Search

Recent comments

- 2019 clean up before the storm....

2 hours 56 min ago - to death....

3 hours 35 min ago - noise....

3 hours 42 min ago - loser....

6 hours 22 min ago - relatively....

6 hours 45 min ago - eternally....

6 hours 50 min ago - success....

17 hours 19 min ago - seriously....

20 hours 2 min ago - monsters.....

20 hours 10 min ago - people for the people....

20 hours 46 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

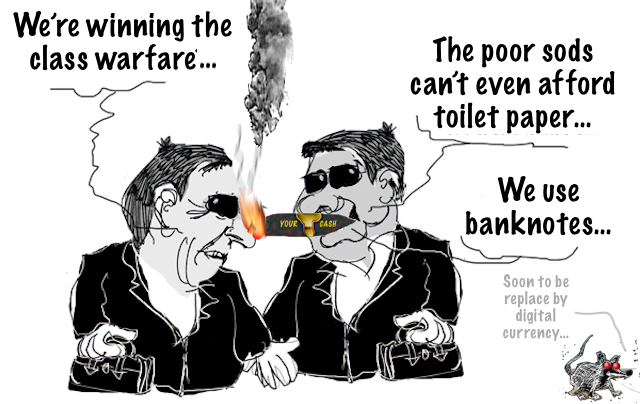

the rich are winning....

The billionaire once Warren Buffet famously said, “There’s class warfare, all right, but it’s my class, the rich class, that’s making war, and we’re winning.” New analysis released by Oxfam this week for International Workers’ Day shows concretely that since 2020, the rich class, as Buffet calls them, are winning big.

Global Inequality Has Skyrocketed Since the Pandemic

Over the past four years, capital owners reaped handsome profits at the expense of the working class and the Global South. The wealthy may have recovered from the pandemic — but the world’s poor are still suffering its economic effects.

Global dividend payments to rich shareholders grew on average fourteen times faster than worker pay in thirty-one countries, which together account for 81 percent of global GDP, between 2020 and 2023. Global corporate dividends are on course to beat an all-time high of $1.66 trillion reached last year. Payouts to rich shareholders jumped by 45 percent in real terms between 2020 and 2023, while workers’ wages rose by just 3 percent. The richest 1 percent, simply by owning stock, pocketed on average $9,000 in dividends in 2023 — it would take the average worker eight months to earn this much in wages.

This matters because as long as returns to capital increase faster than returns to work, the inequality crisis will grow. At the heart of our economy is a constant struggle between the owners — or capital, as it is known in economics — and the workers, or labor. The measure of progress, or the lack of it, is the extent to which the benefits of all those billions of hours of labor worked each day are accruing to workers and their families, driving greater equality, or the extent to which benefits are accruing to the owners of capital, driving greater inequality.

For the majority of people on our planet, the years since 2020 have been incredibly hard. The pandemic was a huge blow; millions were lost to the disease, and millions more were thrown into destitution as the world ground to a halt. The sharp increase in the cost of food and other essentials that followed in 2021 has become a grinding new reality for many families across the world as they try to buy oil, bread, or flour without knowing how many meals they will have to skip that day. I think of friends in Malawi, for example, where I used to live, who are struggling each day to stay afloat, or the millions in the UK who rely on food banks just to stave off hunger. Globally, poverty is still higher than it was in 2019. Inequality between the rich world and the Global South is growing for the first time in three decades.

But for the richest in our society, the owners of capital, the years since 2020 have really been good. Billionaires, of whom there are about three thousand worldwide, are some of the biggest shareholders. Seven out of ten of the world’s largest corporations have a billionaire CEO or a billionaire as their principal shareholder. Over the last decade, billionaire wealth increased by around 7 percent annually. Since 2020, it has accelerated to 11.5 percent a year.

The term “shareholders” has a democratic ring to it, but this is patently false. In fact, it is the richest people in the world who own the largest proportion of shares, and indeed all financial assets. Research on twenty-four OECD countries found that the richest 10 percent of households own 85 percent of total capital-ownership assets — including shares in companies, mutual funds, and other businesses — while the bottom 40 percent own just 4 percent. In the United States, the richest 1 percent own 44.6 percent, while the poorest 50 percent own just 1 percent.

