Search

Recent comments

- a long day....

1 hour 22 min ago - pressure....

2 hours 10 min ago - peer pressure....

17 hours 28 min ago - strike back....

17 hours 34 min ago - israel paid....

18 hours 37 min ago - on earth....

23 hours 7 min ago - distraction....

1 day 17 min ago - on the brink....

1 day 26 min ago - witkoff BS....

1 day 1 hour ago - new dump....

1 day 13 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

the philosophy of sciences...

In philosophy we often travel with circular arguments at the start of which we have to make assumptions. The elasticity of these arguments make for the ebbs and flows of the questions that plague human nature and our busy-ness. We’re curious. But we don’t like not knowing. If we have no way of knowing, we invent a story, a reason, a purpose, a decree, a religious system. Science is a work in progress, and as explained in the attached comment, is an honourably self-correcting endeavour.

But there are many variation and human understandings of sciences. For Gus-the-old-kook, political sciences is an oxymoron. There is no science in politics, only artificial ways to apply a deceiving art form designed to convince more people of the worth of Swiss cheese. We could argue that we need social equality, but some people could counter-argue that this leads to welfare encouraging people to be lazy.

Thus we enter political arguments of relative values.

Sciences are far clearer on the observations and theories. But when these are applied to political decisions, the scientist’s mind can be clouded by money, political bias, hubris from prejudices and their own necessary scientific doubt.

An article in the Monthly Magazine, Australia, captures the idiosyncrasy of philosophy and our various attitudes to who said what — right and wrong… Here is the intro to this article about Christopher Hitchens, who we have often mentioned on this site:

On the question of why Christopher Hitchens still matters, Ben Burgis ultimately has little to say

In 2009, when I interviewed Christopher Hitchens in anticipation of his appearance at the inaugural Festival of Dangerous Ideas, I used our last 10 minutes together to ask his opinion of, among other things, Australian journalist John Pilger.

“I remember thinking that his work from Vietnam was very good at the time,” Hitchens said. “I dare say if I went back and read it again, I’d probably still admire quite a lot of it.” He proceeded to describe Pilger as unthinkingly anti-American, but it was the generosity of his preamble that struck me most at the time.

Such generosity has not, as a rule, been extended in kind to Hitchens. For his critics, at least on the left, there is little interest in returning to his work that predated September 11, 2001, and none at all in revisiting that which followed. Though there had been other, earlier disagreements, it was the attack on the Twin Towers and everything it precipitated, especially in Iraq, that came to define the man and his legacy. His unwavering support for the War on Terror was and remains a rupturing apostasy that colours the entirety of his output in either direction.

Ben Burgis’s new book, Christopher Hitchens: What He Got Right, How He Went Wrong, and Why He Still Matters (Zero Books), presents itself as an attempt to redress this. It is a book in the vein of Hitchens’ own slim volumes on Bill Clinton, Henry Kissinger and Mother Teresa – only, as I’m sure Burgis would concede, not nearly as eloquent. As an attempt to explain, if not to excuse, Hitchens’ position on the war in Iraq and to demonstrate the ways in which he otherwise remained a progressive, if not a socialist, until the end, it is relatively successful. As an argument as to why it still matters that Hitchens held any of these positions it is decidedly less so.

…

The fact is that Burgis’s subtitle is a bit of a false flag. Hitchens still matters because he still matters to Burgis, in the same way that Hitchens still matters to me. He matters to us because we came to him young, because he influenced our writing and the development of our ideas, and, as is so often the case with one’s heroes, because he ultimately disappointed us. He matters because all cautionary tales matter, and Hitchens’ final decade, in so many ways, was nothing if not one of those. I remember thinking that his work on the Reagan years, on Cyprus and Palestine and Kissinger and Wodehouse, was very good at the time. I dare say if I went back and read it again, I’d probably still admire quite a lot of it.

—————————————

Gus:

We’re not perfect beasts… Christopher Hitchens was not either. One thing for sure is that Christopher HATED religion. The attack on the Twin Towers was like a catalyst to hate Islam some more and anyone that could be blamed for it was it. At this level, Hitchens knowledge of history faded in the background of the will to “destroy Islam” by supporting Bush invading Iraq for good reasons in Hitchens’ mind… This of course was stupid. Iraq under the thumb of Saddam Hussein was like a cushion between the USA and Islam extremism. It would have been more beneficial for the USA to bomb Saudi Arabia, as most of the 9/11 culprits were Saudis/Sunnis and the Saudis are the least democratic fiefdom on earth.

So, on the issue of the Iraq war, Hitchens was stupid… But what we should remember Christopher Hitchens for is his PHILOSOPHICAL thoughts on the issue of religious beliefs and the clarity of his expressions on the subject. It seems that Matthew Clayfield has understood this, including the erroneous views of Hitchens of our national hero, John Pilger.

Ben Burgis is possibly going into vaguedom — that country where Dialetheism rein supreme and where black and white is always 50 per cent grey.

Dialetheism is the view that there are statements which are both true and false. More precisely, it is the belief that there can be a true statement whose negation is also true. Such statements are called "true contradictions", dialetheia, or nondualisms.

Ben Burgis is a serious satirists who indulges in Dialetheism… or what Gus calls "philosophical diarrhoea while drinking beer during a pub test".

Ben Burgis in his own words (I hope they are his?)

