Search

Recent comments

- druggoes...

5 hours 6 min ago - uninvited....

7 hours 55 min ago - it's only queensland....

8 hours 5 min ago - sub UK subs....

10 hours 8 min ago - kill excess....

11 hours 27 min ago - unchallenged....

11 hours 37 min ago - december 31 2024...

13 hours 18 min ago - kiwis from iran....

13 hours 35 min ago - getting dimmer....

14 hours 45 min ago - overreaction....

15 hours 25 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

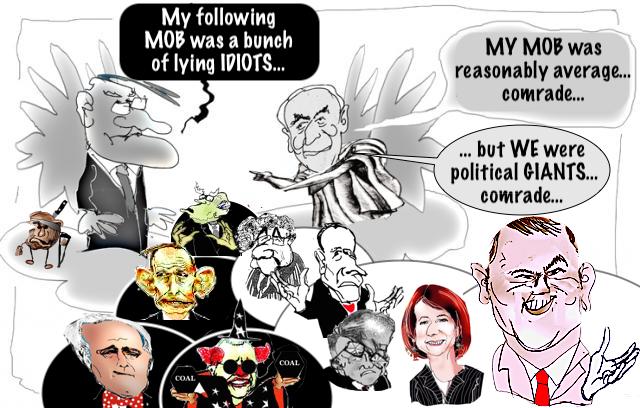

the fathers of modern politics in aussieland discuss the future....

Hunkered down in Canberra after 11 November with the ‘caretaker’ conditions imposed by the Governor-General on Malcolm Fraser, there was a sense of unreality and nagging doubt about the future. The political and social fabric of trust had been torn. Would it keep tearing?

Working with PM Fraser - the changeover - Part 1

Some of my senior Canberra colleagues, conservative and privately Liberal Party supporters, were appalled by the turn of events. I received sympathetic support from them in the difficult situation I faced which was unique because of my long association with the sacked Prime Minister. I was his personal appointment to the most senior position in the Public Service. Would I want to stay if Fraser was elected? Should I stay? Would I be asked to go? I knew the questions were being canvassed. I thought the gossip was beside the point. Not for one moment did I consider resigning.

In the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, we turned to briefings for the new Government after the election. One normally has several months to prepare. In this case we didn’t have much time. It was made more difficult because the Liberal Party had not given a great deal of thought to policy development. A Liberal Party government would be a natural return to the pre-1972 order. We hoped that Fraser’s election policy speech would give us guidance on what we should prepare for, but it was stronger on politics than policy. We had long discussions with the Public Service Board about major departmental changes that Fraser had flagged.

In the unlikely event of Whitlam being returned as Prime Minister we also prepared a briefing. We expected that Kerr would resign rather than be sacked. I also knew that Whitlam had privately speculated that he might make a symbolic point of switching the residence of the prime minister from the Lodge to Yarralumla and oblige the new governor-general to move into the Lodge. He would have enjoyed that.

I knew that we might also need to be ready for possible impeachment action against the chief justice. Mick Young privately raised it with me, although I never heard Whitlam mention impeachment. Under Section 72 of the Constitution a justice of the High Court could only be removed by the governor-general in Council ‘on an address from both Houses of the Parliament in the same session praying for such removal on the grounds of proved misbehaviour or incapacity’.

My first meeting with Fraser after his landslide victory on 13 December 1975 was in his office in Parliament House on the afternoon of Monday 15 December. It was very matter of fact; just the two of us. There was little small talk. There were awkward silences. I congratulated him on his election victory. He modestly acknowledged the success and said he appreciated my assistance in the difficult period from 11 November. He then asked me to continue as Head of the Department. That didn’t surprise me, but if he had said please go, I wouldn’t have fallen off my chair either. He said that I had behaved professionally. More importantly, although he didn’t say it, he was looking for continuity, which I supplied.

In his book, _The Unmaking of Gough_, Paul Kelly wrote: “Three days before polling day Whitlam received a phone call from John Menadue, who was now head of the Prime Minister’s Department under Malcolm Fraser. Menadue was anxious to stay on in the job if Labor was defeated but thought he should clear this with Whitlam who had originally appointed him. Whitlam told Menadue he could see no problem with this and said later he regarded it as a vindication of Menadue’s appointment in the first place.”

Much as I would have appreciated Gough Whitlam’s encouragement, such a discussion never took place. I didn’t even think of clearing it with him.