The rich are not only rich; they are predominantly men, and they are predominantly white. In the United States, 89 percent of shares are owned by white people, 1.1 percent by Black people, and 0.5 percent by Hispanic people. Similarly, globally, only one in three businesses are owned by women. So those bumper returns to shareholders are basically boosting incomes and wealth at the top.

How can we fix this? Taxing the superrich much more would be a great start; the news here is good, because Brazil, which is chairing the G20 group of the world’s most powerful economies this year, has put the need to increase taxes on the formal agenda for the first time. At the same time, President Joe Biden has once again said he supports a new billionaire tax.

But ultimately, tax is about fixing a problem after it becomes one. The key thing is ensuring the economy does not create such huge inequality in the first place. One critically important way to do this is to tip the scales back in favor of workers. The fruits of labor should be enjoyed by workers, not by those who, as John Stuart Mill said, “grow rich in their sleep without working, risking or economising.” This will only happen with an increase in worker organization and workers’ power. When workers’ power has been high, inequality has been low, and as the International Monetary Fund has pointed out, declining membership of unions has directly contributed to increases in incomes at the top.

Given this, the resurgence in strikes and increase in the power and voice of workers we have seen in recent years is amazing. It is still a fraction of what is needed to tip those scales, but a whole new generation of workers are seeing the power of organizing. Gen Z’s support for unions is the highest of any living generation. From the autoworkers in the United States to the garment workers in Bangladesh, we see workers fighting back against owners, and fighting for a fairer, more equal world.

Workers worldwide need to grab the scales and pull them back toward them; this will in turn create the politics and the economics of a new age of equality.

Republished from Tribune.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....

- By Gus Leonisky at 1 Jun 2024 - 10:20am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

squeezing your nuts....

The Labour Party Is Committing Itself to AusterityRachel Reeves is once again attempting to strengthen her credentials as a “sensible” manager of the UK’s finances. Labour’s shadow chancellor of the exchequer announced earlier this week that the party would introduce a new fiscal lock, under which any new changes to government spending require a forecast from the Office for Budget Responsibility.

The Labour Party has already tied its own hands when it comes to fiscal policy. The fiscal rule commits the party to balancing the books over the course of its first five-year term, and Reeves has also pledged not to raise taxes on big businesses or the wealthy.

Together, this means that Labour will not be able to increase public spending when it enters office. Barring a dramatic increase in economic growth — an extraordinarily unlikely scenario given the global economic context and Labour’s refusal to increase public investment — this means there will be no more money for public services without cuts to other areas of spending.

Even the arch fiscal hawks at the Institute for Fiscal Studies have questioned Reeves’s approach. The IFS has warned both parties that balancing the books by the end of the next parliament is likely to require an astonishing £20 billion worth of cuts per year. It called on both parties to “level with” voters about the trade-offs that would come alongside a commitment to balancing the books.

In other words, we are not getting the whole truth from the Labour Party. If they abide by their existing fiscal rules, the next government will have to commit to reimposing austerity.

Reeves’s recent announcement strengthens the argument that the Labour Party will seek to abide by their fiscal rules. If Reeves proposes a tax cut or a spending increase, then the Office for Budgetary Responsibility would have to report back on the likely impact of this move on the public finances.

But how will the OBR make these calculations? Historically, according to the New Economics Foundation, the OBR has “dramatically underestimated the impact of austerity on growth which ultimately led to higher national debt.” In other words, it has overemphasized the positive impact of cuts on the public finances in the short term without accounting for the long-term impacts of these cuts on economic growth.

Over the long term, austerity has undermined the foundations of our economy by increasing poverty, exacerbating disability and chronic ill-health, and constraining public sector investment.

When it comes to poverty, the failure of incomes to keep pace with wages is not just the result of the cost-of-living crisis — it’s also due to cuts to welfare payments and caps on public sector wages that were a central part of the cuts made since 2010.

Even before 2020, the UK had experienced the longest stagnation in wages since the Napoleonic Wars. Rising inflation exacerbated this challenge by eroding incomes further. We now have the highest rates of absolute poverty in thirty years, including a quarter of children living in absolute poverty.

Despite cuts to welfare payments, the increase in poverty means lower tax revenues and higher expenditure on income support. Greater levels of poverty also constrain demand, and, in an economy dominated by consumption, this equates to lower investment in the long run.

