Search

Recent comments

- naked.....

3 hours 24 min ago - darkness....

3 hours 47 min ago - 2019 clean up before the storm....

9 hours 7 min ago - to death....

9 hours 46 min ago - noise....

9 hours 53 min ago - loser....

12 hours 33 min ago - relatively....

12 hours 55 min ago - eternally....

13 hours 1 min ago - success....

23 hours 29 min ago - seriously....

1 day 2 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

when the past was less reactionary shitty than the present.....

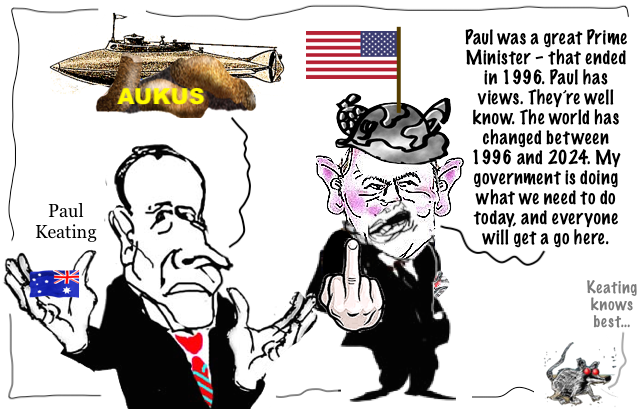

When the former Prime Minister, Paul Keating, recently claimed that Australia was losing its “strategic autonomy” and turning into “the 51st State of the United States”, the current Prime Minister froze in the headlights.

Possibly caught before his staff could give him a few dot points, Albanese said “Paul was a great Prime Minister – that ended in 1996. Paul has views. They’re well know. The world has changed between 1996 and 2024. My government is doing what we need to do today, and everyone will get a go here.”

A timid PM, frozen in the glare of the Keating headlights By Paddy Gourley

These forlorn sentiments attracted an eyewatering riposte from Keating (Pearls and Irritations 10 August 2024) that can only be augmented by modest embroidery.

Albanese praises Keating with unconvincing sincerity. He illogically implies that the value of his predecessor’s views expired in 1996 when he ceased to be the Prime Minister. He doesn’t engage with Keating’s comments or try to justify his own position – he just changes the subject. And his claim that everyone “will get a go here” is much at odds with the smothering secrecy with which the AUKUS, for example, is embalmed.

If Albanese’s behaviour in this case was atypical, it might be possible to keep disappointment within reasonable bounds. Unfortunately before and after he became Prime Minister Albanese has been inept at taking the community into his confidence about policy via clear, plain-speaking advocacy.

As is notoriously well know, when the Morrison government sprung the AUKUS deal on Albanese, he rolled over within a couple of hours. Major policy must be treated with much more respect than that. Albanese should have said “Hang on. I want to be fully informed on this massive deal and I want the time for the ALP to go through proper due process before it takes a position and that time will be after the election when the people have had a chance to see it and when, if I win, I will have the benefit of full advice from the public service and the military.” He didn’t and the AUKUS albatross is now around the necks of all Australians.

The international editor of the Australian Financial Review, James Curran, is right when he complains about the Albanese government’s “persistent failures in communication, an unwillingness to take the public into its confidence and the inability to explain the basic strategic purposes of why Australia seeks to acquire nuclear powered submarines.”

As Opposition Leader, Albanese also rolled over on the Morrison government’s tax cuts. That is, in the lead up to the last election, an ALP leader was unprepared to run the case against tax cuts that essentially would have transferred wealth from the less well off to the more wealthy. Then in government Albanese cancelled the Morrison tax cuts, gained little political credit for doing so and whacked a discount on the reliability of his word.

Then there’s the Voice referendum. There is a case to be made that it could only have succeeded with the support of the Liberal-National parties. Evidence of Albanese’s attempts to get them on side before he committed to the referendum are not thick on the ground. Sure, he put a lot of effort into the Voice campaign. Yet even then Albanese failed, in several major speeches, to make out the case, seemingly content to rest on repeated quips about “If not now, when?”

The so-called “Future Made in Australia” may well be an Albanese brainchild born of an idea that Australia should “make things”. It’s difficult to know what to make of this policy because again he’s made no convincing case for it. Meanwhile taxpaying funders of the program cannot be told of the expected internal rates of return on particular investments because of implausible claims of “commercial-in-confidence”. Albanese says “My government wants to reinvigorate Australia’s industrial base to create wealth and opportunity” but he doesn’t address the fact that as the country shed a good deal of its manufacturing industry it enjoyed a long period of continuous economic growth and prosperity.