Peter Wilenski and Jim Spigelman, the other two departmental heads who had been tagged with me as being recipients of ‘jobs for the boys’, were shifted. Quickly the Fraser Government proceeded to make its own political appointments, but mostly from within the public service. The two ‘Mr Williams’ in the Treasury leaking to Fraser and Phil Lynch were never disciplined. In the early weeks of the new government, Fraser seriously considered splitting Treasury to break its monopoly over economic advice. He didn’t tell me why he didn’t act, but my view was that he had been too much the beneficiary of Treasury disloyalty to the former government, to take them on so soon.

Later Fraser commented in The Age of 6 February 1978 on how he found the Prime Minister’s Department: “The quality of the Department is noticeably good. It has been from the beginning [of my Prime Ministership]. With John Menadue I certainly had no complaints at all with the way the Department was servicing the requirements of Government.”

Under Fraser I continued to build up further the activist role of the department that I had started with Whitlam. It was necessary to be able to respond to Fraser’s wide-ranging interests and energy.

I had not known Fraser much at all before we worked together for 12 months. Our worlds did not intersect. I had met him first 20 years before, when as the new and young Member for Wannon he came to speak at Lincoln College in Adelaide. The relationship between Fraser and me worked reasonably well considering our different backgrounds but I didn’t think for a moment that it would last. On the personal side he was quite easy to work with. He was considerate to me and my family. He went out of his way to include my wife Cynthia wherever possible in dinners at Parliament House or the Lodge or travel. He was more predictable than Whitlam but didn’t generate the same level of excitement. I was kept well informed and had quick access when necessary.

Despite the bitterness of the dismissal, I found little vindictiveness in Fraser towards the public service—quite unlike the Howard Government years later. People were more likely to be judged on their ability and honesty rather than what side of the political tracks they came from. To properly inform him about the people he would be dealing with, I insisted that he be told of their party activities if it was possibly relevant. His answer, with his chin sticking out, was invariably, ‘So?’ He wasn’t interested. He won the respect of a wide range of senior officers in PM&C and I would include myself in that category.

But inevitably in a position like that I got involved in discussions on the fringe of government with Liberal Party officials and businesspeople. I increasingly felt that my home wasn’t with those people and that, inevitably, I would want to go or be asked to go. As Secretary of Cabinet, I was in regular contact with ministers. Although polite, some were suspicious of me, particularly the new-money Liberals out to prove themselves. Ministers from longer established wealthy families, particularly families on the land, like Tony Street and Doug Anthony, were more relaxed towards me. Fraser covered for me as best he could.

I was able to assess and interpret more maturely what it meant to be an outsider. As a son of the Methodist manse, I had often felt an outsider in socially conservative country towns when I’d tried to establish relationships with other boys and later girls, in school and after school. I found acceptance at school through sport. As a university scholarship holder, I also felt different. I had to study harder. At the age of 41, under Fraser, I was an outsider again. But by that time, I found I didn’t really care.

I vividly remember a lengthy discussion at the Lodge, in the early days of the new government, with Malcolm Fraser, David Kemp, Dale Budd and other members of the private office. The evening was informal and quite friendly, but I had a strong sense that I didn’t belong. But I didn’t feel perturbed as perhaps I expected. Belonging was no longer so important. It was transforming to realise that if push came to shove, I could survive as an outsider; not comfortably, but I could manage.

That realisation was assisted by Malcolm Fraser’s personal consideration for the predicament in which I was placed, amongst people most of whom bore me no ill will but whose backgrounds and attitudes were different to mine. It was a turning point for me. Until then I was much more anxious to work the system, to be an insider. From this time on it was less appealing.

This is an updated extract from Things You Learn Along the Way, 1999 - John Menadue >Tomorrow: Working with PM Fraser - The business view - Part 2

https://johnmenadue.com/post/2025/11/working-with-pm-fraser-the-changeover-part-1/

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

- By Gus Leonisky at 19 Nov 2025 - 8:11am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

PM fraser-2

John Menadue stayed on as the most senior public servant in the land, after the trauma of the Dismissal. In this 5-part series he details what life was like working with PM Fraser. Given his closeness to Whitlam, some of his conclusions are surprising.

John Menadue

Working with PM Fraser - the business view - Part 2Some of the business community, who were apoplectic about the Whitlam Government, clearly wanted me to go. A Liberal Party official in Sydney, a knight of the realm from the insurance industry, leant on Fraser to remove me.

