Search

Recent comments

- figurehead....

1 hour 39 min ago - jewish blood....

2 hours 38 min ago - tickled royals....

2 hours 46 min ago - cow bells....

16 hours 38 min ago - exiled....

21 hours 40 min ago - whitewashing a turd....

22 hours 40 min ago - send him back....

1 day 9 min ago - the original...

1 day 1 hour ago - NZ leaks....

1 day 12 hours ago - help?....

1 day 12 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

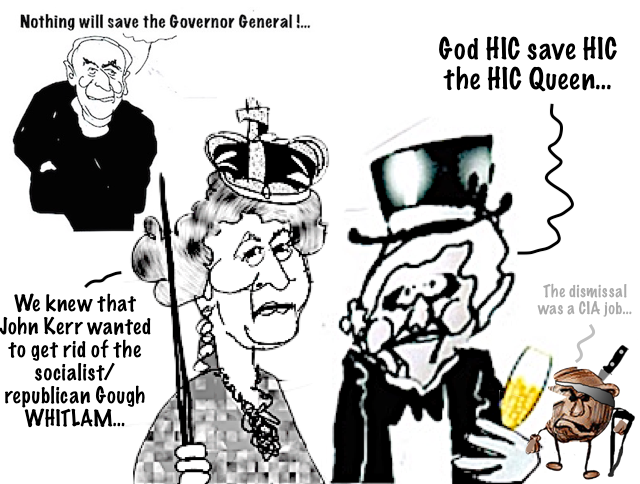

the dismissal of gough whitlam was a con job....

The first in a series of first-hand accounts of the Dismissal, from the man who was there: John Menadue.

Deceit is the one word that comes to mind when I think about the Dismissal.

Many in the Coalition, with a born-to-rule view after 23 years of conservative rule, believed that the election of the Whitlam Government in 1972 was an aberration.

More bills were defeated in the Senate in the three years of the Whitlam Government than in the previous 72 years.

Ambush and deceit

There was a dry run for a dismissal in 1974. There was much speculation then that the Coalition led by Bill Sneddon would block supply. Fortunately, governor-general Hasluck accepted Whitlam’s advice for a double dissolution and, with his help, the Senate agreed to allow supply. The Hasluck model was clear. But governor-general Sir John Kerr did not follow the Hasluck model in 1975. Instead, he sacked his prime minister.

But for a foretaste of what was to come we must go back to December 1972 when Senator Withers, the leader of the Liberals in the Senate, denied the legitimacy of the newly elected Whitlam Government. Withers threatened that, “The Senate may be called upon to protect the national interest by exercising its undoubted constitutional power.” He said that the election mandate was “dishonest”, that Whitlam’s election was a “temporary electoral insanity“ and claimed that “the government following the will of the people would be a dangerous precedent for a democratic country”.

After the Dismissal, Withers said, “for all I know my blokes might have collapsed on the 12th. I don’t know. You just hope day after day you would get through until the adjournment… There were two senators who told me they were prepared to go. I reckon we had another week. If I had got through that week, then you would look at the following week. I would have lost them sometime after 20 November onwards. I know I would have lost them in the run-up to 30 November, but it wouldn’t have been two then, it would have been ten.”

Kerr intervened prematurely in a political contest which saved Malcolm Fraser but greatly damaged Gough Whitlam.

We also now know, through Jenny Hocking’s research, that there were five Liberal Senators who had decided a week before the Dismissal that they would abstain on any future bill to defer supply. That would allow supply to pass. While searching through Senator Missen’s records, Hocking found clear evidence that five Liberal Senators were prepared to allow supply, not by supporting it, but by not voting to defer Supply. They would abstain.

“Senator Missen’s diary vindicates the view that a political solution to the crisis was at hand and that the Senate was about to ‘break’ and refutes the historical claims of both Fraser and Kerr that the Senate would never have passed supply. Missen recounts that he, together with four fellow dissident Liberal senators — Jessop, Bessell, Laucke, and Bonner — had made a pact, just days before the Dismissal. Missen writes, in his entry for the week ending 3 November 1975, that “a bleak position” for the Opposition had developed, and if ‘it was a choice between voting for or against the Budget Bills, we would all abstain and allow the Budget to pass’. The five rebels had ‘quietly reached this resolution on the Tuesday’ – that is, one week before the dismissal… This agreement would have had critical consequences for Whitlam’s decision to call the half-Senate election, had that election been granted contingent on the passage of supply.”

In addition, the late David Smith, the official secretary to the governor-general, had told us that if Whitlam had not gone to the governor-general to recommend a half-Senate election, the events of 11 November simply would not have occurred.

It was a courtesy of Whitlam to tell the governor-general in advance what he was coming to see him about. This enabled Kerr to set the trap by ensuring that he dismissed the Whitlam Government before the prime minister could recommend a half-Senate election.

The governor-general would have been duty bound to accept the advice of the prime minister for an election. But Kerr beat him to the punch by sacking him first.

Whitlam was within a whisker of victory on 11 November, but little did he know it at the time.

Even before the Dismissal and breaking of conventions developed over centuries that upper houses should not block money bills, we had a breach of the well-established convention in Australia that on retirement or death of a senator he/she would be replaced by a person from the same party. With the appointment of Senator Murphy to the High Court, the government expected that the NSW premier would support a Labor Senator to replace him. That did not occur. That breach of convention was followed later that year and with very serious consequences. Labor Senator Bert Milner from Queensland died. But Joh Bjelke-Petersen appointed a stooge, Pat Field, to replace Milner. Field was a Labor renegade who voted consistently with the Coalition when he was appointed to the Senate. But for that breach of convention, the Coalition would never have been able to defer supply. Milner’s death gave Fraser the extra vote he needed.

One other convention that we thought was critical was the separation of powers between the executive and the judiciary. There was a serious breach of this convention.

In March 1975, Kerr approached the vice-chancellor of the Australian National University with an unusual proposition: the formation of a group within the university that could, in confidence and without the knowledge of the prime minister, advise on the nature and extent of the powers of the governor-general. Included in that tutorial group was a very senior judicial figure, Sir Anthony Mason, a sitting justice of the High Court.

Kerr spoke of Mason as “fortifying me for the action I was to take" and that Mason was “a critical part in my thinking”. Mason even drafted a letter of dismissal but which Kerr did not use. Mason did not divulge any of this to his fellow High Court justices.

Mason told Kerr that he disagreed with the advice of the solicitor-general, Maurice Byers, that the reserve power had fallen into disuse.

