Search

Recent comments

- loser....

1 hour 43 min ago - relatively....

2 hours 5 min ago - eternally....

2 hours 11 min ago - success....

12 hours 39 min ago - seriously....

15 hours 23 min ago - monsters.....

15 hours 30 min ago - people for the people....

16 hours 7 min ago - abusing kids.....

17 hours 40 min ago - brainwashed tim....

22 hours 19 sec ago - embezzlers.....

22 hours 6 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

pondering about the racism of the german, american and israeli people.....

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has lashed out at Russian President Vladimir Putin for quoting iconic German philosopher Immanuel Kant. Speaking on Tuesday at an event marking the 300th anniversary of Kant’s birth, Scholz accused Putin of trying to “poach” the great thinker as well as misrepresenting his ideas.

Kant was born in 1724 in Koenigsberg (present-day Kaliningrad), which belonged to the Kingdom of Prussia before later becoming part of the Russian Empire. The philosopher is famous for his work on ethics, aesthetics and philosophical ontology, and is considered one of the pillars of German classical philosophy.

“Putin doesn’t have the slightest right to quote Kant, yet Putin’s regime remains committed to poaching Kant and his work at almost any cost,” Scholz said at the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences, as quoted by Die Zeit.

Scholz said Russia’s role in the Ukraine conflict contradicts Kant’s fundamental teachings. He referred to Kant’s words on the interference of states in the affairs of other nations, and defended Kiev’s decision not to engage in peace talks with Moscow. He said Kant believed that forced treaties were not the way to reach ‘perpetual peace’ – a reference to one of Kant’s major works.

Putin has been known to praise and quote Kant, even suggesting in 2013 that the philosopher should be made an official symbol of Kaliningrad Region.

During a meeting with university students in Kaliningrad in January, Putin called Kant “one of the greatest thinkers of both his time and ours,” and said the philosopher’s call “to live by one’s own wits” is as relevant today as ever.

https://www.rt.com/news/596464-scholz-putin-kant-poaching/

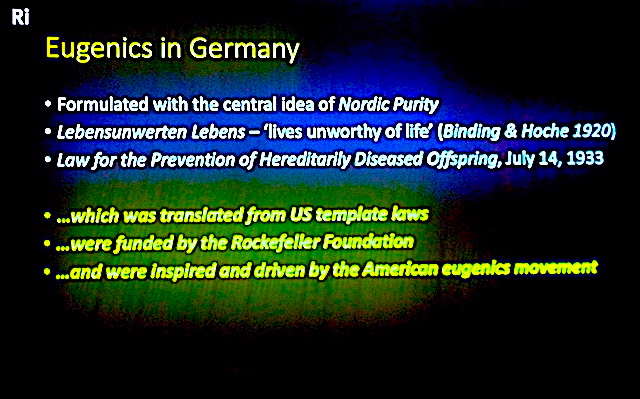

WHY AM I LINKING THE MORE RECENT HISTORY OF EUGENICS (SEE IMAGE ABOVE FROM YD POST) WITH IMMANUEL KANT? I HAVE NOT A FAINT IDEA... WE KNOW THAT RACISM AND ANTI-SEMITISM ISN'T NEW, AND HATRED OF THE "OTHER" COULD EVEN BE CLOCKED TO WHEN THE NEANDERTHALS WERE STILL A LIVING SPECIES.

THE PICTURE ABOVE ILLUSTRATES HOW BAD SCIENCE, "EUGENICS", WAS USED TO FILTER UNDESIRABLE IN THE AMERICAN SOCIETY. THIS AMERICAN SCIENCE WAS TAKEN BACK TO GERMANY TO JUSTIFY THE HOLOCAUST — EXTERMINATION OF JEWS, GYPSIES AND HOMOSEXUALS.

THE BAD SCIENCE OF EUGENICS CAME MOSTLY FROM ENGLAND AND HAD TRAVELLED TO THE USA IN THE 1920s — DISTORTED BY PEOPLE WITH BAD-WILL. EUGENICS WAS THEN EXTENDED TO BAD INTERPRETATIONS OF GENETICS....

WE ALSO KNOW THAT RACISM AND ANTI-SEMITISM WAS SOMEWHAT INGRAINED IN THE PROTESTANT RELIGION BY MARTIN LUTHER. HE HATED JEWS A LITTLE MORE THAN HE HATED THE MUSLIMS...

IMMANUEL KANT CAME ALONG AND POLISHED THE PHILOSOPHY OF EQUALITY AS LONG AS EVERYONE IS WHITE....

WITH THE "LITTLE HOLOCAUST" — A FULL-BLOWN GENOCIDE — HAPPENING IN GAZA, WITH THE EXTREMIST JEWS COMPARING THE GAZAN PEOPLE TO ANIMALS, WE NEED TO REVISIT SOME DIFFICULT IDEAS...

HERE WE GO...