A very senior Melbourne Liberal business leader asked me over a lunch, “Is it true that after the dismissal your department was shredding and burning files?” It was hard to accept the prejudice and ignorance of so many of those people. The same business leader later had to resign his company directorships.

Some commentators speculated that because of my Methodist origins and my ‘fierce detestation of idleness and extravagance in Government’ I was a natural ally of Fraser in cutting waste. This was partly true. The same journalist, Peter Samuel, reported five months into the new government that “Menadue remains a strong and vocal critic of the Governor-General’s action in dismissing Whitlam.” That was very true.

Early in January 1976, with senior officers in the department, I organised drinks for Mr Whitlam to wish him well. He was without bitterness, despite the injustice that had been done to him. It was important to thank and farewell him, to underline the civility and continuity of public life.

With the smell of blood in their nostrils, some ministers were determined to pursue further four of the outgoing ministers—Whitlam, Jim Cairns, Rex Connor and Lionel Murphy—involved in the attempted loan raisings.

On 21 October 1975, a few weeks before the dismissal, Bob Ellicott, the shadow attorney general, had presented a petition from Danny Sankey, a solicitor and constituent of his, to the House of Representatives stating that he wanted to prosecute the four ministers involved in the 13 December 1974 meeting of the Executive Council and asked for leave to subpoena certain loan documents. It was refused by the Whitlam Government.

On 20 November, in the middle of the election campaign, Sankey launched a private legal action against the four ministers for allegedly conspiring with each other to contravene the financial agreement which regulates loan raisings. Furthermore, he alleged that they had conspired to deceive the governor-general. When Sankey’s prosecution came on in the Queanbeyan Court in the week before the 13 December election, he asked that warrants be issued for the arrest of the four ministers.

Then in the early months of the Fraser Government there was a bolt from the blue. Billy McMahon privately approached the Secretary of the Executive Council, David Reid, who was based in the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. Reid reported to me that the former Prime Minister had approached him to provide copies of the Executive Council minutes. He refused. McMahon was quite persistent and suggested that if Reid left the documents in the letterbox at his home, he would arrange for them to be collected. After discussions with Clarrie Harders, the Secretary of the Attorney-General’s Department, we decided not to call in the police to investigate McMahon’s actions. I thought it better that the matter rest.

Ellicott was determined that the Government take over the prosecution. I advised Fraser not to because, to the best of my knowledge, there was no corruption or illegality in the attempted loan raising. The four ministers had acted legally at every step. Fraser didn’t take much persuading that that was the case. He was also persuaded that it was unwise for one government to be raking through the documents of another government and that if the matter came to court the Commonwealth Government should refuse to release them. But Ellicott was single-mindedly determined to continue. At the end of the day, Fraser said that Ellicott should not proceed. He had wrung everything he could politically out of the loan’s affair and the Executive Council meeting and to proceed further would be fruitless or even counterproductive.

As a result of Cabinet’s decision not to proceed, Ellicott later resigned as Attorney-General in September 1977. In his view, he was being blocked from what he saw as his duty as the first law officer of the Crown. Ellicott’s actions were puzzling. He was a lay preacher who had been personally welcomed to the Parliament and praised by Whitlam, although he was joining the other side. When he entered Parliament in 1974, Whitlam said that the institution of Parliament needed more men like Ellicott.

On Ellicott’s resignation, some media thought that he had resigned on the principle of not interfering with a previous government’s records. In fact, it was the opposite—he resigned because he was not allowed access.

The adversaries of 1975 were toppling one after another.

Kerr requested that I resume the regular conversations that I had had with him during the Whitlam Government. It is common practice for the Head of PM&C to have such conversations with the governor-general. I spoke to Fraser, and he agreed. As before, Kerr was eager to get a briefing on a wide range of government activities. Security, intelligence and foreign affairs were always top of the list.

At the second and all subsequent meetings, we were joined by Lady Kerr. She would stay for the full meeting, often an hour or so. She didn’t join in the conversations except for the normal courtesies. She was there to listen and support. In those discussions, Kerr conveyed very starkly his concern about his physical safety. He asked me several times to review security at Yarralumla and, to a lesser extent, at Admiralty House in Sydney. He was afraid that protesters might scale the walls and attack him. He felt very insecure. We made some checks and decided that security was adequate.

He also continually sought my view whether Labor hostility would blow over. I could not advise him what the Labor movement was likely to do but I had a pretty good idea. From Mick Young and other friends, as well as what I could read in the newspapers, I was aware of the extent of the hostility. I gave Kerr no encouragement whatsoever that the hostility was only a passing phase.