Byers had been quite emphatic. “The reserve power can’t exist (because) you can’t have an autocratic power which is destructive of the granted authority of the people. They just can’t co-exist. Therefore, you can’t have a reserve power because you are saying ‘the governor-general can override the people’s choice’… And that is nonsense…Reserve powers are nonsense."

We also learned later that the Queen’s private secretary told Kerr that he had the power to dismiss the Whitlam Government and that it would do no harm to the Palace in doing so, but, in fact, would do the Palace some good.

Ellicott, the shadow attorney-general, produced an opinion which he widely circulated on 16 October, that the governor-general should dismiss the government. To Whitlam, Kerr described the opinion as “bullshit”. In the department, we received a colourful briefing from Whitlam on what Kerr thought of Ellicott’s opinion.

But Mason, and later chief justice Barwick, assured Kerr that the divine right of kings was still alive, and he could sack the people’s choice. They were not neutral judges of our highest court. They were partisan political operators.

Kerr “was particularly concerned that the High Court on 24 June 1975, with reasons given on 30 September 1975, had decided that, in the view of the majority (Barwick, Gibbs, Stephen and Mason), governor-general Hasluck should not have granted a double dissolution in April 1974, in respect of the Petroleum and Minerals Authority Bill". Kerr was concerned about the implications of the PMA decision in the use of the Crown discretion which would be necessary to dismiss a government.

That is why Kerr went and saw Barwick on 10 November, to make sure the latter would support his proposed action against the government. He was lobbying the High Court in advance.

As we know, Barwick, quite improperly, expressed his opinion supporting the proposed dismissal of the Whitlam Government to justices Stephen and Mason because Kerr was concerned that these two High Court justices had moved away from Barwick in two other cases, the Senate (Representation of Territories) Act and the Australian Assistance Plan Act. Barwick was confident Gibbs would support him.

Mason did, however, tell Kerr that if he was considering dismissing the prime minister, he should warn him in advance. Kerr never did that. Mason also told Kerr that, even if there was a risk that Whitlam might sack him, it was a risk he should be prepared to take.

It is interesting to speculate what the electoral outcome might have been in an election for both houses had Whitlam gone to the election with all the advantages of incumbency. Opinion polls showed there was a substantial swing to the government because of the actions of the Coalition in blocking supply.

Mason was concerned about his role. He wrote to Kerr, “I have felt some difficulty in my participation in the discussions, for it may appear to some that we are engaged in the consideration of important questions which may sooner or later come before the High Court for decision. No doubt, the questions which you have in mind are presently hypothetical. Unfortunately, the hypothetical questions of today have a distressing habit of becoming the actual questions of tomorrow. I, therefore, doubt whether it would be proper for me to become a member of the group on a continuing basis.”

In retrospect, Whitlam and many others, including me, were overconfident about securing supply.

Cabinet discussed attaching a clause to the supply bills to ensure that they came back to the House of Representatives before going to the governor-general for assent. The Cabinet was of the view, however, that this was unnecessary and could be counterproductive in antagonising the Senate.

I also suggested to Whitlam that I travel to London to brief John Bunting, our High Commissioner there, who was the secretary of Prime Minister and Cabinet before me. The visit would be to ensure that the Palace was properly briefed in case the prime minister had to act quickly for the dismissal of the governor-general. Whitlam said that would not be necessary.

We also suggested the prime minister might invite the governor-general to address the Senate or perhaps both Houses of Parliament, urging the passage of the supply bills. My note of 11 December 1975 referred to many suggestions made by the department about how advice should be given to the governor-general, including letters to him setting out the government’s position.

The advice given by Whitlam to the governor-general was oral, in the expectation that the Opposition would give way.

The prime minister did not believe it was correct to involve the governor-general in such political enterprises. In retrospect, it might have flushed out the governor-general, but Whitlam was always very conscious of the proper role of the governor-general and that he should not involve him politically.

In mid-1975, Kerr told Whitlam that he would be prepared to sign appropriation bills on the advice of his ministers even if they had not been passed by the Senate. Whitlam told Kerr that he would not be prepared to advise this course because he was sure that if the governor-general did sign such bills, a challenge in the High Court was certain, and the government would lose. This could precipitate a general election, and the government would be forced to campaign in an election on what would be widely interpreted as an illegal act. This offer was made by Kerr. It was not proposed by Whitlam. This confirmed in Whitlam’s mind more than anything else that Kerr was supportive of the government. That was also my interpretation. How naïve we were!

Kerr must have been shaken by action which Whitlam took against Queensland governor Hannah. The practice was that the senior governor held a “dormant commission” and became the administrator of the Commonwealth in the absence of the governor-general. Hannah was the senior state governor.

He had made his speech at a long lunch on 15 October which was extremely hostile to the Whitlam Government. He had caught the Bjelke-Petersen infection. Whitlam decided immediately that Hannah’s dormant commission should be withdrawn so that he could not become the administrator in the governor-general’s absence.

At Whitlam’s direction, we drafted a letter in the department to sign to go to Buckingham Palace via Kerr, terminating Hannah’s dormant commission. Kerr received the letter but decided that the letter should go direct from the prime minister to Buckingham Palace.

It was sent on 17 October and Hannah’s dormant commission was terminated on 26 October. That action clearly put Kerr on notice that a similar fate might befall him. The mechanics and time delay in Whitlam sacking Kerr in a crisis made that a most unlikely possibility. It may not have been in Whitlam’s mind, but it would certainly have preyed on Kerr’s mind.

At a dinner at Government House for the Malaysian prime minister on 16 October, Whitlam said in a joking, but not very sensitive, way that “it could be a race between me getting to the Queen to get you dismissed and you terminating my commission as prime minister". I am told that everyone laughed, but Kerr must have seen the danger.

The evidence is overwhelming that Kerr was obsessed about losing his job. As journalist Paul Kelly put it in power terms, “Kerr had decided to dismiss Whitlam before Whitlam had a chance to dismiss him. It was elemental, that primitive. But Kerr sought a loftier motive than merely saving his own job. His justification was to preserve the reputation and importance of the Crown.”

Certain of Kerr’s obsession about Whitlam dismissing him, Fraser piled on the pressure even more. According to Kelly, on 6 November in what Fraser described as his “most important meeting with the governor-general", Fraser said: “I now told the governor-general that if Australia did not get an election, the Opposition would have no choice but to be highly critical of him. We would have to say he’d failed his duty to the nation."

