Search

Recent comments

- 2019 clean up before the storm....

2 hours 52 min ago - to death....

3 hours 31 min ago - noise....

3 hours 38 min ago - loser....

6 hours 18 min ago - relatively....

6 hours 40 min ago - eternally....

6 hours 46 min ago - success....

17 hours 14 min ago - seriously....

19 hours 58 min ago - monsters.....

20 hours 5 min ago - people for the people....

20 hours 42 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

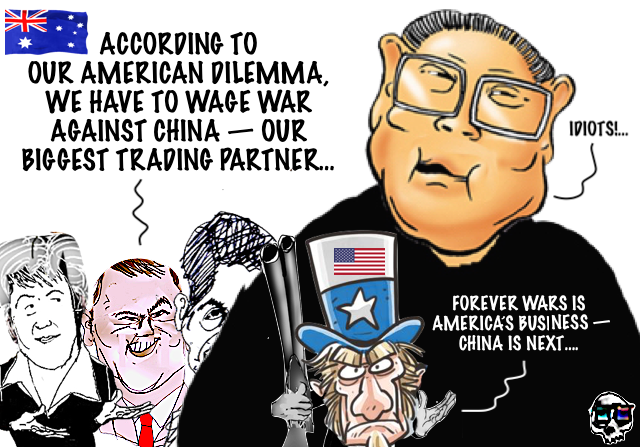

the business of american wars......

Allan Behm, head of international and security at the Australia Institute, discusses foreign affairs, defence, AUKUS and security issues facing Australia. Behm poses the question: do we know who we are and what we stand for in attempting to secure our national interest?

Defence: who are we, what do we stand for? By Allan Behm and Michael Lester

As we balance our relations with long time ally the United States and our economic relations with China in an increasingly fraught geo political environment, Australia is often fearful and lacking in confidence.

We confuse risks with fears, as Allan details in his book ‘No enemies, no friends‘, about our diplomacy and his forthcoming book ‘the odd couple’, about our alliance with America.

Listen to the full podcast here:

Allan Behm, Int’l & Security; Australia Instit (vol#371)

https://johnmenadue.com/defence-who-are-we-what-do-we-stand-for-ready/

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....

- By Gus Leonisky at 30 May 2024 - 10:32am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

frenemies....

If China is indeed a power to be worried about, wouldn’t Australia want to know as much about it as possible, perhaps even know what it is up to? Blocking or reducing interaction with China or other countries only reduces Australia to a petty, hollow state that is susceptible to misunderstandings.

Just a few years ago, Australia could not get enough of China.

Today, even Australia’s research efforts with China have plummeted to record lows.

The problem was so chronic that earlier this month, 60 academics penned a letter to Australia’s main funding research agency, the Australian Research Council, saying the production of core China research in Australia is in crisis.

They cite the Australian Academy of Humanities, whose report last year flagged little support for China-related research at scale.

The academy is concerned because having sovereign China knowledge capability is “critical to ensuring that challenges and opportunities are understood with Australia’s distinctive interests in view”.

There is little doubt the drop in Australian funding for research on China and research between Australian and Chinese academics has everything to do with the gnarly “red scare” that lingers in the western end of Asia-Pacific.

Just about everything including business collaboration with China has slowed in Australia for “national security” reasons.

Academics, whose goals are to amass and build valuable knowledge, know that a loss of an understanding of a key trading partner like China and a loss of an exposure to its innovation know-how are detrimental – for Australia.

Beijing’s record in the global academic scene is problematic, and fearmongers are quick to magnify it.

Some years ago, China’s Confucius institutes – although designed to teach Chinese language and culture similar to other promotional institutes like France’s Alliance Française or Germany’s Goethe-Institut – came under scrutiny for allegedly extending Beijing’s influence at overseas academic institutions.

None of these suspicions were proven, but analysts say there is good reason to assume these institutes would not be excluded from achieving Beijing’s goals and objectives.

Equally, media, anti-China proponents and even security establishments have sought to reinforce suspicions of Chinese academics on university campuses or to rubbish the reputations of academics who support collaboration with China.

Last week, Queensland University of Technology PhD student Xiaolong Zhu’s visa to study in Australia was denied on the grounds of being “directly or indirectly associated with the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction”.

