Search

Recent comments

- naked.....

9 hours 10 min ago - darkness....

9 hours 33 min ago - 2019 clean up before the storm....

14 hours 53 min ago - to death....

15 hours 32 min ago - noise....

15 hours 39 min ago - loser....

18 hours 19 min ago - relatively....

18 hours 41 min ago - eternally....

18 hours 46 min ago - success....

1 day 5 hours ago - seriously....

1 day 7 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

as trump goes delinquent, it's time to revisit the two geniuses.....

There are texts that were written a long time ago and suddenly become topical again. One of them is the closing speech in Charlie Chaplin’s film “The Great Dictator” :

“I’m sorry, but I don’t want to be an emperor. That’s not my business. I don’t want to rule or conquer anyone. I should like to help everyone – if possible – Jew, Gentile – black man – white. We all want to help one another. Human beings are like that.”

Charlie Chaplin’s appeal for democracy, peace and humanity

by Eliane Perret and Renate Dünki

This is how his famous speech begins. It points to what should be written in everyone’s heart as the basis for peaceful, equal coexistence on our planet. Only then can we carry out our tasks with a feeling of solidarity with our fellow human beings.

Of urgent topicality

And who does not know Charlie Chaplin, the great actor, best known for his silent films? For a long time, his entertaining films were an indispensable part of children’s parties and end-of-school celebrations. And many children enjoyed trying to imitate his unmistakable walk with enthusiasm and tenacity.

He later became known for films in which he addressed serious topics: “The Kid”, “Modern Times” and, of course, “The Great Dictator”. It was 1940, in the middle of the Second World War, when this film appeared on movie screens. Anyone today re-reading the final speech from this film will recognise its urgent topicality and perhaps wonder what prompted Charlie Chaplin to make it. In his autobiography, he himself gives interested readers an insight into his eventful life, which is characterised by many unexpected events and at the same time also reflects global political developments.1

‘A cloud of sadness’

Charlie Chaplin’s life began in London, where he was born on 16 April 1889. It was significant for the rest of his life that both his mother and father were well-known singers and actors who had made a name for themselves in the popular theatres of the time. His mother gave him a unburdened introduction to life in the early years of his life. However, this came to an abrupt end when she lost her voice with the slightest cold and could then no longer perform.

Just one year after Charlie was born, his mother separated from his father because he drank too much. This was the beginning of a very poor life affected by great poverty for the small family – Charlie, his mother and his older brother Sydney (although the two children also tried to contribute to the family’s livelihood by working at various jobs). In the end, their mother broke down under the demands of her barely manageable everyday life, and, with interruptions, she lived in psychiatric clinics for many years. Their father soon died as a result of his alcoholism.

A “cloud of sadness” hovered over their childhood, as Chaplin vividly phrased it. However, his mother remained important to him throughout his life. On her deathbed, he remembered her loving support with gratitude: “Even in death her expression looked troubled, as though anticipating further woes to come. How strange that her life should end here, in the environs of Hollywood, with all its absurd values – seven thousand miles from Lambeth, the soil of her heart-break. Then a flood of memories surged in upon me of her life-long struggle, her suffering, her courage and her tragic, wasted life … and I wept.”

Inner resistance – a driving force in life

There was little room for school education; Chaplin only later acquired a comprehensive education. He left school at the age of 12 because he got his first chance to take part in a stage show and eventually perform as a vaudeville comedian. This initially allowed him to contribute to the family’s livelihood, and when his brother and he were completely on their own, it became part of their way of coping with life. This led him to tour the United States at the age of twenty, where he quickly became very well known. In 1912, at the age of twenty-three, he was offered a film contract in the USA.

To this day, he is known for his unmistakable appearance – as a tramp, as he calls it, an appearance that he acquired on the spur of the moment and kept for the rest of his life: “I had no idea what make-up to put on. (…) However, on the way to the wardrobe I thought I would dress in baggy pants, big shoes, a cane and a derby hat. I wanted everything a contradiction.” (p. 145)

Over the following years, he unexpectedly made a great fortune as an actor in the emerging silent films and later as a director, composer and producer, soon accompanied and supported by his brother Sydney. It may seem surprising how Charlie Chaplin, a child from a precarious background, was able to follow such a path.2

He was less fortunate in love than in his professional career. It was only in his fourth marriage, to the much younger actress Oona O’Neill in 1943, that he finally found the long-term happiness he had longed for. Eight of Charlie Chaplin’s eleven children came from this marriage.

