manages their budget is a matter for them and their Board, they’ve made it clear that the pressures on their budget have not come from Government cuts, on the contrary we’ve been increasing their budget,” Dr Chalmers said.

It was akin to Prime Minister Albanese suggesting that travel allowance abuse was not his responsibility, about a week before he was forced to refer the issue to the Remuneration Tribunal.

CSIRO is an organisation that contributes directly to the nation’s future, but the Government’s washing its hands of the manner in which it’s configured.

Chalmers’ statement is disingenuous.

A Freedom Of Information (FIO) request by MWM has revealed the Government has been kept fully abreast of CSIRO’s plans, including a substantive brief that goes back as far as 2024.

Scientist secrecyMWM’s FOI request was for ministerial briefs and any internal analysis on the effect of the sackings on Australia’s science capability. After initially threatening to not process the request on the grounds that it involved 2,586 pages of relevant information (which resulted in MWM narrowing the scope of the request), CSIRO has declared it has two ministerial briefs and Executive Team documents that it is not willing to share with the Australian public.

The million-dollar CSIRO top scientist doesn’t want his research peer or publicly reviewed.

The two briefs that are being withheld from the public are ministerial briefs, but that’s not stopping CSIRO from calling them cabinet documents. CSIRO acknowledged that the briefs have not been to Cabinet.

I appears CSIRO is good at science and awful at administrative law (perhaps being awful suits them). The reasoning provided in the FOI decision will fail on review.

Shrinking violetsRecognising the fragility (or perhaps, improperness) of their Cabinet exemption claim, CSIRO also asserts that disclosure of their work will take them from almost seven-digit salaried tall scientist to wilted violets unable to function.

It’s a case of “our advice is fearless, although we actually fear anyone but the minister seeing it’.

MWM will submit on appeal that this sort of advice is advice the minister should have no regard to. We will also ask under cross examination if the CEO thinks his salary allows him to do anything other than give the most candid advice.

DehumanisingAnother reason the public can’t see the documents is because doing so “could be reasonably expected to cause undue stress or other emotional or psychological harm to a large cohort of CSIRO staff (whether ultimately actually affected by the subject matter or not).”

CSIRO management thinks that announcing to their scientific team that 350 of them will lose their jobs won’t cause them undue stress or other emotional or psychological harm, but the pathway that management took to come to that decision will.

It’s nonsense on stilts.

350 scientists will go, and CSIRO’s not saying who. The best information they have is that 130-150 will go from the 715 ‘Environment’ scientist pool, 100 -110 from the 329 scientists in ‘Health and Biosecurity’ and 25-35 from the scientists 364 ‘Minerals’.

They all got to spend Christmas lunch with their families contemplating their futures, yet somehow the giving of details of the sacking science will cause greater harm to them.

Perhaps the advice-cowards in Executive team weren’t listening when Senator Pocock told Hilton at Senate Estimates of a letter he’d received from a CSIRO employee writing ‘The system is not only dehumanised; it is now dehumanising.‘

Hunger Games … but not for AUKUSSenator Whish-Wilson did have a minute at the end of the Estimates hearing to question whether ‘Hunger Games’ were now being played out inside the organisation, as reported by media.

Once can only imagine the laboratory atmosphere.

Meanwhile the Albanese ministry happily obfuscates. The Government needs to control the budget so that they can properly fund economic complexity in the AUKUS shipyards of the US (15th place for economic complexity) and UK (7th place).

Australia, in their view, don’t seem to appreciate the need for domestic manufacturing and diversity of exports. They clearly believe that our future lies in exporting fossil fuel – and are granting long term approvals accordingly.

And with 150 fewer environmental scientists around, there’ll be fewer hurdles standing in the way of their plans.

Endnote: MWM has appealed CSIRO’s FOI decision to the Information Commissioner but asked that the appeal be shifted to the Administrative Review Tribunal. The appeal will not be dealt with before the Senate Inquiry concludes, something that will suit the CSIRO and Government.

https://michaelwest.com.au/the-science-of-sacking-be-gone-csiro-scientists/

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

"WORK WITH US"

CAREERS?: BROOMSTICKS, BINS AND DUSTPAN WELCOME TO COLLECT THE DEBRIS FROM THE SACKINGS....

- By Gus Leonisky at 19 Jan 2026 - 5:55am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

swayed....

Roy Green

What does it mean to be bold on the economy?Australia’s export mix is dangerously narrow. A mission-led industrial strategy is needed to build competitive advantage and lift productivity.