Fraser knew Kerr’s weakness better than the prime minister. He was threatening the governor-general.

The 11 November was a day I will never forget. I was working for Whitlam in the morning and Fraser in the afternoon.

I attended an early meeting in the prime minister’s office with Whitlam, Fred Daly, Frank Crean, Malcolm Fraser, Phil Lynch and Doug Anthony. It was designed to see if some resolution of the impasse over supply was possible. It became clear that a solution was not at hand.

But before the meeting, and not known to the prime minister or me, I learned that Fraser had earlier been in touch with Frank Ley, the Chief Electoral Commissioner. Ley was concerned and asked me to inform the prime minister. I made a note: “The advice given to Fraser, which he conveyed to me, was that any decision on a pre-Christmas election had to be made quickly, perhaps that day or early next week at the latest. This was obviously very valuable advice for Fraser. I passed this information from Ley to the prime minister.”

After that meeting, I contacted Kerr’s office to make an appointment for the prime minister to see the governor-general concerning the half-Senate election. The time proposed was not convenient for Kerr. Clearly, the timing of the coup was underway, but little did I expect it.

There was a lot of to-ing and fro-ing on the timing until the prime minister rang Kerr directly and made an appointment.

Meetings at Government House that day were carefully arranged with Fraser hiding in one of the backrooms while waiting for the nod that Whitlam had been sacked and he would be asked to form a government

I continued in the department, helping prepare papers for the half-Senate election which would involve the states issuing writs. I gave the papers to the prime minister and awaited his return from Government House to put in process arrangements for the election.

Then the bombshell dropped

David Smith, the official secretary at Government House, rang and told me that the Whitlam Government had been dismissed. I must have gone onto autopilot for a while. There were things that had to be done.

I informed Geoff Yeend, my deputy, Alan Cooley, the head of the Public Service Board, and Fred Wheeler, the secretary of Treasury.

Whitlam’s driver then rang me and told me that “the boss” wanted to see me urgently. I drove immediately to the Lodge. Gough was at the table eating a steak. He said, “Comrade, the bastard Kerr has done a Game on me.” In the 1930s, governor Game had dismissed the NSW Lang Labor Government. Gough asked me to call the secretary of the Attorney-General’s Department. I was overcoming my shock; I told Gough that it would not be appropriate to call public servants but that he should call Kep Enderby, who was the previous attorney-general. Several other ex-ministers came and there was discussion on what Whitlam and the Labor caucus should do.

I received a telephone call from my personal secretary Elaine Miller that Fraser wanted to see me. I told her to tell Fraser that she couldn’t find me. She rang about 10 minutes later and said, “the prime minister, Malcolm Fraser, wants to see you urgently”. I decided that I should leave the meeting with Whitlam and go to Parliament House to meet Fraser in his office. I often wondered afterwards whether I should have explained better to Whitlam my departure from the Lodge.

Not surprisingly, there was a lot of noise and activity in Fraser’s office when I got there. I agreed to continue as secretary of Prime Minister and Cabinet, at least in the caretaker period.,

We set in motion the necessary election arrangements, preparations for the swearing in of new ministers the next day and the first Fraser Government Cabinet meeting. And a lot more I can’t recall!

At the end of the day, Fraser, my new boss, asked me to join him for drinks at the Commonwealth Club of which I was not a member by choice. I had a glass of red wine but declined an invitation for dinner.

I limped home for consolation with my family.

After the dismissal of the government, Kerr was concerned that the speaker of the House of Representatives was at his gate at Yarralumla, seeking to see him to convey a message that the House of Representatives had passed a motion calling for the dismissal of the new Fraser Government and that the governor-general should reinstall the Whitlam Government. With supply passed and with the speaker at his gate, Kerr was disturbed. He spoke to Mason again for advice. Mason told Kerr that he need not see the speaker. That was extraordinary.

This was the second dismissal of the day.

It was OK for Kerr to deceive his prime minister but it was not OK to deceive the leader of the Opposition who had just lost a vote of confidence in the House of Representatives.

The next day, when I was at Government House for the swearing-in of the new Fraser ministry, Kerr told the new ministers that he had considered whether he should see the speaker the day before but “having committed myself to a certain course of action I could not go back”. That was extraordinary, refusing to see the speaker.

King Charles I had been executed for defying the speaker and the House of Commons.

https://johnmenadue.com/post/2025/11/ambush-and-deceit/

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

SEE ALSO:

https://yourdemocracy.net/drupal/node/46141

https://yourdemocracy.net/drupal/node/42653

The Governor-General should be put in his proper place — as a ceremonial figure on leave from The merry Widow...

Bill Hayden (1981)

SEE ALSO:

lest we forget .....

- By Gus Leonisky at 4 Nov 2025 - 3:33am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

dismissal #2....

The second part in a series of first-hand accounts of the Dismissal, from the man who was there: John Menadue.

John Menadue

The second Dismissal – the loans affair and meetings with KerrJustice Anthony Mason advised Sir John Kerr by phone not to see the speaker on the afternoon of Gough Whitlam’s dismissal. It was the second dismissal of the day.

The office of speaker was central in the centuries-long struggle between Parliament and the Monarchy in the UK. The history of the speakership shows several speakers dying violent deaths, while others were imprisoned, impeached or expelled from office. In our House of Representatives, there is still a pantomime when a new speaker is elected. He/she is dragged unwillingly to the chair because historically being speaker could be dangerous – for defying the monarch.

In the UK in the early 1640s, there was a major dispute between Parliament and King Charles. It led to a civil war and the execution of a king. In that dispute speaker Lenthall of the House of Commons addressed King Charles.

“May it please your majesty. I have neither eyes to see nor tongue to speak but as the House is pleased to direct me, whose servant I am. I humbly beg your Majesty’s pardon that I cannot now give any other answer then this to what your Majesty is pleased to demand of me. I am the servant of the House, not the King”

I’m sure that in the UK, the Queen would not have refused to see the speaker in similar circumstances.

Fortunately, Kerr wasn’t executed, but he was driven from office.

The proposed fundraising by Rex Connor had thrown the government off course. The loan raising was unsuccessful and there was no illegality. However, it contributed to the public view that the government was unstable.

The government was not performing well. There were a lot of prima donnas in the Cabinet and Whitlam was not good at managing them. Unfortunately, in 1974 the world was in economic turmoil following the doubling of oil prices. Unemployment in the US rose by 7% and inflation by 11%. In Australia, we were not immune to this.

