Search

Recent comments

- naked.....

8 hours 18 min ago - darkness....

8 hours 41 min ago - 2019 clean up before the storm....

14 hours 1 min ago - to death....

14 hours 40 min ago - noise....

14 hours 47 min ago - loser....

17 hours 27 min ago - relatively....

17 hours 49 min ago - eternally....

17 hours 54 min ago - success....

1 day 4 hours ago - seriously....

1 day 7 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

the interest of why you are getting poorer....

As the evidence of a slowing Australian economy mounts, Governor Michele Bullock quietly told journalists the RBA wants Australians to be poorer. Nobody seemed to notice except Michael Pascoe.

The problem with reporting a speech by the Reserve Bank Governor is that everyone tends to run the most obvious angle – “some people will have to sell their houses!” – or the preferred political angle – “RBA v Chalmers fight!” – as no journalist wants to be seen as missing the day’s big headline.

Unfortunately, this means the main news can be missed, and something that is not news and is entirely obvious – that some people have to sell their houses – dominates coverage.

That is what happened last week when Governor Bullock delivered the annual Anika Foundation speech and took questions. She made two important statements that nobody seemed to pick up and a third that only one journalist reported.

For mine, the real headline was that the RBA wants Australians to be poorer; to have a lower standard of living than they currently have. Think about that – average Australian living standards have been going backwards for two years, but the RBA thinks they’re still too high and wants them down.

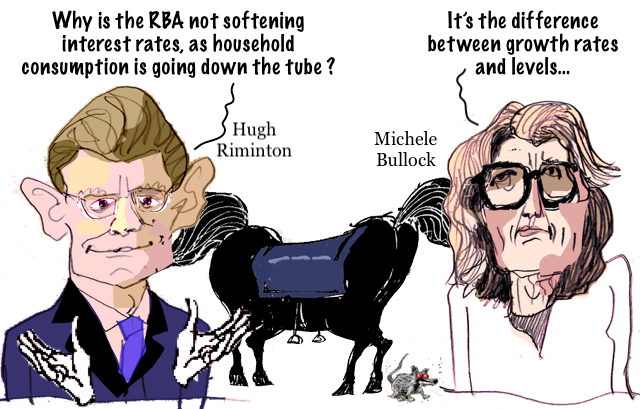

That is what follows from the Governor’s answer to a question about the preceding day’s pitiful GDP growth numbers – COVID aside, the weakest growth since the early 1990s recession. Hugh Riminton asked why the bank wasn’t softening its interest rate predictions, given that household consumption had come in significantly lower than the RBA forecast.

“In simple terms, Hugh, it’s the difference between growth rates and levels,” Ms Bullock replied.

Get it? To translate into English: Sure growth is miserable, negative on a per capita basis, but the level of consumption is still too high. We want you to have less, to be poorer. Or, in the Governor’s own words:

“It’s true that the growth rate of GDP has slowed. GDP itself was around where we forecast it would be, but the components were a little different. Consumption was a little softer. However, part of monetary policy’s job has been to try and slow the growth of the economy because the level of demand for goods and services in the economy is higher than the ability of the economy to supply those goods and services.

“So there’s still a gap there. So even though it’s slowing, we still have this gap. Part of that is because the supply side of the economy isn’t performing as well and productivity is part of that. Part of it is that demand was so strong coming out of the pandemic that its level is still above the ability of the economy to supply the goods and services.

“That’s why inflation is still there. So I understand why people would think that as things are slowing, that should be a reason to lower interest rates.

But we need to see the results in inflation before we can do that.

It’s about demand, not growth

There was that “level” thing again – the bank doesn’t care if growth is slow. It wouldn’t care if it was negative. It wants us to shrink our demand.

People who aren’t monetary hawks chanting “lift rates!” will see some of the obvious problems with this RBA policy.

