Search

Recent comments

- success....

2 hours 20 min ago - seriously....

5 hours 4 min ago - monsters.....

5 hours 11 min ago - people for the people....

5 hours 48 min ago - abusing kids.....

7 hours 21 min ago - brainwashed tim....

11 hours 41 min ago - embezzlers.....

11 hours 47 min ago - epstein connect....

11 hours 58 min ago - 腐敗....

12 hours 17 min ago - multicultural....

12 hours 24 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

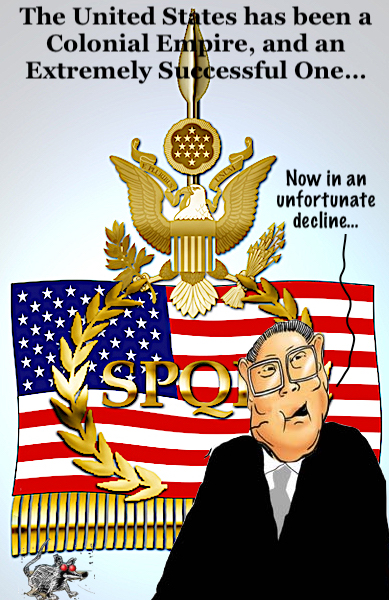

"I see no empire"....

For those who remember their high school textbooks, the issue of America's imperial history is very clear cut. American imperialism, the textbooks told us, was that fairly brief period in American history that lasted from 1898 to 1945. This was the period during which the United States acquired a number of overseas territories, including the Philippines and Puerto Rico, among others. The era of imperialism, we are told, ended in 1945 when the Philippines was finally granted full independence from Washington. Even more dubious—the textbook writers tell us—is the idea that the US is or has been a colonial empire. After all, American citizens did not set up any colonies in the Philippines or in Puerto Rico in the way that British migrants populated Virginia or New England.

For those familiar with military conquest in North America during the nineteenth century, however, it seems a bit odd that so many historians have agreed that the American empire did not begin until 1898. After all, if an empire is an expansionist state that annexes territories and rules over the inhabitants found there, the Mexicans and Apaches—to name just two conquered groups—will likely disagree with the textbooks.

Indeed, the colonial and imperial status of many polities over time and place has been hotly debated. For example, some scholars claim Ireland was never a colony of the United Kingdom.1 Nor can many scholars decide if Siberia was part of a colonial Russian empire.2 In the minds of many, Washington's imperial acquisitions are similarly ambiguous.

Yet, any frank assessment of American political history should lead us to conclude that yes, the United States was very much a colonial empire throughout most of its history. What is different about the United States, however, is that it has been a fabulously successful colonial power. It is so successful, in fact, that the territories that used to be obvious colonies have ceased to have a distinct identity incompatible with the metropole's preferred political and cultural institutions. Those former colonies have now been fully merged into the metropole itself. Thus, commonly used definitions of "colony" or "colonialism" no longer describe these conquered territories in the twenty-first century. The methods by which these areas were acquired, however, were clearly methods of colonial imperialism. Ironically, the very success of American colonization efforts has hidden the empire in the mists of the past.

What Is a Colonial Empire?It seems we have to supply our own definition of colonial empire since scholars can't agree on one.3 To help us, we can draw on the work of Michael W. Doyle in his book Empires.4 According to Doyle, one primary aspect of imperial relations is clear: there is an asymmetrical relationship between the colony and the metropole. The metropole is much more powerful in terms of its military and economic resources. A second key aspect is that political entities within the colonies are clearly distinct from the metropole. Doyle also states that these territories are not free to leave the metropole's control; they are maintained by coercion within a political union. Moreover, these subject territories are defined by a local lack of cohesion, especially compared to the metropole itself. Finally, the imperial territories contain a population—often a minority group—that has a stake in expanding the metropole's power.

Clearly, the US's frontier territories during the nineteenth century nearly all fulfill these requirements in the period following annexation and preceding admission as states. For example, in territorial areas that later became Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, and surrounding areas, decades passed between the time these lands were annexed by the US, and the time when they became full states.

During this period, these territories existed in a clear asymmetric relationship with the US government in which the residents did not possess the same legal rights as residents of states. Territorial residents did not have voting representation in Congress or the electoral college. Territorial legislatures were not constitutional bodies and did not possess the legal prerogatives of state governments. These territories were, in all topics that really mattered, ruled directly from Washington. Moreover, political control within the territories was heavily fractured. Indian tribes and the white populations all vied for power and territorial control. In the southwest, these groups were joined by former Mexican citizens who competed with both the Anglo population and the tribal populations for power within the new borderland territories. All were dominated by the metropole's power, and none enjoyed the full legal rights of state residents.

