Search

Recent comments

- brainwashed tim....

1 hour 44 min ago - embezzlers.....

1 hour 50 min ago - epstein connect....

2 hours 2 min ago - 腐敗....

2 hours 21 min ago - multicultural....

2 hours 27 min ago - figurehead....

5 hours 35 min ago - jewish blood....

6 hours 34 min ago - tickled royals....

6 hours 42 min ago - cow bells....

20 hours 34 min ago - exiled....

1 day 1 hour ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung... internationalism vs globalism....

By 1923, in most of Europe at least, the gunfire had ceased. Yet in Germany, a group of young academics felt that the social upheaval following World War I still had the potential to produce catastrophe — and believed that an institute for social research was a necessary step to meet this challenge.

BY MARC ORTMANN

Already in the early part of the decade, Felix Weil, Max Horkheimer, and Friedrich Pollock had conceived the idea of establishing such a body in Frankfurt. These friends envisioned an institution that would undertake both theoretical and empirical research on society, with the aim of finding a more humane and just model for the future — while also reflecting on why the November Revolution and other recent attempts at revolution in Germany had failed. The idea was supported by Weil’s father, who was a benefactor of the University of Frankfurt.

Carl Grünberg, the institute’s first director, officially gave it a Marxist orientation. During his inaugural lecture, he passionately pledged his commitment to Marxism and declared his intention to use historical-materialistic research methods in his scientific tasks. Since the approval of various actors and administrations had to be obtained for the institute to be founded, Weil originally concealed the Marxist orientation by using “Aesopian language” in the founding document in 1922.

The unambiguous naming of the research program by Grünberg in 1923, which referred to Marx, therefore surprised and shocked many conservatives present who worked in and around the University of Frankfurt. Grünberg had in 1911 founded the journal Archiv für die Geschichte des Sozialismus und der Arbeiterbewegung (Archive for the History of Socialism and the Labor Movement), which became the most important publication of the institute’s early years.

The institute began its public activities at Whitsun 1923 with the “Erste Marxistische Arbeitswoche” (“First Marxist Work Week”), in which many young socialist intellectuals from across the continent participated, such as György Lukács, Karl Korsch, and Karl August Wittfogel. During this period, the institute also took part in other forms of international exchange resulting from Grünberg’s collaboration with David Ryazanov, a well-known editor. Ryazanov and the Austro-Marxists around Grünberg had agreed in 1911 on publishing a complete edition of the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. With the decision of the Fifth Congress of the Communist International, Ryazanov, the director of the Marx-Engels Institute in Moscow, came to Frankfurt in 1924 to begin work on the complete edition in cooperation with the institute.

In Germany, a group of young academics felt that the social upheaval following World War I still had the potential to produce catastrophe.

For years, the staff worked on sifting, archiving, and documenting the writings of Marx and Engels, culminating in the first part of the complete edition in 1927. However, this cooperation was anything but free of conflict — the institute, always striving for an objective edition and a scholarly tone, increasingly resisted the political instrumentalization of this project, which led to the joint dissolution of the cooperation in 1928. Moscow had too often taken a commanding tone. Editors in Frankfurt resisted encroaching Stalinization, as Weil wrote in 1928: “You cannot ask me to persuade people who ask me for information to go to Moscow under these conditions, by which I do not mean the material conditions, but the others…”

Grünberg’s tenure as the institute’s first director also came to an end that same year, as after suffering a stroke, he was no longer able to fulfill his duties. Max Horkheimer took over as the next director and shifted the emphasis from orthodox Marxism to an interdisciplinary approach: under his leadership, socio-philosophical, sociological, economical, literary, and psychoanalytical disciplines were combined, and staff from these different disciplines were employed. With the Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung (Journal for Social Research), a publication was founded that led academic debates throughout the 1930s, with prominent authors such as Leo Löwenthal, Friedrich Pollock, Theodor W. Adorno, Erich Fromm, and Walter Benjamin.

A Journal for Social ResearchMax Horkheimer’s stated aim for the Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung was to bring together a wide variety of studies and approaches to the elaboration of the social. Hence, he gave the journal the purpose of exploring contemporary “society as a whole,” as he mentioned in the first preface. It should not distance itself from empirical work or lose itself in pure theoretical debates but link them. This meant that the journal should be a compilation of the different ways of looking at the world, always finding concrete reference points for them within contemporary debates.