When the government is under pressure, Paul Keating used to say, “you have to flick the switch to vaudeville”.

It’s a great line but hardly an option for the Albanese government in the wake of tragedies at home and abroad. That said, the pressure remains to develop a bolder change narrative for Labor’s second term, if it is to justify a third, let alone beyond.

What do we mean by bold in this context? Simply that it’s not enough to tinker at the edges of the fundamental challenges facing Australia’s economy when we need to confront them head-on, without being swayed by powerful vested interests.

We know very well what the challenges are – stalled productivity with real wage stagnation, climate change and the massive task of energy transition and growing social inequalities holding us back as a modern progressive democracy.

We also know that old orthodoxies die hard and can stand in the way of new ideas and approaches. It’s hardly a surprise that while the rest of the world moves on, the generals here are fighting the last war, which in 1980s Australia was to internationalise an over-protected and under-performing economy.

The new war is to take whatever steps are necessary to transform Australia’s narrow, outdated trade and industrial structure – currently heavily weighted towards unprocessed raw materials – with a radical, far-reaching diversification of our export mix.

But the old orthodoxies are making it difficult even to identify this as a strategic objective, as became evident in last year’s Economic Reform roundtable, an event which was supposed to be about productivity but got taken over by a deregulation agenda.

Essentially, the attachment of policymakers to a doctrine of comparative advantage has allowed the resources sector to crowd out the prospect of achieving competitive advantage in higher value, knowledge-based goods and services.

This predicament is highlighted in the Harvard Atlas of Economic Complexity, which measures the diversity and research-intensity of a country’s exports. It finds that Australia’s global ranking has fallen from around 50 in the 1990s to 105 last year out of a total of 145 countries.

Some economists don’t see this as a problem and dismiss the Harvard Atlas methodology. As one put it recently, “Some people make apples and some people make oranges, and they trade with each other. What’s not to like about that?”

But it does become a problem, even an existential threat, when apples are the main or only product a country can sell, and the crop then fails. Or when apple production runs into diminishing returns while the country with oranges pursues value-adding innovation and exports on the global technology frontier.

Australia has a “comparative advantage” in resources such as iron ore, coal and gas, but the fact that these amount to more than half its exports in value terms makes the economy dangerously vulnerable to commodity price volatility, shifting trade patterns and geopolitical uncertainty.

What happens, for example, when China sources its iron ore needs from west Africa and no one wants Australia’s coal? The resulting gap is unlikely to be made up by services exports, which comprise higher education, tourism and financial and professional services.

Nor by critical minerals unless in the medium to longer term the processing can be done onshore. Currently Australia produces 50 per cent of the world’s lithium, exports 90 per cent, mainly to China, and captures a mere 0.53 per cent of its final value.

The urgent task and opportunity is to move beyond a preoccupation with comparative advantage and, like other advanced economies, to evolve a mission-led industrial strategy. This will enable us to identify existing and potential areas of competitive advantage in the largest and fastest growing global markets and value chains.

The federal government has made an important start with its Future Made in Australia plan and associated funding mechanisms, such as the National Reconstruction Fund. But it recognises that there is much more to be done in the post-mining boom context.

It will require the application of knowledge and ingenuity to the development of sovereign manufacturing capability in areas like agrifood, defence, resources value-adding and the energy transition. These areas must then be supported by sophisticated services ecosystems, including embodied artificial intelligence.

An early finding of the government’s Strategic Examination of Research and Development (R&D) was the close correlation between the decline of manufacturing, the decline of business expenditure on R&D and the decline of productivity growth. This is the vicious cycle that must now be reversed.

However, it will not be reversed by imagining Australia as a services economy underwritten by resources exports. This recalls the 1929 Brigden report’s famous representation of the country as a “giant sheep run” which had to cross-subsidise industrial protection – an unsustainable model.

Similarly, the idea that Australia’s productivity performance will be transformed by selling each other residential housing, bitcoins and piccolo lattes in a brutally mercantilist world will consign us to the prospect of dollar depreciation and debt servicing at sky high interest rates.

The great economist J M Keynes is reputed to have said, “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?” A bold new approach?

*Emeritus Professor Roy Green AM is Special Innovation Advisor at the University of Technology Sydney.

https://johnmenadue.com/post/2026/01/what-does-it-mean-to-be-bold-on-the-economy/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.