Importantly, these territories were maintained by coercive means. No areas claimed by the Washington metropole, whether states or not, were permitted to leave the Union. Obviously, had residents of New Mexico territory—which remained a non-state territory for 64 years—voted to rejoin Mexico or declare independence, this would not have been recognized by the regime in Washington. The American Civil War made it abundantly clear that the metropole was likely to respond to any declaration of independence with military intervention.

Finally, all these territories contained populations with a stake in maintaining imperial control. In the years immediately following annexation, these were usually the small minority of white Anglo settlers, speculators, and nationalists who promoted more white settlement and a stronger union with the metropole.

Looking at all this we can conclude that yes, the period between annexation and statehood clearly fits the description of what we would call imperial rule.

We must then answer the question of whether or not this imperial rule was colonial in nature. On this, there is even less doubt. After all, it was the success of colonization efforts that enabled the metropole to consolidate rule in the new territories with relative ease.

We can see the colonization process at work in the years following annexation. Sometimes, the process even informally precedes annexation, as in the territories seized from Mexico and Spain. But, to use Colorado as an example, we find the usual colonial process at work: what is now Colorado was added to the Union in pieces. First, eastern and northern Colorado was added via the Louisiana purchase. The southern and western portions of the state were added in the wake of the war with Mexico. Initially, these areas were politically unorganized and functioned simply as an imperial possession containing highly localized political institutions. These small polities were controlled by Mexicans, Indian tribes and white Anglos. It was through the process of colonization by white settlers that Colorado eventually became "suitable" for membership as a state.

Unofficially, the Anglo populations of the metropole believed the same thing about former Mexicans. It was only after non-Hispanic white migrants overwhelmed the former Mexican territories that these areas were considered reasonable candidates for representation in the national legislature. Indeed, a major factor in New Mexico's long wait for statehood stemmed from the fact that the Mexican and Indian population there was "too large." That is, it took an unusually long time for non-Hispanic whites to obtain a sufficiently large majority in the territory. The non-Hispanic whites delayed statehood until they were sure that Anglos would dominate the state legislature. In most areas, the process of replacement via migration and colonization was much faster. The sheer volume of white settlers moving into places like Iowa, Kansas, and Oregon quickly rendered the local tribal populations politically irrelevant. Only then was the statehood process allowed to proceed.

The Myth of Benign American "Westward Expansion"This all conflicts with the common grade-school myth about how "westward expansion" worked. According to the myth, the United States was admittedly expansionist, but everywhere it went, it granted the conquered residents citizenship, and equal rights with all other Americans.

The reality was something quite different. Indians in the conquered territories were considered to be non-citizens indefinitely, and certainly incapable of civilized self-government. The local indigenous populations, of course, were not granted the same legal rights as the whites. This didn't even happen with tribes that adopted "white" ways such as agriculture, written language, and constitutional legal structures. These so-called "five civilized tribes" were ultimately given the treatment we would expect for any indigenous population in any French or British colony in the glory days of traditional colonial imperialism. Most tribal members were not granted citizenship until 1924, and even then, some state governments denied them the vote.

Unofficially, the Anglo populations of the metropole believed the same thing about former Mexicans. It was only after non-Hispanic white migrants overwhelmed the former Mexican territories that these areas were considered reasonable candidates for representation in the national legislature. Indeed, a major factor in New Mexico's long wait for statehood stemmed from the fact that the Mexican and Indian population there was "too large." That is, it took an unusually long time for non-Hispanic whites to obtain a sufficiently large majority in the territory. The non-Hispanic whites delayed statehood until they were sure that Anglos would dominate the state legislature. This use of this strategy also betrays the contention that the conquered Mexicans were offered full citizenship. These Mexican-Americans were often promised certain legal rights on paper, but since they were denied control of their own legislations and legal institutions, legal machinations in California and Texas ensured the former Mexicans did not enjoy these rights.

Yes, legal rights were granted to most of the conquered populations eventually, but often the process took decades. In the meantime, the American metropole employed strategies including population replacement and military "pacification" as a means of consolidating its rule. The process employed from annexation to statehood was a typical process of imperial colonialism.

So where is the colonial empire today? It practice it has ceased to exist—precisely because it was so successful. Thanks to the success of the colonization process, tribal populations and Mexican-American populations were rendered largely invisible for a century after annexation.