Further governance, as we found in the department, was made extremely difficult with government survival threatened, with the prospect of refusal of supply a daily problem. And the Murdoch media was determined to cripple the government. Good policy and performance were made very difficult.

It is also important to note that when Malcolm Fraser sought to justify his action on refusing supply, he said it was not due to the loans affair but was because of the sacking of Bill Robertson, the head of ASIS. I will turn to that later and explain the role that Robertson, together with the CIA and MI6, played in the Dismissal

One reason why the loans affair became such a political issue was that senior officers in Treasury leaked continually to the Opposition and the media about the loan raising. Treasury had chummy relations with companies like Morgan Stanley and didn’t want to upset such relationships. They also believed, genuinely, that the loan raising was bad policy. They were right on that, but by then Whitlam had stopped listening to them.

Whitlam often said that Treasury “took their bat home “when the government rejected their advice. He had lost confidence in Treasury and Treasury reciprocated his hostility by leaking continually against the government to shadow treasurer Phil Lynch.

Kerr was not present at the critical Executive Council meeting on the $4 billion loan raising. That was not unusual. He signed the minute the next day. He never objected to the loan raising that Connor was seeking to develop Australia’s mineral resources and to avoid them falling into foreign hands.

There was a further possible fundraising of $2 billion and Kerr was present at the Executive Council meeting and was quite enthusiastic about it.

Kerr was worried about how his role was being portrayed, particularly in the Murdoch media. He complained to Whitlam about it. He insisted that if Fraser was to form a government, there was to be no Royal Commission into the loans affair and his role. Fraser agreed.

Whitlam decided reluctantly that Connor should resign. He asked me to secure Connors’ resignation! I thought it unusual that a public servant should ask a Cabinet minister to resign. But, with Clarrie Harders, secretary of the Attorney-General’s Department, we went down to Connor’s office. I conveyed Whitlam’s request for his resignation. He told me to “piss off” although Paul Keating has a more colourful account: that I was told to “bugger off.” In any event, I didn’t get the resignation. Whitlam had to attend to it himself.

Meetings with Kerr

In my regular meetings with Kerr before the Dismissal, he inquired many times about how the prime minister was faring. I took this to mean — and I’m sure what Kerr intended — that he was very supportive of the prime minister and concerned about his personal welfare. Kerr approvingly told me that he had heard comments that former prime minister Menzies had said that Fraser was “wet behind the ears” to try on refusal of supply.

Kerr spoke to me about his plans for an expanded role for himself. He was an able, articulate man, still quite young and did not see himself as a person retiring to Yarralumla. He was seeking to make and find a role for himself. He asked me on many occasions what his role should be in speaking engagements and the extent to which he should discuss public issues in a way which, whilst not causing embarrassment to the government, demonstrated that he had a view of his own. He asked my advice on whether he should hold press conferences and how he should respond to press queries. He was also most anxious to travel and to project the role of the governor-general abroad. I said to him that this did raise problems as he was the Queen’s representative in Australia, but it might be difficult in some countries to explain, particularly in countries which did not have a British background, what a Queen’s representative in Australia was when he was travelling overseas. We discussed these issues at considerable length. I said that he should be careful.

In later trips to Asia, he had meetings with prime ministers and heads of state. He believed that he could play a useful role.

Subsequently, when I was ambassador in Japan, Sir Zelman Cowen was governor-general elect. He was visiting Japan and was keen to meet the Japanese emperor. I discussed with the Gaimusho, the Japanese Ministry of Foreign affairs, about the possibility of a call on the emperor. I was told that as governor-general elect it would be possible for the emperor to see Cowen. However, the Gaimusho made it clear that if Cowen was the governor-general, he would not be able to see the emperor. This was because the governor-general represented the Queen in Australia, but did not represent anyone when he was overseas.

The prime minister was very cautious about an expanded role for the governor-general. The previous governor-general, Hasluck, was “commander-in-chief, in and over the Commonwealth of Australia”. Whitlam insisted that Kerr’s role and aspirations be more limited. From the beginning of his term, on 11 July 1974, he was “commander-in-chief of the Defence Force of Australia”.

As the political crises deepened, I decided not to continue my meetings with Kerr. The prime minister was the government adviser, and I was anxious to ensure that Kerr did not receive any mixed message from me.

After the Dismissal, I had several meetings with Kerr. He was clearly very concerned about the demonstrations across the country. He sought some reassurances from me as he thought I might have contact with people in the Labor Party. I told him that Mick Young, a close friend of mine, was certain that the demonstrations would continue and increase. Kerr asked me several times about his personal safety.

Perhaps demonstrators might jump over the fence at Yarralumla!

At all these meetings, Lady Kerr was present. That was most unusual. I was surprised but it reflected how uncertain and worried Kerr was.

Some have suggested that it was a mistake by Whitlam that, after the Dismissal, he should have focused on blocking supply in the Senate to ensure that the new Fraser Government would not obtain money! There is a touch of wisdom after the event to argue this. Whitlam later told me that at least two Liberal Senators would not refuse supply to the new Fraser Government. Perhaps Whitlam focused too much on securing support in the House of Representatives rather than the Senate. In part, I think that was due to confusion at the time but also to Whitlam’s strong belief that the House of Representatives was the chamber where governments were made and unmade and not the Senate.

The ALP had also contributed to the political confusion with its view about an expanded role for the Senate. Senator Murphy promoted an increasingly activist Senate, particularly its committees. In Opposition, led by Murphy, the ALP had attempted to block supply on several occasions. It would come to rue this, even though it didn’t happen and couldn’t happen because of the numbers in the Senate. We will be reminded of this on the 50th anniversary.

I was not on the steps of Parliament House when Whitlam delivered his memorable speech about “Kerr’s cur, and nothing will save the governor-general”.

I was back in the department in West Block preparing papers for the swearing in of the new government the next day.

Subsequently, I recall a discussion with Paul Keating that he was on the steps at Parliament House providing Whitlam with a megaphone. Keating told me that he had said to Gough, “I’m from the NSW right and we would call out the troops”. Whitlam was never of that mind.

It was surprising that Bob Hawke did not at least call a one-day national strike. But Hawke was seldom helpful to the Whitlam Government.

The Dismissal pushed me more to the left politically. I had been too trusting of the powerful and wealthy. I saw at first hand that a governor-general, justices of the High Court and subsequently the Queen and her advisers were untrustworthy. They were deceitful. And the abuse of power by the Murdoch group continues.