Different experts from their disciplines contributed to this, such as Fromm from psychoanalysis or Löwenthal from literature. The aim was to formulate a critique of the prevailing conditions through interdisciplinary empirical work that would also stand out from the positivist scientific establishment.

The journal also stands as an example of the institute’s history. While the first issue in 1932 was still published in Germany and dealt with National Socialism as a possible coming regime, the next issues were published in Paris and the last two in New York City. With the development of National Socialism and the location of the institute in Switzerland and later in the United States, the viewpoints on social developments also changed. However, the journal was never just a study of political contexts, but also combined aesthetic reflections, such as the one by Adorno on Richard Wagner.

Critical Theory and ExileIn the early years before the Nazis came to power, Horkheimer and his colleagues conducted research to understand why the socialist revolution did not happen as Marx had predicted. Through their studies on family, personality, and authority, they discovered that a significant portion of the working class did not identify with the idea of a socialist revolution, but rather with conservative political views. As a result, the institute and its environment became increasingly cautious, as they anticipated an authoritarian takeover in Germany.

In 1932, Horkheimer founded a branch office of the institute in Geneva, attached to the “Internationales Arbeitsamt” (“international labor office”) with the official purpose of conducting research, but also as a preparatory measure for a possible exile. Under his direction, the Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung was moved to Paris, and the foundation’s funds were transferred to the Netherlands. Horkheimer himself started living in different hotels to avoid being captured.

However, their plans were met with the harsh realities of social upheaval. The first Frankfurt phase ended 1933 with the confiscation of the institute and its archive by the Gestapo (secret state police), leading to their closure. Horkheimer led the institute through the years of exile, first from Geneva, then from the United States, and tried to continue their work while taking staff members with him into exile. This sad chapter of history is particularly evident in critical theory thinkers who became victims of the Nazi regime, such as Benjamin.

Theories, Traditional and CriticalOther members of the institute, including Horkheimer, Adorno, and Herbert Marcuse, continued their work in exile in the United States. During this time, they developed critical theory, which was a Marxist-inspired approach to studying society and culture that aimed to reveal and challenge the underlying power structures that shape social life.

Telling of this approach was “Traditional and Critical Theory,” a seminal essay by Max Horkheimer that compares and contrasts what he calls the two forms of social theory. Horkheimer argues that traditional theory, which focuses on social order and stability, is limited in its ability to understand and change society. It locates social problems on the side of individuals and thereby reproduces social contradictions.

In contrast, critical theory, which focuses on power and domination in society, seeks to challenge the status quo and promote social change. Horkheimer emphasizes the importance of the critical stance, which consists of always starting over and recognizing the relationship between intellectual positions and their social location. He believed that the future of humanity depended on the existence of critical theory and its ability to promote social justice and equality.

During their years in exile, the institute not only kept a watchful eye on Europe, engulfed in the flames of war, but also scrutinized the developments in the US.

Despite all the challenges faced, the years in exile were also marked by enormous productivity. Groundbreaking work was produced in the Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung — always in the conviction that it was necessary to intervene, even without being able to participate. “But,” Horkheimer insisted “the idea of the Institute was not to submit so easily to this reality. Maybe it will happen, but at least it won’t be without resistance.”

During their years in exile, the institute not only kept a watchful eye on Europe, engulfed in the flames of war, but also scrutinized the developments in the United States. The institute analyzed speeches by fascist agitators, explored the emergence of radio and light theater as mass media, and observed the rise of Hollywood. Divided into two regional groups, with one in New York and the other in Los Angeles, Horkheimer and Adorno, alongside other exiles like Thomas Mann and Bertolt Brecht, had the opportunity to closely study the emergence of Hollywood’s shining stars in Los Angeles. It was during this period that they produced one their most significant works, the Dialektik der Aufklärung(Dialectic of Enlightenment), which was completed in the United States and published in 1949 after the end of their exile.

Like other works by the Frankfurt School scholars, it posed the question of how, after the developments of modernity in the Enlightenment, it was possible to reach the sheer horror of the concentration camps of National Socialism. Was this not impossible, the end of all reason, or had reason actually played a role in it? Written by Horkheimer and Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment explores the relationship between the Enlightenment and modernity and the emergence of totalitarianism in Western societies. The main point of the book is the Enlightenment project, which aimed to liberate humanity from ignorance and superstition, had paradoxically led to the emergence of new forms of domination and oppression in modern societies.