Immanuel Kant was possibly both the most influential racist as well as the most influential moral philosopher in the history of modern, western thought. On the one hand, Kant's work and handwritten remains contain outrageously racist remarks. Moreover, Kant was arguably the first European thinker to produce an entire theory of race. 1 On the other hand, Kant's conception of all rational beings as “ends in themselves” is widely considered a paradigm of moral egalitarianism. Even more, his insistence on the inviolable dignity of each person and his ideas for “cosmopolitan” rights continue to be a major influence on contemporary moral and political philosophy. This stark contrast between Kant's racist remarks and his moral egalitarianism has inspired a long-overdue debate about the problem of Kant's racism: How could an ardent advocate of the universal dignity of all human beings simultaneously hold such despicable views about non-White people? And does the combination of these two facts indicate a failure of Kant's moral philosophy itself? Or does it merely indicate a failure of the person Immanuel Kant?

After a long period of almost complete complacency about Kant's racism in European and Anglo-American academia, recent scholarship has started to take Kant's racism seriously and profoundly deepened our understanding of both the historical development of Kant's views on race and the nature of his racism. Within the emerging literature on Kant's racism, scholars still virtually unanimously agree over framing the problem as choice between two interpretations of Kant's moral philosophy: either Kant was an inconsistent egalitarian, or he was a consistent inegalitarian. 2 Undoubtedly the majority of Kant scholars believe that Kant was an inconsistent egalitarian. On their view, Kant was simply inconsistent in that he failed to draw the necessary conclusions from his own moral philosophy. 3 By contrast, some scholars have argued that Kant was a consistent inegalitarian. On their view, Kant's racist remarks are not incompatible with his moral philosophy, because when Kant wrote about the dignity of all persons as ends in themselves, he did not mean to include non-White people. 4

Both sides of the debate agree that Kant's moral philosophy and his racist beliefs are not merely in tension but in obvious contradiction. 5 However, this assumption faces significant textual difficulties. Of the two most intuitive candidates for a possible contradiction, neither are as obvious as commentators have suggested. First, Kant's outrageous remarks about non-White people in his lesser-known writings never go as far as to literally deny their moral personhood. While his texts evince both bigoted prejudice and the belief that people of different “races” would have different psychological and physical characteristics that could be ranked, Kant's comments are never in outright contradiction with his view of each human being as an end in itself. Second, Kant explicitly denied that equal legal and political rights would follow from his conception of equal moral status: In the Doctrine of Right, Kant both explicitly affirmed the equal moral status of women while also denying them equal legal and political rights. If there really is any genuine contradiction between Kant's anthropological racism and his abstract egalitarianism, this contradiction is much less obvious than is usually assumed – if it exists at all.

Fortunately, these two interpretive options are not exhaustive, though the correct answer is much more worrisome for Kantian ethics than the two options presented so far. On my view, the verdict about Kant's racism and its relevance for his moral philosophy must be far more cynical than the two dominant interpretive options in the literature allow. Kant was arguably a consistent formal egalitarian: Kant's characterization of the equal dignity of all persons is so abstract that it remains largely useless as an antidote to racism. 6Consequently, we have to seriously question if Kant's language of universal human dignity really is the powerful tool against racism and misogyny that it is frequently said to be.

In the course of treating Kant's views as contradictory, most commentators still deny that Kant's racism demonstrates a philosophical problem – that is, a problem truly pertaining to the kind of moral philosophy Kant was committed to doing. Those who argue that Kant was an inconsistent egalitarian inadvertently portray the issue of his racism as a personal failure of Immanuel Kant but of no larger significance for his moral philosophy; on their view, the problem of Kant's racism is simply that Kant himself was capable of moral failure and cognitive dissonance, but his personal cognitive dissonance does not demonstrate any shortfall of his moral philosophy. Those who argue that Kant was a consistent inegalitarian inadvertently also risk portraying the issue of Kant's racism as primarily a personal failure. On their view, the problem of Kant's racism is that he did not include enough individuals in the community of persons, but once we admit that really all human beings are persons the story of Kantian abstract egalitarianism allegedly has a happy ending. By contrast, this paper joins a minority of commentators in arguing that Kant's racism really is a philosophical problem: It neither demonstrates the failure to overcome cognitive dissonance nor the failure to recognize some people as fully human; rather, Kant's racism demonstrates the failure of Kant's moral philosophy. However deep his insights were in other regards, his egalitarianism remained so abstract as to be almost entirely useless as an antidote to his own racism. In this way, the seeming compatibility between Kant's abstract egalitarianism and his racism also highlights a perennial philosophical difficulty: How do we get from abstract principles to substantive ideals in a way that doesn't merely polish up our existing prejudices?