The Russian ExampleThe Russians met with similar success in a similar way on their own eastern frontier. As with the United States, the process began first with annexation through either diplomacy or military conquest. To consolidate this rule, however, the Russians needed colonists. Fortunately for the Russian metropole, the colonists were available, and in the "late imperial period, in particular the period between the late 1880s and 1916, was a time of massive peasant migration when millions of peasant settlers were resettling from European Russia to borderlands in the Russian 'East.'"5 Although the Russian process bears many similarities to the American one, the Russian regime unwisely called itself an empire. Thus, the process of Russian colonization in Siberia is more readily described as such.

British and French FailuresToday, the areas regarded unambiguously as the subjects of colonial imperialism as those areas where the process was never all that successful. The British, of course, attempted to colonize Ireland—"this first colony of the British empire"—in the old-fashioned way. Scottish settler colonies were encouraged in Ireland in earnest beginning in the late seventeenth century.6 These settlers never overwhelmed the local population in the way that the whites did in North America, and the Irish free state successfully seceded in 1922. We might also look to French Algeria which was intended to be an extension of metropolitan France in every way, complete with full representation for the residents in the national legislature. The French, however, lacked a ready reservoir of Gallicized settlers, so it could not overwhelm the Algerian natives and consign them to political minority status. This precluded the extension of French legal rights to the overall Algerian population. This broad extension of legal status had only been made possible in the United States by the fact that American settlers—settlers readily acquiescent to the metropole's rule—created a new majority that displaced the uncooperative natives. Since nothing similar could be achieved in Algeria, political rights had to be tightly controlled to a select minority. This led inexorably to rebellion and secession in 1954. Similar failures were endured by the metropoles in Kenya, Rhodesia, West Africa, India and Indochina. In all these cases, the process of colonization and population replacement was never sufficient to consolidate the metropole's rule for the long term. Yet, because these former colonies have maintained a distinct identity to the present day, we recognize the metropole's attempts to conquer them as colonialism and imperialism.

In contrast, the residents of the American colonies—now mere extensions of the metropole—were reduced to minorities lacking a distinct political identity. The only vestiges of this can be found today in the system of Indian reservations which, of course, continue to be directly governed by federal law. Thus, we no longer call them colonies, and it becomes much easier to shrug and say "what empire? I see no empire."

https://mises.org/wire/united-states-colonial-empire-and-extremely-successful-one

- By Gus Leonisky at 27 Jan 2024 - 5:32pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

you = zilch.....

by Eric Zuesse

No, they don’t. Here is the answer to this question that was supplied on 1 February 2005, in an article that was published by a journal of the American Political Science Association, American Political Science Review, titled “Who Influences U.S. Foreign Policy?”, excerpted here:

The implications of our findings for previous research connecting public opinion and policy making are sobering. …

The estimates of strong business influence hold up under different models, for different political and institutional conditions, and for different time periods. They hold for high- as well as low-salience issues, for a variety of substantive issue areas, and with respect to different institutional groups of policy makers (though especially for executive branch and Senate officials). … To our surprise, public opinion — the aggregate foreign policy preferences of ordinary citizens — was repeatedly estimated by our Models 1–3 to have little or no significant effect on government officials. … These results contradict expectations [not “findings” but “expectations”] drawn from a large body of previous research. … It [prior research] has seldom systematically examined the relative impact of competing influences. … [In other words: this was the first empirical study on this question. Even as-of today, no second such study has been published.]

The apparently weak influence of the public [on U.S. foreign polices] will presumably disappoint those adherents of democratic theory (e.g., Dahl 1989) who advocate substantial government responsiveness to the reasoned preferences of citizens (Page and Shapiro 1992). Our findings indicate that the gravitational pull on foreign policy decision makers by the “foreign policy establishment” (especially business leaders and experts[who are hired by those “business intersts” or actually America’s billionaires who control them]) tends to be stronger than the attraction [that’s their word meaning “affect” or “impact”] of public opinion. This is consistent with the pattern of extensive and persistent “gaps” that Chicago Council studies have found between the foreign policy preferences of the public and those of policy makers. For example, ordinary Americans, more than policy makers or other elites, have repeatedly expressed stronger support for protecting Americans’ jobs, stopping the inflow of illegal drugs, and reducing illegal immigration, as well as for a multilateral, cooperative foreign policy based on bolstering the United Nations, working closely with allies, and participating in international treaties and agreements (Bouton and Page 2002; Jacobs and Page 2003). …

Our finding of a substantial impact on foreign policy by business — generally a greater impact than by experts — suggests that purely technocratic calculations do not always predominate in the making of foreign policy. Competing political interests continue to fight over the national interest, and business often wins that competition.