In a straitjacket of obedience

Born in 1889, the young Chaplin experienced the time before the First World War in the USA. The political upheavals of the time find little space in his biography. Like many others, he initially felt little of the burdens of war in his everyday life. “There were no shortages, nothing was rationed. Garden fêtes and parties for the Red Cross were organised and were an excuse for social gatherings” (p. 215), he writes. By now he enjoyed great popularity among the population. It is therefore not surprising that, when the USA had entered the war in 1917, the US government propaganda department approached him as well as two of his acquaintances and persuaded them to launch a campaign for a third war bond. He went along with this and helped spread the propaganda slogans. Naive? Careless? Who can judge him? Chaplin writes in his life story: “The highlight of our tour was an event on Wall Street in New York in front of the Treasury […] New York was depressing; the ogre of militarism was everywhere. There was no escape from it. America was cast into a matrix of obedience and every thought was secondary to the religion of war. The false buoyancy of military bands along the gloomy canon of Madison Avenue was also depressing as I heard them from the twelfth-storey window of my hotel, crawling along on their way to the Battery to embark overseas.” (p. 216f.) And at the end of the war: “Nevertheless, the Allies had won – whatever that meant. But they were not sure that they had won the peace. One thing was sure, the civilization as we had known it would never be the same – that era had gone.” (p. 224)

War was in the air again

In the years following the First World War, Chaplin produced feature-length films in which he himself appeared as an actor. For example, “The Kid”, a film in which his life story unmistakably came into play, and “Modern Times”, which dealt with the inhumane assembly line system in factories, became well-known. 1940 then saw the premiere of “The Great Dictator”, Chaplin’s first sound film, a satirical parody against fascism, but also against militarism and the American state power associated with it. A new war for the USA was brewing, and Chaplin wrote: “War was in the air again. The Nazis were on the march. How soon we forgot the First World War and its torturous four years of dying. How soon we forgot the appalling human debris: the basket cases – the armless, the legless, the sightless, the jawless, the twisted spastic cripples. Those that were not killed or wounded did not escape, for many were left with deformed minds.” (p. 386)

When in 1937, the emigrated Hungarian director Alexander Korda gave him the idea of making a film about mistaken identity because Hitler had the same small moustache as Chaplin’s “Tramp”, he did not think much of it at first. But then the idea flourished. He wanted to combine comedy and pantomime in a Hitler film. In his life story, he later reflected: “Had I known of the actual horrors of the German concentration camps, I could not have made "The Great Dictator"; I could not have made fun of the homicidal insanity of the Nazis.” (p. 387f.)

A heartfelt appeal

It took Chaplin two years to write the screenplay. When the film was half finished, he was warned that it would hardly ever be shown in England and that in the USA, the censorship of the Production Code Administration (PCA), which was founded in 1934 and to which all new films had to be submitted, would prevent it from being shown. So at first there was no getting past the American censorship authority, but then Chaplin was suddenly urged to complete his film.

Would this still have been possible at the end of 1940? When the USA entered the Second World War – shortly after the premiere of Chaplin’s film (in October 1940) – all studios had the task of supporting the US war effort. With the founding of the United States Office of War Information OWI in June 1942, the PCA was placed under the authority of the new agency. The OWI now issued the necessary licenses, without which no film could be made.

The movie became famous in particular because of its final speech. This begins with the above-mentioned, surprising words spoken by the supposed dictator Hynkel: “I’m sorry, but I don’t want to be an emperor.” But this is only surprising if you do not know that it is not delivered by the mistakenly captured Hynkel, but by his counterpart, a hairdresser from a Jewish ghetto – an appeal to the world to stand up for democracy, peace and humanity, which pulled at people’s heartstrings.