After the WarAfter the end of the war, the institute had to make a far-reaching decision: should it stay in the United States or return to Frankfurt? In the letters between the protagonists, long-standing disputes can be traced, which nevertheless led to the decision to return and to the construction of the present-day institute. After the destruction of the previous building during the war, the old institute moved into the current premises and developed an unprecedented closeness to the students in the 1950s. In this new phase, which was about the formulated goal of strengthening individuals, Horkheimer and Adorno showed themselves with a joy in teaching and a hidden radicalism — a radicalism in the seminars behind closed doors.

As the internal protocols of those days show, there was also talk at the institute with students and staff about a formulation of theory that would remain faithful to “Marx, Engels and Lenin” (as Adorno put it) and be directed against the then chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, the Christian Democrat Konrad Adenauer.

Among the staff and students are quite a few who were to decisively shape the German research landscape in the following decades, such as Jürgen Habermas and his continuation of critical theory, Elisabeth Lenk and her research in literary studies, Regina Becker-Schmidt and the extension of critical theory to feminist issues, or Friedrich Weltz and his pioneering work in qualitative social research.

For Horkheimer and Adorno, the Enlightenment project, which aimed to liberate humanity from ignorance and superstition, had paradoxically led to the emergence of new forms of domination.

Even though their paths led away from the institute, they continued the history of the institute as a teaching institution. This list should of course also include the connections to Habermas, as was the case with Axel Honneth, a later director of the institute, or the Marxist connections in the form of Alfred Schmidt, Hans-Georg Backhaus, or Jürgen Ritsert.

However, this closeness became more fragile in the 1960s. During the student revolt of this period, demands were made that the directors did not want to meet in the desired sense. Hans-Jürgen Krahl, a student of Adorno’s who died young, formulated this rupture as a swan song from the revolution to his former teacher, who had decided to call the police on the student protesters. Many voices assume that without Krahl’s tragic death, the history of the West German left would have been different.

In any case, this break in the close relationship between teacher and student can be taken as exemplary of the break between critical theory and the student movement. Further breaks also occurred with Habermas’s departure from Frankfurt and the separation of the joint path of the institute and critical theory. While critical theory and references to its basic positions were now continued elsewhere, the institute critically dealt with its legacy.

An example of this is the seventy-fifth anniversary celebration in 1999 and the criticism associated with it. The history of the institute, it seemed to the critics, was reduced to Horkheimer and Adorno; meanwhile the dismantling of staff members’ rights of democratic codetermination, which had existed in the 1970s, went ignored. In 1999, it appeared that the Institute for Social Research and critical theory had finally separated; Honneth, a later director of the institute, even asserted that for him the tradition of critical theory at the institute no longer existed.

Back to the FutureAs the institute’s new director, Stephan Lessenich wants to accentuate references to the oldiInstitute and critical theory more sharply. For him, the anniversary is a unique opportunity to reform the institute and, in its present constitution, to link it to the old critical theory. The anniversary will give the work at the institute a broad public and develop a new research program in the coming years. This will also deal critically with the history of the institute and should leave behind the “self-chosen provinciality.”

While voices — from Breitbart News to Steve Bannon — in the alt-right and far-right media are spinning conspiracies about theIinstitute’s great influence having a firm grip on American society and politics and that critical theory is a true brainchild of Satanism, the current situation in Frankfurt is quite different. Lessenich wants to contribute to a globalization of critical theory in the basic position of not easily submitting to this reality. Lessenich says:

In terms of referring back to the tradition of critical theory, we aim at developing a critical sociology of domination that keeps pace with the times, with the current mode of domination. And we try to contribute to a thinking in alternatives, in alternative forms of organizing society, by way of the negation of the current state of affairs — just as critical theory always did.

This approach, which Lessenich talks about and mentions as the present goal of the institute, can be exemplified by the work of one of its current members, Alexandra Schauer.

Her monograph Mensch ohne Welt (Man Without World) can be understood as a fresh reference to the early basic attitudes of the institute. As a member of the institute’s staff, she investigates the (perceived) loss of creative possibilities in late modernity. Using the axes of time, the public sphere and the city, she meticulously traces socialization into and out of modernity.

These and similar works in today’s institute represent the history of resistance of the institute and formulate the “back to the future — putting contradictions back into the center of critical social analysis and empirical social research,” that Lessenich is striving for. Or to put it in Schauer’s words ahead of the institute’s centenary: “Let’s try what seems impossible, let’s save what is possible!”

