Search

Recent comments

- dumb blonde....

1 hour 53 min ago - unhealthy USA....

2 hours 26 min ago - it's time....

2 hours 48 min ago - pissing dick....

3 hours 7 min ago - landings.....

3 hours 18 min ago - sicko....

16 hours 7 min ago - brink...

16 hours 23 min ago - gigafactory.....

18 hours 10 min ago - military heat....

18 hours 52 min ago - arseholic....

23 hours 36 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

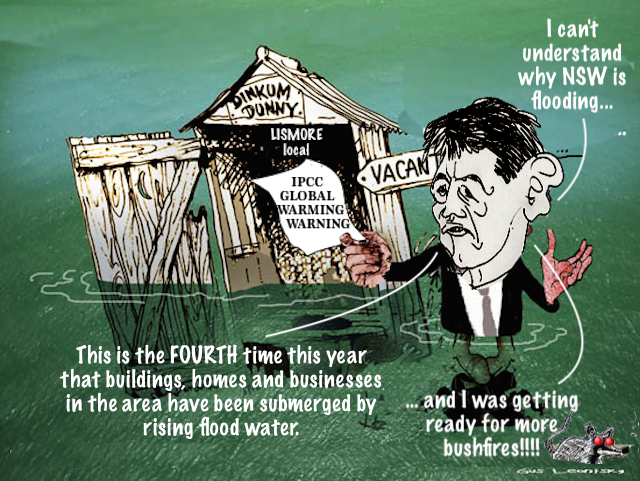

getting wet feet without knowing why…..

After former Energy Minister Angus Taylor expressed shock at the current flood devastation, Greenpeace CEO David Ritter explains why it wasn't hard to see coming.

HEY, ANGUS TAYLOR, you look surprised by the catastrophic flooding events. Can this be because you have been ignoring the warnings about climate change impacts? Here's a dozen or so expert warnings about increases in storms and floods that you may have ignored.

BY David Ritter

The truth is that we have long known, for decades, that for each degree that our atmosphere warms, it can hold 7 per cent more water. This causes heavier rainfall and in turn, increased flood risk.

Fourteen years ago, in 2007, the Rudd Government commissioned the Garnaut Climate Change Review, which clearly identified that climate change would lead to ‘longer dry spells broken by heavier rainfall events’ and floods.

So, in other words, when the Coalition came back into government under Tony Abbott in 2013, the memo was waiting for you: climate change is going to bring worse flooding.

Jumping to October 2014, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s seminal fifth assessment report highlighted Australia is one of the developed world’s most climate-vulnerable nations and that vulnerability included increasing catastrophic flooding impacts as climate change worsened.

In January 2015, scientists warned that La Niña events, a weather phenomenon linked to increased rainfall, would occur almost twice as often this century as the previous due to climate change. So more flooding is likely.

In 2016, the Department of Energy and the Environment’s State of the Environment report highlighted that variable rainfall levels and more intense storms, combined with sea-level rise, would make coastal storms and floods even more damaging and frequent.

In 2018, the Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO’s State of the Climate report highlighted that because of climate change, Australia would experience increased intense heavy rainfall throughout the country — so more flooding.

Specifically, the report noted:

‘As the climate warms, heavy rainfall is expected to become more intense, with short-duration extreme rainfall events (most closely associated with flash flooding) showing a larger than 7 per cent increase.’

This also found the NSW coast is particularly subject to compound events – extreme rainfall, storm surges and low-pressure systems occurring together causing extreme coastal inundation – with climate change making compound events more frequent and intense.

In 2018, Queensland’s Chief Scientist noted:

‘The future is likely to see an increase in flood risk due to climate change.’

The government in which you were serving as Minister for Energy and Emissions Reduction was told in the 2020 State of the Climate report that climate change is leading to more intense, rapid heavy rainfall — resulting in more intense and damaging flooding.

Last year, experts warned publicly that catastrophic flooding events were now more likely due to the impacts of climate change.

A report released by the Australian Academy of Science in the same month highlighted that without urgently reducing emissions, at scale, storms and flooding would violently reshapeAustralia’s coastlines and communities.