In the sights of surveillance

But even after this, Chaplin remained in the sights of American surveillance, especially also those of FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover, who was one of his fierce opponents. In particular, Chaplin was accused of making public speeches in support of Stalin’s and Roosevelt’s wish that the USA should support the Soviet Union in its fight against the Nazis through a second front. In one of his speeches, in response to his critics, he stated: “I am not a Communist, I am a human being, and I think I now the reactions of human beings. The Communists are no different from anyone else; whether they lose an arm or a leg, they suffer as all of us do, and die as all of us die. And the Communist mother is the same as any other mother. When she receives the tragic news that her sons will not return, she weeps as other mothers weep. I don’t have to be a Communist to know that, I have only to be a human being to know that.” (p. 403)

In 1947, however, he repeatedly had to answer questions before the House Un-American Activities Committee because, like many others, he was suspected of being a Marxist and a Communist because of his critical statements on American politics.

Un-American activities?

On 17 September 1952, Chaplin and his family left the United States by ship for a visit to England. Despite having lived in the USA for more than twenty years, he had always remained a British citizen. Now he wanted to attend the world premiere of his film “Limelight” and to finally show his family the country of his childhood. On the ship, he received the news that his re-entry permit to the USA, which had already been issued, was revoked. It was the Mc Carthy era, and the FBI and J.E. Hoover suspected him of “un-American activities”. The paragraph used when there was a suspicion of “morals, health or derangement, or advocacy of communism or association with communists or pro-communist organisations” was elastic enough to capture any American citizen who held an unpalatable opinion. Chaplin’s name was also, as it later turned out, on a list of names of journalists, writers and artists suspected of pro-Communist tendencies. In the period that followed, Chaplin experienced an exhausting campaign against his person. “Now I felt I was caught up in a political avalanche.” (p. 411)

This campaign was directed against the screening of his new films and kept him busy with far-fetched court cases.

Dulled by greed for profit, by the striving for power and for monopolies

He could no longer return to the USA without having to endure the most unpleasant questioning. Being an American citizen, his wife Oona was allowed to return to her home country in order to save at least the most important documents and the contents of her safe. They decided to travel to Switzerland, a neutral country at the time, and Charlie Chaplin spent the rest of his life there with his family. In 1952, he bought a property for his large family in Corsier-sur-Vevey, high above Lake Geneva. Today it has been converted into a museum, where Chaplin’s work is documented in a varied and fascinating way.

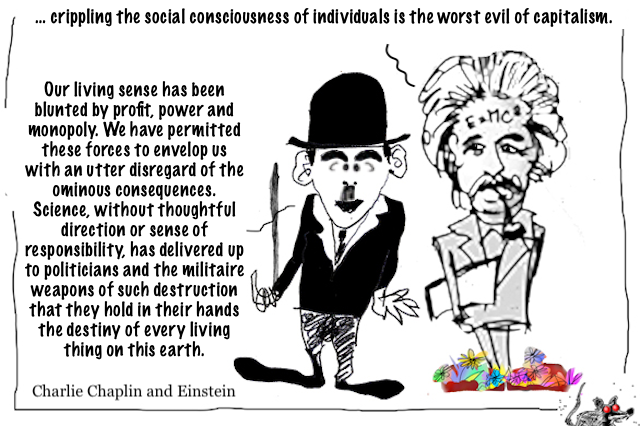

He repeatedly reflected on the world situation – as a now convinced opponent of war – in a way that is particularly thought-provoking today, when he writes: “Our living sense has been blunted by profit, power and monopoly. We have permitted these forces to envelop us with an utter disregard of the ominous consequences. Science, without thoughtful direction or sense of responsibility, has delivered up to politicians and the militaire weapons of such destruction that they hold in their hands the destiny of every living thing on this earth.” (p. 460)

Remaining a fellow human being

Despite all the fame and fortune that Charlie Chaplin was able to acquire in the course of his life, he never forgot where he came from and remained shy and reserved, as he described himself. He remained a fellow human being, as Roger Ferdinand, the president of the Societé des Auteurs et Compositeurs Dramatiquein France, noted when Chaplin was made an honorary member: “You are faithful to the memories of your childhood. You have forgotten nothing of its sadness, its bereavements; you have wanted to spare others the harm you suffered, or at least you have wanted to give everybody reason for hope.” (p. 462)

Charlie Chaplin died after a fulfilled life on Christmas Day 1977. •

------------------------

Why Socialism?

by Albert Einstein

Is it advisable for one who is not an expert on economic and social issues to express views on the subject of socialism? I believe for a number of reasons that it is.