I agree with Southern Cross University academic Brendan Walker-Munro who says in an analysis last week that while Zhu has not done anything wrong or been convicted of a crime, it reveals Australia’s rather patchy and blunt approach to “research security”.

But it is effective in carving political legitimations that China is an “enemy” in Australia, evidence or no evidence.

Australian and Chinese academics now tread a landmine-strewn landscape where, as the Australia-China Relations Institute says, any kind of collaboration could be seen as a conduit for espionage, foreign interference, intellectual property theft or supporting ends that are contrary to Australian values.

So, applications drop, grants shrink, research disappears. But who loses? Australia.

Australia loses because paranoia only achieves so much – mostly votes for politicians seeking to capitalise on fear and division.

If China is indeed a power to be worried about, wouldn’t Australia want to know as much about it as possible, perhaps even know what it is up to?

Former Australian diplomat Jocelyn Chey, one of the few Australians to study the Chinese language after the Second World War, says her studies helped her navigate pathways and avoid pitfalls for the benefit of Australia.

Just as the 60 academics wrote their letter, Chey also penned a local op-ed last week expressing concerns about the loss of China studies in Australia.

And it’s not just the Chinese studies that are declining in Australia, so are studies in other Asian languages such as Bahasa Indonesia, all of which are critical to Australia’s national interests.

Understanding others through language and culture shapes a more sophisticated Australia in its dealings with its closest neighbours.

Blocking or reducing interactions with China or other countries only reduces Australia to a petty, hollow state, susceptible to missteps, misperceptions and misunderstandings.

As the 60 academics write, “this trend runs counter to our national sovereign interests at a time when China is becoming increasingly more important to the Australian economy and also to our stability and security in Asia-Pacific”.

If the “enemy” description must stay, then Chinese literature, especially those by Chinese strategist Sun Tzu, is – ironically – pertinent to Australia at this point.

Shouldn’t Australia keep its friends close, but its enemies closer?

Republished from the South China Morning Post, May 24, 2024

https://johnmenadue.com/as-china-australia-ties-fray-should-canberra-keep-its-friends-close-its-enemies-closer/

READ FROM TOP

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....

RBO in the NDS....

Collision course: the National Defence Strategy and the China – Russia Joint Statement By Cameron LeckieAustralia is on a collision course with the major source of our prosperity. The collision is not yet a fait accompli. To avoid the collision will require breaking the shackles of the Rules-Based Order. Australia faces a geopolitical conundrum of major, if not epic, proportions.

With the recent release of the National Defence Strategy (NDS), the Albanese Government has confirmed that it is ‘all in’ with the rules-based order (RBO). The NDS claims that Australia’s future depends in large part upon upholding the RBO. To that end the fifth task of the Australian Defence Force is to ‘Contribute with our partners to the maintenance of the global rules-based order.’

In a momentous, if not epochal defining announcement, the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Foundation, released on 16 May 2024 a Joint Statement on the ‘Deepening the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership of Coordination for a New Era.’

This Joint Statement, building on a previous Joint Statement released immediately before Russia commenced its Special Military Operation in Ukraine, is a clear, direct and explicit repudiation of the RBO. The Chinese and Russian position is that the RBO is an attempt to subvert the recognised international order based upon international law by countries that adhere to ‘hegemonism and power politics.’

In the Joint Statement, Russia and China declare their opposition to the United States’ hegemonic behaviour including the assembling of military blocs. A clear reference to agreements such as AUKUS.

Australia finds itself in a situation where we have committed to maintaining the RBO (which Patrick Porter describes as being a ‘theology of restoration that frames foreign policy as a morality play’) whilst China has committed to opposing that order. Australia has thus put itself on a collision course with China, the major source of our prosperity. An irreconcilable position which is a direct consequence of ideology trumping strategy.

As the last phrase of the Joint Statement’s title indicates, the world has entered a ‘New Era.’ That new era sees the rise of the global ‘south’ or the global ‘majority’, and the decline of the West. This transition has been decades in the making, facilitated via a series of strategic blunders by the United States, supported by sub-imperial powers (such as Australia), and its vassal states. A tipping point was the proxy war in Ukraine which has greatly accelerated the transfer of the balance of power from west to east. We are now at the point where the United States’ imperial system is in free fall.