What’s more, higher rates of poverty have combined with greater levels of mental and physical ill-health to keep millions of people out of the workforce. Poverty is, in itself, in part to blame for worse physical and mental health outcomes — but so is the steady collapse in our health and social care services due in part to inadequate funding.

Fewer people in work means lower tax revenues and higher expenditure on income support — not to mention constraining growth over the long term by making it harder for businesses to attract and retain employees.

None of these factors make it into the OBR’s calculations. Why? Because the institution has chosen to adopt a particular approach to economic forecasting — one that overemphasizes the positive short-term impact of cuts on the public finances, and underemphasizes their long-term impact on growth. This is a political choice — even as it is presented as a neutral and technical one.

In fact, as Wendy Brown observes in her book Undoing the Demos, the depoliticization of policymaking has been a long-standing trend among neoliberal governments for the last forty years.

The mathematization of academic economics has involved attempts to impose the “right” answers to critical policy questions, such as the rate at which to levy corporate tax. The economist’s model might spit out a number — say 17 percent — which, they claim, will maximize revenues. But they won’t tell you the assumptions upon which that figure rests.

They might, for example, have assumed a certain percentage of revenues are lost to tax avoidance and evasion each year, which makes the “optimal” rate of tax lower than what you would expect with a more effective tax enforcement system. But this assumption is not something we must take for granted. We could use our limited resources to build a more effective tax enforcement system rather than cutting corporate taxes.

When these assumptions are not revealed, democracy suffers. The public is presented with a statement from an apparently objective economist that appears to have the status of fact: “The optimal rate of corporation tax is 17 percent.” There is no way to challenge this fact, because the political assumptions upon which the calculation was based are shrouded in secrecy.

Over the long run, the space for public engagement in policymaking shrinks. Political debates taking place between different social groups are replaced with technical debates taking place among policymakers.

Reeves’s decision to hand more power to the OBR exacerbates this problem. Rather than active democratic debate about taxation and spending, the public will instead receive pronouncements from on high as to whether a particular policy choice is “fiscally responsible.”

There will be no way for the average person to challenge these pronouncements, because these statements will be presented as facts, rather than the results of a particular organization’s calculations — calculations that are, as we have seen, inherently political.

In place of democracy, we end up with technocratic autocracy.

https://jacobin.com/2024/05/uk-labour-austerity-ifs-obr-reeves

NOTHING NEW HERE....

READ FROM TOP

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....

best bonuses....,

NOTHING NEW HERE....

READ FROM TOP

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....

poor to pay more....

The price of Biden’s new China tariffs By Patrick LawrenceThis is the opening move in a protectionist regime the U.S. president will extend significantly to prove his bona fides as a Sinophobe.

I love the photograph The New York Times ran atop Jim Tankersley’s May 18 story analysing the inadvisable raft of tariffs on Chinese imports President Biden authorised four days earlier.

There is the old coot signing the paperwork at a desk in the Rose Garden as a crowd of seven looks on admiringly. Polo shirts, sneakers, a baseball cap. Six of these seven are people of colour; four are women.

Perfect, just perfect. Study the picture. These dutiful onlookers are not officeholders or administration officials. They are union leaders from what were once powerful labor organisations: steelworkers, autoworkers, machinists, communications workers, the AFL–CIO.

These seven represent, in short, the very people who will get hit hardest as the executive order Biden just sent to Katherine Tai, his special trade representative, takes effect.

That’s Joe, isn’t it? The Man from Scranton has made his career gathering about him for the photo ops those toward whom he is indifferent and, often enough, those he is about to screw without a second thought (or even a first in Joe’s case).

Remember that famous occasion five years ago next month, when Biden finished addressing the Poor People’s Campaign in Washington about his plans to end poverty and then went to wealthy investors at the Carlyle Hotel in Manhattan to say that, if elected, “Nothing would fundamentally change”?

If he has by and large kept his word these past three years, something did change, something big, when, 10 days ago, he ordered a very wide range of import taxes on Chinese-made imports.