Perhaps as a thank you to Kerr, Fraser, unknown to me, wrote directly to the Queen in April 1976, proposing that the Governor-General receive the honour of Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (KCMG)— ‘Kindly call me God’. I got a rebuke from Sir Martin Charteris, the Queen’s Official Secretary, in a ‘Dear Menadue’ letter, indicating that it was unwise for the Prime Minister to be sending such a formal letter requesting a KCMG to the Queen. The letter was leaked. Charteris suggested that whilst I might think it was ‘mumbo jumbo’, it was useful to first do some preliminary informal soundings. Only in informal discussions would it be proper for the Queen to indicate whether she agreed with the proposal or not. Once it came as a formal proposal from the Australian Prime Minister, she really had no choice but to approve. Charteris said, of course, that “[the Queen] had no reluctance in approving this award.” But the message was clear. The Queen had reservations.

Increasingly Kerr became an embarrassment to Fraser, with his extravagant public lifestyle and overseas travel. He claimed he couldn’t holiday in Australia because of protests. Fraser finally cut him adrift in July 1977, glad to be rid of an embarrassment. By that time, I had gone to Japan. For a period, however, Kerr was a useful fall guy for Fraser. Kerr, rather than Fraser, was the focus of scorn and derision.

This is an updated extract from _Things You Learn Along the Way_ 1999 - John Menadue

Tomorrow: Working with PM Fraser - a country divided - Part 3

https://johnmenadue.com/post/2025/11/working-with-pm-fraser-the-business-view-part-2/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

PM fraser-3

John Menadue

Working with PM Fraser - a country divided - Part 3Malcolm Fraser never really got away from the fact that in coming to power he divided the country. That division was mirrored in his own person. In his awkwardness, he tended to push people apart.

If the Whitlam Government was over-prepared for government, the Fraser Government was under-prepared. In the three years in opposition, it did little rethink on policy. It was a matter of reclaiming its rightful position in government and performing competently.

At a discussion at the Lodge early in 1976, with his senior political colleagues and his own staff, Fraser commented that despite the brilliance and the glamour of Whitlam in 1972 against an ‘old dope like McMahon’, the Labor Party had won by only nine seats. In his view, if the Labor Party was anything like a natural party of government in Australia it would have won handsomely in those circumstances.

The lack of preparation for government and any clear direction had been highlighted in his 1975 policy speech to “give Australian industry the protection it needs,” but also claiming that a Liberal government would “make Australia competitive again.” The political rhetoric was there, but it lacked a core philosophy. Contrasting himself with the Whitlam Government, Fraser was committed above all else to managing his ministers, the public service and the economy and removing from government all waste and extravagance: “Life was not meant to be easy.”

To highlight the end of extravagance, Fraser instructed that expenditure on the reception for the new Parliament be cut. Instead of champagne we had orange juice. Fraser also tried to lower the political temperature after the frenetic days of the Whitlam Government. He told us in the department that he wanted to take politics off the front page of the newspapers.

We are all wise after the event, but the Fraser Government missed the opportunity, with a strong Prime Minister and with a record majority, to initiate reforms, particularly in industry structure. Business was protected and inward-looking. Australia had to become part of the global economy and develop its economic relations with Asia on a competitive basis. Nothing much changed, though. Hard-nosed policy development in opposition, free of the burden of government, should have better equipped the Liberals. There was no coherent framework in government.

Fraser toyed with monetarism, the Treasury fad at the time; inflation could be broken by controlling the money supply. It didn’t work. In the Fraser years, demand was not controlled through the budget and large wage increases resulted in high inflation and rising unemployment.

In fairness, however, it should be said there are convenient lapses of memory by the critics. At the time no ministers, policy advisers in the Liberal Party or business or media commentators were seriously espousing any credible alternatives. The dumping on Fraser, for failed economic policies, came well after the event.

The manner of the Fraser Government seizing power sapped its confidence and resolution from day one. I thought a nagging doubt was always there. It was tentative on tough issues. Government spending was a clear example. Ten years later, Fraser acknowledged to his biographer, Philip Ayres, that “he should have undertaken more radical surgery on the public sector in his first year.” He believed that Treasury gave him bad early advice on spending cuts. Most important of all, he was nervous about creating further social division and hardship with large expenditure cuts.