Key factors in our “sticky” inflation aren’t or are barely influenced by interest rates – e.g. insurance premiums and health costs – but the RBA tightens policy anyway. (And, yes, policy is still tightening – the RBA says the last rate rise way back in November is still working its way through the system.)

Furthermore, that more restrictive monetary policy is making some key aspects of the alleged demand/supply imbalance worse, most obviously rent and housing costs. While trying to kill demand, the RBA also is wounding supply, keeping inflation “sticky”.

Ms Bullock’s predecessor, Philip Lowe, addressed that very point two years ago in what might have been his best speech. Life had been easier for central bankers when inflation was all about excess demand.

“Life is more complicated in a world of supply shocks,” Dr Lowe said.

“An adverse supply shock increases inflation and reduces output and employment. Higher inflation calls for higher interest rates but lower output, and fewer jobs call for lower interest rates. It is likely that we will have to deal with this tension more frequently in the future.”

Translation:

When a supply shock increases inflation too much, lifting interest rates can just make it worse.

A poor ‘solution’The current RBA management just wants you to be poorer.

Governor Bullock’s other overlooked admission was in answer to a question that was aimed at pushing the “government spending is to blame for inflation” line, which she dismissed by saying:

“Government spending is not actually the main game here. I think as we saw in the National Accounts yesterday, consumption is really weak. We are looking for a recovery in consumption but if that doesn’t occur, then that’s actually going to be a really important piece of information and it’s also going to be really important for the inflation outcomes. I think basically we should be focusing on the breadth of what’s happening in the economy, demand as in total demand and not focusing on individual components and thinking about what that means for the inflationary pressures in the economy.”

See that? While wanting a lower level of demand, the RBA is expecting consumption to increase. The RBA’s hawkish promise of no interest rate cuts this year appears to be based on its guess/bet that the tax cuts were going to bring consumers out spending.

the spendathon isn’t happening

Not only did the RBA woefully overestimate consumption in the June quarter, it shows no understanding of battered consumer psychology now. As the mounting data continues to show, the spendathon isn’t happening. Memo RBA: that’s “a really important piece of information.”

Turns out economists searching for meaning in the entrails of historical graphs are useless at divining “the vibe”. Time to hire some psychologists instead.

The third insightBullocks’ Anika Foundation speech presented a third mainly overlooked insight. The Guardian’s Peter Hannam asked a good question about the RBA’s quarterly forecasts being made on the basis of what the money market is betting will happen to interest rates, rather than what the RBA thinks (or actually knows) it will do. Bit silly when you think about it.

Mr Hannam wondered if the bank also ran through its models its own idea of where interest rates would be, rather than the money market’s guess, and what that meant for unemployment.

According to the quarterly statement on monetary policy, the bank’s model computes that if rates are cut this year (the money market’s bet), inflation will stay too high for too long – the trimmed mean measure is 3.1% for this financial year despite unemployment rising to 4.4%.

If this monetary policy thingy works then, it looks a fair bet that feeding higher rates for longer into the model should predict higher unemployment and lower inflation than what was published.

Ms Bullock answered that the RBA “can do that exercise” but professed no knowledge of what the numbers might be.

It looked to me like she may have wanted to dodge the implications of the question. I would be disappointed with the lack of intellectual curiosity in the bank, as I was when it said it never modelled the inflationary impact of tax cuts if the board wasn’t fiddling with the rangefinder on the only tool it has.

Peter Hannam was the only journalist to record that point and then did it modestly at the end of his column.

So, tying the three overlooked strands together, our central bank wants us to be poorer, fears we poorer consumers will start splashing money around sometime soon, and actually believes the unemployment rate will be higher and inflation will be battered down quicker than it officially forecasts.

That’s all more important than stating the obvious that people sell their houses when they can’t service their mortgage.

- By Gus Leonisky at 12 Sep 2024 - 4:49am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

grumpy club....