Will the U.S. make itself a manufacturing economy once again, bringing lost industrial production back from the dead? This is the stated aim of the new tariff regime, but no, what is done is done, in my view. Will America, in consequence of higher costs that are now inevitable, be a more expensive place to live for those to whom costs matter most? Yes, this will change, over time probably by a lot.

Biden’s trade and national security people, and you can’t tell one from the other these days, were preparing the ground for that Rose Garden moment for many months. They left intact tariffs of 10 percent, covering Chinese imports worth $300 billion, that Donald Trump imposed in September 2019.

But blocking exports in the other direction has been the Biden regime’s preoccupation. Under cover of “national security,” these include advanced semiconductors and other high-technology products in the White House’s attempt — it will never succeed — to subvert the Chinese economy in sectors wherein American companies cannot compete.

Don’t look now, but Joe Biden has just adopted the Trump China policy he has previously and relentlessly repudiated — and gone one further.

The May 14 executive authorisation is indeed a major escalation of the Trump administration policy. Steel and Aluminium, critical minerals (including so-called rare earths), solar energy panels, semiconductors, syringes and other medical equipment, those immense ship-to-shore cranes you see at seaports: The list of Chinese-made goods on which Biden will impose import levies is long, and the numbers high.

Duties on semiconductors double, to 50 percent. So do levies on batteries and battery components, from 25 percent to 50 percent. Tariffs on electric vehicles, China having made itself a global leader in EVs, go from 25 percent to 102.5 percent. This last comes close to an outright ban on the sale of Chinese electric cars in the U.S.

Some perspective here: The total value of the imports now to be taxed is $18 billion. Last year U.S. merchandise imports from China were worth $427 billion (as against exports to China of $148 billion), according to Census Bureau figures.

But in my read, Biden’s executive order is the opening move in a protectionist regime that will be extended significantly — especially in the near future, as Biden competes with Donald Trump and the hawks on Capitol Hill to prove his bona fides as a Sinophobe.

In essence, Biden just changed the direction of America’s transpacific economic policy. Chinese retaliation is more or less certain, and then it will be bad to worse for who knows how long.

Jim Tankersley, in that Times analytic piece noted above, was right to call Biden’s just-announced tariffs a shift of historic magnitude.

“Mr. Biden’s decision on Tuesday to codify and escalate tariffs imposed by Mr. Trump,” he wrote, “made clear that the United States has closed out a decades-long era that embraced trade with China and prized the gains of lower-cost products over the loss of geographically concentrated manufacturing jobs.”

This passage needs a little decoding, and I will get to that in a second.

With all those union chiefs around him, Biden went long, very long, on how this sprawl of import taxes will be to the benefit of American workers. That is not what this radical turn in policy is about, and I wish those labor leaders understood this better than they appear to have done.

I wish they had thought better of standing behind a president whose mind is on things far distant from the welfare of their memberships. The Chinese will not pay these tariffs, as various economists point out. Those union leaders’ dues-paying constituents will.

What Biden just announced is primarily the strategy of a nation that has hollowed out its industrial base — willingly, of its own accord — as it tries to project geopolitical power against a nation that has done just the opposite.

Closely related to this is a now-declared effort to protect the backsides and profits of American corporations no longer capable of dominating the globalised economy they so eagerly insisted upon but a couple of decades ago.

There are two other ways to look at this bold turn toward nationalistic protectionism.

One, the policy cliques in Washington and the corporations they serve are nearly frantic as the consequences of decades’ worth of careless economic policy, driven by greed and misapprehension, return to haunt them.

Keeping a competitor out by erecting walls made of import tariffs, when viewed from this perspective, is the desperate choice of people who simply cannot measure up to a moment that requires more intellect, imagination and courage than they can summon.

Two, the working and middle classes in America were sacrificed to those decades of corporate greed, as anyone paying attention at the time could discern without difficulty. They will be sacrificed a second time now, as Washington blunders on, this time in an effort to bring back what it decided 40 years ago it was all right to give away.

Since the opening of China

The historic opening to China in the 1970s had engendered, by the 1990s, all sorts of unschooled expectations neither Kissinger nor Nixon would ever have entertained. They were realists. Those who managed China policy from, say, the Clinton years onward professed motivations worthy of Victorian missionaries.

They were at bottom Wilsonians. Investing in China, they argued ad nauseam, will turn the Chinese into liberal democrats in the Western mold. James Fallows, the longtime Atlantic writer, called this during his time in Asia the “just like us” line of reasoning.