Let us first consider the question from the point of view of scientific knowledge. It might appear that there are no essential methodological differences between astronomy and economics: scientists in both fields attempt to discover laws of general acceptability for a circumscribed group of phenomena in order to make the interconnection of these phenomena as clearly understandable as possible. But in reality such methodological differences do exist. The discovery of general laws in the field of economics is made difficult by the circumstance that observed economic phenomena are often affected by many factors which are very hard to evaluate separately. In addition, the experience which has accumulated since the beginning of the so-called civilized period of human history has—as is well known—been largely influenced and limited by causes which are by no means exclusively economic in nature. For example, most of the major states of history owed their existence to conquest. The conquering peoples established themselves, legally and economically, as the privileged class of the conquered country. They seized for themselves a monopoly of the land ownership and appointed a priesthood from among their own ranks. The priests, in control of education, made the class division of society into a permanent institution and created a system of values by which the people were thenceforth, to a large extent unconsciously, guided in their social behavior.

But historic tradition is, so to speak, of yesterday; nowhere have we really overcome what Thorstein Veblen called “the predatory phase” of human development. The observable economic facts belong to that phase and even such laws as we can derive from them are not applicable to other phases. Since the real purpose of socialism is precisely to overcome and advance beyond the predatory phase of human development, economic science in its present state can throw little light on the socialist society of the future.

Second, socialism is directed towards a social-ethical end. Science, however, cannot create ends and, even less, instill them in human beings; science, at most, can supply the means by which to attain certain ends. But the ends themselves are conceived by personalities with lofty ethical ideals and—if these ends are not stillborn, but vital and vigorous—are adopted and carried forward by those many human beings who, half unconsciously, determine the slow evolution of society.

For these reasons, we should be on our guard not to overestimate science and scientific methods when it is a question of human problems; and we should not assume that experts are the only ones who have a right to express themselves on questions affecting the organization of society.

Innumerable voices have been asserting for some time now that human society is passing through a crisis, that its stability has been gravely shattered. It is characteristic of such a situation that individuals feel indifferent or even hostile toward the group, small or large, to which they belong. In order to illustrate my meaning, let me record here a personal experience. I recently discussed with an intelligent and well-disposed man the threat of another war, which in my opinion would seriously endanger the existence of mankind, and I remarked that only a supra-national organization would offer protection from that danger. Thereupon my visitor, very calmly and coolly, said to me: “Why are you so deeply opposed to the disappearance of the human race?”

I am sure that as little as a century ago no one would have so lightly made a statement of this kind. It is the statement of a man who has striven in vain to attain an equilibrium within himself and has more or less lost hope of succeeding. It is the expression of a painful solitude and isolation from which so many people are suffering in these days. What is the cause? Is there a way out?

It is easy to raise such questions, but difficult to answer them with any degree of assurance. I must try, however, as best I can, although I am very conscious of the fact that our feelings and strivings are often contradictory and obscure and that they cannot be expressed in easy and simple formulas.

Man is, at one and the same time, a solitary being and a social being. As a solitary being, he attempts to protect his own existence and that of those who are closest to him, to satisfy his personal desires, and to develop his innate abilities. As a social being, he seeks to gain the recognition and affection of his fellow human beings, to share in their pleasures, to comfort them in their sorrows, and to improve their conditions of life. Only the existence of these varied, frequently conflicting, strivings accounts for the special character of a man, and their specific combination determines the extent to which an individual can achieve an inner equilibrium and can contribute to the well-being of society. It is quite possible that the relative strength of these two drives is, in the main, fixed by inheritance. But the personality that finally emerges is largely formed by the environment in which a man happens to find himself during his development, by the structure of the society in which he grows up, by the tradition of that society, and by its appraisal of particular types of behavior. The abstract concept “society” means to the individual human being the sum total of his direct and indirect relations to his contemporaries and to all the people of earlier generations. The individual is able to think, feel, strive, and work by himself; but he depends so much upon society—in his physical, intellectual, and emotional existence—that it is impossible to think of him, or to understand him, outside the framework of society. It is “society” which provides man with food, clothing, a home, the tools of work, language, the forms of thought, and most of the content of thought; his life is made possible through the labor and the accomplishments of the many millions past and present who are all hidden behind the small word “society.”