THE OUTDOOR DUNNY UNDER THE MOONLIGHT IS A REMINDER OF THE BEAUTY OF THE DEMANDS OF BEING COMFORTABLY ALIVE…

IN ONE’S SELF-INSIGNIFICANCE, SOME PEOPLE EXPERIENCE LATE-LIFE CRISIS AS ONE REALISES THAT OUR ALLOCATED DAYS ARE DIMINISHING. THIS WAS THE PROBLEM FOR ONE OF MY FRIENDS, RECENTLY. HE DID NOT WANT TO GO. HE DID NOT WANT TO DIE. BARELY 70, HIS BODY, CANCER RIDDLED, KILLED HIM.

SO, UNDER THIS LIGHT, GUS PONDERS MARK BEESON’S WISH TO OBLITERATE HIMSELF SOON RATHER THAN NOW…

NO MATTER IF WE LIVE OR NOT, NO MATTER IF WE SATIRISE STUFF OR NOT, THE REALITY IS THAT NOTHING MATTERS FOR THE BRAVE ATHEIST AS THERE WILL BE MORE MORONS WHO VIE FOR RULING THE PLANET, ONE WAY OR THE OTHER, LIKE TRUMP OR KAMALA… THEY WILL BLOW US UP, REALLY OR FIGURATIVELY, BEFORE WE CAN TREAT OURSELF TO OUR LAST BINGE…

ONE NEEDS A MASSIVE DOSE OF SELF-CONTAMINATION IN HUBRIS TO BELIEVE ONE CAN LEAD SS HUMANITY/ENTERPRISE WITH A BETTER ZOOT SUIT THAN ANYONE ELSE, FOR WHOM THE ADORING/SELF-INDULGENT PUBLIC OF POLARISED BLIND MONKEYOLOGISTS VOTE FOR.

SO MY RELATIVE MESSAGE TO BEESON IS HANG IN THERE AS LONG AS POSSIBLE — AND TAKE AS MUCH MORPHINE AS WHAT WON’T KILL YOU, IF PAIN PERSISTS…

-----------------------

Mark Beeson

Mark Beeson is an Adjunct Professor at the University of Technology Sydney and Griffith University. His latest book is Environmental Anarchy? International Relations Theory and Practice in the Anthropocene, (Bristol University Press: 2021) He has also written Environmental Populism: The Politics of Survival; in the Anthropocene Palgrave 2019....:

I’m thinking of calling it a day. Don’t be alarmed. I’m not planning to do so for two or three years, and this definitely isn’t the proverbial “cry for help”. Even at this seemingly late stage of planetary evolution, I don’t have too much to complain about. On the contrary, my biggest recent problem was deciding which Scandinavian country to visit as part of a (non-Australian) taxpayer-funded jaunt to Florence.

And yet, after much dispassionate contemplation, I can’t really think of any more useful contribution I could offer to the rest of humanity than making a slightly earlier exit than I might by letting nature take its course. I realise that even broaching such a subject will induce apoplexy and/or consternation among many readers as suicide remains one of the few taboos in the contemporary world, but it’s arguably a discussion we ought to have. Let me explain.

I have had an unbelievably fortunate and interesting life. Just being a baby boomer meant I was part of a uniquely lucky generation who, in the affluent West, at least, enjoyed unprecedented opportunities, living standards and freedoms that many young people today cannot imagine.

We generally didn’t have to fight in wars or worry about environmental catastrophe, and we usually enjoyed subsidised higher educations and health care. Most of us were able to buy properties before they became too expensive to contemplate. Indeed, many of my generation bought several and rent them to impoverished youngsters.

Although I fret about the future of young people in this country, and especially in the Global South, personally I’ve not got much to complain about. True, I’m 72 and my operating system isn’t what it used to be, but I’m still pretty fit, healthy, and capable of taking planet-destroying trips around the world at other people’s expense. Indeed, despite endlessly banging on about the environmental crisis, I’ve spent an embarrassing amount of time making rather self-indulgent trips to conferences and “must see” exotic locations.