It seems almost too naïve to believe anyone took this stuff seriously, and maybe it was all along simply political cover for the greedfest it was used to justify. By the mid–1990s, as the Clinton administration was concluding the North American Free Trade Agreement, American corporations were piling across the Pacific by the thousands to invest in manufacturing platforms from which they exported goods back to the U.S.

In 2001 China gained membership in the World Trade Organisation. Its trade surpluses then grew precipitously, especially but not only with the U.S., but this was O.K.: Everybody was winning.

Three other trends complete this brief pencil-sketch.

One, any thought that Western investment would transform the Chinese into a nation of Westernised liberals — so devoid of any grasp of the dynamics of different histories, cultures, traditions, political systems and identity altogether — was revealed as the daydream of American-centric know-nothings.

This dawning realisation did not arrive well among the Sinophobes, notably the descendants of the “Who Lost China?” crowd on Capitol Hill.

Two, China proved an even more energetic climber up the development ladder than Japan or any of the so-called Asian Tigers.

The speed with which it made itself competitive in ever more advanced industries left American corporations and the untraveled policy planners in Washington, fair to say, flabbergasted. It had to: It has flabbergasted everyone.

Finally, in the decade after China joined the WTO, it became obvious, and in time a touchy political question, that the migration of so much U.S. manufacturing — south to Mexico via NAFTA, across the Pacific to China — had destroyed a great deal of the nation’s industrial base and countless of its communities while devastating the working and middle classes.

In more time it became obvious to the policy cliques in Washington that they no longer had an industrial base sufficient to their plans to salami-slice the U.S.–China relationship ever closer to open conflict.

David Autor, an MIT economist called these recognitions, in a 2016 study, “the China shock.” Happy talk gave way to bitter realities in that first decade after China, with strong U.S. backing, joined the WTO.

Autor and his two co-authors calculate that the wholesale migration of manufacturing to China had, by the time they wrote, destroyed a million manufacturing jobs and two and a half times that many when they counted jobs dependent on manufacturing.

It is a mystery why what American corporations and those in government serving them have done in the service of sheer profit lust came as a shock to anyone.

I wonder if a certain judgment has not been made. Precise figures are hard to come by, but in days gone by something more than a third of Chinese-made exports to the U.S. were the output of U.S. and other Western companies with mainland operations. Do the new Biden tariffs arrive because the party is over for the multinationals as China transforms itself into an advanced economy?

It is very strange to read about these events in corporate media, or listen to the government officials these media quote as authorities.

The worst of these tellings veer toward a version of the old “yellow peril.” The Chinese stole all these jobs! The Chinese, those untrustworthy inscrutables, tricked us into buying all these low-priced products!

It is not very flattering to mark down Americans as so helpless as this. But those who shape opinion in the U.S. have an old habit of casting America as the done-to, and those they do not like as the unjust doers.

More prevalent are the omissions and elisions. Things happen with no stated cause. Passive voice, long ago perfected at The New York Times, is a common resort. We need not look further than the lead paragraphs in Jim Tankersley’s May 18 analysis piece:

“For the first two decades of the 21st century, many consumer products on America’s store shelves got less expensive. A wave of imports from China and other emerging economies helped push down the cost of video games, T-shirts, dining tables, home appliances and more.

Those imports drove some American factories out of business, and they cost more than a million workers their jobs.”

Masterful. Consumer products, all by themselves, simply got cheaper: They decided this on their own, you see. These wandering imports, not American business people and policy planners, drove factories out of business. A million people were put out of work. There was no human hand in any of this, no one to fault, unless you want to blame the Chinese.

You will not read about any American chief executives in this kind of piece, or the policy decisions of any American official on up to the White House. It all simply happened.

Beware when the Times slips into the passive voice, readers: Subtly, subliminally, very effectively, you are about to be misled.

It is a question of admission and responsibility. No one in a position of power or influence wants to admit the grave, disloyal decisions that have shaped the Sino–American relationship on the economic side and no one has ever taken responsibility for the consequences, the abuses meted out to working Americans.

And so none of these irresponsible people could learn from their costly mistakes. And so they are now left to desperate attempts to repair the ship they are responsible for steering into the rocks.