It is evident, therefore, that the dependence of the individual upon society is a fact of nature which cannot be abolished—just as in the case of ants and bees. However, while the whole life process of ants and bees is fixed down to the smallest detail by rigid, hereditary instincts, the social pattern and interrelationships of human beings are very variable and susceptible to change. Memory, the capacity to make new combinations, the gift of oral communication have made possible developments among human being which are not dictated by biological necessities. Such developments manifest themselves in traditions, institutions, and organizations; in literature; in scientific and engineering accomplishments; in works of art. This explains how it happens that, in a certain sense, man can influence his life through his own conduct, and that in this process conscious thinking and wanting can play a part.

Man acquires at birth, through heredity, a biological constitution which we must consider fixed and unalterable, including the natural urges which are characteristic of the human species. In addition, during his lifetime, he acquires a cultural constitution which he adopts from society through communication and through many other types of influences. It is this cultural constitution which, with the passage of time, is subject to change and which determines to a very large extent the relationship between the individual and society. Modern anthropology has taught us, through comparative investigation of so-called primitive cultures, that the social behavior of human beings may differ greatly, depending upon prevailing cultural patterns and the types of organization which predominate in society. It is on this that those who are striving to improve the lot of man may ground their hopes: human beings are not condemned, because of their biological constitution, to annihilate each other or to be at the mercy of a cruel, self-inflicted fate.

If we ask ourselves how the structure of society and the cultural attitude of man should be changed in order to make human life as satisfying as possible, we should constantly be conscious of the fact that there are certain conditions which we are unable to modify. As mentioned before, the biological nature of man is, for all practical purposes, not subject to change. Furthermore, technological and demographic developments of the last few centuries have created conditions which are here to stay. In relatively densely settled populations with the goods which are indispensable to their continued existence, an extreme division of labor and a highly-centralized productive apparatus are absolutely necessary. The time—which, looking back, seems so idyllic—is gone forever when individuals or relatively small groups could be completely self-sufficient. It is only a slight exaggeration to say that mankind constitutes even now a planetary community of production and consumption.

I have now reached the point where I may indicate briefly what to me constitutes the essence of the crisis of our time. It concerns the relationship of the individual to society. The individual has become more conscious than ever of his dependence upon society. But he does not experience this dependence as a positive asset, as an organic tie, as a protective force, but rather as a threat to his natural rights, or even to his economic existence. Moreover, his position in society is such that the egotistical drives of his make-up are constantly being accentuated, while his social drives, which are by nature weaker, progressively deteriorate. All human beings, whatever their position in society, are suffering from this process of deterioration. Unknowingly prisoners of their own egotism, they feel insecure, lonely, and deprived of the naive, simple, and unsophisticated enjoyment of life. Man can find meaning in life, short and perilous as it is, only through devoting himself to society.

The economic anarchy of capitalist society as it exists today is, in my opinion, the real source of the evil. We see before us a huge community of producers the members of which are unceasingly striving to deprive each other of the fruits of their collective labor—not by force, but on the whole in faithful compliance with legally established rules. In this respect, it is important to realize that the means of production—that is to say, the entire productive capacity that is needed for producing consumer goods as well as additional capital goods—may legally be, and for the most part are, the private property of individuals.

For the sake of simplicity, in the discussion that follows I shall call “workers” all those who do not share in the ownership of the means of production—although this does not quite correspond to the customary use of the term. The owner of the means of production is in a position to purchase the labor power of the worker. By using the means of production, the worker produces new goods which become the property of the capitalist. The essential point about this process is the relation between what the worker produces and what he is paid, both measured in terms of real value. Insofar as the labor contract is “free,” what the worker receives is determined not by the real value of the goods he produces, but by his minimum needs and by the capitalists’ requirements for labor power in relation to the number of workers competing for jobs. It is important to understand that even in theory the payment of the worker is not determined by the value of his product.

