Search

Recent comments

- figurehead....

2 hours 17 min ago - jewish blood....

3 hours 16 min ago - tickled royals....

3 hours 24 min ago - cow bells....

17 hours 16 min ago - exiled....

22 hours 18 min ago - whitewashing a turd....

23 hours 17 min ago - send him back....

1 day 47 min ago - the original...

1 day 2 hours ago - NZ leaks....

1 day 12 hours ago - help?....

1 day 13 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

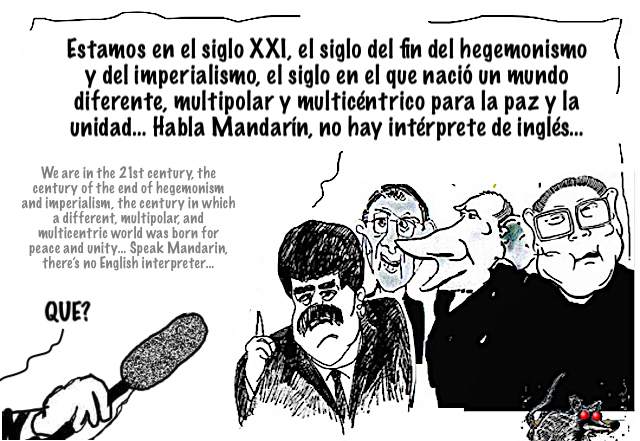

un mundo diferente en el horizonte.... 地平線上的另一個世界.....

Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro brushed off a question asked in English at the end of his visit to Beijing, telling the reporter to speak Chinese instead.

“Speak Mandarin, there’s no English interpreter,” Maduro cut off a reporter from Hong Kong. “It’s a new world!”he added. The exchange was captured on video and quickly made rounds on social media.

“We are in the 21st century, the century of the end of hegemonism and imperialism, the century in which a different, multipolar, and multicentric world was born for peace and unity,” Maduro said at the press conference, according to the Venezuelan broadcaster Telesur.

The Venezuelan president was wrapping up his six-day visit to China, aimed at improving the “strategic partnership” between the two countries. On Wednesday, he met with Chinese President Xi Jinping and signed over 30 working documents, ranging from trade to energy cooperation.

https://www.rt.com/news/582979-maduro-china-english-banished/

- By Gus Leonisky at 16 Sep 2023 - 5:23am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

communist capital....

China, innovation, and competition with the US By Paul MaloneThe real American terror is not that the Chinese economy will grow bigger than the American economy – if it is not already – but that the Chinese mixed economy model will prove superior to the rampant free-market, greed model US billionaires and their peddlers promote.

Western journalists and commentators have long struggled to explain how the Chinese economy actually works.

Typically we read of the failures under Mao’s communism and the explosion of growth with the supposed introduction of capitalism after the death of Mao and the rise of Deng Xiaoping. Before Deng we are reminded of the failures of the great leap forward and the disastrous cultural revolution. Little or no credit is given to, for example, the communists’ achievement in land reform, or educating the population, two essential ingredients in modernising an economy.

And Western commentators repeatedly tell us that the Chinese economy is about to collapse. (See for example: Gordon Chang’s 2001 book, The Coming Collapse of China; hedge fund manager, Jim Chanos’ 2010 description of China as being “on a treadmill to hell”; George Soros’ 2014 observation that China’s growth model had “run out of steam”; Morgan Stanley’s and Ruchir Sharma’s 2016 pronouncement that China now faces “the curse of debt”; and finance journalist Dinny McMahon’s 2018 observation that the economy was becoming “increasingly dysfunctional.”)

Now a new book, The New China Playbook: Beyond Socialism and Capitalism by insider Keyu Jin provides real insights into how the Chinese economy actually works. Jin, an associate professor at the London School of Economics, was born in China and is the daughter of Jin Liqun, an economist who previously served as vice-minister of finance.

The growth of China challenges Western capitalism’s claim of economic superiority. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union it’s been an article of faith that the “free market” is superior to planned economic systems. American capitalism won the economic race that began in 1917 with the Russian revolution and the formation of the USSR in 1922. The race “proved” that capitalism generated innovation and faster economic growth, albeit with inequitable share of the spoils.