I learned later when I was a member of the Council of the Order of Australia that Sir Harry Gibbs, the chief justice at the time, lied to me about the appointment of Lionel Murphy to the Order of Australia.

In their twilight years, Whitlam and Fraser came to respect each other. Whitlam often said to me, “unlike Kerr, Malcolm never deceived me”. He was out in the open.

I was present when Fraser presented a book to Whitlam he had just written. He inscribed it…”Dear Gough, in affection and great respect, Malcolm”. My eyes misted over.

Kerr’s cur and Whitlam had found much more in common than in their earlier years. Fraser had changed more than Whitlam.

Later, I worked in immigration with Fraser and Ian Macphee. It was the most meaningful and enjoyable time in my public life. Together, I believe we put an end to the White Australia policy. Fraser was better on that than Whitlam.

The last contact I had with Fraser was when he asked me if I was interested in joining a new party he was contemplating. I declined.

Tomorrow: the role of the Palace

https://johnmenadue.com/post/2025/11/the-second-dismissal-the-loans-affair-and-meetings-with-kerr/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

the queen....

John Menadue

The Queen’s implausible denialIt beggars belief that the Queen did not know that John Kerr was planning to sack Gough Whitlam. She may not have known the detail of the coup in progress, but she knew the substance. But like Lord Nelson she pretended she did not see anything. Nonsense.

There are many reasons to reject the Queen’s cover-up and the cover-up done on her behalf. Importantly, the Queen is formally responsible for what her staff do in her name. Martin Charteris was her alter ego. We also know that the Queen was extraordinarily close to Charteris.

For his service and loyalty to the Queen, he became Sir Martin Charteris and later Lord Charteris of Amisfield. That was, in turn, topped when he became Baron Charteris of Amisfield. There is nothing here to suggest anything but a very close relationship between the Queen and Charteris. He was rewarded every step of the way for his loyal service.

Charteris wrote to Speaker Scholes after the Dismissal that “The Queen had no part in the decisions which the Governor- General must take in accordance with he Constitution”. The Queen’s Deputy Private Secretary,Sir William Heseltine added ‘The Palace was in a state of total ignorance". The same gentleman later recalled that the Queen would have adopted a “policy of political delay “if Whitlam attempted to sack Kerr. How is all that for upper class deception?

A gaggle of royals were all involved, the Queen, Prince Phillip, Prince Charles and Lord Mountbatten, the most foolish of all of them. All were aided and abetted by Charteris.

Not only did the Palace hide the truth. So also did The National Archives of Australia. The NAA doggedly refused to co-operate in the release of the Palace Letters to Hocking and the Australian community. We had a right to know. It sought to hide the role of the Palace in the sacking .Hocking and supporters had to go as far as the High Court to force the NAA’s hand. Even on the day of the release of the Palace Letters, the NAA continued to obstruct and mislead. It tried to spin the contents of the letters to the Murdoch Media. As The Monthly put it, “The NAA put its own interpretation on the documents to selected journalists before Hocking was able to see even one of them. As a result, the first headlines obediently relayed the message; the Queen ‘had no role’ in sacking Whitlam, and ‘was not told in advance’.”

We know that is nonsense. Elaborate constructions of plausible denial will just not wash. The Palace went to extraordinary lengths to whitewash the role of the Queen and the gaggle of royals around her including Charles.

Tomorrow: The Prince and the Dismissal

See also:

JENNY HOCKING. “ A Royal Green Light”: The Palace, the Governor-General and the Dismissal of the Whitlam Government

https://johnmenadue.com/post/2025/11/the-queens-implausible-denial/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

the prince....

John Menadue

The Prince and the DismissalAnthony Albanese recently told us with bated breath from Balmoral Castle that Charles “is someone who is very interested in Australia”. “Interested “would be an understatement.

Charles was a very active participant in the dismissal of Gough Whitlam 50 years ago. Don’t make any mistake about that. Charles was up to his royal ears in it. He was not politically neutral. He sided with privilege and aristocracy.

And I am also certain that our prime minister never raised the dismissal with Charles. That would have been poor form!

Not surprisingly, I am also certain that our media did not question either our prime minister or the British King about the latter’s active role in the dismissal. The National Press Club would not have been interested either.

Prince Charles has form in intervening in Australian public affairs. And then governor-general Sir John Kerr facilitated it.

In the Dismissal Dossier 2017 edition, Professor Jenny Hocking recalls the grovelling relationship that Kerr developed with Charles. “In later private letters to Prince Charles and with the most differential and subordinate genuflection ‘I have the honour to remain, Sir, your most loyal and obedient servant’ Kerr would refer to these conversations as lasting moments of treasured privilege. ‘I have the very great privilege of remembering a number of conversations which you have been kind enough to have with me in past years’.”

Hocking reveals some disturbing features in this relationship during Charles’ visit to Australia in 1974. Both Kerr and Charles were obviously worried about their job prospects. Kerr had been blessed with a startlingly frank discussion about the prince’s endless wait to ascend to the throne. Kerr discussed with Charles the suggestion that he might one day come to Australia as governor-general.

Tina Brown, in her book _The Diana Chronicles,_ says Charles “really wanted the job (as governor-general) because he saw it as a way to get the hell out of the grip of Prince Phillip and the Queen”. Who could blame him?

Kerr was sticking his nose into an area of responsibility that belonged to the prime minister and no one else. But it gives a glimpse of Kerr’s pretensions. Whitlam knew nothing about this secret discussion.

As a consolation prize for Charles, Kerr suggested to Whitlam that it would be a good idea if the Commonwealth Government purchased a large rural holding with appropriate homestead, servants, upkeep and furnishings, to encourage the Prince of Wales to make more regular and longer trips to Australia. The poor fellow did not have enough to do to keep himself occupied. Whitlam rejected the suggestion.

What a meddler!

Hocking writes that, “In the heat of early spring 1975, in New Guinea, the governor-general, Sir John Kerr, sidled up to Prince Charles and suggested a quiet chat. Their topic? The possible dismissal of the prime minister whose guest they were at the Papua New Guinea Independence Day celebrations. Kerr’s prime concern in confiding this exceptional matter of state to the Prince was, as ever, his own job security.

“Charles seemed only too pleased to let Kerr ingratiate himself. The reason was clear: Kerr was looking for friendship and support wherever he could. Charles allowed himself to be drawn into the collaboration to bring down an Australian Government.”