But even if you’re passing over what Donald Trump sensitively described as “shit hole” countries at 40,000 feet, it’s difficult to be completely unaware of what’s going on in the lives of the 80% of the world’s population who have never been on a plane. Even for those not experiencing conflict, flood, famine or persistent poverty, life could hardly be more different or lacking in opportunity. Little wonder so many flee to the hoped-for safety of the Global North.

Yet even though I’m fortunate enough to live in a fabulously wealthy country, I’m not comfortable about the idea of my fellow taxpayers forking out for exotic medical interventions on my behalf, especially as they will probably only result in me watching daytime TV in an old people’s home for a couple more years.

Given that I’m unlikely to do anything noteworthy or that I haven’t done before at this stage of the proceedings, and that general decline is inevitable, why not do something useful with my surprising, by global standards, wealth and good fortune? As I don’t have children or dependents and much of a stake in the future, this is not such an outlandish question. Nor will my very agreeable friends be unable to come to terms with my absence, or even surprised about my early exit either, I suspect.

So, here’s the plan. In a couple of years’ time, I shall make a very civilised, painless (it’s really not that difficult or unpleasant), premeditated exit and leave nearly all I have to Médecins Sans Frontières. I’m already an enthusiastic contributor, but here’s my chance to do something really useful and support the saintly souls who really do make a difference in the most appalling circumstances. I can’t do anything useful in Gaza, but luckily I can outsource my responsibility to people who can.

I’m not suggesting that anyone else should follow my example and would be (theoretically) surprised if they did. But there are worse things that could happen in the world than rich people giving some of their money away. As a confirmed agnostic, I have no idea what goes on in the “post-death space”, but it’s going to happen soon anyway whatever it is, so a couple of years here or there won’t make much difference. As it is, I’ve already exceeded the Biblical allocation of three score and ten.

True, three score and fifteen doesn’t have quite the same ring to it, but it’s still more than many people get. The average checkout time in Chad, for example, is still only 55, and it’s hard to imagine life was full of endless opportunities for personal growth and self-indulgence while it lasted. There really is something to be said for quitting while you’re ahead and can still do something useful. Indeed, if there’s one thing the planet is not short of its grumpy old men. Except in Chad, obviously.

https://johnmenadue.com/taking-one-for-the-team/

READ FROM TOP

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

inflation/deflation....

When should we expect interest rates to fall? By Michael KeatingThe Reserve Bank has explicitly warned against any expectation that interest rates will start to fall soon. On the other hand, the Treasurer recently claimed that the Reserve Bank is smashing the economy, implying that interest rates should fall soon. Who is right?

Interest rates have risen exceptionally rapidly over the last two years, with the Reserve Bank’s cash rate increasing 13 times between May 2022 and November 2023 from 0.1% to 4.35%. This, of course, was in response to an unacceptable rate of inflation which peaked at 7.8% over the four quarters ending in December 2022. Now inflation is falling in response to the increase in interest rates, and the latest data show inflation increasing at an annual rate of 3.8% over the four quarters ending in June 2024, while the Reserve Bank’s preferred measure of underlying inflation — the trimmed mean — increased by 3.9% over that year.

Although the inflation rate is still running above the Reserve Bank’s target range of 2-3%, the critical question now being asked is when will interest rates start to come down?

The Reserve Bank, for its part, has stated that it does not expect inflation to be back in its target range until the end of 2025 and to only approach the midpoint in 2026. Based on these forecasts, it has counselled “it is premature to be thinking about rate cuts” and implied that we should not expect any cut in interest rates before sometime in the first half of next year at the earliest.

On the other hand, last week Treasurer Jim Chalmers argued that the Reserve Bank was “smashing” the economy, with the implication that interest rates should start to come down sooner rather than later, and probably this calendar year. Also, as Ian McAuley pointed out in his Weekly Roundup for 3 August, these annual inflation rates that the RBA is relying on are heavily influenced by the rate of inflation six months ago. If instead we take a three-month moving average of the monthly CPI data then inflation is already back down in the RBA’s comfort zone.