But did it? Was it ever a fair race? Was it more a case of one competitor starting poor and crippled from the impact of war; having both legs broken along the way by a second war; and having post-war growth slowed by the burden of competing arms manufacture in its run to the finishing line?

In the next lane, the US started the race in the prime of its life; waited until the end of World War I before joining; suffered no World War II mainland invasion; and capitalised on the war’s destruction of Europe and Asia.

The end result was capitalists’ claim that “free markets” were superior to planned, or guided economies. Planned economies, it was said, simply could not compete.

The rise of China seriously challenges that claim. The bubble must surely be about to burst.

As the growth continues, Western commentators tell us that the Chinese system is oppressive and opaque: Xi Jinping and a small cabal of yes men dictate everything that happens in China.

Now Keyu Jin provide us with some insight into how the country actually works. She says the Politburo’s Standing Committee, which consists of the most important officials in the country, functions like a senior management team of a giant corporation. At the next level down, power splits into two branches, with the party on one side and the legislature and government on the other. Jin likens this structure to a double helix that converges at the top.

Municipal government has both a party secretary and a mayor, working closely together with the party secretary invariably ranking highest.

But unlike the centralised Soviet Union, local officials in China’s provinces and towns push their own agenda for local development and growth. The “Mayor Economy” has transformed fishing villages and backwaters into modern export hubs, manufacturing centres and high-tech economic zones. Local governments can give out licences, contracts, cheap land, and direct loans from local banks to firms they prefer. They can make new laws or sidestep the old and they can lobby the central government.

It is no accident that all three general secretaries of the Chinese Communist Party since Deng Xiaoping were once provincial leaders.

Since Deng’s reforms of the 1980s the structure of the economy has changed dramatically. Today the private sector employs around 80 per cent of the urban labour force.

Reforms initiated in the mid-nineties resulted in the shut-down, or privatisation of many state-owned firms and a consequent dramatic improvement in performance of those that survived. Large State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) became profitable and productive.

Today the SOEs play an important role in the economy, not only acting on their own behalf but also in collaboration with the private sector. In 2019, 63 of China’s 100 largest corporations were state players and most interestingly every single one of them had a joint venture with a private company.

In times of crisis, SOEs have also proved most useful. In the wake of the 2008-9 financial crisis they were called upon to salvage the economy.

Jin tells us that regions compete with each other and that at times local officials have bent, or even broken rules and traditions. In the 1980s, for example, when private sector companies might bear the stigma of being seen as “capitalist” they could be dressed up as collective enterprises.

But as the population and the central government came to see, ‘rule bending’ can go too far. In 2013 Xi launched a sweeping anti-graft campaign, resulting in 2.3 million officials being punished for violating party rules, or state laws. Among them was Zhao Zhengyong, the former party secretary of Shaanxi Province, who built expensive villas on protected land.

Unlike the USSR, China is not seeking to push an international ideological agenda. The government is seeking to maintain stability and lift the population’s standard of living.

But increasingly politicians in the United States – always in need of a barbarian to generate fear – have demonised China.

The US/China rivalry reached a peak with the election of Donald Trump in 2016. Covid-19 was sneeringly called the China virus; US unemployment was due to unfair Chinese trading practices, requiring tariffs to protect American jobs; and US technology transfer must be stopped.

President Biden has followed Trump, imposing export controls to cut off China’s access to top AI chips made by US firms such as Nvidia, Advanced Micro Devices and Intel.

The real American terror is not that the Chinese economy will grow bigger than the American economy – if it is not already – but that the Chinese mixed economy model will prove superior to the rampant free-market, greed model US billionaires and peddlers promote.

Educated in China and the US, Jin appears to accept the argument that innovation requires a private sector generating huge financial rewards for innovators. She seems to be unaware that many of the “zero-to-one” early-stage discoveries in the West were made in government run, or funded, institutions.