The Trans-Pacific relationship

Taking the long view, when I consider the economic side of the trans–Pacific relationship I sometimes go back to 1955. That autumn my parents bought a brand-new Pontiac station wagon — gray and white exterior, red and white seats — and how vividly I recall the drive home from the showroom.

The thing was built to go to the moon and back. When my father gave it away to a friend in need, it was 11 years later and the car was still going strong.

Somewhere along the line, I mean to say, American companies determined not to compete any longer by producing superior manufactures but by producing and selling cheap manufactures. It was about price, not quality.

I have never approved of this strategic shift. It demeans the consumer, it serves as cover for stagnating wages, and it has a lot to do with the wholesale migration of U.S. production facilities to low-wage countries where cheap matters and quality doesn’t.

Edward Luttwak, the many-sided thinker often identified with conservative causes, had an interesting point in this line some years back. There is a hardware store in your town, and it sells hammers for $14. They were made in a factory in, let’s say, Tennessee. A few miles away there is a Wal–Mart that has huge bins of hammers, made in China, that sell for $3. Which does it make sense to buy?

Luttwak answered this way. (The hammer is my example, not his.) The Wal–Mart hammer is “cheaply expensive,” he would say: You get a $3 hammer, but the hardware store doesn’t survive, and with enough of these sorts of decisions your downtown doesn’t either. In time things go to shabby.

The $14 hammer, on the other hand, is “expensively cheap:” You pay more, yes, but in return you also get a town with a working commercial district, a Main Street to stroll, and altogether a sturdier community. The good people of Tennessee are better off, too.

I’m for expensively cheap. And Americans have been hooked, effectively, on cheaply expensive since the rush to China gathered momentum in the 1990s.

A question the Biden White House just put before us comes immediately to mind. Is it possible to restore a manufacturing economy that has been destroyed to the extent America’s has? Is this possible even in the selected industries the new tariff regime will protect? Or is this another mess on the way, another costly folly?

I am neither an economist nor an industrial planner, but, seat-of-the-pants judgment, I doubt such a project is feasible under our present circumstances — or maybe any circumstances. And I am certainly skeptical that all these Biden officials purporting to wisdom do not have it in them to manage an undertaking of this magnitude.

Straight off the top, any serious response to the crisis the U.S. now faces must begin with a top-to-bottom rethink of relations with China so that enduring solutions to problems that have two sides can be achieved. There is of course no chance of this.

On the domestic side things seem equally inadequate. The Biden regime proposes a plant here to produce high-end chips, another there to make something else. A mile from such plants there is no contemplation of change of any kind.

I read now that a chip plant in the Southwest is not getting built because there are not enough skilled workers to build it. Think about that just briefly. Is this a promising start along the highway to success?

A manufacturing base, as any good economic history will tell you, arises out of a sort of unified, societal thrust involving culture, social organisation, shared identity, shared aspiration. It cannot be declared in the Rose Garden and put immediately in place: It is accreted over generations of development.

It requires an educational base that the U.S. has also done well ruining. It requires changed social relations across the board, starting with a drastic, secular rise in wages so that they are roughly in line with, say, northern Europe’s. How good it would be if Americans could afford the expensively cheap alternative — a wise choice they would be right to make.

I’m not waiting for any of this out of the planners in Washington. I don’t see that they are serious people. They are ideologues, and ideologues are serious only about their ideology. I’m waiting for something I would rather not wait for.

I’m waiting for prices in the U.S. to rise in the service of an endeavour that never comes good. It will not be the first time ordinary Americans pay the price for enormous failures in high places. It will be the second, if we count from the “China shock” that should not have shocked anyone 20 or so years ago.

This article is from ScheerPost.

Republished from Consortium News, May 27, 2024

https://johnmenadue.com/patrick-lawrence-the-price-of-bidens-new-china-tariffs/

ALSO PUBLISHED:

The Price of Biden’s New China TariffsPATRICK LAWRENCE • MAY 23, 2024READ FROM TOP

THIS WAS TRUMP'S PLAN, POOPOOED BY THE DEMOCRATS THEN, NOW ADOPTED BY BIDEN.... AMERICAN POLITICS ARE A JOKE.....

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....