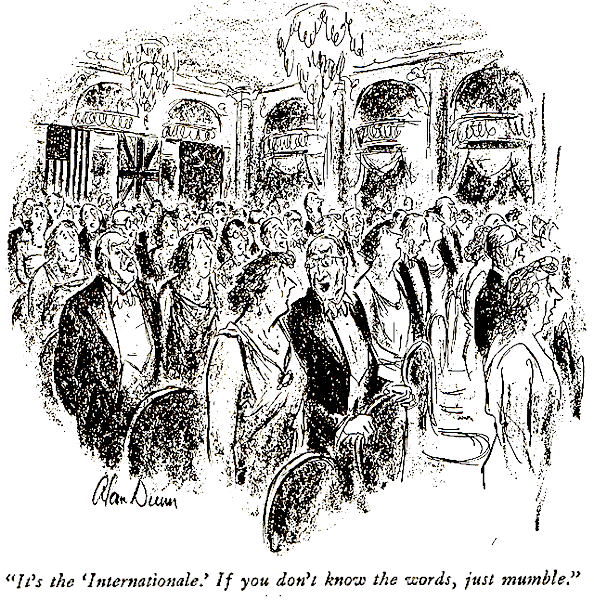

Cartoon at top from The New Yorker, c.1950.....

- By Gus Leonisky at 19 Oct 2023 - 4:14am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

arise.....

The International

Arise ye workers from your slumbers

Arise ye prisoners of want

For reason in revolt now thunders

And at last ends the age of cant.

Away with all your superstitions

Servile masses arise, arise

We’ll change henceforth the old tradition

And spurn the dust to win the prize.

Refrain:

So comrades, come rally

And the last fight let us face

The Internationale unites the human race.

No more deluded by reaction

On tyrants only we’ll make war

The soldiers too will take strike action

They’ll break ranks and fight no more

And if those cannibals keep trying

To sacrifice us to their pride

They soon shall hear the bullets flying

We’ll shoot the generals on our own side.

No saviour from on high delivers

No faith have we in prince or peer

Our own right hand the chains must shiver

Chains of hatred, greed and fear

E’er the thieves will out with their booty

And give to all a happier lot.

Each at the forge must do their duty

And we’ll strike while the iron is hot.

READ FROM TOP.

Debout! les damnés de la terre

Debout! les forçats de la faim

La raison tonne en son cratère,

C’est l’éruption de la fin.

Du passé faisons table rase

Foule esclave, debout! debout!

Le monde va changer de base

Nous ne sommes rien, soyons tout!

Refrain

C’est la lutte finale

Groupons-nous et demain

L’Internationale

Sera le genre humain.

Il n’est pas de sauveurs suprêmes:

Ni dieu, ni césar, ni tribun,

Producteurs, sauvons-nous nous-mêmes!

Décrétons le salut commun!

Pour que le voleur rende gorge,

Pour tirer l’esprit du cachot

Soufflons nous-mêmes notre forge,

Battons le fer quand il est chaud!

L’etat opprime et la loi triche,

L’impôt saigne le malheureux,

Nul devoir ne s’impose au riche,

Le droit du pauvre est un mot creux.

C’est assez languir en tutelle,

L’égalité veut d’autres lois;

«Pas de droits sans devoirs», dit-elle,

«Egaux, pas de devoirs sans droits!»

Hideux dans leur apothéose,

Les rois de la mine et du rail

Ont-ils jamais fait autre chose

Que dévaliser le travail?

Dans les coffres-forts de la bande

Ce qu’il a créé s’est fondu.

En décrétant qu’on le lui rende

Le peuple ne veut que son dû.

Les rois nous saoulaient de fumées.

Paix entre nous, guerre aux tyrans!

Appliquons la grève aux armées,

Crosse en l’air et rompons les rangs!

S’ils s’obstinent, ces cannibales,

A faire de nous des héros,

Ils sauront bientôt que nos balles

Sont pour nos propres généraux.

Ouvriers, paysans, nous sommes

Le grand parti des travailleurs;

La terre n’appartient qu’aux hommes,

L’oisif ira loger ailleurs.

Combien de nos chairs se repaissent!

Mais si les corbeaux, les vautours,

Un de ces matins disparaissent,

Le soleil brillera toujours!