In November 2021, then-Senator Rex Patrick revealed that the National Cabinet had received a briefing about Australia’s 2021-22 high-risk weather season that was kept confidential. The higher chances of dangerous flooding was a focus of the briefing.

Apart from the expert warnings, there have also been, actual real-time floods for three years in a row. The warnings have literally been manifest before your very eyes, but you seem to have ignored this, too.

Lest we forget...

In early 2020, just as the catastrophic bushfires began to ease, Australia’s east coast experienced record flooding events, with Sydney facing the heaviest rainfall in 30 years.

In March 2021, NSW faced another catastrophic flooding event, with 10 million Australians under weather warnings, huge areas declared disaster zones and 18,000 people evacuated.

As then Premier of NSW Gladys Berejiklian said:

“I don’t know any time in state history where we have had these extreme weather conditions in such quick succession.”

A study of the March 2021 Sydney floods found the probability of similar weather conditions that caused the catastrophic flooding, known as “atmospheric rivers” were increasing based on our current emissions pathway.

After these devastating floods, scientist Dr Joelle Gergis, a contributing IPCC author, noted:

‘So while Australia has always experienced floods, disasters like the one unfolding in NSW are likely to become more frequent and intense as climate change continues.’

Then there was March this year, when parts of Queensland and New South Wales were again smashed by intense flooding. You were still in government then, so I assume you got the briefings on cause and effect.

So mate, as you stand under your umbrella looking out at the destruction, why don't you have a long think about how you might dedicate your time in Opposition to shifting your party's slavish support for the coal, oil and gas vested interests that are driving climate chaos.

David Ritter is the chief executive officer of Greenpeace Australia Pacific. You can follow David on Twitter @David_Ritter.

READ MORE:

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

- By Gus Leonisky at 7 Jul 2022 - 9:21am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

100 years, now every three months…..

Last Monday, a couple spoke to an ABC television reporter on the back steps of their home on the edge of Wollongong’s Lake Illawarra. They were confident that the flood they could see in front of them would not rise beyond the level it had reached. After all, they’d been living there for 19 years and no flood in that time had exceeded that level.

This reasoning is common and deeply flawed. It indicates how people are hard-wired to rely on their own experience and how little they understand, trust or rely on forecasts from authorities. It also shows how poorly people comprehend extremes in nature and how far beyond recently-experienced events nature can go in terms of severity. This goes for bush fires, floods, storms, tropical cyclones, storm surges, droughts, earthquakes, plagues and all the other perils of nature.

Not as infrequently as might be imagined, records in nature are not just beaten, they are beaten by large margins. A resident of Nyngan in 1990, having lived there for the hundred years of Nyngan’s existence to that time, could have been excused for thinking he’d seen all that floods could throw at the town. But the flood of that year peaked a metre higher than any flood previously experienced at Nyngan – and that in an area seemingly completely flat as far as the eye can see in almost all directions. The flood of 1990 brought four and a half times the amount of water through and past Nyngan than had been recorded in any previous flood there.

Or take Lismore at the end of February this year. The two highest floods of living memory, which struck in 1954 and 1974, had peaked at 12.1 and 12.2 metres respectively. This year’s event peaked at 14.37 metres – or more than two metres higher than the two biggest floods previously seen there. The record, established over the 150 years of Lismore’s history as a town, was smashed not by a little but by a lot.

In appreciating nature, we must think of the long term. This is not the period of one’s tenure in a location, or even the period of one’s life. We must think centuries, not decades, let alone years. And we must recognise how often, given the short period over which our records have been kept, records are broken. Indeed in 2007, a drought year in most of Australia, flood height or rainfall intensity records were set at some location or locations in every state. Sometimes, the new records beat the old ones by considerable margins.

Sooner or later, people in any location will see an extreme event: you only have to live long enough. But equally, you may not live long enough to see anything truly extreme. The other way of putting that is to say that some generations never see a genuinely extreme event whereas other generations might be unlucky enough to see one – or indeed more than one.

Take Maitland, on the floodplain of the Hunter River. Maitland was first settled by Europeans in 1818. In 1952, the highest flood recorded since that year struck – and it was eclipsed by a much larger one within three years. The 1955 flood peaked almost a metre higher than the flood of 1952 and was vastly more damaging.