He went to great pains to try to build a consensus with the ACTU and Bob Hawke. Tony Street, the Minister for Employment and Industrial Relations, was the most reasonable person in the Cabinet and close to Fraser. They went to school together. As a result, in the early months of the Government there were compromises on Medibank, the abolition of the Prices Justification Tribunal and secret ballots in trade unions.

Fraser was interventionist across all ministerial portfolios, but Treasury resisted. It paid the price. We briefed Fraser on the regular quarterly Treasury forecasts and monthly Reserve Bank reports. He instructed Treasurer Phil Lynch that Treasury should send copies directly to him. It delayed. I wrote to Fred Wheeler confirming the Prime Minister’s requirements. Reluctantly Treasury complied but invariably the reports arrived at the last moment and too late for proper consideration. Fraser was angry with this continued defiance. The outcome was that in November, just after I had left the department, Fraser split Treasury into two: Treasury and Finance. It was for one purpose: to reduce Treasury influence. Treasury was always slow to learn that its first duty was to serve the Government.

On economic affairs Fraser was not a Thatcherite. He didn’t have any truck with ‘rational economics’ or the ‘radical right’. As a Western District grazier, he saw the world differently. People who had privilege and opportunity had responsibilities, particularly towards the underprivileged. There was a sense of noblesse oblige, and of an important role for the public sector to play.

Whitlam had mistakenly left his ministers to run their own affairs. Fraser was determined not to make the same mistake. He did it by his own strong personality and the much stronger position that Liberal leaders traditionally hold in Liberal Cabinets. He curbed ministers and restricted the number of their private staff much more than ever before. Most ministers were refused press secretaries and leakages were investigated by the Federal Police. Ministerial decisions were brought under his control. It infuriated his colleagues, but they scarcely said ‘boo’. Former ministers who now say they stood up to him must have attended different meetings to the ones I attended.

Matters came to Cabinet that really should have been left to ministers or perhaps attended to in private consultation with the Prime Minister. He was concerned about reinforcing his own authority, in a party and government that had a record majority. He was never under threat but always seemed wary.

The Whitlam Cabinet had been active and interventionist, but in this Fraser put Whitlam in the shade, as the public record shows. In the first year of the Whitlam Government, 1973, there were 1700 Cabinet submissions. In the first year of the Fraser Government there were 1900 and, at the peak in 1978, they had risen to 2700. There was an explosion in Cabinet business, whereas by all expectations the Fraser Government was going to be less interventionist and make fewer decisions. It was frenetic. Cabinet meetings were called at very short notice. Ministers did not get sufficient notice. The workload that we had in the department in that first year with Fraser was far more than anything we had known with the Whitlam Government. He would ring at any time of the night.

Years later when I spoke to Tammy Fraser about Malcolm’s plans, perhaps relaxing and spending more time at Nareen, his family property in western Victoria, she commented, “John, at Nareen he is bored shitless.” Seeing him in Cabinet and with his ministers I knew exactly what she meant. He wanted to relax but wasn’t sure how to. It was work, work, work. Outside politics he had few real interests.

At the first Cabinet I saw at first hand his great affection for black Africa. He was queried by a colleague about support which the Australian Council of Churches was providing for ‘guerrilla movements in Africa’. I was flabbergasted by Fraser’s response. He said that ‘the liberation movements in Southern Africa should be supported. Ian Smith [in Southern Rhodesia] is mad. I don’t just mean politically stupid. I mean he is clinically mad and the sooner he is got out of the way the better’. I was gasping. This was not what I had expected of a conservative Prime Minister.

A senior PM&C colleague later described to me how in a visit to South Africa in 1986 as a Co-Chairman of the Eminent Persons Group (EPG), Fraser called on Nelson Mandela in gaol. The EPG had been established by the Commonwealth Heads of Government to encourage a process of political dialogue to end apartheid in South Africa. Fraser described Mandela, to my colleague, as the most impressive man he had ever met. After 23 years in jail Nelson Mandela asked Fraser if Don Bradman was still alive. Fraser sent him a bat autographed by Bradman.