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....

I am the poor....

By Jim Mamer / Original to ScheerPost

“The capitalists tell us it is patriotic to fight for your country and shed your blood for the flag. Very well! Let them set the example.”

– Eugene Debs

National Rip-Saw Editorial

August 1914

In the first part of my examination of missing information on labor history in high school history textbooks, the focus was on the years preceding World War I beginning with the exploitation and inevitable revolts of enslaved Africans and African-Americans to the abusive conditions of workers which lead to thousands of strikes.

This second part begins around WWI. By that time, opposition to the conditions of the working class in American industrial capitalism had taken different forms. The struggle led some to call for reform within capitalism while others, identifying as socialists, anarchists, or communists, preferred more extensive change.

Defining Terms or NotI found no real attempt, in the textbooks, to examine what these different ideologies stood for. That makes it difficult, if not impossible, for students to understand why laborers and their leaders identified as they did. I have to believe that neglecting to define these various positions is deliberate because it avoids any controversy.

Even simple explanations, such as those below, would help students understand labor history. I encourage readers who are also teachers, to use these definitions with their students and to invite them to look up the material for themselves in order to develop definitions they are comfortable with.

In textbooks, socialism is most often defined as an economic system “based on government control.”

In the United States, socialism came to encompass a wide range of economic policies that demanded government take action to improve the economic and social conditions of the working class. Socialism also became an umbrella term for those who felt that labor had been cheated out of its share of newly created wealth. The socialist leader and five-time presidential candidate Eugene Debs wrote that he had been influenced by thinkers like Edward Bellamy and Karl Kautsky. Others were influenced by the utopian socialist Robert Owen.

In the textbooks, anarchism is often defined as a rejection of all governments. And, contrary to popular opinion, anarchism never advocated chaos.

In the real-world anarchism has more than one definition and these sometimes overlap.

Individualist anarchists stress the isolation of the individual and emphasize the individual’s right to own their tools and the products of their labor. They were variously influenced by the American Josiah Warren, the Italian Luigi Galleani or the American Henry David Thoreau.

Social anarchists encourage collaboration through mutual aid and advocate non-hierarchical forms of organization. They were influenced by the French writer Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and the Russian born Emma Goldman.

Communism developed out of the socialist movement in 19th-century Europe. In reaction to the Industrial Revolution, communists blamed industrial capitalism for the misery of the working class. In general, communists were influenced by the ideas of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky or the Russian Revolution itself.

Among labor leaders who accepted capitalism, Samuel Gompers is probably the most well-known. For years he was the leader of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), which was composed of a collection of craft unions.

Gompers had no desire to unite the working class and instead advocated for “pure and simple” unionism of skilled workers focused primarily on economic rather than political reform. He insisted labor organizations work for reform within capitalism.

Defining capitalism is more complex. Outside the world of textbooks, its roots are attributed to Adam Smith who, in his 1776 book, “The Wealth of Nations,” describes early competitive economies upending what he labeled mercantilism: a system in which monopolies and trade guilds controlled much of the economy.

Smith never used the term capitalism; he wrote about what he called “commercial society.”

It is within this commercial society that he wrote, “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.” Smith opposed conglomerates, monopolies, guilds and unions because they can manipulate, along with their allies in government, both supply and price.

The textbooks suggest definitions of capitalism that are both limited and impossibly static over time. One text defines it as a system where, “producers and consumers are motivated by self-interest.” And another as “a system in which factories, equipment and other means of production are privately owned rather than controlled by government.”

Most textbooks never mention the name of Adam Smith and rarely use the word capitalism, preferring to talk about a “free market” or “free enterprise.” Students ironically? would learn more by reading Wikipedia.

If textbooks are to help students understand history, that is, if they are to educate, they must purposely define terms that are, in most cases, very poorly understood.

For any textbook to assume that high school students understand what capitalism, socialism, anarchism or communism are is negligent. And assuming that students understand how these ideas have evolved over time is absurd.

Labor During and After WWIRidiculous as it may sound, high school texts are expected to cover almost everything important or interesting in U.S. history. Every textbook I’ve seen chooses to attempt that in chronological order, forcing the narrative into jarring jumps from subject to subject.

Thus, too many textbooks begin to explore the subject of labor in early industrial capitalism and then drop it completely to discuss immigration or American imperialism (1898). Then, thirty or forty pages later, the discussion shifts to WWI, the Espionage and Sedition Acts or Women’s suffrage. Over and over, one thing is forced to follow another.