In section two, I briefly highlight the standard assumption that unifies the great majority of contemporary interpretations of Kant's racism by recourse to two opposing (and equally invaluable) recent accounts. Section three argues that this common assumption faces textual difficulties by taking a closer look at the two most intuitively plausible candidates for a contradiction between Kant's account of moral equality and his racism. Finally, section four argues that this seeming compatibility between Kant's racism and his abstract egalitarianism is of wider philosophical significance.

2 The standard assumptionSo far, the standard approach to Kant's racism has been based in the assumption that Kant's racist remarks are in obvious contradiction with his moral egalitarianism, and that Kant's language of universal human dignity offers a powerful tool against racism and misogyny. Consequently, a central question of recent scholarship and popular commentary is how we should make sense of the apparent contradiction behind Kant's racism. 7 According to the more critical voices within the standard reading, the best way of making sense of Kant's racism is to see him as a consistent inegalitarian: When Kant spoke of the dignity of all human beings as ends in themselves, he did not actually mean it. But according to the majority of voices within the standard approach, the best way of making sense of Kant's racism is to see him as an inconsistent egalitarian: When he made his outrageous remarks about non-White people, he was not being a good Kantian.

Over the last decades, the consistent-inegalitarian reading has prominently been defended by Emmanuel Eze and Charles Mills. While Eze's interpretation of Kant's racism (on which Kant explicitly assigns different moral worth to different human beings) has not found many, if any, sympathetic readers, 8 Charles Mills has since powerfully argued that Kant was a consistent inegalitarian. Like Eze, Mills claims that the dignity of each person as an end in itself was only meant to apply to White people, and that Kant simply didn't consider non-White people to be persons. But unlike Eze, Mills claims that Kant had a silent taxonomy of moral worth, and thus implicitly distinguished not merely between persons (i.e., those with the capacity for practical reason) and things, but also between those human beings who are persons and those humans who are considered less than persons, or “sub-persons.”The “sub-person” category is, admittedly, a reconstruction of the normative logic of racial and gender subordination in his [Kant's] thought, a reconstruction that is certainly not openly proclaimed in the articulation of his conceptual apparatus, and may seem, prima facie, to be excluded by it. […] Nonetheless, I would claim that it is the best way of making sense of the actual (as against officially represented) logic of his writings, taken as a whole, and accommodates the sexist and racist declarations in a way less strained than the orthodox reading. 9

Mills provides two further claims to support this interpretation of Kant's thought. First, Mills points out that words can assume different meanings depending on their context, and invites us to consider that Kant simply did not really mean to include non-White people in his category of persons. Thus, although the Formula of Humanity (“So act that you use humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, always at the same time as an end, never merely as a means.” GMS 4:429) might sound egalitarian to us, Kant himself might not have meant it to include non-White people. Second, Mills has argued that ascribing such a hierarchy of persons and sub-persons to Kant's moral theory is, in fact, the only reasonably charitable interpretation of Kant's writings. In response to two authors who had previously defended the inconsistent egalitarian reading, Mills contends:How could it be more plausible to attribute to Kant the degree of cognitive dissonance requisite for the genuinely universalist reading of his work to be correct? I will put the contrast in the following stark form, to bring home (what I see as) the absurdity involved. […]

Unqualified Universalism: All biological humans/all races, as full persons, must be treated as ends, never as mere means.

Racist Particularism: The races of Blacks and Native Americans may be colonized and enslaved.

I submit to the reader that a contradiction so flagrant would have been noticed by anyone of the most minimal intelligence, let alone one of the smartest minds in the more than two thousand-year history of the western philosophical tradition. […] So, faced with the alternatives of a Kant blind to this flagrant contradiction and a Kant for whom there was no contradiction given the extent of radical interracial differentiation within the human race, the far more plausible interpretation seems to me that humanity was normatively divided for him. 10

This, it seems to me, is the strongest argument for ascribing to Kant the view of a consistent inegalitarian. As Mills knows, the actual text of Kant's moral philosophy cannot be squared with the idea that some human beings are not persons, that is, that some human beings do not have a dignity as ends in themselves. By tying the moral status of persons to their capacity for practical reason, and by further characterizing human beings as practically rational animals, Kant is explicitly committed to the view that all human beings have an absolute moral value that is entirely incommensurate. 11 The strength of Eze's and Mills' claim that Kant was a consistent inegalitarian ultimately comes from the apparent cognitive dissonance that Mills so poignantly describes in the passage above.