If Albanese is weak on advocacy of policy particulars, he not so flash on overall strategy. His recent article in The Australian newspaper titled “Time for big, bold ideas: PM’s vision for the next decade” contained few “big ideas”, big, bold or otherwise. Instead, he treated readers to a numbing collage of platitudes – “Australia is the greatest country in the world.” “Australians are future shapers”. “Australians work hard and dream big”. “We stand at the dawn of what can and should be Australia’s decade.”

Citizens will not be properly engaged in government by such anaesthetising palaver – they’ll be alienated from it. Albanese should look to Keating’s example and speak to the citizenry in ways that grab their attention and make them think and participate more in public life.

As his prime ministership has matured, as it were, Albanese has been growingly criticised for timidity and a lack of policy ambition. These tickings-off are not entirely unfair although they seem to be more about symptoms of different problem – a struggle to grapple effectively with policy and explain it.

What’s plain is that Albanese is no Whitlam, Hawke, Keating or Gillard when it comes to policy. Yet if he is to be one of his “future shapers” of “Australia’s decade”, he needs to do a lot better. As the bottom of his hourglass rapidly fills with sand, he risks missing out on the chance to invert it.

https://johnmenadue.com/a-timid-pm-frozen-in-the-glare-of-the-keating-headlights/

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

- By Gus Leonisky at 14 Aug 2024 - 7:30am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

aukusings.....

BY Lorenzo Maria PACINI

With the current inappropriate foreign interference of the UK and the U.S. in Australia’s politics, it is likely that the country will be elected as the new sacrificial lamb in the macabre geopolitical ritual of the collective West.

On July 12-13, Australian Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister, Richard Marles visited the United Kingdom, to meet with the newly appointed UK Secretary of State for Defence, the Rt. Hon John Healet MP. The visit was official but the contents have not been divulgated. The main topic was the development and expansion of AUKUS.

Anti-China, anti-North Korea, anti-India

We should not be surprised: the AUKUS Treaty was signed on 15 September 2021 between the United Kingdom, the United States of America and Australia with the aim of enhancing the three countries’ military defence. The trilateral agreement focused on the development of nuclear-powered submarines and an increased presence in the Pacific, but also on the development of tools for hybrid warfare, with a focus on artificial intelligence, cyber warfare and long-range missiles, in tandem with the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing alliance that also includes New Zealand and Canada.

Why increase military engagement in the Pacific? The answer is simple. Consistent with classical maritime doctrine, the UK-U.S. bloc must dominate the seas to maintain its thalassocratic power. Anglo-American imperialism is entirely maritime. The Pacific is the sea ‘to the west’ of the U.S. and is the one that touches the Asian continent, interacting with the continental bloc of China and other tellurocratic countries. When the British Empire began its expansion, establishing control over the East Indies, it was clear from the outset that without the Pacific it would not be possible to maintain oceanic balance. After WWII, the U.S. also entered the game, positioning numerous military bases scattered among the islands of the Pacific Ocean, so as to create a ‘nuclear belt’ off China and South-East Asia, but also off South America, controlling the routes beyond the fire belt and those to Antarctica.

From a strategic point of view, the nuclear build-up is clearly aimed firstly at countering China, which is the most ‘dangerous’ power for Anglo-American interests in the Pacific – even though it is not a sea power and has never made maritime conquests; secondly, it becomes an instrument of restraint towards India, consistent with the need to control Rimland and prevent the strengthening of Eurasian alliances – and India, after all, has long been a British colony, so there is a desire for colonial revenge -; thirdly, but no less importantly, it is a provocation (or deterrence strategy) against North Korea, which has no declared maritime interests, but remains an atomic power that defines the North Pacific balance of power, with eyes on Japan and the U.S. continuously.

The AUKUS, then, in an anti-China, anti-India and anti-Korea key. This is the real purpose of the military alliance.

Remote deterrence as a strategic rationale.

The technology-sharing agreement with the United Kingdom and the United States will see eight nuclear-powered submarines (SSNs) in Australian service by 2050, an agreement that is in Australia’s interest because it enhances the country’s ability to deter war through nuclear deterrence. The Defence Strategic Review of 2023 explicitly assigns the Australian Defence Force a relatively new international role. The main reason for the acquisition and construction of SSNs in Australia is their powerful strategic effect, as they can provide the Australian Defence Force (ADF) with a superior regional capability. The AUKUS for Australia is the best offer: the benefits potentially – or so they say – outweigh the costs.