The most obvious examples in the US are the Manhattan project and the NASA moon landing. Computers were not invented by Steve Jobs, or Bill Gates. The internet is not a Google or Meta creation. It emerged from action to enable government researchers to share information. Major breakthroughs in medicine, such the discovery of Penicillin, have come from salaried researchers, whose reward is the discovery itself and perhaps recognition of their achievement.

China now aims to achieve break-throughs in key technologies: the central government has outlined the plan and local governments have been called upon to deliver.

Jin says China is building a fully integrated incubation chain, linking key national labs, universities and high-tech parks. Researchers from abroad are returning to China.

It is not until the end of her book that Jin addresses the question of rising inequality. Around the world, labour’s share of national production is declining, while capital’s share is rising. With the world’s second-largest number of billionaires, China’s inequality is now approaching that of the United States.

Jin writes approvingly of China’s efforts to eliminate illicit income, but says that not all income inequality is unjust. The problem she avoids addressing is that of increasing wealth inequality. She disapproves of ideological solutions by which she really means Communist ideology, implicitly accepting American ideology.

At some point Socialism With Chinese Characteristics is going to have to tackle the inequity/billionaire problem. In time ‘legitimate’ billionaires and their heirs become as damaging as illegitimate billionaires, wielding undue influence, consuming excessive amounts of resources and, contrary to their own propaganda, proving no better at planning and distributing resources than salaried managers.

Around the world, over the years the extremely rich have shown no loyalty to their nations, shifting their wealth at the hint of any fair redistribution. Perhaps Chinese billionaires can be persuaded to voluntarily relinquish their billions; maybe effective gift and death duties can be introduced. But one way or another, this issue will have to be tackled.

https://johnmenadue.com/china-innovation-and-competition-with-the-us/

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....

9/11 chile....

Overthrowing Allende: Australia’s special role in destroying a democracy

By Binoy Kampmark

Every September 11, those in the United States mourn the 2001 attacks that reduced the Twin Towers to rubble and holed the Pentagon. Some 3,000 people perished. US President George W. Bush declared in a speech following the attacks that the US had been targeted for being “the brightest beacon for freedom and opportunity in the world.”

Another September 11, as worthy of commemoration, saw the extinguishment of a democracy at the encouragement of that said “brightest beacon” in 1973. Five decades ago, the socialist government of Chile’s Salvador Allende was overthrown by a CIA-sponsored coup that saw the instalment of the butcher General Augusto Pinochet. National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger had warned US President Richard Nixon that the Allende government had to be removed, given its “insidious model effect” that could be emulated by other nation states. An insidious military dictatorship of sadistic propensity was far more preferable.

In an all too familiar pattern, a country unequivocally aligned to the security interests of Washington also weighed in this effort to destroy a Latin American democracy. In December 1970, at the urging of the CIA, Liberal Party external affairs minister William McMahon granted approval to the Australian Secret Intelligence Service in December to open a station in Santiago. ASIS, for its part, admitted that “there was no vital Australian political or economic interest in Chile at the time”. To this day, the role of that station and Canberra’s broader policy of disrupting and meddling in the affairs of Chile has never been acknowledged. Efforts to investigate and expose that role have also been frustrated, either at the level of declassification or via standard journalistic channels.

In 1983, Australia’s Attorney-General Senator Gareth Evans told the Senate that there was “no foundation for any suggestion that Australia in any way assisted any other country in any alleged operations or activity directed against the Allende regime.” Clyde Cameron, a former Minister for Labor and Immigration in the Whitlam government, almost fell off his chair on hearing the news.

In an interview with the ABC Four Corners program, and a letter, Cameron revealed being baffled on becoming Minister for Immigration in 1974 that the department had been providing generous overseas cover for 19 full-time Australian Security and Intelligence Organisation agents. “I was further advised,” wrote Cameron, “that one of these so-called migration officers had been operating in and out of Santiago around the time of the military coup which murdered the democratically elected President of Chile.”