A symptomatic indicator of this decline is the regular, at this point almost routine, back firing of Western actions. Examples include the European Union’s 13 rounds of sanctions packages against Russia that have significantly weakened European economies whilst having limited impact on Russia, or the weaponisation of the US dollar which is rapidly contributing to the rise of alternate trading systems and de-dollarisation. These are examples, as described by Adjunct Professor Warwick Powell, of ‘autoimmune’ responses. Responses that weaken the West with limited impact on their target. AUKUS itself can be viewed as an autoimmune response to the unfolding collapse of Western hegemony.

How far will Australia go to ‘maintain’ the RBO? With the imperial system that underpins the RBO collapsing, irrevocably if the history of empires is any guide, then ‘maintain’ is an inappropriate verb. If as the NDS states Australia’s future depends upon upholding the RBO (which in itself is a dubious proposition) then the correct verb would be to ‘restore.’ Given the position elucidated in the Joint Statement, a restoration of the RBO would most likely lead to conflict between the United States and its coterie on one side and China and Russia on the other.

The existential question for Australia thus becomes, are we willing to risk war with our largest trading partner, or worse – World War Three, for the sake of restoring the RBO? A position that may be considered an auto-immune response on steroids!

What is striking about Australia’s position, as defined by the NDS, is how utterly unprepared we are for a major conflict. Just as the proxy war being fought in Ukraine against Russia has highlighted significant deficiencies in much of NATOs weaponry, doctrine, combat capability and industrial capacity, a conflict with China would very rapidly highlight how woefully underprepared Australia is from both the perspective of our combat capabilities and the Australian economy.

This highlights the sheer folly of the NDS. Not only has the NDS confirmed Australia is on a collision course with China (and Russia), but we are in no position to meaningfully fight, let alone win that conflict.

It is quite incredible that the leadership of any country could willingly place itself in such a position. We are not alone however in this folly. With the exception of outliers like Hungary, the majority of European governments have also adopted similar untenable strategies. The common denominator is the stranglehold with which the United States’ imperial infrastructure holds, like a cancerous growth, over Western institutions. Infecting not only the geopolitical culture but the key organs of state such as politics, defence, intelligence, and the media.

At this critical juncture, could Australia’s future be secured by an alternative to the increasingly problematic RBO?

Could Australia’s future be secured by an international order underpinned by international law, the United Nations and the United Nations Charter?

Could Australia’s future be secured by an international system where nations have the right to independently choose their economic and social systems based on their national circumstances?

Could Australia’s future be secured by an international system where foreign interference in our internal affairs and unilateral sanctions with no basis in international law is opposed?

Could Australia’s future be secured by an international system where disputes are resolved through negotiation and consultation by the countries directly concerned, without interference from external forces?

The answer to all these questions, and many similar questions, is a definitive yes.

These are some of the positions laid out in the Joint Statement. Read in its entirety the Joint Statement is a manifesto for a world that is more democratic, more equal and more secure. Not just for China and Russia, but for all nations. As such it offers a much more attractive proposition to the global majority than anything on offer from the collective West. It is also backed up by actions, not just rhetoric, as China’s Belt and Road Initiative demonstrates.

Australia has little to gain from upholding the RBO as the basis of our future security but much to lose. These losses may well result from ever increasing tensions with China, if not outright conflict. But these losses will almost certainly be realised through the many lost opportunities for Australia in the rapidly evolving multipolar world, in addition to the reputational losses accruing through our anachronistic clinging to the RBO.

Australia’s collision course with China is not yet a fait accompli. We can change course and be much the better for it.

It is time for Australia to break free from the shackles of the Rules Based Order.

https://johnmenadue.com/collision-course-the-national-defence-strategy-and-the-china-russia-joint-statement/

READ FROM TOP

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....

and more....

all dressed-up & no-where to go ....

our 'special' friend ...

mutually designed destruction...

all in the family .....

baerbock’s absurd comments violate china’s political dignity.......

jewish nazis.....there's more.....

the war can be provoked into being, and the victim blamed.....

china — a country with which we and the USA can and should coexist....\

wrongheaded in principle, but destined to fail in practice....idiots....

the world is a nail for the yankee hammer .....

the age pf privilege .....

out & about with Strangelove .....

so much to be proud of .....

the real mickey .....

ye gods !...

the tax game ....

turdy blossoms on the international stage...

lest we forget ....

takin' care of business ....

the empire had a tpp...And many more....

READ FROM TOP

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....