The residents of Kempsey in 1949 saw the highest flood ever known there – and then the following year they saw a flood nearly as large. Thus the two biggest Macleay River floods of Kempsey’s history occurred within ten months of each other.

Grafton, on the Clarence River, tells an opposing story but one which also carries a cautionary message. Grafton has had many floods in its 180 years, but its biggest six have all been within half a metre of each other in terms of peak heights. When the authorities fifty years ago were contemplating constructing levees and calculating how high they should be built, they ‘deemed’ the then-record flood of 1890 as the ‘one-in-100-years’ event and the standard to which the levees should be constructed. That flood peaked at 7.9 metres on the local gauge, and the levees were built to that height plus 0.3 metres ‘freeboard’ to counter any inaccuracy in the estimate of the 100-years flood.

Unlike Maitland, Nyngan and Lismore, Grafton has not yet had an ‘outlier’ flood, a flood far bigger than any other seen there. It follows that Grafton’s biggest floods have all been of a magnitude that occurs quite frequently – perhaps of the order on average of only 20 years. The ‘on average’ is vitally important here: nature is not regular in these things. Grafton, in all likelihood, has not had a flood of genuinely extreme proportions.

This is shown by the fact that the ‘one-in-100-years’ event at Grafton is now thought likely to reach something like 8.35 metres. Today’s levees, designed to keep out what was originally considered to be a relatively rare event, might actually be expected to be overtopped quite frequently. Indeed Grafton has had four ‘close shaves’ in floods since the year 2000. The 7.9 metre flood, once thought to approximate the 100-year event, might in fact be more like the 20-year one.

The ‘one-in-100-years’ designation is dangerously flawed, though, and ideally the term should be discarded. It misleads people into thinking that having seen a flood of a size deemed to be a ‘one-in-100-years’ event they will not have to face another flood of similar proportions in their lifetimes. But it is not true that such a flood will not occur for another 100 years. A flood of that size or larger should more properly be regarded as having a 1% chance of occurring or being exceeded, each and every year, at any designated location (such as Maitland, Nyngan or Grafton).

The best way to refer to it is as a 1% AEP (Annual Exceedence Probability) event: this is the arithmetic reciprocal of the so-called 100-year event. In actuality, a flood of this size or larger could occur on a number of occasions in a 100-year period or not at all for several centuries. In these matters (unlike the seasons or the diurnal cycle of day and night), nature does not like regularity.

The so-called ’20-year flood’, accordingly, has a 5% chance of occurring or being exceeded at a location in any year. Again, this is a statement of average. It does not follow that three floods designated as (say) 5% AEP events occurring at a place in quick succession (as Windsor has experienced since early 2021) invalidates the measure or the expression. Such variability is quite normal: Windsor had not experienced a flood as big as any of these three since 1990. The concept of ‘average’ is central here and there is variability, not regularity, around it. Windsor has just had a short (16 month) period of flood richness after a long period (30 years) of flood poverty.

Don Bradman averaged, in round terms, 100 runs per dismissal in Test cricket. He did not score a neat 100 in each innings. In fact he made several ‘ducks’ and many scores between 0 and his best of 334. He had sequences of low scores as well as periods in which he made several big scores in a row.

There are policy implications in all this. School classes in maths could teach probabilities using examples from occurrences of events in nature. Likewise courses in geography or science could deal with the matter.

And the emergency services should take the moment when a bad flood has just occurred as a ‘teachable moment’ to get the point across and educate the wider population: such a time is likely to be one during which the media will be attentive (and looking for new angles of coverage) and audiences will be listening and receptive.

The expression ’100-year flood’ has caused untold problems because it is so badly misunderstood in the community. And that is not its only deficiency: it is the basis in Australia for the designation of the minimum floor levels for new dwellings in flood liable locations. This too is a matter where it causes problems.

But that is something for another piece in Pearls and Irritations.

READ MORE:

https://johnmenadue.com/flood-misunderstanding-miscommunication-extremes-and-records/

READ FROM TOP.

And the wet and dry will be going to "more" extreme as the surface of the globe warms up.....

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW.....................@!@!@!@!!!!