The letter went on to disclose that Prime Minister Gough Whitlam had informed Cameron that he was aware of ASIS involvement in Chile. Cameron’s own investigations also found that his “ASIO ‘migration’ officer, together with ASIS, had acted as liaison officers with the CIA which masterminded that coup.”

The official position taken by Evans in the Senate jars with the 1977 admission by then opposition leader Whitlam to the federal parliament “that when my government took office Australian intelligence personnel were still working as proxies and nominees of the CIA in destabilising the government of Chile.” The remarks were made in the context of leaks from the first 8-volume secret report, authored by Justice Robert Hope as part of the Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security surveying the conduct of Australian intelligence activities.

To this day, the full extent of Australia’s Chilean operations in the report remains classified. Not even Brian Toohey and William Pinwill’s otherwise magnificent Oyster: The Story of the Australian Intelligence Service, sheds light on the precise details of the Santiago activities. Gareth Evans, this time as foreign affairs minister, would later directly intervene via the Federal Court in 1988 to suppress relevant unvetted material on ASIS’s role.

In 2015, SBS journalist Florencia Melgar began poking around in the murky depths of Australia’s Chilean chapter, spurred on by her story that Adriana Rivas, a former Pinochet intelligence agent residing in Sydney, was wanted by Interpol for the kidnapping and disappearance of seven members of the Chilean Communist Party. Melgar’s formal request to the Australian government to investigate ASIS’s role in Santiago was curtly dismissed. It was also accompanied by a diabolical, if incongruous statement, that publishing material on the subject, even if sourced from Chile’s Foreign Affairs official records, risked a legal prosecution.

In 2017, Clinton Fernandes of the University of New South Wales, along with barrister Ian Latham and solicitor Hugh Macken, collectively sought to declassify documents relevant to Australia’s Santiago station. In September 2021, the National Security Archive, an invaluable forum for intelligence documentation hosted by George Washington University, published a selection of Fernandes’s findings.

The documents note McMahon’s collusion with the CIA by offering up Australian agents while also documenting the operational and logistical problems of the station. In June 1971, a highly placed Australian official, whose name is redacted, even wondered about, “The need to go ahead with the Santiago project at all, at this stage.” The “situation in Chile has not deteriorated to the extent that was feared, when we made our submission”. But ASIS officials, their functions having been almost entirely outsourced to the CIA, would hear none of it.

The election of Labor’s Gough Whitlam spelled an end to the adventure, though by then the damage had already been done. In April 1973, he quashed a proposal by ASIS to continue its clandestine outfit, feeling, as he told ASIS chief William T. Robertson, “uneasy about the M09 operation in Chile”. But in closing down the Santiago station, he did not, according to a telegram from Robertson to station officers sent that month, wish to give the CIA the impression that this was “an unfriendly gesture towards the US in general or towards the CIA in particular.”

Five decades on, some parliamentarians have called for a formal acknowledgement of Canberra’s role in the destruction of a democracy that led to the death and torture of tens of thousands by a brutal military junta. The Greens spokesperson for Foreign Affairs and Peace, Senator Jordon Steele-John, stated his party’s position: “50 years on we know Australia was involved, as it worked to support the US national interest. To this day, Australia’s secretive and unaccountable national security apparatus has blocked the release of information and has denied closure for thousands of Chilean-Australians.”

In calling for an apology to the Chilean people, the Greens are also demanding the declassification of any relevant ASIS and ASIO documents that would show support for Pinochet, including implementing “oversight and reform to our intelligence agencies to ensure that this can never happen again.”

One decent reform comes to mind: serving the Australian people rather than the interests of a foreign power....

https://johnmenadue.com/overthrowing-allende-australias-special-role-in-destroying-a-democracypic-salvador-allende/

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....

truth decay.....

Australia’s secretive defence establishment: the real enemies of truth and freedom

By Jack Waterford

Australia, with fewer secrets to hide, is more compulsively secretive than the US, China or NATO.

General Angus Campbell is concerned about “truth decay” and artificial intelligence, worried that eventually citizens of this country will be unable to sift fact from fiction. Countries such as Russia were using disinformation as a weapon of statecraft in America and Britain, and engaging in campaigns that could increasingly be used to fracture “the trust that binds us,” he told a seminar organised by Australian Strategic Policy Institute last week.