Chalmers was, as usual, immediately attacked by the Opposition and its media supporters, but that begs the question: what would they do instead? Peter Dutton and Angus Taylor refer blandly to how major cuts in public spending are necessary if we want to reduce inflation sooner while relying less on interest rate increases. In principle, lower public spending is a legitimate way to reduce inflation, but the Opposition never spells out where and how it would make these cuts, let alone what would be their impact on our well-being.

The question to be explored further in this article is, therefore, who is right and when and how interest rates should come down.

The Reserve Bank’s position: how strong are their arguments?

As the RBA itself has acknowledged many times, there is a narrow path if we are to bring inflation down while avoiding a recession.

However, as the RBA sees it, inflation is still too high, and on the other hand the economy is still continuing to grow. Demand is continuing to put upward pressure on inflation, according to an RBA Assistant Governor, Sarah Hunter, when she appeared in front of a Senate Committee a couple of weeks ago. Nevertheless, GDP only grew by 1.0% over the last year and GDP per capita has been falling for the last six quarters.

The other critical indicator that guides the RBA is the unemployment rate, and more generally the strength of the labour market. As Governor Michelle Bullock put it in a speech last week, “the Board is looking to strike an appropriate balance between the RBA’s inflation and full employment objectives.”

However, when considering that balance, the RBA is still heavily influenced by the experience of inflation back in the 1970s and 1980s. As Bullock reminded us in her speech, inflation as measured by the CPI, reached 17.7% in March 1975 and it remained around 10% for the rest of the 1970s and early 1980s. Furthermore, expectations about future inflation took off, resulting in a wage-price spiral which made it very difficult to bring inflation back down without a recession.

In response to that experience, for a long time RBA monetary policy decisions relied heavily on the Phillips curve which purported to show the relationship between the level of unemployment and the rate of inflation of both wages and prices. Thus, the Bank targeted the NAIRU which was defined as the rate of unemployment consistent with achieving its inflation target.

However, the RBA has been slow to recognise and appreciate how changes in the labour market can affect the NAIRU and the shape of the Phillips curve. Consequently, the RBA persistently overestimated annual wage growth by about 1 percentage point every year between 2011 and 2019. Nevertheless, throughout that period the Bank staff continued to suggest that the NAIRU had changed little and was still close to 5%. Then in mid-2019 the Bank announced that it had revised its estimate of the NAIRU to 4½%.

Today the Bank no longer talks about the NAIRU specifically, but it seems very likely it still thinks unemployment is, if anything, too low and needs to rise if inflation is to be brought back down into its target range of 2-3%. For example, in her speech last week, Bullock stated that “the labour market remains relatively tight”, whereas it is arguable that it has eased. Also, it is likely that the NAIRU has fallen further below 4½% and that labour demand is already now too low to sustain the present inflation rate.

The Labor Government’s position

Contrary to the Opposition’s criticisms, the government’s fiscal policy has broadly complemented the RBA’s efforts to tighten monetary policy, thus reducing demand and helping to bring inflation down. In both its first two budgets for 2022-23 and 2023-24 the Albanese Government produced surpluses, the first since 2007-08.

Admittedly, the current Budget for 2024-25 is projected to record an underlying cash deficit equal to 1.0% of GDP, but that is quite a small turnaround equivalent to 1.3% of GDP. Also, although total government spending is forecast to increase significantly in 2025-25 by 4.5% in real terms, that comes after a couple of years of falls, and government payments are still less as a share of GDP than in the last two years of the Morrison Government.

Most importantly, Labor’s new spending has largely been directed to repairing the damage done to many government services ranging across health, education, aged and child care, foreign affairs and the public services by the Morrison Government’s deliberate attempt to save money by underfunding government responsibilities. Even now, it is arguable that more money is needed to restore adequate service delivery, but that would require extra revenue; something from which the Albanese Government has shied away.