The fact that historical events are interrelated is not easy to explain when they are discussed in self-contained sections or when inconvenient information is simply left out.

All textbooks, of course, discuss the United States entering WWI, three years after the war began in Europe, in 1917. And most texts mention that, in the same year, the communist Bolsheviks won the Russian Revolution. This is unusual because American history textbooks focus almost exclusively on events in the United States.

Nevertheless, all the texts I’ve worked with mention the Bolshevik Revolution and they assign it a domestic purpose.

It is almost always discussed within the context of rising labor tensions within the United States. Thus, linking poorly defined and unexamined domestic political ideologies to the Russian Revolution. Here are two examples:

In November 1917, a group of revolutionaries, who called themselves Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir I. Lenin [sic], seize power and eventually establish a state based on the social and economic system of communism…. Two years after the revolution, in March 1919, the Third Communist International meeting was held in Moscow. Under the banner of their symbolic revolutionary red flag, communist speakers advocated worldwide revolution – the overthrow of the capitalist system and the abolition of free enterprise and private property.

In “The Americans,” immediately following the paragraph above, it is reported that “70,000 radicals joined the newly formed Communist Party in the United States.” In “History Alive!,” the long simmering revolution is introduced by reporting that, “American communists drew inspiration from the Russian revolution of 1917.”

Despite reports of victory, the revolutionary government in Russia was not stable. The new government faced economic pandemonium, food shortages, military disorder and increasing popular demands that the country withdraw from the battlefield.

By 1918, the Russian government began to pull out of the war. Although conveniently absent from every text I have seen, the Russian withdrawal from WWI seemingly inspired President Woodrow Wilson to order American armed forces to Siberia to join an attempt to remove the new communist government.

The Espionage and Sedition Acts used against Labor

Back in the U.S., in an increasingly anti-immigrant atmosphere, Congress passed a new Espionage Act of 1917 which was said to protect the American effort in WWI from “disloyal European immigrants.”

Although it is rarely mentioned in textbooks, the Bolshevik victory evolved into a justification for an increase in anti-labor policies in the U.S. It became common, oftentimes without reason, to accuse labor activists of being Bolsheviks or, if you will, Russian agents.

In 1918, Congress then passed the Sedition Act which expanded the crimes defined in the Espionage Act “to include any expression of disloyalty to, or contempt for the US government or military.”

Both the Espionage Act and the Sedition Act were originally directed at socialists, pacifists and anti-war activists most of whom were also labor rights activists. Some argued that these acts clearly violated the First Amendment, but the Wilson Administration argued that they were necessary to the war effort.

When these acts were used to prosecute more than two thousand anti-war activists, the Supreme Court upheld those convictions. In 1920, the Sedition Act was repealed by Congress, but the Espionage Act remains in effect to this day. Both whistleblower Edward Snowden and the publisher Julian Assange have been charged under its, seemingly flexible, provisions.

The Anti-Labor Red ScareTextbook coverage of the Russian Revolution is usually followed by section titles like “The Red Scare in the United States” and “The Red Scare Leads to Raids on ‘Subversives’.”

The climate of repression established in wartime continued. “The mobilization of the municipal police forces, state militias, and federal courts against strikers was but part of a larger post war business–government offensive against radicals and labor militants.”

The hunt for subversives climaxed with the Palmer raids under the direction of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer and his assistant, a young J. Edgar Hoover.

“In November 1919, Palmer’s agents arrested 250 members of the Union of Russian workers, beating up many though recommending only 39 for deportation. The next month 249 aliens were shipped off to the Soviet Union. Most of never been charged with a crime. Some, like the well-known anarchist Emma Goldman, had been in the United States for decades.”

But Palmer overplayed his hand. He warned that the nation faced a wave of violence by revolutionary communists May 1, 1920. Police were mobilized, buildings guarded and politicians protected, but when nothing happened on May 1st, the anti-red drive began to die down. Until 1924, however, the Department of Justice continued its antilabor activities.

Eugene Victor DebsIf there is one link between the strikes in the 1890s, World War I and the period after the war’s end, it is the socialist, activist, union leader Eugene Debs. In the years after Debs emerged from a 6-month prison sentence in 1895, he ran for president five times (in 1900, 1904, 1908, 1912, and 1920) as the candidate of the American Socialist Party. He did not win, but each time he ran, he got more popular votes than the time before.