(In his own papers) Kerr recounts Charles’ solicitous response to the governor-general’s concern for his own possible recall by Whitlam, should Whitlam hear that Kerr was even contemplating dismissal: “but surely Sir John, the Queen should not have to accept advice that you should be recalled at the very time should this happen when you were considering having to dismiss the government”.

After the dismissal, Charles told Kerr: “What you did last year was right and the courageous thing to do.”

Mountbatten’s biographer declared that Mountbatten, Charles favourite uncle,” much admired Kerr’s courageous and constitutionally correct action" in dismissing Whitlam.

A gaggle of royals all collaborated with Kerr in the dismissal of the Whitlam Government – the Queen, Prince Philip, who called Whitlam “a socialist arsehole”, Prince Charles and Lord Mountbatten.

The serious plotting began after Prince Charles and Kerr spoke in New Guinea in September 1975.

Tomorrow: Murdoch, the Dismissal and my job in Japan

https://johnmenadue.com/post/2025/11/king-prince-charles-and-the-dismissal/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

rupert's role....

John Menadue

Murdoch, the Dismissal and my job in JapanRupert Murdoch played a critical role in the Dismissal. He knew how to bring pressure on Kerr and provided strong support for Malcolm Fraser.

Murdoch was always very interested in politics. He discussed it with me many times when I worked for him including his interest in securing endorsement as a political candidate, presumably for the National Country Party. He was quite close personally to Jack McEwen, the leader of the NCP

I was also aware of Murdoch’s interest in Kerr. After a lunch with Kerr at News Corp long before the Dismissal, Rupert was impressed by Kerr who was then a Judge of the Commonwealth Industrial Court. Rupert commented, perhaps half in jest, that Kerr would be a good editor of The Australian.

Murdoch often held soirees at Cavan with editors and managers at his rural retreat outside Canberra. On one of those soirees, 12 months before the dismissal, he invited Kerr. It was late in the afternoon and Kerr, as was his custom, had had a few drinks by the time he got to Cavan.

Ian Fitchett, the doyen of the press gallery and the chief correspondent of the Sydney Morning Herald, was present at that Cavan meeting in late 1974. Fitchett told me that Murdoch had asked Kerr to speculate on the possibilities if the Opposition refused Supply. This was then a topical issue as the Coalition had contemplated refusing supply in late 1974. But it backed off.

According to Fitchett, Kerr outlined a range of options that he might consider. This was very improper of Kerr. Murdoch tucked this away for later consideration and action as his newspapers conducted a campaign that the governor-general must act in the lead-up to the Dismissal.

Just as importantly, Murdoch was a good judge of people’s strengths and weaknesses. He knew how and when to apply pressure to Kerr.

The Murdoch papers played a major role in the events leading to the Dismissal. His papers focused very clearly and directly on Kerr’s vulnerability as Murdoch knew them so well after that detailed briefing Kerr gave him 12 months before at Cavan. The headline of 20 October 1975 in The Australian was “Fraser says Kerr must sack Whitlam”. Then there was a three-part editorial series entitled “Stalemate and Sir John” focusing on Kerr and how he should act. The last in the series was headed ‘The decision rests with Kerr”. Murdoch was putting all the heat that he possibly could on Kerr. Feature writers of The Australian referred to Kerr as the “The man in the middle”.

Kerr objected to Whitlam about the vituperative and the high-pressure way that Murdoch was mounting pressure on him. How ironic that Kerr was looking for help from Whitlam only days before he dismissed him.

Following that meeting with Kerr at Cavan in late 1974, Murdoch had a meeting with the American ambassador, Marshall Green. At that meeting, Murdoch outlined to Green the likelihood that the Whitlam Government would be dismissed in future. That information was sent by cable to the US State Department and was disclosed subsequently in WikiLeaks by Julian Assange. It did not come to attention until much later because search engines did not access the story as Murdoch was spelt with a K rather than an H.

I had lunch on 7 November 1975 at what is now The Pantry at Manuka with Rupert Murdoch and Ken Cowley. Ken ran Rupert’s Australian operations. I had a few words to say about the coverage of The Australian and the News Group in the Supply crisis. They were stoppages by journalists at News Limited for the partisan way in which Murdoch was using his papers. I told him I had cancelled my subscription to The Australian. That didn’t put him off his lunch.

In my record of 11 December 1975 about that lunch with Murdoch five weeks earlier I wrote, “Rupert Murdoch told many of his friends that Mr Fraser had informed him that the Governor-General had given him (Fraser) an assurance that if he hung on long enough there would be a general election before Christmas. He told me at that lunch… that he was quite certain that there would be an election before Christmas and an election specifically for the House of Representatives". I suggested him to him that a half Senate election was the only possibility. He rejected this view and said that he believed there would certainly be a House of Representatives election before Christmas and that he would be staying in Australia until this occurred. He was very confident of the outcome of any election and even mentioned to me the position to which I might be appointed in the event of a likely Liberal victory, Ambassador to Japan.

At that time, Rupert and I were quite close personally. He even cooked my breakfast and drove me to church when I stayed with him and Anna in the Cotswolds. Murdoch was showing concern, just before the Dismissal, for my future. I had no need to worry as Fraser had agreed with him that I would be appointed ambassador to Japan. That happened 12 months later. Rupert would not have known that, except directly from Fraser.

Murdoch denies my account of our lunch. I stand by it. He was intimately involved with Fraser in the Dismissal. And my Tokyo appointment.

He also denied that after the 1972 election he asked me to put to Whitlam that he be appointed Australian high commissioner to the UK. Whitlam refused.

I stand by that story also.

Tomorrow: What role did the CIA play?

https://johnmenadue.com/post/2025/11/murdochs-role-in-the-dismissal-and-my-job-in-japan/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

CIA in oz.....

John Menadue

The Dismissal, the role of the CIA, MI6 and Austral AmericansI was familiar with many of the events leading to the Dismissal on 11 November 1975. That knowledge was greatly increased by Professor Jenny Hocking with her long and successful campaign to have the Palace letters released.

Then, in Pearls and Irritations in May this year, articles by Jon Stanford, particularly on the role of the CIA and MI6, were very helpful. And Brian Toohey added to our knowledge in shining a light in the dark world of spies. I am indebted to them all.

The revelation that came latest to me was the role of the CIA and MI6.

I was conscious of governor-general Sir John Kerr’s great interest in security matters. That was clear in the many meetings I had with him. But I discounted direct CIA/MI6 involvement.