Although most Kant scholars have not followed Mills radical conclusion, they share Mills' view about the “flagrant contradiction.” But instead of concluding that Kant must have been a secret inegalitarian, they conclude that Kant must have been an inconsistent egalitarian. Lucy Allais, for instance, has recently argued that we should see Kant's racism as a lesson about the nature of racism in general – namely, that racism can involve a lot of cognitive dissonance and even the rationalizing of entirely irrational antipathies. As she puts it:Kant's practical philosophy cannot be made compatible with Mills' Untermensch postulation. However, I accept Mills' point about the dramatic and important inconsistency this requires ascribing to Kant, and how striking it is to think Kant could have not noticed such an obvious problem. I argue that rather than trying to make Kant consistent, we can use the example of Kant's racism to tell us something about the nature of racism. 12

Thus, Allais agrees not only that there is a “dramatic inconsistency” but also that it is striking that Kant did apparently not notice this “obvious problem.” This fact, she believes, can “tell us something about the nature of racism: How pervasive it can be in a person's belief system and resistant to evidence – as shown by the possibility of a person's not noticing obvious contradictions in their thinking.” 13 On this view, it now seems that Kant's racism might be an interesting empirical phenomenon, and moral psychology might have a place in explaining it. But on this view, it also seems like Kant's racism is not a problem for his moral egalitarianism. While Allais's emphasis that racism can involve deep-seated cognitive dissonance provides an important lesson, it also misses what is most worrying about the famous moral philosopher's racism: namely, that whatever the alleged contradiction between his abstract egalitarianism and his racism may be, it is simply not as “obvious,” “dramatic” and “flagrant” as either Mills, Allais or other contemporary Kant scholars present it. And this, as I will suggest below, has significant consequences for how we should understand Kant's ethics, and ultimately also for how we engage in moral and political philosophy more generally.

3 The problems for the standard approachAlthough Kant scholars have devoted significant efforts to making sense of the alleged contradiction between Kant's racism and his abstract egalitarianism, they have so far devoted little effort to examining the precise nature of the contradiction. One reason for this lack of interest might be that the basic outlines of Kant's moral philosophy, and in particular Kant's insistence on the inviolable dignity of each person, have become almost synonymous with moral egalitarianism in general. Thus, to question the idea that racist ideology necessarily contradicts Kant's abstract egalitarianism is a counterintuitive route, to put it mildly. 14 But if we really want to figure out if Kant's racism entails a failure of Kantian moral philosophy itself, rather than a mere failure of Kant the person, we had better pursue this route. As this section demonstrates, what seems intuitively contradictory to many contemporary readers did not seem so to Kant; and as I will emphasize in the following section, this lack of an obvious contradiction can tell us something significant about the potential shortfalls of Kant's account of moral equality and how we should do moral philosophy more generally.

Here, then, are some of the worst remarks we find in Kant's work about non-White people:- Humanity has its highest degree of perfection in the White race. The yellow Indians have a somewhat lesser talent. The Negroes are much lower, and lowest of all is part of the American races (PG 9:316). 15

- Whites contain all the impulses [Triebfedern] of nature in affects and passions, all talents, all dispositions to culture and civilization and can obey as well as govern. They are the only ones who always advance toward perfection (Refl 15:878, translation mine).

- [T]he Hindus have incentives, but they have a strong degree of composure, and they all look like philosophers. Despite this, they are nevertheless very much inclined toward anger and love. As a result, they acquire culture in the highest degree, but only in the arts and not in the sciences. They never raise it up to abstract concepts (V-Anth/Mensch 25:1187).

- The Negroes of Africa have by nature no feeling that rises above the ridiculous. Mr. Hume challenges anyone to adduce a single example where a Negro has demonstrated talents, and asserts that among the hundreds of thousands of Blacks who have been transported elsewhere from their countries, although very many of them have been set free, nevertheless not a single one has ever been found who has accomplished something great in art or science or shown any other praiseworthy quality […] So essential is the difference between these two human races, and it seems to be just as great with regard to the capacities of mind as it is with respect to color (GSE 2:253). 16

- Americans and Blacks cannot govern themselves. They thus serve only for slaves (Refl 15:878, translation mine).

- To adduce only one example: One makes use of the red slaves (Americans) in Surinam only for labors in the house because they are too weak for field labor, for which one uses Negroes (GSE 2:438n).

Quotes A-D clearly demonstrate that Kant believed in a racial hierarchy. Evidently, he believed that only (male) White Europeans have all the psychological and physiological “talents” that make human beings excel in work, in the sciences, and the arts. Quote E clearly indicates that Kant believed that some non-White people cannot politically govern themselves. And most importantly, quotes E and F might also suggest that Kant condoned slavery. In this context, is also worth noting that before writing the Metaphysics of Morals, Kant never explicitly condemned slavery. Although Kant was clearly aware of the heated debates between defenders of and critics of the institution of chattel slavery, 19 as well as the tortious treatments slaves were subject to, 20 he did not take an explicit stance on this topic in any of his published texts until the Doctrine of Right.