One wonders if the perception of constant threats from China, which itself is not militarily threatening to any adversary or enemy, is rather a political imposition – a real psy-op – by the Anglo-American establishment, with the aim of motivating Australia’s strategic engagement, opening up the possibility of another front for another proxy war.

The Commonwealth obeys

The Commonwealth countries can do nothing but obey and do what they were colonised to do, which is to serve the British crown indiscriminately. Marles’ trip to the UK is a mandatory stop to receive orders and agree on operational strategies.

It is clear that this is a division of labour with NATO: the Atlantic Alliance manages its ocean, the AUKUS takes the other.

In the meantime of the visit of Marles, there was a visit to the Clyde naval base in Scotland, where the Astute class submarine was demonstrated. The first three Australian officers completed their training on the nuclear reactor training course; also a report by the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) on the possible expansion of AUKUS was published.

As Marles stated, “The United Kingdom is one of our closest and most enduring partners. I look forward to working with Secretary Healey to progress initiatives which will serve to deepen our defence partnership now and into the future […] In an increasingly complex strategic environment, the United Kingdom remains a critical partner supporting the rules-based global order which benefits us all”.

The Federal Government is not keeping tabs on whether Australians are heading overseas to fight for foreign militaries, including for Russia, in what experts say could be a risk to national security. The Home Affairs Department and Australian Border Force have revealed they ‘do not track individuals travelling overseas intending to serve in foreign military services’, including the Russian defence force, in response to questions on notice from the last round of senate estimates. They said that while they were not aware of any Australian residents leaving to join the Russian military, they believed four had travelled to serve the Israeli Defence Force since October 7, but did not have an exact figure.

Australians have a long history of fighting for foreign militaries, and while it has never been tracked and is not illegal, one expert said not knowing who is engaging with militaries of countries such as Russia could pose security risks.

Making a projective analysis, it is not hard to imagine that Australia could become the next Ukraine for China. The American and British military presence in the region has significantly increased, the AUKUS is being strengthened, and simulations of conflict are likely to grow. It’s about creating a threat to China by using Australia, in the same way the U.S. used Ukraine against Russia.

Staying on the psychological level, it is probable that the undersea balance determines Australia’s psychological freedom. Or perhaps it’s just yet another deception.

Australia’s freedom of movement would be the first casualty of unrestricted submarine warfare, as happened in the Atlantic and the Pacific during the Second World War. But it would be wrong to think of this threat only in terms of the damage it could inflict on Australia’s navy in wartime. In some ways, the bigger risk is that this hypothetical threat deters Australia today from even contemplating the sorts of actions it would consider to be in the national interest. In a regional war, the balance would probably be determined not so much by Australia’s actual war power, but by American support, geographically closer than British support, but to do this it would have to make the Indo-Pacific contingency prevail, to the detriment of the European contingency, necessarily involving Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, Guam and the other small states under its influence.

Here another question arises: UK-U.S. are now only capable of provoking conflicts by involving strategic partners. On their own, they no longer have the real strategic, economic and political power to succeed.

With the current inappropriate foreign interference of the UK and the U.S. in Australia’s politics, it is likely that the country will be elected as the new sacrificial lamb in the macabre geopolitical ritual of the collective West.

https://strategic-culture.su/news/2024/08/15/aukus-ready-war/

READ FROM TOP

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

faukusing on aukus...

AUKUS: The worst defence and foreign policy decision our country has made

By Gareth Evans

Defence Minister Marles’s love for the the US is so dewy-eyed as to defy parody. Foreign Minister Wong is far more beady-eyed, and instinctively wary of over-commitment to America’s view of itself, but has been unwilling to rock the boat.

Politics played a significant part in the birth of AUKUS in Australia, and politics both here and in the US will play a crucial role in determining whether it lives or dies. That is so at least for its core submarine component, on which I will focus here: the second pillar of the agreement, relating to technical cooperation on multiple new fronts, is both much less clear in its scope and less obviously politically fraught.

On the Australian side, partisan political opportunism was a factor in the initiation of the submarine deal, bipartisan political support was a condition of US agreement to it, and maintenance of that bipartisan support into the future presumably will be a precondition of its continuance, at least when it comes to highly sensitive elements like the handover of three Virginia class submarines.