I have changed my mind on that as more information has become available and security reports declassified. The CIA was involved, not by supporting a military coup as in Iran or Chile, but by backing a constitutional coup by Kerr in co-operation with the Palace and MI6.

I knew the CIA was in the background. I am now confident that it was very much in the foreground together with MI6.

At the time of the Cold War and its aftermath, both major parties had differing views about security/intelligence services.

During the Cold War, the Liberal Party was supportive of the political role of the US and allied intelligence/security services. The misuse of these services for political ends was revealed to me not long after the 1975 election when Malcolm Fraser instructed foreign minister Andrew Peacock to open an embassy in Baghdad so ASIS could operate under cover to investigate Gough Whitlam’s abortive attempt before the 1975 election to raise campaign funds in Iraq.

On the other political side, the ALP had been a long-term critic of ASIO, ASIS and the CIA for their partisan political behaviour. Menzies’ politicisation of the Petrov Royal Commission rankled. Although not specific about Pine Gap, Whitlam mentioned to me many times that foreign bases were unacceptable in any country unless in an emergency or under strict United Nations mandate. I also knew of Whitlam’s reservations about ASIS. As deputy leader of the Parliamentary Labor Party, he learned about ASIS not through any Australian briefing, but from the Malaysian prime minister when he visited Malaysia in 1963.That was a real shock. I was present.

In the Cold War, the US/CIA had attempted to overthrow 72 foreign governments who refused to do what they were told. Venezuela may be the next.

Both president Nixon and Kissinger, and later president Ford, had concerns about Whitlam. His comments in December 1972 about the US bombing of Hanoi and Haiphong upset them greatly, leading to their conclusion that “Australia should be regarded as a North Vietnamese collaborator”. Australia was number 2 on Nixon’s shit list, headed only by Sweden.

At the briefing before he was appointed ambassador to Australia, Nixon told Marshall Green, “Marshall I can’t stand that c**t”. Nixon contended that Whitlam was a peacenik and was setting Australia on a very dangerous course.

The Americans were also worried about Dr Jim Cairns. To assist the selective media pressure being applied to the Whitlam Government, Cairn’s ASIO dossier was leaked to The Bulletin in 1974. That confirmed in many minds that ASIO’s loyalty was not to the Australian Government.

The key US concern was Pine Gap which, in company with its sister station in the UK, could intercept almost all the world’s electronic communications. After the 1972 election, the secretary of Defence, Sir Arthur Tange, briefed Whitlam about Pine Gap and told him that the base was operated by the Pentagon in association with our Defence Department in monitoring compliance with strategic arms limitation agreements. Sir Arthur did not tell his Prime Minister that, in fact, Pine Gap was run by the CIA. On one occasion, Tange told the US ambassador that Whitlam had not followed the brief he had provided to him on Pine Gap. Full marks for disloyalty on that. Heads of departments have been sacked for far less improper behaviour.

In Parliament, in April 1974, just before the May election, Whitlam announced that “there should not be foreign military bases, stations, installations in Australia. We will honour agreements covering existing stations. We do not favour extensions or prolongation of any of those existing ones”. The lease on Pine Gap was due to expire in December 1975. The US was appalled by that.

Pine Gap was the beginning of a string of US bases around Australia, over which Australia has little or no control. Use of our real estate is of more value to the US than AUKUS submarines. Pine Gap has supported Israeli precision bombings and assassinations of Palestinians in Gaza.

The announcement in April 1974 by Whitlam did not surprise me as some loss of judgment. It was not an off the cuff comment. It was consistent with what Whitlam often told me about foreign bases in Australia. But Whitlam never specifically mentioned Pine Gap to me. However, he did focus on Pine Gap when he discovered that the CIA operated the base.

Before Nixon was forced out in August 1974, he commissioned National Security Study Memorandum 204. It was not declassified until 2014.

As set out by James Curran in his book _Unholy Fury_: Whitlam and Nixon at War, published in 2015, US defence secretary James Schlesinger a former CIA head, in Option 1 in the National Security Study Memorandum 204 took the “hardest line” on Whitlam, Curran said. Option 1 recommended that the White House,

“begin immediately to attenuate certain ties in the US-Australia relationship on the assumption that this will induce the Whitlam Government to reverse those major elements of its foreign policy which are inimical to US interests”. Option 1 continued that if this was unsuccessful (the US) “could undermine (the Labor Government) with the Australian people, setting the stage for opposition victory”.

That could hardly be more specific. The former head of the CIA and then defence secretary was proposing “setting the stage for Opposition victory”.

Option 1 was ultimately rejected. Curran says the White House then decided to persevere with the Labor Government, to “test and clarify Whitlam’s intentions over the remainder of 1974” and make “selective use of pressure on Whitlam, if necessary”.

Toohey, in advice from a former station CIA chief in Canberra, wrote, “the pressure suddenly increased, with a new CIA station chief Milton Wonus in charge in the latter half of 1975, as well as being head of Pine Gap. He had never held a job in the covert action side of the CIA before he had been assigned the task of bringing Whitlam down”.

On 16 October 1975, Sir Michael Palliser, permanent secretary of the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office, arrived in Australia to meet the governor-general. He also saw the NSW governor Sir Rodan Cutler As Hocking relates from a study of FCO records, by October 1975, [the FCO] was actively considering possible intervention in Australian politics. The very limited nature of this visit to Australia was revealed in the fact that Sir Michael did not see either the foreign minister Don Willesee, the secretary of Foreign Affairs Alan Renouf or the secretary of PM&C – me!

What an unusual visit! A meeting with Kerr, Cutler and no one else. It seems unlikely that Sir Michael was acting on behalf of MI6, although it operated within the Foreign Office portfolio. It is more likely that he was acting to safeguard the interests of the Queen with plausible deniability.

After the May 1974 election, Justice Hope was commissioned by the Whitlam Government to lead a review of intelligence services. As part of that review Whitlam signalled to Justice Hope that he wanted the Australian intelligence agencies to distance themselves from the CIA and MI6.

Whitlam did not know that Hope was improperly passing this information on to the Five Eyes.

Hope and Robertson, the head of ASIS and Oldfield of MI6 became pivotal players in undermining the Whitlam Government. Jon Stanford describes ASIS as a branch office of MI6, sharing office accommodation and training facilities around the world.