If Kant had condoned slavery for non-White people while also rejecting it implicitly through the Formula of Humanity and explicitly in his Metaphysics of Morals, this would indeed be a plausible contradiction. Although it is notoriously difficult to extrapolate what Kant might have meant exactly by treating someone as an end in themselves, and almost equally difficult to know what it means to treat someone merely as a means, 21 it is uncontroversial that treating someone as a living tool is incompatible with treating them as an end in themselves. However, Kant also denies that slavery (whether for non-White people or White Europeans) could be a rightful institution in his Metaphysics of Morals. 22 Already in the introduction to the Doctrine of Right, Kant claims that this volume deals with the relations between human beings who have both rights and duties vis-à-vis each other. By contrast, the book does not deal with humans' relationship to a being that has only rights but no duties (God), for a duty to such a being would be “transcendental,” that is, no corresponding external subject to whom this duty is owed could be found. And, most importantly, Kant also says that his book does not deal with relations to beings who do not have rights but merely duties (“serfs, slaves”). But Kant does not merely reject slavery as a potential topic of the book, leaving open that it could still be an otherwise acceptable institution. Kant explicitly rejects this potential topic as empty, because it would imply that there are human beings without personality. And because all human beings are persons a doctrine of right need not concern itself with such empty topics. 23 Moreover, in section I of the Doctrine of Right (which deals with the acquisition of a right to property in external objects), Kant explicitly denies that anyone could own other human beings. So someone can be his own master (sui iuris) but cannot be the owner of himself (sui dominus) (cannot dispose of himself as he pleases) – still less can he dispose of others as he pleases – since he is accountable to the humanity in his own person. (MS 6:270). 24

Despite rejecting slavery in general, Kant also makes an exception in the case of a criminal who has “forfeited his personality by a crime.” (MS 6:283). As Kant puts it, “Certainly no human being in a state can be without any dignity, since he at least has the dignity of a citizen. The exception is someone who has lost it by his own crime, because of which, though he is kept alive, he is made a mere tool of another's choice (either of the state or of another citizen).” (MS 6:329–30). 25 Notwithstanding this exception, Kant makes clear that such a loss of personality can only occur through a particularly grave crime. Thus, in the Doctrine of Right, Kant regards the legal institutions of slavery or serfdom as incompatible with the personhood of the subjugated. And however racist Kant's views of non-White people were, he clearly did not believe that not being White was literally a crime that would forfeit one's personality. As mentioned above, even the most critical interpreters like Charles Mills point out that Kant's work is incompatible with the denial of personhood to any human being merely because of the color of their skin.

Therefore, we might conclude that Kant's remarks on slavery in his unpublished notes for his lectures on anthropology (written sometime during the 1770s–1780s) are incompatible with his account of moral equality in the Groundwork as well as his substantive political and legal philosophy developed in the Doctrine of Right in the late 1790s. But consider again the following two remarks from Kant's preparatory notes on anthropology and his Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime:- (E) Americans and Blacks cannot govern themselves. They thus serve only for slaves.

- (F) To adduce only one example: One makes use of the red slaves (Americans) in Surinam only for labors in the house because they are too weak for field labor, for which one uses Negroes.

These two statements demonstrate Kant's uncanny indifference to the suffering of non-White people as well as his beliefs in both racially determined characteristics (both physical and psychological) and a racial hierarchy. The even more troubling fact, however, is that neither of these racist diatribes is, strictly speaking, incompatible with Kant's formalistic account of moral equality. Kant's view of moral equality in the Groundwork is based on the thought that all mature rational beings have the capacity for autonomous practical reason and are thus capable of setting themselves moral ends. And Kant believed that this claim can be derived from an analysis of our practical reason: In representing some of my ends as moral ends, I represent them according to a particular form (i.e., the categorical imperative); and this form can be expressed in different ways in order to highlight the commitments that result from this form of representing ends. One of these commitments is that insofar as I take myself to be capable of representing moral ends through my practical reason, I must also accept the capacity of every other rational being to set themselves ends through practical reason (i.e., as an end in itself). This special capacity for setting ends makes a living being into a person; and for Kant, this is what a person's dignity consists in. 26 Quotes A-D clearly display Kant's belief in a racial hierarchy based on the idea that only (male) White Europeans have all the psychological and physiological “talents.” 27 However, this belief by itself does not entail that Kant also believed non-White people are not in possession of practical reason and thus ends in themselves. Moreover, quote E does not claim that slavery or serfdom are rightful institutions (pace Mills' suggestion in the passage quoted above); rather, E claims that an entire group of people (most non-White people) would not be good at anything except serving as slaves. 28 The same applies to quote F. Notwithstanding its hideousness, it does not logically contradict either the view that all human beings are ends in themselves qua their capacity for practical reason, nor does it contradict Kant's claim that slavery cannot be a rightful legal institution. 29

But would it not be more plausible to think Kant changed his mind between writing the racist remarks E and F quoted above and writing his Doctrine of Right with its strict rejection of slavery? That Kant had “second thoughts” on race? Although I am quite skeptical of this conjecture, Kant may well have changed his mind. 30 Whether (and to what extent) he might have done so we will never know for sure. But whether or not he did so is, I believe, orthogonal to the present question – however interesting it might otherwise be. For the present question is whether there really is an obvious contradiction between Kant's racism and his abstract egalitarianism and what consequences this might have for our understanding of Kant's ethics and Kantian moral and political philosophy in general. If there is no such obvious contradiction, then this fact remains of philosophical significance whether or not (and to whatever extent) Kant might have changed his mind. 31