Private capital tends to become concentrated in few hands, partly because of competition among the capitalists, and partly because technological development and the increasing division of labor encourage the formation of larger units of production at the expense of smaller ones. The result of these developments is an oligarchy of private capital the enormous power of which cannot be effectively checked even by a democratically organized political society. This is true since the members of legislative bodies are selected by political parties, largely financed or otherwise influenced by private capitalists who, for all practical purposes, separate the electorate from the legislature. The consequence is that the representatives of the people do not in fact sufficiently protect the interests of the underprivileged sections of the population. Moreover, under existing conditions, private capitalists inevitably control, directly or indirectly, the main sources of information (press, radio, education). It is thus extremely difficult, and indeed in most cases quite impossible, for the individual citizen to come to objective conclusions and to make intelligent use of his political rights.

The situation prevailing in an economy based on the private ownership of capital is thus characterized by two main principles: first, means of production (capital) are privately owned and the owners dispose of them as they see fit; second, the labor contract is free. Of course, there is no such thing as a pure capitalist society in this sense. In particular, it should be noted that the workers, through long and bitter political struggles, have succeeded in securing a somewhat improved form of the “free labor contract” for certain categories of workers. But taken as a whole, the present day economy does not differ much from “pure” capitalism.

Production is carried on for profit, not for use. There is no provision that all those able and willing to work will always be in a position to find employment; an “army of unemployed” almost always exists. The worker is constantly in fear of losing his job. Since unemployed and poorly paid workers do not provide a profitable market, the production of consumers’ goods is restricted, and great hardship is the consequence. Technological progress frequently results in more unemployment rather than in an easing of the burden of work for all. The profit motive, in conjunction with competition among capitalists, is responsible for an instability in the accumulation and utilization of capital which leads to increasingly severe depressions. Unlimited competition leads to a huge waste of labor, and to that crippling of the social consciousness of individuals which I mentioned before.

This crippling of individuals I consider the worst evil of capitalism. Our whole educational system suffers from this evil. An exaggerated competitive attitude is inculcated into the student, who is trained to worship acquisitive success as a preparation for his future career.

I am convinced there is only one way to eliminate these grave evils, namely through the establishment of a socialist economy, accompanied by an educational system which would be oriented toward social goals. In such an economy, the means of production are owned by society itself and are utilized in a planned fashion. A planned economy, which adjusts production to the needs of the community, would distribute the work to be done among all those able to work and would guarantee a livelihood to every man, woman, and child. The education of the individual, in addition to promoting his own innate abilities, would attempt to develop in him a sense of responsibility for his fellow men in place of the glorification of power and success in our present society.

Nevertheless, it is necessary to remember that a planned economy is not yet socialism. A planned economy as such may be accompanied by the complete enslavement of the individual. The achievement of socialism requires the solution of some extremely difficult socio-political problems: how is it possible, in view of the far-reaching centralization of political and economic power, to prevent bureaucracy from becoming all-powerful and overweening? How can the rights of the individual be protected and therewith a democratic counterweight to the power of bureaucracy be assured?

Clarity about the aims and problems of socialism is of greatest significance in our age of transition. Since, under present circumstances, free and unhindered discussion of these problems has come under a powerful taboo, I consider the foundation of this magazine to be an important public service.

https://monthlyreview.org/2009/05/01/why-socialism/

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

- By Gus Leonisky at 5 Feb 2025 - 5:10pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

beauty of a cloud....

Rosa Luxemburg’s cheerfulness in times of war

Bitter year-end reflections, gloomy forecasts and good intentions … Whining is ridiculous

by Felix Schneider

In the midst of World War I, Rosa Luxemburg writes to her friend Luise Kautskyon 26 January 1917:

“You must have lost your desire for music, as well as for everything else, for quite a while now. Your mind is filled with worries about the faltering course of world history, and your heart is full of sighs over the wretchedness of Scheidemann and comrades1 and everyone who writes to me similarly groans and sighs. I find nothing more ridiculous than this. Do you not realise that the universal Dalles [a Yiddish word for hardships] are too vast to be moaned over?

I may find myself troubled when little Mimi2 falls ill or when something ails you. But when the entire world seems to be unravelling, I simply strive to understand what has occurred and why. Once I have fulfilled my duty, I remain composed and in good spirits. Ultra posse nemo obligatur.3 Moreover, I still have all the things that delight me: music, painting, the clouds, springtime botanizing, good books, Mimi, you, and much more. In short, I am immensely rich and intend to remain so until the end. This complete immersion in the sorrow of the day is utterly incomprehensible and unbearable to me.