In the caretaker period after 11 November there were continuing and well-sourced reports about Indonesian troop movements which suggested a likely Indonesian attack on Dili. It came on 7 December 1975. Before the attack, however, Fraser had discussed the position in Timor and Indonesia with Tony Eggleton, who was the Federal Secretary of the Liberal Party, and me. Eggleton had been a press secretary to three Liberal Prime Ministers and the Director of Naval Public Relations. Fraser asked me to prepare a paper on the possibility of Australian military intervention in Timor against the Indonesians. He outlined two possibilities: either that Australia would intervene under a United Nations flag; or that Australia would do it unilaterally. He wanted information about the physical capabilities of the Australian defence forces to mount such a military operation against the Indonesians. Fortunately, Tony Eggleton was also opposed. He didn’t describe it as a mad hatter idea, but I think that is basically what he thought. I suggested it would be wise for Fraser to sleep on it before we did anything further. No further action was requested.

Later Fraser asked Alan Renouf, the Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs, to raise the Indonesian annexation of Timor in the United Nations. The department, however, was reluctant to intervene between Indonesia and Portugal. Renouf recruited Arthur Tange, the Secretary of Defence and former Foreign Affairs head, and respected by Fraser, to try to dissuade him. The problem was overcome by Portugal itself taking the matter to the United Nations.

In June 1976, Cynthia and I travelled with Fraser to Japan and China. At the last moment Susan Peacock, wife of the Foreign Minister, Andrew Peacock, could not make the trip and Cynthia was invited in her place. It was a great opportunity to be in Japan again and to see our oldest daughter, Susan, who was a Rotary student in Okayama in western Japan. In Tokyo, Fraser signed the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation between Australia and Japan, which Whitlam had first proposed to Japanese Prime Minister Tanaka, three years earlier. It was pleasant to see it signed after long years of bureaucratic delay on both sides. On the instructions of Fraser, I gave the Secretary of our Foreign Affairs Department a deadline for completion of negotiations.

In China, Fraser received a tumultuous welcome, very similar to the welcome Whitlam had received in 1973. In Whitlam’s case he was welcomed following the establishment of diplomatic relations. In Fraser’s case his anti-Soviet stand won him points with the Chinese.

The visit proved very eventful. By accident, the record of discussion of Fraser with Premier Hua Kuo-Feng was distributed by our Embassy to the media in error. The record highlighted Fraser’s criticism of the Soviet Union.

That was bad enough, but real turmoil was created by the leakage to the Melbourne Herald of a late-night discussion which Fraser held with his visiting party at the Guest House. The story alleged that Fraser had proposed a ‘four power pact’ comprising the United States, China, Japan and Australia, to contain the Soviet Union. On the Great Wall the next day, Peacock, the Foreign Minister and later Australian Ambassador to USA, almost out of breath waved a cable and yelled, “Prime Minister, Prime Minister, have you seen this?” It was a cable on the Melbourne Herald story. I was under suspicion. Warren Beeby in The Australian, referred to “unreconstructed Whitlamites” who were leaking to embarrass the Fraser Government. Fraser went out of his way to tell me on the Great Wall that he did not suspect me. He didn’t need to do that, but he was very aware of my difficult position, under pressure and in hostile territory.

On the return from Beijing, Fraser was irritated by the pretensions of the British in Hong Kong. Hong Kong police impounded the pistols of the Australian Federal police officers who were guarding him. In response he cancelled a visit to Governor MacLehose and rejected a cruise on his yacht around Hong Kong Harbour the next day. Steve FitzGerald, the Australian Ambassador in Beijing, and I, with our wives and staff had no problem taking over the cruise and sampling the Governor’s wines. When senior Hong Kong officials came later to Australia, Fraser had pleasure in instructing that the pistols of their police were to be impounded.

In the United States in July, I attended with Fraser his discussions with President Ford and Secretary of State Kissinger. In Kissinger’s world of Realpolitik there was no place for waverers. You were either on the United States’ side or against. He detested the non-alignment of India. He said that he always arranged his itineraries to avoid any possibility that he might have to visit India. He adapted an old schoolboy story: ‘If you meet an Indian or a death adder on the jungle path at night, which do you kill first?’ For the Secretary of State of the most powerful nation on earth that was really something.

Fraser took a lively interest in all sorts of gadgets, especially the newest cameras and the radio telephone on his VIP aircraft. At a meeting of officials and private staff in the Hotel Okura in Tokyo, he brought in an amateur listening device he had acquired and, as a joke, placed it on the table. As the meeting started, ASIO officers dashed in shouting, “There is a listening device in here emitting a signal. Stop talking. Stop.” The toy was taken out to wry amusement. The meeting resumed. He was infatuated with intelligence and security gadgets.

His interest in intelligence gathering included checking on Whitlam’s abortive $500,000 fundraising from the Ba’ath Socialist Party in Iraq at the time of the 1975 election.