This finding was subsequently bolstered by political-science empirical studies on the broader question of whether the U.S. Government is controlled by and serves its public (i.e., is a democracy) or instead only by its extremely richest (i.e., is an aristocracy), all of which studies have found that America is not a democracy but instead an aristocracy. It’s a dictatorship by its richest 0.1% of its richest 1%, or by its richest hundred-thousandth of the U.S. population, but especially by the 400 richest Americans, all of whom are multi-billionaires and control America’s international corporations, which profit enormously from these foreign policies.

Nor are America’s foreign colonies (or ‘allies’) democracies, either. Most of its colonies are in Europe; and on 28 February 2013, the British Journal of Political Science published an empirical study, “Determinants of Upper-Class Dominance in the Heavenly Chorus: Lessons from European Union Online Consultations”. Here is its summary or “Abstract”:

Social science literature contains ample warning that even if a range of methods exists for involving external interests in policy making, external interests still do not necessarily have equal opportunities to voice their concerns. Schattschneider’s oft-quoted indictment of the American interest-group system that ‘the flaw in the pluralist heaven is that the heavenly chorus sings with a strong upper-class accent’ has been echoed in subsequent studies not only of the United States but also of other political systems.1 However, even if the literature finds strong support for the conclusion that business interests dominate at the aggregate level, such a finding masks considerable internal variation. The bias in the heavenly chorus is not equally strong every time it sings, because a number of characteristics related to the performance itself may affect the degree of bias. It is, therefore, surprising to find a lack of studies explaining and empirically testing the conditions under which we are likely to see different levels of bias in the participation of substantive interests between cases. Moreover, studies often draw conclusions on bias without explicitly relating the distribution of active interests to that of the interest-group population as a whole.

In this research note, we analyse a new dataset of participation in the European Commission’s online consultations during the last ten years and compare it to the population of registered interests. Our aggregate findings show that business dominance in consultations is even higher than in the population of registered groups. Moreover, our findings offer a first systematic empirical, large n test of how the character of different types of policy affects participation patterns. We find a linkage between characteristics of policies and degrees of bias in individual consultations. Participation on expenditure issues with direct consequences for budgets is more diverse than on regulatory issues, where private actors primarily cover the costs. Finally, a narrower range of interests mobilize on proposals with concentrated costs than on proposals whose costs are carried by a broader range of stakeholders. We start the note by briefly reviewing the literature on bias in interest representation and considerations of the conditions under which we should expect it to vary. Thereafter, we examine how the character of policy affects mobilization patterns.

This should not be surprising, because the EU was set up by the U.S. Government after WW II, as part of its war to conquer Russia — the political-economic part, not the military part, NATO — recognizing the fact that in order for the coming U.S. empire to be able to repeat Hitler’s Operation Barbarossa, it would have to be initially an invasion from Europe, and so gaining political and military control over European nations would be crucial in order for the U.S. regime to become enabled to do successfully what Hitler’s German regime had tried but failed to do. America’s billionaires are determined to control Russia, and the vast majority of Europe’s billionaires have joined them in this imperialistic effort.

Like all empires, the U.S. empire is a network of aristocracies. The public exist only as soldiers to carry out the conquests using the weapons that the billionaires’ ‘defense’ firms sell to the Government, and as taxpayers to fund those soldiers and weapons. And, of course, as voters, to select from amongst the political candidates that those billionaires have decided to fund and to promote.

So, it all makes sense, that the opinions of the American people don’t affect U.S. foreign policies, regardless of how much those foreign policies affect the American people — such as by their injuries, deaths, and soaring U.S. Government debt in order to fund the purchases of all those weapons and the employment of the soldiers to use them.

This is the reality of America’s ‘democracy’.

—————

Investigative historian Eric Zuesse’s latest book, AMERICA’S EMPIRE OF EVIL: Hitler’s Posthumous Victory, and Why the Social Sciences Need to Change, is about how America took over the world after World War II in order to enslave it to U.S.-and-allied billionaires. Their cartels extract the world’s wealth by control of not only their ‘news’ media but the social ‘sciences’ — duping the public.

https://theduran.com/do-the-opinions-of-the-american-people-affect-u-s-foreign-policies/

SEE ALSO: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z_jJbgMZN34

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....