I share some of his concerns but, while thinking him sincere, consider he has a bit of a hide saying this. There is a serious problem with foreign propaganda and discerning the truth in the modern world. But the biggest part of the problem, and the starting point for considering what we may do about it, is the public’s incapacity to know, understand or believe anything much that the Australian government, and the Australian Defence Force, puts out about defence matters. It is rather more difficult to sort truth from fiction supposedly coming from the enemy when one has no idea about the reliability of what we are being told by our own. And not much reason to believe anything much they say either.

There are different facets of the problem. There are leaders such as General Campbell himself who are deeply opposed to allowing the media, or other independent observers, anywhere near Australia defence forces in combat zones. Even if many of our defence writers are very gung-ho about war, its toys and our leading defence personalities, many have little security consciousness and might well unwittingly give away important tactical information in battle situations. Or, alternatively, the enthusiastic coverage might nonetheless convey critical information to other players in the game of statecraft.

General Campbell, for example, got his first big lift-up in 2013 when new Immigration minister Scott Morrison wanted a three-star officer to lead a military response to boat people. It consisted first, of trying to repel asylum seeker on boats back to the country from which they had departed, usually Indonesia or Sri Lanka. If the interception and the push-back failed, the operation, known as Sovereign Borders, was to convey the asylum seekers to foreign concentration camps, where they were to be held either until some other nation would take them, or the detainees gave up and asked to be repatriated.

A secretive defence establishment does not promote a well-informed and engaged citizenry

Freshly given his third star, General Campbell, against what I have been explicitly told was defence department advice, “suggested” to his minister that all interception operations be clothed in utmost secrecy. The argument was that people smugglers were very astute observers of Australian political and military events. They read signals, especially signals about Australia’s resolution to carry on. The best tactic was to deny them as much information as possible, preventing them from deducing the presence of Australian naval or border patrol ships, or the intelligence they were using, from the sky, on the ground, and from communications interceptions.

Being able to refuse to discuss all operational aspects of boat repulsions and interceptions – including often even the fact that they had occurred – suited the political interests of the Abbott government to a T. It knew that the invasion of asylum seekers – which it was trying to dehumanise by falsely calling them illegal entrants – was popular, to a point in the community. But it knew that the population would become increasingly squeamish if they were allowed to understand just how Australia was rounding up ships and dragging them back to where they came from. The Campbell “on-water matters” alibi was critical to the success of Operation Sovereign Borders. But that was not because it put people smugglers in the dark. It was because it put Australians in the dark.

It is curious that even now, 10 years after these deeds done in Australia’s name, there has been no official account, or critical inside review of what occurred. The secrecy has extended longer than after WWI or II, Korea, or even Vietnam. Defence doesn’t seem comfortable about its place in history anymore. Australians must suspect that the official histories of Australia’s participation in post-1990 wars in Iraq and Afghanistan will be critical of whether our participation made any positive difference to the (unhappy) outcomes. Not a single communique from the front, and hardly a single speech from an Australian senior official would be of the slightest use in making such an assessment. All that material, other than reports of deaths in action, was short on fact or verifiable information, and long on propaganda, unjustified optimism and wind. And if it was much better informed by journalism on the ground, whether by Australians or others, that mostly occurred without much help from the Defence Department.

But there are at least some records of these two ill-fated military adventures against which a temperature can be taken. The official history of Operation Sovereign Borders will have few facts, other than self-serving “official” facts to be checked against other evidence. No doubt many of the sailors involved did what they were told in an exemplary way, just as the soldiers involved in the Intervention into Aboriginal communities in 2006 and 2007 did. But that does not tell us anything of what was achieved, whether it was worth the cost, and whether everything that happened, including intelligence operations on the ground, involved things of which Australians can be proud. My strong suspicion is that the chronic secrecy hides a lot of official guilt.