On the American side, it was perception of US strategic advantage that drove Washington’s agreement to the deal – best summarised by Kurt Campbell’s indiscreet observation that “we have them locked in now for the next 40 years” – rather than any domestic political considerations. But it remains the case that strong cross-party support in Congress will remain necessary for its complete delivery. And, at the even more critical Executive level, it cannot be assumed that the deal is now Trump-proof.

It is only in the UK that we can reasonably regard domestic politics to be irrelevant to AUKUS’s future. The deal is so obviously a gift to the national Treasury, and has so little impact on national defence and security interests (other than, perhaps, nurturing the delusion of some continuing British influence on world affairs East of Suez), that no one on any side of politics is ever likely to find it unpalatable.

In Australia, domestic politics have been a factor from the outset. While for the Morrison Government the primary driver of the AUKUS decision was, no doubt, the ideological passion of senior Coalition ministers for all things American, massaged by hugely influential advisers like Andrew Shearer, it is hard to deny political opportunism came a close second. Morrison was deeply conscious of the opportunity the deal presented to wedge the Labor opposition in the defence and security space, where the ALP has long been perceived, rightly or wrongly, as electorally vulnerable. That the nuclear dimension of the deal was bound to ruffle some feathers in Labor ranks was an added political attraction.

I was not critical at the time, and nor am I now, of the Opposition’s initial response in September 2021 when told at the last minute by Morrison of the imminent announcement of the deal he had struck with the US and UK, premised on Labor’s support. The political imperative was clear: had Labor been at all equivocal, 2022 would have been a khaki election, with Albanese depicted as undermining the alliance and undermining US commitment to the region. Moreover, the deal was at least prima facie defensible intellectually, with nuclear propulsion clearly superior in terms of speed, endurance and (for now, at least) detectability; and with nuclear proliferation and waste concerns being reasonably met by the lifetime-sealed character of the HEU propulsion units.

As I said publicly at the time, the Morrison Government was roundly to be criticised for comprehensively mishandling its breakup with the French, and there were very real questions still to be answered before the submarine deal was finally bedded down – in particular as to whether the force configuration proposed was really fully fit for Australia’s strategic purposes, and the implications of much greater enmeshment with the US military for the reality of our sovereign agency. But there would be plenty of time when Labor came into government for review, negotiation and readjustment.

What I am now critical of, and very critical, is that when Labor did come into office not many months later, in May 2022, it is clear no such serious review of the whole AUKUS deal ever took place. Crucial questions were never seriously addressed; clearly articulated answers to them have never been given by the Prime Minister, Defence Minister or anyone else; and the answers that are in fact emerging as further time passes are deeply troubling.

If a genuinely comprehensive and genuinely objective review were now to be initiated by the Albanese Government, it would, I believe, have no choice but to make these major findings.

One, there is zero certainty of the timely delivery of the eight AUKUS boats. We now know that both the US and UK have explicit opt-out rights. And even in the wholly unlikely event that everything falls smoothly into place in the whole vastly complex enterprise – Virginia transfers, British design and build, human resource availability, manageable costs and all the rest – we will be waiting 40 years for the last boat to arrive, posing real capability gap issues.

Two, even acknowledging the superior capability of SSNs, the final fleet size – if its purpose really is the defence of Australia – appears hardly fit for that purpose. Just how much intelligence gathering, or archipelagic chokepoint protection, or sea-lane protection, or even just “deterrence at a distance”, will be possible given usual operating constraints – which would here mean having only two boats deployable at any one time?

Three, the eye-watering cost of the AUKUS submarine program will make it very difficult, short of a dramatic increase in the defence share of GDP, with all that implies for other national priorities, to acquire the other capabilities we will need if we are to have any kind of self-reliant capacity in meeting an invasion threat were one ever to arise. Those capabilities include, in particular, state-of-the-art missiles, aircraft and drones, that are arguably even more critical than submarines for our defence in the event of such a crisis.

Four, the price now being demanded by the US for giving us access to its nuclear propulsion technology is, it is now becoming ever more clear, extraordinarily high. Not only the now open-ended expansion of Tindal as a US B52 base; not only the conversion of Stirling into a major base for a US Indian Ocean fleet, making Perth now join Pine Gap and the North West Cape – and increasingly likely, Tindal – as a nuclear target; not only the demand for what is now described not as the interoperability but the “interchangeability” of our submarine fleets. But also now the ever-clearer expectation on the US side that “integrated deterrence” means Australia will have no choice but to join the US in fighting any future war in which it chooses to engage anywhere in the Indo-Pacific, including in defence of Taiwan. It defies credibility to think that, in the absence of that last understanding, the Virginia transfers will ever proceed. The notion that we will retain any kind of sovereign agency in determining how all these assets are used, should serious tensions erupt, is a joke in bad taste. I have had personal ministerial experience of being a junior allied partner of the US in a hot conflict situation – the first Gulf War in 1991—and my recollections are not pretty.