Alternatively, could it not be that when Kant denied that slavery could be a rightful institution in the Doctrine of Right, he held on to a silent taxonomy of persons, according to which some human beings are not persons (as Mills has suggested)? As I already pointed out above, the reason for ascribing such a silent taxonomy – contrary to what Kant explicitly says about all human beings being ends in themselves – has been the assumption that there is a “flagrant” contradiction between Kant's racist remarks and his abstract egalitarianism. However, Kant's racist remarks do not explicitly condone slavery, despite their hideousness; nor do they deny the personhood of non-White people. Thus, Mills overstates the reason for attributing such a silent taxonomy to Kant. If Kant's statements are not obviously contradictory, then we also have no obvious reason to assume a silent taxonomy either; and surely, we cannot presuppose a silent taxonomy in Kant only to then justify our attribution of this silent taxonomy to Kant by pointing to an alleged contradiction that itself relies on presuming that very silent taxonomy.

Although Kant's racist remarks do not, technically speaking, imply an acceptance of slavery, they still demonstrate his belief in a racial hierarchy – only (male) “Whites” are said to have all the psychological and physiological “talents” that make human beings excel. Importantly, quote (E) suggests that non-White people could not successfully govern themselves politically. Even if this is not an endorsement of slavery, at the very least it suggests that Kant did not endorse the idea of equal political and legal rights; and for the sake of the argument, we may plausibly take it to suggest that Kant also would not have endorsed equal rights to political participation and representation. 32 Could this be the “flagrant contradiction” that the standard reading assumes? Unfortunately, it cannot. The inconvenient truth is that Kant's abstract account of the moral equality of all persons in the Groundwork and the Critique of Practical Reason is just not obviously incompatible with inegalitarian substantive political doctrines. In fact, Kant himself explicitly considered the question what rights followed merely from the status as a person, and denied that this status would be sufficient for equal legal and political rights. For instance, in the Doctrine of Right, Kant makes clear that he believes women should not be accorded the same legal and political rights as men, while also explicitly affirming women's moral equality as ends in themselves.For instance, in a discussion of citizenship, Kant says:

[B]eing fit to vote presupposes the independence of someone who, as one of the people, wants to be not just a part of the commonwealth but also a member of it, that is, a part of the commonwealth acting from his own choice in community with others. This quality of being independent, however, requires a distinction between active and passive citizens, though the concept of a passive citizen seems to contradict the concept of a citizen as such. - The following examples can serve to remove this difficulty: […] a minor (naturaliter vel civiliter); all women and, in general, anyone whose preservation in existence (his being fed and protected) depends not on his management of his own business but on arrangements made by another (except the state). (MS 6:314)

In the paragraph immediately following Kant's characterization of women as necessarily “passive citizens” who should not be allowed to vote, he continues:This dependence upon the will of others and this inequality is, however, in no way opposed to their freedom and equality as human beings, who together make up a people […] But not all persons qualify with equal right to vote within this constitution, that is, to be citizens and not mere associates in the state. For from their being able to demand that all others treat them in accordance with the laws of natural freedom and equality as passive parts of the state it does not follow that they also have the right to manage the state itself as active members of it […] (MS 6:315, emphasis added)

Given his misogynistic discussion of the status of women, 33 Kant clearly did not believe that abstract moral equality, that is, the mere status of every person as an end in themselves, entailed that every person should also have even remotely similar legal and political rights – as we saw, Kant explicitly denied this. Instead, Kant's discussion of women and the family in the Doctrine of Right makes clear that he viewed some human beings as akin to children: Although they have dignity and are ends in themselves, he also believed that they would not have the physical and psychological abilities to successfully govern a body politic, a household, or even themselves. 34

READ MORE: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/papq.12444?af=R

MY ADVICE TO VLADIMIR PUTIN WOULD BE TO LET THE GERMANS HAVE KANT AS THEIR OWN AND HOLD ON TO KALININGRAD... IMMANUEL KANT EXPLAINS THE NAZIS.....

FREE ASSANGE NOW !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

- By Gus Leonisky at 26 Apr 2024 - 6:38pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

der philosophische glaube....

“In Defence of the Human Being”

by Moritz Nestor

An urgently needed book was published in 2020: In Defence of the Human Being. The author is Thomas Fuchs, philosopher, psychiatrist, and the Karl Jaspers Professor of Philosophy and Psychiatry at Ruprecht Karls University in Heidelberg. Fuchs’s book reminds us of the intellectual eradication we have witnessed in the human sciences since the 1960s and 1970s. Today, the human being seems to have disappeared from some areas of our human science disciplines.