The go-between for the ALP and the Iraqis to raise the money was Henry Fischer, a Sydney businessman of central-European background and with contacts in the Middle East. Fischer took the story, unsolicited, to Murdoch in London. A reliable account of what then transpired is in _Oyster_, written by Brian Toohey and William Pinwell, and published in 1989. After action by the Commonwealth Government in the Federal Court in 1988, the text of the book was vetted by and negotiated with the Department of Foreign Affairs.

Having got the Iraqi scoop from Fischer, Murdoch swung into action. According to Toohey and Pinwell, Murdoch tried to get Fischer to persuade Whitlam to go to London to pick up the money personally and be secretly photographed in the act. Whitlam didn’t oblige. When Laurie Oakes broke the Iraqi story in the Sun News-Pictorial, Murdoch was scooped. In catch-up, he dictated his story for The Australian under the byline ‘A Special Correspondent’.

After the election of the Fraser government, the London ASIO representative was tasked from Canberra to interview Fischer. The ASIO reports distributed in Canberra made it clear that their primary information source was Murdoch. Fischer couldn’t be found. Murdoch was simultaneously playing the game from both ends: the source of the London ASIO reports that Canberra was reading and writing for The Australian.

But that was only the beginning of the story. Foreign Minister Peacock and his department were instructed to open an embassy in Baghdad as a cover for the posting of an ASIS agent, with the task of investigating Whitlam and his connections in Iraq. Alan Renouf, Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs, and his Deputy, Nick Parkinson, together with Ian Kennison, Head of ASIS, were, to say the least, disturbed that this was not a legitimate intelligence-gathering exercise.

As head of Fraser’s department, I spelled out my concern to Kennison and others and told him that he should refuse to open an ASIS office. If he felt he couldn’t refuse, he should at least insist on a written direction from Peacock, his minister. The written direction was given, the Baghdad post opened, including an ASIS agent. The post was closed within 12 months.

Years later the Hawke government appointed Justice Hope to undertake a further judicial inquiry into intelligence and security matters. I briefed Hope on the extraordinary role of ASIO and ASIS in a party-political dispute over attempted fundraisings in Iraq.

Before I leave this episode, I should say that I believe Whitlam’s attempted fundraising from Iraq was out of character. Except for this one incident, I found him, almost to a fault, sceptical of people with money and mindful of the compromise that might be involved in accepting party donations from them. “Comrade, I will be beholden to no one.” Bill Hartley, his partner in the venture, a leader of the sectarian left in the ALP in Victoria, was as unlikely a collaborator as it was possible to imagine. In ‘normal times’ it would have sent all sorts of warning bells ringing and lights flashing in Whitlam’s mind. I can only conclude that after 11 November 1975, Whitlam was so distressed that his old caution and judgment on fundraising was thrown to the wind.

This is an updated extract from Things You Learn Along the Way, 1999 John Menadue

Tomorrow: Working with PM Fraser - burying White Australia - Part 4

https://johnmenadue.com/post/2025/11/working-with-pm-fraser-a-country-divided-part-3/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

independence....

Robert Barwick

Malcolm Fraser: a decent man committed to an independent AustraliaPersonal experience and recent reflections challenge the popular caricature of Malcolm Fraser, revealing a former prime minister increasingly willing to defy orthodoxy in defence of sovereignty, justice and independence.

I was moved reading John Menadue’s recent series, “ Working with PM Fraser”. It brought back memories of my brief but productive collaboration with Malcolm Fraser in his final two years.

I first met Malcolm Fraser in January 2013. I had spent part of my childhood growing up in Ararat in the electorate of Wannon, for which he was the local MP. I can remember sitting bored in our family vehicle as a six- or seven-year-old waiting for my father to finish a constituent meeting with “the prime minister” in his electorate office. I also remember, from hearing various adult conversations over the years, that he had cried when Fraser lost the 1983 election; he had said “life wasn’t meant to be easy” (my mum loved quoting that one to us kids when we whinged); and something about him losing his trousers somewhere. All of this added up, in my mind, to a caricature of the man.

By the time I met him, however, I had developed a deeper appreciation of Fraser based on his more recent activities, rather than my perception of his time in politics. My party, the Citizens Party, has always focused on issues relating to Australia’s national sovereignty, and as Research Director I had noticed Malcolm Fraser taking strong positions that we agreed with on issues such as opposing Canadian media magnate Conrad Black’s takeover of Fairfax, opposing the Iraq war, and speaking out against Australia’s appalling mistreatment of refugees. The issue that led to our meeting was his outspoken opposition to the early talk of war against China.