Furthermore, without that extra government spending it is likely that the economy would already be in recession. The latest national accounts show that private consumption, which accounts for around 60% of aggregate demand, fell 0.2% in the last June quarter and, on a per capita basis, household consumption has declined for five of the last six quarters. Furthermore, household saving is now down to a very low 0.6% of income, much less than the peak of 24.1% reached during the COVID lockdowns, so it will be even harder to sustain household spending in future.

In addition, in response to the weak household demand, the volume of private business investment has also fallen in the last two quarters by 0.5% in the March quarter and 1.5% in the June quarter. In sum, without the increase in government spending, which contributed half a percentage point to GDP growth in the first half of 2024, the economy would be going backwards.

Similarly, over the four quarters ending in June 2024, the hours worked in the market sector fell by 0.7%, and the small increase of 0.5% in the total hours worked across the economy was entirely accounted for by the substantial increase in non-market sector jobs, further underlining that without the restoration of government services, Australia would be in recession.

Also, it should be noted that much of the additional government spending in this year’s budget is deliberately aimed at restraining the impact of inflation. The additional assistance for rents, electricity bills, cheaper medicines and childcare are all aimed at reducing the recorded rate of inflation as well as providing cost-of-living relief. For example, Treasury estimates that the energy bill relief and the additional rent assistance will directly reduce inflation by half a percentage point in 2024-25 and without adding to broader inflationary pressures.

Conclusion

Although inflation is not yet back in the RBA’s target range, it is coming down, while the economy is already tottering on the edge of a recession. Furthermore, there are inevitably lags before any change in monetary policy takes effect, and so we can expect inflation to keep falling.

Even the RBA does not seem to envisage that any further increase in interest rates will be necessary. Its fear is that so long as inflation remains too high, there is an increasing risk that expectations about future inflation will change, leading to a wage-price spiral as experienced in the 1970s.

But as Jerome Powell, the chairman of the US Federal Reserve has noted, inflationary expectations have not taken off in the US and the US is therefor starting to cut its interest rates. Much the same is true here in Australia. Labour market institutions have change enormously since the 1970s and early 1980s, and, just as in the US, Australian inflation expectations have remained anchored.

Thus, it is time to start cutting interest rates here as well. Indeed, financial markets have already started pricing in one interest rate cut by Christmas and a total of three by May. Any delay will increase the risk of recession without changing the inflation pathway much at all.

In sum, the RBA should start cutting interest rates this year and the sooner the better. However, it is understandable that the RBA might want to wait until its December Board meeting as the next National Accounts will be released just before that meeting allowing the Board to consider the latest data on the economy before changing course. But the balance of risks strongly suggest that the RBA should wait no longer than December to start bringing interest rates down.

https://johnmenadue.com/when-should-we-expect-interest-rates-to-fall/

READ FROM TOP

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

sigh of relief ....

Ross Gittins

Dutton’s election campaign rout lets RBA off the hookReserve Bank governor Michele Bullock must be breathing a quiet sigh of relief now the Albanese Government has been triumphantly returned to office. If you can’t think why she should be relieved, you’re helping make my point.

There was something strange in all the accusations hurled at Labor for doing little or nothing to ease the great cost-of-living pain so many voters had suffered over the three years of its first term in office.

And that was? Never once did Peter Dutton mention the Reserve Bank. The tough state of the economy was 100% Labor’s fault. And never once did Anthony Albanese or Treasurer Jim Chalmers say what they could have: “Don’t blame us, it was the central bank wot dun it.”

“And there was nothing we could do to stop it doing what it did,” Labor didn’t say. “Had we tried to counter what the Reserve did in increasing mortgage interest rates by a massive 4.25 percentage points, it would just have raised rates even further.” (As every macroeconomist knows, such behaviour is dignified by the title “the monetary policy reaction function”.)