Fortunately, Debs’ role as a presidential candidate is mentioned in most textbooks. In 1920, he ran while he was in prison for his opposition to WWI. He had been convicted of having violated the Espionage Act by, essentially, urging American workers not to kill European workers. This is from the speech, for which he was jailed. It was delivered in Canton, Ohio on June 16, 1918:

In the Middle Ages when the feudal lords . . .concluded to enlarge their domains, to increase their power, their prestige and their wealth they declared war upon one another. But they themselves did not go to war any more than the modern feudal lords, the barons of Wall Street, go to war… The working class has never yet had a voice in declaring war. If war is right, let it be declared by the people – you, who have your lives to lose.

When the jury found him guilty, he was sentenced to ten years. “Newspaper editorials across the nation cheered his conviction. The case went to the Supreme Court, which ruled in 1919 that expressing sympathy for men who resisted the draft made Debs himself guilty of the same offense.”

To understand the history of American labor students must know the life and legacy of Debs.

Post WWIAfter the war, the ceaseless efforts to maximize revenue by the owners of capital continued just as workers continued to demand union recognition, shorter hours and better conditions. According to the Gilder Lehrman Institute, “Over 4 million workers – one fifth of the nation’s workforce – participated in strikes in 1919, including 365,000 steelworkers and 400,000 miners.”

But conditions had changed; production levels were falling and millions of men who had been in the military reentered the workforce. Racism, fear of immigrants and fear of radicals played into the hands of capital and business was able to turn back the 1919 labor offensive.

As the working-class labor movement lost momentum and industrialization boomed , the attention of the textbooks turns almost exclusively to other issues, some caused by that rapid industrialization: unsafe consumer products, environmental damage and corruption in public life.

Labor Issues Leave Center StageIn the 1920s, about 25 percent of jobs were in agriculture, 40 percent were in manufacturing and many were in other blue-collar fields including mining and construction. Only about 5 percent of workers held what were considered professional jobs.

Nevertheless, virtually all textbooks shift attention seamlessly as if “reformers” simply got tired of dealing with labor. This reflects, at least in part, the problem of chronological history jumping from one thing to another. The result is that students seem encouraged to be finished with one topic and move on to another.

Every textbook I’ve seen labels the years between 1901 and 1921 the “Progressive Era” with a focus on “three progressive presidents.”

Historian Jill Lapore writes that “Progressivism had roots in late 19th century populism; Progressivism was the middle-class version: indoors, quiet, passionless. Populists raised hell; progressives read pamphlets.” Rest assured that history textbooks never contain sentences that entertaining.

The populist movement began before the 20th century. It favored the common person’s interests over those of the wealthy and argued that the federal government was complicit in the consolidation of power in the hands of big banks, big business and big railroads. Most populist support came from western farmers.

Progressives, who drew support from a middle class interested in furthering social and political reform, championed many of the same causes as populists, but while populists generally wanted less government, progressives wanted more, seeking solutions in reform legislation and in the establishment of bureaucracies, especially government agencies.

While some of the reforms pushed by progressives did make conditions of the working class better, that was never their focus. No dramatic overhaul of the distribution of wealth or control of the economy was high on their agenda.

The greatest failure of both the populists and the progressives was in mutual “acquiescence in the legal and violent disfranchisement of African Americans.” In general, both were uninterested and unwilling to address Jim Crow.

Turning from Labor to “Normalcy” and Popular Culture

In 1921, Warren Harding became the President. According to one textbook, he understood that “Americans overwhelmingly desired peace and quiet.”

Then, after mention of Harding’s election the next thirty-five pages drift to Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, temporary isolationism, Henry Ford, business consolidation, consumer culture, social trends, the Charleston and the stock market crash in 1929.

As a summary of that same decade nothing is more fitting than a line from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel “The Great Gatsby,” “They were careless people, Tom and Daisy – they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.”

Depression and the New DealOnce I built a railroad, made it run, made it race against time.

Once I built a railroad. Now it’s done. Brother, can you spare a dime?

– Yip Harburg

“Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?”

The programs of the New Deal are extensively described in every text I’ve worked with. There is no reason to go into those details here, but a summary might be of use. In the early years, the most prominent include restructuring the banking sector and increasing business regulation. The Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) was meant to help farmers by reducing crop production and raising prices.