The same attitude of mind in Defence can be seen over the prosecution of David McBride for betraying national security secrets. McBride saw evidence that ADF people, including SAS soldiers, were committing war crimes in Afghanistan. He did everything he could to draw it to attention through the “right channels” without going public. He was finally persuaded either that senior commanders and defence and intelligence officials either did not care or were more concerned with covering matters up than taking proper action. At that stage, he became an external whistleblower, by giving his evidence to the ABC, putting the matter in the public domain. It was only later that the creaky defence machinery, moving at glacial speed without evident enthusiasm, was seen to be responding. And it was years and years before the public was to discover, officially through an investigation headed by General Paul Brereton that there was substance in the allegations, and that they seemed to have been systemic rather than very rare exceptions. Even more alarmingly, many of the Australian officer class engaged in Afghanistan were blissfully unaware of what junior soldiers were doing but were effectively covering it up by furious denials that anything wrong had, or could have, occurred. It involved military mismanagement right up to commander levels.

McBride did not leak sensitive secrets of state, vital to protecting our national interest. He leaked evidence of malfeasance and murder, after his superiors seemed to be refusing to do anything about it. In that sense, he is more the hero than a good many officers given awards for their leadership in Afghanistan. But he gets no credit from the ADF establishment, nor from the defence and national security bureaucracy. Nor from its legal bureaucracy, right up to the Labor Attorney-General, Mark Dreyfus, who has tried to market himself as a supporter of whistleblower legislation, but who has refused to intervene in how his department is managing the prosecution. Dreyfus, apparently, is worried that dropping national security prosecutions, even for dodgy cases, might send a message around that the government does not take seriously the protection of secrets that matter.

McBride’s revelations may have done short-term damage to Australia’s international reputation, and the standing of the ADF among Australians. But the truth would have emerged ultimately anyhow, because far too many knew the shameful story. Our allies knew, not from the information swapped between allied officers, but from alarmed reports from their own military and intelligence systems. In the long run, it will have done us more good, in national and international standing, that we are now, albeit 10 years later, trying to address the problem rather than continuing to cover it up. Likewise, one of the few officers who smelled a rat, Captain Andrew Hastie (now a Liberal MP) deserves more credit for his sense of honour in pursuing his suspicions than most of his colleagues, who, though responsible for their men, were ignorant or didn’t want to know.

Australia, with fewer secrets to hide, is more compulsively secretive than the US, China or NATO

These are but two examples of the open-government instincts of the defence department. Whether as an armed force, or as a military bureaucracy, it is more compulsively secretive than any of Australia’s allies, including Britain, the United States, and NATO. Other defence organisations train and trust their agencies and officials to engage with the general population, and to participate in debates on policy and strategy. They do not routinely censor anything emanating from within their departments capable of suggesting that there are different points of view, that there are live debates about strategy and tactics. The virus has now also struck our politicians with Anthony Albanese being, if anything, more secretive than Scott Morrison, most recently on a climate change report. In Australia, many FOI requests are stymied. It is virtually impossible to get unsanitised administrative detail about procurement stuff-ups, or about the unhealthy and unregulated revolving door between officials, officers, defence industry and consultants.

Much the same problem occurs once one attempts to factor in the defence work of national security agencies. One good example of where Australians miss out might be seen from a recent paper on China issued by the Intelligence and security committee of the British Parliament. The 207- page report (isc.independent.gov.uk) deals with how and why the British intelligence establishment regards China as the greatest national security threat it faces, even though it admits that Britain is only incidentally in China’s sights. It discusses what it thinks to be China’s aims and ambitions, and why Britain is of interest to China. It discusses China’s search for political influence and economic advantage, and the whole-of-state approach of China’s intelligence services, its alleged involvement in human espionage and its cyber operations. It discusses alleged efforts to influence or interfere with government, elections, the media and the Chinese diaspora in the UK. It gives a case history of attempts to get involved commercially in the British civil nuclear energy sector that shows open investment activity accompanied by some clandestine interventions. It also deals at some length with how the British government and its intelligence establishment are dealing with some of the problems.