Only recently, for example, a group of young social workers at a large psychiatric institution in Germany, who deal with the most serious problems on a daily basis, expressed their honest astonishment that the term “relationship” had never been mentioned in their training. Of course, the term was self-evident in their view. But in the scientific principles that they learned in their training for dealing with their patients, the word “relationship” was mentioned neither in theory nor in practice. They were essentially only familiar with ecological, cybernetic, and radically constructivist systemic approaches, mostly of US origin. The huge field of human scientific research on humans as cultural and relational beings, especially in Europe, was no longer taught. What happened?

Misanthropic aberrations: Deep ecology and transhumanism

There is, Thomas Fuchs begins his book, a long tradition “of putting humanity itself in the dock, of accusing it of excess, greed, hubris, or perfidy, of blaming it for the horrors of war or the destruction of the planet. Recently, there has even been an increase in statements to the effect that it would be best for the earth if it could free itself from its ‘coating of mould’, as Schopenhauer once called humanity”.1

Fuchs cites as examples the Voluntary Human Extinction Movement2 founded by Les Knight in 1991 and based on deep ecology, which pursues the “extinction of humanity to save the earth”, as well as the transhumanist3 Robert Ettinger, who wrote in his 1989 book, Man into Superman, that humanity is “itself a disease”. We must “set about curing ourselves of it”. Our species Homo sapiens is “only a bungling beginning”. When man “clearly recognises himself as an error”, he will be “motivated to form himself”4.

The human being: A living, bodily being in a relational space

Fuchs is concerned with the defence of the human being against challenges directed against the humanistic view of man and its core: the human person as a free, self-determining and social being connected to others. According to Fuchs, we humans are not “mere spirits” without corporeality, but “living beings” in “a shared relational space” and with a claim to respect our dignity, which humans “assert through their bodily existence and togetherness”.

From behaviourist conditioning …

Fuchs cites the book Beyond Freedom and Dignity by the US behavioural psychologist Burrhus Frederic Skinner, published in 1971, as a relatively early example of the questioning of the “humanistic personal concept of man”. It is a radical rejection of the personal conception of man.

“The belief in something like free will and moral autonomy”, Skinner wrote, “is the relic of a mythical, pre-scientific view of man. The attribution of personal responsibility and dignity hinders scientific progress”.

Skinner wanted to use social technologies to condition human behaviour in the same way that Pavlov conditioned his dog, whose saliva, after a while, would run only if the little bell sounded to announce the arrival of food. In this way, overpopulation and wars were to be discouraged and happiness instilled in humans.

… to the delusion of man as a will-less fulfilment organ of biochemistry and cybernetics

Recently, there has been less talk of Skinner’s frightening social utopia. But, according to Fuchs, Skinner’s basic idea is more relevant than ever: “to replace our self-image, which is biased by prejudice and myths, with rational knowledge of the human being and corresponding technologies”.5 For example, the Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari claims in his 2017 book, Homo Deus that artificial intelligence is gradually rendering the humanistic view of man superfluous. Fuchs describes Harari’s theory, also known as “posthumanism”, which is based on biology and cybernetics, this way:

People will no longer see themselves as autonomous beings running their lives according to their wishes, but instead will become accustomed to seeing themselves as a collection of biochemical mechanisms that is constantly monitored and guided by a network of electronic algorithms.6

Untenable assumptions

Harari says that in recent decades life sciences have relegated the free will, the “idea of an autonomous self” and the human “ego” to the realm of those imaginary stories about Christianity, St Nicholas, and the Easter Bunny.7 Homo sapiens is “an obsolete algorithm”.8 However, says Fuchs, Harari’s cynical deconstructivist theory has very real political consequences: Digital surveillance systems are being created worldwide using artificial intelligence. Fuchs believes that “something very like Skinner’s social technology is being realised”. Authors such as Harari uncritically adopt set pieces of a “scientistic view of humanity”. This includes three assumptions:

One, everything animate and inanimate can be fully explained scientifically. Two, subjectivity, mind, and consciousness are attributed to physical and physiological processes and are the products of nervous activity. Three, human subjectivity, spirit, and consciousness have no “independent effectiveness in the world”.

Today the biosciences see all organisms as biological machines, controlled by genetic programmes. Mental experience, inwardness – all this is merely an “effect of biochemical or evolutionary mechanisms”. What is alive is thus eliminated.

To this way of thinking, the human mind and consciousness are “neuronal information processing”, which in principle can run on any hardware and be simulated by computer systems.

In this way, the human being becomes the “sum of his data”, says Fuchs, and self-awareness, self-determination, understanding, self-reflection, and self-knowledge become superfluous – the algorithms know us better. Here again Fuchs:

The modern chorus of materialistic neurophilosophy proclaims that our subjective experience is nothing more than the colorful “user interface of a neuro-computer and thus a user illusion” (Slaby 2011) – only the neuronal computational processes in the background are real.