Then, in 1935, the Administration introduced more legislation which included the Works Progress Administration (WPA), putting millions of workers to work. The National Labor Relations Act (also known as the Wagner Act) was also introduced, guaranteeing the right of workers to organize unions and bargain collectively.

Of course, it is essential that FDR get credit for breaking with the American tradition of government hostility to workers and unions. But workers all over the country also deserve credit for remaining militant.

Lorena Hickock was a reporter hired by FDR’s administration to report on social conditions. She warned of a problem if action was not taken and she cautioned that, “vast numbers of the unemployed in Pennsylvania are ‘right on the edge’ … it wouldn’t take much to make Communists out of them.”

Howard Zinn observed that the New Deal’s early program, “was aimed mainly at stabilizing the economy, and secondly at giving enough help to the lower classes to keep them from turning a rebellion into a real revolution.” And he posed an interesting question when he wondered if “Roosevelt and his advisors were aware that, in 1933 and 1934 measures had to be taken quickly to wipe out the idea that the problems of the workers could only be solved by themselves?”

John Burke, head of the Pulp and Paperworkers’ Union, reported in 1933 that he had “never known a time … When there has been so much discontent among the working people in our industry.”

The actions of various elements of this working class helped push the Roosevelt Administration in the right direction. They are what is missing from textbooks. Here are a few examples:

In the early years of the Depression, people all over the country organized spontaneously to stop evictions. In Seattle, the fishermen’s union caught fish and exchanged them with people who picked fruit and vegetables, and those who cut wood exchanged that.

“Perhaps the most remarkable example of self-help took place in the coal District of Pennsylvania, where teams of unemployed miners dug small mines on company property, mined coal, trucked it to cities, and sold it below the commercial rate. By 1934, 5 million tons of this “bootleg” coal were produced by twenty thousand men using four thousand vehicles. When attempts were made to prosecute, local juries would not convict, local jailers would not imprison.”

Unfortunately, it is also important to recognize that more could have been accomplished. Even state approved textbooks recognize that the New Deal did not offer an equal deal to minorities and women.

According to “History Alive!,” the New Deal may have offered some hope to minorities, but agencies “…continued to practice racial segregation, especially in the South, and FDR himself failed to confront the evil of lynching.” After all, Black soldiers continued to be segregated in the military.

And it was President Roosevelt who signed Executive Order 9066 forcing the internment of Japanese during WWII.

What Should be Done?As I have mentioned, in order to do justice to the history of labor, textbooks must take the time necessary to define terms carefully and explore issues in depth. This argues against a strict chronological structure.

In simple terms, a comprehensive exploration of important subjects, like the labor movement, should not be interrupted by prohibition, flappers or the Charleston. Those fighting for justice, no matter what their ideological identity, should not be dismissed by being swallowed up by a “Red Scare.”

Perhaps the publishers of new high school textbooks might consider breaking up the chronological outline to include short essays by individual historians that could develop a theme without interruption.

Perhaps the textbook narratives could be supplemented with an interactive searchable timeline that would allow students to visualize the connections between and among these topics and allow access to primary source documents and media.

All that would introduce a real sense of continuity which would greatly enhance the ability of students to understand subjects that stretch over decades like labor, immigration, systemic racism, the political use of Red Scares and immigrant baiting, the treatment of the Indigenous tribes, or the evolution of women’s rights.

None of what I’ve suggested has been unnoticed. In 1935 Langston Hughes wrote a poem suggesting what ought to be done:

Let America be America AgainI am the poor white, fooled and pushed apart,

I am the Negro bearing slavery’s scars.

I am the Redman driven from the land,

I am the immigrant clutching the hope I seek –

And finding only the same old stupid plan

Of dog eat dog, of mighty crush the weak.

I am the young man, full of strength and hope,

Tangled in that ancient endless chain

Of profit, power, gain, of grab the land!

Of grab the gold! Of grab the ways of satisfying need!

Of work the men! Of take the pay!

Of owning everything for one’s own greed!

O, let America be America again –

The land that never has been yet

And yet must be – the land where every man is free.

This is part two of Jim Mamer’s Missing Links in Textbook History Labor series. Check out part one, which focuses on labor events prior to World War I here.

https://scheerpost.com/2023/10/17/missing-links-in-textbook-history-labor-from-world-war-i-through-the-new-deal/

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....