So Albo & Co did what the system required of them: they stood there and took all the abuse on their own chins. Since the Reserve was granted independence of the elected government in the mid-1990s, the deal between the elected government and the Reserve is that the Reserve says nothing about the government’s conduct of fiscal (budgetary) policy, and the government says nothing about interest rates.

Albanese’s quite unexpected landslide win will tempt many people to start rewriting history in favour of the victors. “Ah yes, Labor was never really in any bother and there was never much risk that all the cost-of-living pain could see it tossed out.”

Bollocks. Before the formal start of the campaign in late March, the polls showed there was a big chance Labor would be tossed out. The Coalition was ahead in the polls, and Peter Dutton’s personal approval rating was high.

It was only as the five-week campaign progressed, and voters got their first close look at Dutton and started listening to what he was saying, that the Coalition’s lead in the polls started sliding and voters’ comparison of him with Albanese started shifting in Albo’s favour.

Both sides knew from their research that the cost of living was the only issue voters wanted to know about. So both sides vowed to talk about little else. Labor stuck to that resolve, but Dutton couldn’t make himself do so.

The truth is, throughout his long career in politics, Dutton has shown little expertise or interest in the management of the macroeconomy. He’d been a copper, who saw his life’s vocation as to “protect and serve”. He was on about the threat to our security from abroad and the threat on our own streets. And, as the campaign progressed, that’s what he kept returning to.

He was the wrong person to be leading the Coalition at a time when economics was all that mattered. He had a powerful (though misleading) line asking people if they felt better off than they were three years ago, but failed to keep pushing it. This left Labor room to push its antidote: “Don’t worry, the worst is over, interest rates have started coming down, and soon everything will be back to normal.”

But what’s that got to do with the Reserve Bank? Just this: had the Coalition succeeded in getting Labor sacked, Labor would rightly have blamed the Reserve’s tardiness in cutting interest rates for that sacking, and its side of politics would have gone for at least a decade seeing the central bank as the enemy.

But don’t think the Coalition would have loved the Reserve forever. It would have thought: “If those blasted bureaucrats can trip up Labor, next time they might trip us up”. Get it? Both sides would have been looking for ways to clip the Reserve’s wings.

Two points. First, central bank independence and democracy make awkward bedfellows. They mean the Reserve has all care and no responsibility. Much as they may want to, the voters can’t sack Michele Bullock. The only people voters can take the Reserve’s performance out on are members of the elected government.

Second, the post-pandemic price surge is the first big spike in inflation in the 30 years since the rich economies adopted the policy of handing over primacy in the day-to-day management of the economy to an independent central bank with an inflation target.

So, only now has this regime been stress-tested. This test has revealed how hard it is for a democratically elected government to carry the can for a central bank taking a seeming eternity to use higher interest rates to get the inflation rate back into the target zone.

The truth is, all the seeds of the inflation surge were sown before Labor was elected in May 2022. But Labor didn’t waste its breath trying to mount that argument. The retort would have been obvious: surely three years is long enough for any macroeconomic problem to be fixed?

Good point. When Labor took over, the annual inflation rate stood at 5.1%. By the end of 2022, it had peaked at 7.8%. But by this time last year — 15 months later — it was down to 3.6%. And now it’s back in the 2% to 3% target range.

So, with consumer spending almost flat, the past year has seen inflation do what it could always have been expected to do: keep falling back to target. So why did the Reserve start cutting the official interest rate only in February?

The first rule of using interest rates to manage demand (spending in the economy) is that, because rate changes affect demand with a “long and variable” delay, you don’t wait until inflation reaches the target before you start cutting rates.

But the Reserve has ignored this rule because of its fear of a wage explosion that was never likely to happen. Its “blunt instrument” has hurt voters with mortgages more than was needed. Fortunately for the Reserve, however, its mismanagement hasn’t got an innocent government kicked out.

Republished from the Sydney Morning Herald, 5 May 2025

https://johnmenadue.com/post/2025/05/duttons-election-campaign-rout-lets-rba-off-the-hook/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.