Self-knowledge, understanding, self-reflection, self-awareness and self-determination – in short, mental and spiritual life – are no longer a reality in this materialistic world view; they are a naïve, nostalgic belief.

To summarise, the following picture emerges: the modern “posthuman” materialist says that everything is matter that can be fully investigated by science. Consciousness, thinking, and feeling derive from physical-chemical nerve activity: “neuronal data processing”. Like a computer.

Human consciousness: events bound to physicality in the interpersonal space.

For Fuchs, consciousness, thinking, and feeling are not physical-chemical processes. Translated into everyday language, Fuchs says analogously:

Just as a melody, although it cannot be heard without a piano, is not contained in the material of the piano keys or can be explained by these keys, a person cannot express consciousness, thinking, and feeling without a brain and body. The melody is not the sequence of keys. It sounds in the spiritual space within and between us humans. So we always think and feel in the social space of social relationships. Thinking is therefore always interpersonal thinking, and feeling is always interpersonal feeling. A person without social relationships, which would of course be unthinkable, would not need to think, feel, or even speak.

We feel as whole beings – not with the brain alone

According to Fuchs, materialism cannot be effectively countered by opposing it argumentatively to an abstract, disembodied, pure spirit. Rather, according to Fuchs, it requires casting the human person as a body-soul unity. According to Fuchs, the humanistic view of the human being shows “that human beings are present in their own body, that they feel, perceive, express themselves and act with their body”. When we humans meet, it is not brains that meet. It is the same with every life process. In reality, every human person does not act as a brain, but as a self-determined organism that is an inseparable unity of body and soul.

According to Fuchs, interpersonal relationships are therefore not the contact of brains, but “intercorporeality”. This means: My hand is not a piece of flesh, but an animated part of a living organism. We do not understand other people “by means of a theory of the mind”, Fuchs remarks, but rather

“intuitively on the basis of their physical expression, their gestures and their behaviour. Just a few weeks after birth, babies recognise the emotional expressions of the mother or father, namely by understanding and feeling these expressions’ melody, rhythm, and dynamics in their own bodies.” (p. 13)

Hence, also, digital online communication always presupposes that we are dealing with “a living person made of flesh and blood”. The “feeling body” also feels sympathy in virtual spaces. We immediately understand what Fuchs means: In the cinema, it is not just the neurons in my brain that use a “theory of mind” to analyse what is going on outside the cave of my head on the screen. If the virtual mountaineer on the screen falls on the north face of the Eiger in a snowstorm, we react with our whole body.

Humanism of the embodied living spirit

This view of the human being as a body-soul unit – which neither materialistically sees everything spiritual as a higher nervous activity nor assumes an abstract disembodied spirit – is what Fuchs calls “embodied anthropology”, a “humanism of the living embodied spirit”. This is actually a view that Aristotle had already recognised: the experiencing and self-conscious organism.

Taking this view of the mind-body problem, Fuchs agrees with Adolf Portmann’s“basal anthropology” and with the concept of man we find in Adlerian individual psychology – which already emphasises the indivisible mind-body unity in its name – as well as with neo-psychoanalysis and with the psychosomatic research of Franz Alexander, Thure von Üexküll, and others, to name just a few important researchers.

In his defence of the human being, Fuchs starts with this fixed point, with the “what” question, “What is the human being?”, to take a stance against the ongoing anti-humanist stream of false theories which radically question nothing less than the freedom and continued existence of the human species. This is not simply a theoretical question, says Fuchs, but an ethical and, above all, an eminently political one.

The concept of man: An eminently political concern

“For as Karl Jaspers wrote, the concept of man that we hold to be true”, Fuchs writes, “ultimately determines our treatment of ourselves and others – today we would have to add: and nature”. He elaborates:

Humanism in its ethical sense therefore means resistance to the rule of technocratic systems and constraints as well as to the objectification and mechanisation of human beings. If we perceive ourselves as objects, be it as algorithms or as neuronally determined apparatuses, we surrender ourselves to the rule of those who seek to manipulate such apparatuses and dominate them socio-technologically. “For the power of Man to make himself what he pleases means […] the power of some men to make other men what they please”.9 The defence of man is therefore not only a theoretical task, but also an ethical duty”.10

This is completely in the spirit of Karl Jaspers as he wrote in “Der philosophische Glaube” (1974): It is “the concept of man which we hold to be true that ultimately decides how we treat ourselves and others” – today we would have to add: and nature.

https://www.zeit-fragen.ch/en/archives/2024/nr-8-16-april-2024/verteidigung-des-menschen

GUSNOTE: GUS DOES NOT BELIEVE IN THE SOUL AND IS A RABID ATHEIST

POLITICAL CARTOONING SINCE 1951

READ FROM TOP

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....