One should not be too surprised that there is little explicit discussion of AUKUS, of nuclear submarines of technology exchange, whether with Australia or the US. That’s because the assessment that China is an ultimate enemy does not depend on particular Chinese belligerence or its rearmament, but a deduction about its being an enemy because of its commercial ambitions, its recognition that America and China are in fundamental competition, and the threat the US could pose to China’s central consideration: the maintenance of the power of the Communist party. Even those who doubt that China is planning war on the US, or that it will act against Taiwan or in the South China sea that will cause war, might find little to disagree with about the security assessment. That China spies on its neighbours, its avowed enemies, and its commercial partners occasions no great surprise. The US, Britain, Australia and a host of others spy on China too. We all affect to dislike spying on us, and express horror at the idea that some of our citizens might be assisting them, or might, for their own commercial reasons, support some Chinese aims. Some of these might cross the line into espionage – the conscious handing of security sensitive information to a foreign power. But not every exchange of commercial or political information is intrinsically treacherous, regardless of what the Director-General of ASIO might think. Nor is everyone who doubts his apocalyptic warnings or his judgment an agent of influence.

Likewise, there has always been a good deal of open American military and intelligence material of a sort that would be routinely classified in Australia. One will, for example, easily find out more about Australian defence procurements from open-sourced assessments by the US General Accounting Office (equivalent to our national audit office) and the congressional reporting service than is ever published by government in Australia. As often as not, Defence will be obdurately resisting FOI or other disclosure on national security grounds even after it is shown to be published in America. This is never to keep knowledge of it from a potential enemy; it is to keep it a secret from Australians.

Relentless propaganda against China and preparing the ground for war

A third sort of knowledge vacuum and risk from misinformation, disinformation and outright lying comes from establishments inside the military and intelligence system that devote their activities towards propagandising for war and an extremely hawkish attitude towards China. It is not merely a matter of persuasion about the soundness of nuclear submarines or other defence equipment for Australia’s defence needs. It is about creating a climate of opinion in which Australia identifies its interests as being America’s and shares right-wing American perspectives and intentions about China. There are ideologues in Australian government who are, for all intents and purposes, agents of the US with transferred loyalties.

As General Campbell comments, healthy and functioning societies such as ours depend upon a well-informed and engaged citizenry. But we are increasingly living in a post-truth world where perceptions and emotions often trump facts. He said that Russia had wielded disinformation “as a weapon of statecraft in the lead-up to the 2016 US election and the Brexit referendum. What set Russian campaigns apart was the use of novel technologies to enhance the scale, speed and spread of their efforts.

“By feeding and amplifying untruths and fake news on social media via the use of bots, troll farms, and fake online personas, the Russians attacked American and British democracy, highlighting distrust, sowing discord, and undermining faith in key institutions,” the Guardian’s report of his speech said. Such operations had “the potential to fracture and fragment entire societies so that they no longer possess the collective will to resist an adversary’s intentions.”

True, no doubt, but he is almost certainly understating what we do to ourselves. Most of the fake news in circulation in the US – feeding, for example, conspiracy theories about vaccines and stolen elections – is home grown, not of Russian or Chinese origin. The major damage being done to western institutions has been the conscious work of people such as Donald Trump, Boris Johnson, and Scott Morrison. The distrust, discord and loss of faith which is so evident is not to be laid at the doors of our international enemies, real or imagined. A good deal of the local effort in breaking down institutions has been the conscious effort of ideologues trying to impose smaller government and operating with neoliberal economic theories.

Anyone wanting a sample of what we ourselves can do, need consider only arguments and misrepresentations coming from the referendum on the Voice. I have not heard it suggested, even by the usual suspects, that they are being framed in Beijing or Moscow, or even Washington. Pogo once declared that “we have met the enemy and he is us.” In the battle for truth and open and accountable government, General Campbell might be better focused on getting Australia’s house in order rather than in imagining any Australian capacity to reform and transform our enemies. It could be his Glencoe.

https://johnmenadue.com/australias-secretive-defence-establishment-the-real-enemies-of-truth-and-freedom/

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....