Consider, for example, how Goethe stood above the fray with cool composure. Just think of what he had to endure: the Great French Revolution, which, when viewed up close, must have seemed like a bloody and entirely pointless farce, and then from 1793 to 1815, an uninterrupted chain of wars, during which the world appeared as a madhouse let loose. Yet, how calmly, with such intellectual equilibrium, he pursued his studies on the Metamorphosis of Plants, on the Theory of Colours, on a thousand different matters.

I do not demand that you compose poetry like Goethe, but his philosophy of life – the universality of interests, the inner harmony – can be adopted or at least aspired to by anyone. And if you suggest that Goethe was not a political fighter, I would argue that a true fighter must strive to rise above the mundane, lest they find themselves stuck with their nose in every trivial detail – though indeed, I refer to a fighter of grander vision, not the kind of weathervane ‘great men’ from your round table4 who recently sent me a postcard here. […]”5

Under Detention

Rosa Luxemburg (born 1871 in Russian Poland) penned the letter, from which the above excerpt is taken, while incarcerated in a German prison. Following the completion of her sentence, stemming from her socialist and pacifist activities, she was not released but was instead placed in ‘protective military custody’. Consequently, she was initially held in the police prison at Alexanderplatz in Berlin and subsequently at the women’s prison on Barnimstrasse. Luxemburg was eventually imprisoned in the fortress of Wronke in Posen, where she composed the lengthy letter to ‘Lulu, beloved!’ She was later transferred to Breslau, from where she was eventually liberated during the November Revolution of 1918. Tragically, she had approximately two months remaining to live until her assassination by members of the Freikorps.

Defence

Luxemburg, known for her steadfast adherence to principles, had, of her own volition, relinquished a conventional bourgeois career, a life of comfort, and even her physical freedom. Yet, it is ironically this very same person who now stands in defence of personal, private happiness. How does one reconcile this apparent contradiction?

To some extent, Luxemburg’s discourse reflects an internal dialogue, an effort to ward off her own struggles, as she was no stranger to bouts of depression and suicidal thoughts. In the same letter to Luise Kautsky, she refers to a “brief period of miserable cowardice,” where she felt “tiny and weak,” yearning desperately for “a heartfelt, warm letter” from her circle of friends. Her anticipation was in vain. “Thus, as always, I picked myself up again on my own, and it is just as well,” she writes.6

Proportions

Anyone interpreting this quoted letter merely as an opposition to dark spiritual forces would be underestimating Luxemburg. The focal point seems to be the sentence: “Don’t you understand that the general Dalles is far too immense to merely groan about it?” The Yiddish word “Dalles” signifies hardship, misery, catastrophe, and may serve as a reminder, perhaps unconscious, of the Jewish imperative to improve the world to hasten the arrival of the Messiah. This sentence undoubtedly implies a conception of proportionality, in which vast general and societal problems stand in contrast to the smallness of the individual. To us today, heavily influenced by narcissism, this notion might seem antiquated. For Luxemburg, it was founded on a belief that we have seemingly lost: a faith in “the objective logic of history, which tirelessly performs its work of enlightenment and differentiation.”7

Acting from inner freedom

Far from being outdated, Luxemburg’s stoic revolutionary ethos remains relevant.“ Above all,” she writes, “one must live at all times as a complete human being.” For Luxemburg, being completely human means also to be “resolute, clear, and cheerful.” The cheerfulness frequently mentioned in her letters expresses an inner freedom, which is the essential prerequisite for overcoming worries and fears, enabling one to move from paralysis to action. Here, being political and being human are inseparable. Cheerfulness, perspective, and sovereignty in the face of fate enable a person to intervene and act decisively at critical moments. One must, as Luxemburg suggests, be able to cast aside one’s life and simultaneously delight in the beauty of a cloud. •

https://www.zeit-fragen.ch/en/archives/2025/nr-2-21-januar-2025/rosa-luxemburgs-heiterkeit-in-kriegszeiten

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.