In 2012, the Citizens Party published an issue of our New Citizen newspaper in which we detailed the presence of US bases and facilities in Australia, and identified the political identities who were openly talking of war with China. The strongest quotes in that feature against this emerging agenda were public statements by Malcolm Fraser, so we mailed him a copy and he agreed to meet.

In our first meeting, which included Citizens Party founder Craig Isherwood, we discussed the Asia Pivot announced by Barack Obama in 2011, which was premised on a supposed China “threat”. Mr Fraser showed he had a deep understanding of the historical origins and legal issues around tensions in the South China Sea.

Unprompted, he raised Zionist leader Isi Leibler’s attacks on him for his support for Palestinians. This was common ground, as our party had also experienced being attacked by Isi Leibler. He showed he would not be intimidated, leaving no doubt in my mind as to what position he would have taken on the Gaza conflict in the last few years.

Another unexpected area of common ground was the financial system. As we were speaking about the hangover from the global financial crisis, Fraser commented, “Repealing Glass-Steagall was a mistake.” Glass-Steagall was the 1933 US law that had separated commercial banks with deposits from speculative investment banking; its repeal in 1999 had fuelled the explosion of derivatives speculation that had imploded in 2008. At that time our party was in the middle of a major campaign for a Glass-Steagall separation of Australia’s banks. Fraser became an enthusiastic recruit to that campaign, and even wrote a submission to the 2014 Financial System Inquiry calling for an Australian Glass-Steagall law. As John Menadue observed, he was no Thatcherite.

Perhaps the most dramatic episode in our collaboration was immediately following the 22 February 2014 coup in Ukraine, when US-backed protesters drove out the Yanukovych government. On 3 March he wrote a powerful op-ed in The Guardian, Ukraine: there’s no way out unless the west understands its past mistakes, which denounced the USA’s broken promise not to expand NATO eastward. We quoted him in a Citizens Party release criticising then-PM Tony Abbott’s response to the events, which prompted the Russian news agency Tass to contact me asking for an interview with Fraser. Not many people would have been prepared to speak to Russian media in those weeks, but when I passed on the request Fraser didn’t hesitate. The resulting half-hour interview on RT’s Worlds Apart was significant, in that a senior statesman of the west sheeted home blame for the conflict on US-NATO policy. (Read a transcript of the interview by P&I contributor Susan Dirgham).

In a meeting soon after that, he was excited by the impending publication of his book, Dangerous Allies, in May 2014. He was especially proud of the promotional kicker for the book: Australia needs America for security, but Australia only needs security because of America.

In my last meeting with Malcolm Fraser, he mentioned he had been in discussion with John Menadue about starting a new political party. John mentioned this discussion in his recent series but said he had declined when Fraser queried whether he would be interested in joining such a party. As I told John last week, I got the impression from my discussion with Fraser that he considered it a real possibility, so he may not have taken John’s response as the last word and intended to keep working on him.

In early 2015 I phoned Fraser and asked him to speak at an international conference the Citizens Party planned for March 2015. He agreed but cautioned that he first had to see how he recovered from an operation he was scheduled to have a few weeks before the conference. Sadly, he didn’t survive the operation. We opened that conference with a tribute to Fraser and his abiding commitment to a truly independent Australia.

From my personal experience, which I feel John Menadue’s series confirms, Malcolm Fraser was a thoroughly decent man, who in person was different to the superficial caricature of a ruthless politician that defines him to many Australians due to the tumultuous political events of the 1970s.

End note: The television coverage following Malcolm Fraser’s death included interviews in which he acknowledged being emotionally reserved. Due to his austere, reserved demeanour I could not bring myself to call him anything other than Mr Fraser, but I did get to see a crack in that demeanour. In a meeting with him one day I nearly died with embarrassment when my SMS notification went off, which was a very loud Woody Woodpecker laugh. As I fumbled to put my phone on silent, Fraser gave us a little grin and told us a story of how he had been at a family event and all his grandchildren were absorbed in their phones. He asked what they were so interested in and they said Twitter, so afterwards he signed up to Twitter himself. When he next saw his grandchildren, he asked them how many followers they had, and each answered they had a few hundred. Smiling broadly, he told us that he had boasted: “I have 30,000!”

https://johnmenadue.com/post/2025/12/455402-2/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.