Both ASIS and MI6 were, and are, dependent on the CIA for about 95% of their source material. So, there is no surprise that advice to our ministers is mainly recycled material from the CIA. Imperialism takes many forms!

When Hope was later conducting an inquiry into our intelligence services for the Fraser Government, he interviewed me. I outlined the ASIS/Iraqi political collaboration. In anger, Hope told me that he did not want to hear about it. I was then secretary of Trade. Hope had a love affair with ASIS.

Having been introduced by ASIS head Bill Robertson, Oldfield, chief of MI6, had developed a close working relationship with Hope. This contact with MI6 would be useful for the CIA because it needed to be careful in acting against a Commonwealth country that was a member of the Five Eyes. MI6 guidance would be helpful.

Significantly, Oldfield had previously worked in military intelligence with Martin Charteris, the Queen’s principal private secretary, who was a critical player in advising the Queen and Kerr on the Dismissal. MI6 regularly briefed the Palace on sensitive matters.

When on 21 October 1975, Whitlam dismissed Bill Robertson, the head of ASIS, over alleged activities in East Timor, he also threatened to abolish ASIS. Whitlam was very angry with Robertson. This would have been seen by Oldfield and Hope as an attack on the Five Eyes.

Whitlam advised Fraser of Robertson’s dismissal. When Fraser was later justifying his unprecedented actions in deferring supply, the main circumstance he cited was not the Loans Affair, but the dismissal of Robertson.

Robertson’s sacking also concerned the governor-general, who requested advice from the solicitor-general before he would sign the notice of dismissal. Robertson had regularly briefed Kerr on intelligence issues.

The security services in both the US and the UK were getting primed for action and to apply pressure on Kerr.

Whitlam’s speech at Port Augusta on 2 November 1975 brought out all the spooky spiders from under the rocks.

As Hocking, in Gough Whitlam, _His Time_ Vol 2, p 293, put it:

“… Whitlam accused the CIA of channelling funds into domestic Australian political matters specifically funding the National Country Party.”

He knew of two instances, he said, where the CIA had provided money for domestic political influence. Most recently the leader of the NCP, Doug Anthony, had received money — Whitlam claimed — from a CIA operative who rented Anthony’s house. While Whitlam did not name the CIA employee, Anthony soon did so. In a personal statement to Parliament, Anthony acknowledged his friendship with the former CIA operative, Richard Stallings, that he had rented his house to him and that their two families had taken holidays together, but denied any knowledge of Stallings working for the CIA.

In Washington, the US secretary of state Henry Kissinger fired off a furious telegram to the ambassador in Canberra: “Such a charge against the NCP leader Anthony could have damaging fallout on other aspects of US-Australia relations.”

Stallings, who had helped establish and was the first head of the American base at Pine Gap, had indeed worked for the CIA, but his name had not been included on the official department of foreign affairs list of declared CIA officials provided to Whitlam at his request.

“…Furious that the department had placed him in the position of potentially misleading Parliament, … he would continue to restate the allegation until the correct response was given …

“As Whitlam repeated his claims, Anthony challenged him to prove that Starlings was a former CIA operative. Whitlam prepared to do just that using the information previously provided to him by the Department of Defence … Despite the most concerted efforts of [Sir Arthur] Tange to convince both Anthony and Whitlam that they must withdraw on the grounds of national security, neither would yield.

“Tange could see no way of preventing what seemed certain to unfold over the next few days …the prime minister would answer the leader of the National Party’s question, confirming that the former head of Pine Gap had worked for the CIA and, by implication, revealing Pine Gap to be a CIA operation. The flinty Tange was horrified. This is the greatest breach of security ever, he told John Menadue. “The country will be cut adrift.”

Following Kissinger’s fury about Whitlam, which he expressed to his US ambassador, Ted Shackley, chief of the CIA East Asia Division, who had been deeply involved with Kissinger in the overthrow of the Allende Government in Chile, sent a demarche to ASIO on 8 November. He had Kissinger’s permission, he told Toohey. It said the US could not see how the issues raised by Whitlam could do other than blow the lid off installations in Australia and unless the problems could be resolved, the Americans could not see how its mutually beneficial relationships could continue.

The demarche from Shackley was sent via intermediaries to Kerr. I never saw it. I was excluded. I was not one of the Austral American club, even though I was head of the Prime Minister’s Department.

Tange received it and interpreted it as an ultimatum with the alliance at risk.

He instructed John Farrands to deliver the message to Kerr immediately, three days before the Dismissal. Farrands was Defence’s chief scientist and the Australian official most associated with, and knowledgeable about, Pine Gap. He advised Toohey of the meeting, but told Toohey that he would deny it.

The pressures were building on both the domestic and foreign fronts to sack the Whitlam Government. Kerr was ready to strike. With CIA and MI6 encouragement, he pushed Whitlam over the cliff.

Interestingly Government House guestbooks for the period went missing.

Whitlam’s ASIO file, as well as mine, have also been “culled”.

I have found intelligence agencies are prone to believe that they are better informed and more patriotic, even than prime ministers. These agencies handle a lot of material, but in my experience have poor judgment.

There is little effective oversight and accountability. There is a Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security, but members are invariably seduced by “secret” and recycled CIA material. They join the insiders club that they should be supervising. It is known as regulatory capture.

I have been grievously deceived by these agencies on several occasions.

In the House of Representatives in 1977, Gough Whitlam said,

“There is profoundly increasing evidence that foreign espionage and intelligence activities are being practised in Australia on a wide scale… I believe the evidence is so grave and so alarming in its implications that it demands the fullest explanation. The deception over the CIA and the activities of foreign installations on our soil… are an onslaught on Australia’s sovereignty.”

In July 1977, Warren Christopher, deputy secretary of state under the new Democrat president, Jimmy Carter, flew into Sydney exclusively for a brief meeting at the airport with the leader of the Opposition, Gough Whitlam. As Whitlam records in his memoirs, Christopher told me that President Carter had instructed him to say that:

“The Democratic Party and the ALP were fraternal parties. He respected deeply the democratic rights of the allies of the United States. The US administration would never again interfere in the domestic political processes of Australia. He would work with whatever government the people of Australia elected.”

Could anything be clearer than that?

On becoming prime minister, one of the first things Fraser did was to renew the Pine Gap lease.

https://johnmenadue.com/post/2025/11/the-dismissal-the-role-of-cia-mi6-and-austral-americans/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

SEE ALSO:

https://yourdemocracy.net/drupal/node/46141

https://yourdemocracy.net/drupal/node/42653