Five, the purchase price we are now paying, for all its exorbitance, will never be enough to guarantee the absolute protective insurance that supporters of AUKUS think they are buying. ANZUS, it cannot be said too often, does not bind the US to defend us, even in the event of existential attack. And extended nuclear deterrence is as illusory for us as for ever other ally or partner believing itself to be sheltering under a US nuclear umbrella: the notion that the US would ever be prepared to run the risk of sacrificing Los Angeles for Tokyo or Seoul, let alone Perth, is and always has been nonsense. We can rely on military support if the US sees it in its own national interest to offer it, but not otherwise. Washington will no doubt shake a deterrent fist, and threaten and deliver retaliation, if its own assets on Australian soil are threatened or attacked, but that’s as far as our expectations should extend.

The bottom line in all of this was very presciently stated by Jean-Yves Le Drian, the then French foreign minister, in reacting to the Morrison decision in 2021: “The Australians place themselves entirely at the mercy of developments in American policy. I wish our Australian partner, who made the choice of security – justified by the escalation of tensions with China – to the detriment of sovereignty, will not discover later that it has sacrificed both.”

In the event that some of this political light did start to dawn on the Albanese Government and it did start to explore a Plan B, it would not be impossibly late to fundamentally change course yet again, with the most attractive option probably being – if Paris ever felt able to trust us again – the revival of the French contract. This not only provided for the delivery of 12 conventionally powered, but very capable boats, at a reasonable cost and within a reasonable time frame, but also explicitly allowed for a nuclear option to be pursued should we so desire. That change would involve more time and expense, and some new and serious complications in working out how to manage the nuclear refuelling and maintenance needs of an LEU system, but overall would involve much less baggage for us than continuing with the AUKUS program.

All that said, it has to be acknowledged that the odds of any fundamental change of course are now very long indeed. The only external event that could completely derail the AUKUS program and force such change would be the US making it clear that it was not going to give up any of its Virginias, because of the pressures on its own replacement program. But it’s hard to imagine even a Trump administration doing that, given the extraordinary favourability of the deal the US has wrung out of Australia – not only financially, but because for all practical purposes the Americans will be able to treat these boats as an extension of their own fleet.

The prospects of a political change of heart in Australia are even more problematic. On the part of the Coalition, in the absence of the reincarnation of Malcolm Turnbull, they are non-existent. And on the part of the ALP they are not much better. Defence Minister Marles’s love for the the US is so dewy-eyed as to defy parody. Foreign Minister Wong is far more beady-eyed, and instinctively wary of over-commitment to America’s view of itself, but has been unwilling to rock the boat. And Prime Minister Albanese is still preoccupied with avoiding being wedged as weak on security, has never given great attention to the complexities of foreign and defence policy and seems unlikely to change.

All this is rather depressing for those of us who have long nurtured the belief that Australia is a fiercely independent nation, ever more conscious of the need to engage constructively, creatively and sensitively with with our own Indo-Pacific neighbourhood, and with a vibrant multicultural society ever more representative of the world around us. A country which had come to terms at last with the reality that in the new century our geography matters much more than our Anglophone history. And a country which had put behind us the “fear of abandonment” which had been so central to our defence and diplomacy for so much of the last century: recognising, as Paul Keating continues to put it so articulately, that we need to find our security in Asia, not from Asia.

Australia’s no-holds-barred embrace of AUKUS is more likely than not to prove one of the worst defence and foreign policy decisions our country has made, not only putting at profound risk our sovereign independence, but generating more risk than reward for the very national security it promises to protect. I cannot imagine this decision being made by any of the Hawke-Keating Governments of which I was part, even when Kim Beazley was Defence Minister. Times have changed.

Panel presentation by Professor the Hon Gareth Evans to Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia Conference, AUKUS: Assumptions & Implications, Canberra, 16 August 2024

https://johnmenadue.com/aukus-one-of-the-worst-defence-and-foreign-policy-decisions-our-country-has-made/

READ FROM TOP

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.