Ben Burgis, like Pac-Man and the Reagan Administration, came into the world in 1980. Ben grew up in a nice college town in the Upper Midwest, where he was raised by nice hard-working people who really can’t be blamed for the fact that their son writes about such upsetting things.

In 2003, he graduated from Aquinas College in Grand Rapids, Michigan, where even the one-two punch of virtue that is Grand Rapids and nuns failed to prevent him from spending most of his free time organizing anti-war protests and drinking whiskey with his Godless degenerate friends. After Aquinas, Ben moved to the hilariously-named city of Kalamazoo, Michigan, where he spent two years working on an MA in Philosophy at Western Michigan University. The best thing about Kalamazoo, apart from its name, is that it has the best deep-dish pizza place in the entire world, Bilbo’s Pizza in a Pan. The Hobbit Stix with dill dip are a thing of beauty. Eating their spinach-stuffed pizza with mushrooms is not unlike a religious experience.

Of course, due to his trips to Kalamazoo’s many fine used bookstores, Ben also spent those two years really digging into the works of Philip K. Dick and H.P. Lovecraft. From the former, he learned that nothing is the way it seems. From the latter’s stories of tentacled, gibbering gods of chaos and madness and bad dreams and non-Euclidean geometry, he learned that a religious experience might not be such a fun thing to have. That spinach-stuffed pizza, though, that’s good stuff.

Etc and on and on…

Ben Burgis does not appear to be a religious man, but he teaches philosophy at a “black” College…

Morehouse College is a private historically black men's liberal arts college in Atlanta, Georgia. Anchored by its main campus of 61 acres (25 ha) near downtown Atlanta, the college has a variety of residential dorms and academic buildings east of Ashview Heights. Along with Spelman College, Clark Atlanta University, and the Morehouse School of Medicine, the college is a member of the Atlanta University Center consortium. Founded by William Jefferson White in 1867 in response to the liberation of enslaved African-Americans following the American Civil War, Morehouse adopted a seminary university model and stressed religious instruction in the Baptist tradition.

So, what is all this about?...

The flexibility of arguments does not mean they have to be conflicting like matter and anti-matter. Anyway, in the event that they do, they still emit energy that will be captured by something/someone else. This is why our media are monolithic on certain issues. They don’t want to discuss the alternative options BECAUSE IN MOST CASES, the alternatives would be proven “more correct” than their biased hubris. The “biased hubris” pumped to 11 is designed to unite people to believe in the truthfulness of their governments implemented capitalist system. Any alternative would challenge this system.

Thus we don’t want to rock the boat… Thus the system will support the freedom of religion and let Christopher Hitchens' memory fall into the dungeon...

And atheism isn't a religion...

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW !!!!

- By Gus Leonisky at 13 Feb 2022 - 7:35am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

communicating sciences...

Amid the many miscommunications and misunderstandings about how to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists have been called on to do a better job of explaining their work to the public. In the United States, John Holdren, former science adviser to President Obama, has gone so far as to call for every scientist to become a trained communicator in an army of ambassadors for the whole country.

That all sounds good on the surface. But just what do we expect these scientific emissaries to accomplish? Is it education? Is it advocacy? Is it changing behaviors?

Media training for scientists has been fashionable for years. Private companies cash in on the trend. Universities regularly conduct science communication workshops for researchers. There are conferences on the science of science communication. Science journalists have written books about how to convey complex information to a general audience. What more can be done?

It’s not just a matter of translating jargon into plain language. As Kathleen Hall Jamieson at the University of Pennsylvania stated in a recent article, the key is getting the public to realize that science is a work in progress, an honorably self-correcting endeavor carried out in good faith. Moreover, scientists need to have some understanding of their audience to improve the chance of a true dialog. They may need to learn to listen and “read the room,” and prepare different approaches for different audiences.

Some communication lessons were learned, for example, by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2014 Tips campaign for smoking cessation. Rather than focusing on the data showing why smoking is dangerous, the campaign revolves around personal stories of patients who have suffered smoking-related illnesses that individuals can relate to. Application of this principle—which meets folks where they are rather than burying them with data—led to remarkable progress in smoking cessation. Understanding this is a high-level skill that requires expertise.

It is also the case that not every scientist wants to take time away from research to be a voice for science. Traits that make a good researcher, such as concentration on details and laser focus on a problem, don’t often carry over to the public stage. Most scientists prefer to persuade by performing meticulous, credible work.

I work with some of the best science communicators in the world, and I see how hard they have endeavored to hone their craft. This is a profession and a full-time job—not something that can be picked up in a workshop. Recently, I talked to one scientist who seems to succeed in wearing both hats. Rebecca Schwarzlose, an accomplished neuroscientist at the Washington University School of Medicine, wrote an outstanding popular book,

Brainscapes, about neural maps. Her training as both a scientist and communicator didn’t come easy. After getting her PhD from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Schwarzlose initially left the lab and became an editor at Trends in Cognitive Sciences. After hearing her give a talk to a general audience, I complimented her on the clarity of her message and asked her if she thought every scientist could do what she has done.

“No, I don’t,” she said. “I think what we should probably be aiming for is finding ways to give scientists tools to help them communicate, not necessarily even with a general audience, but just more broadly between different disciplines.” That sounds good, but it’s not the same thing as preparing a cadre of communicators to go to Kiwanis clubs full of climate deniers.

After talking to Schwarzlose, I think we need to be careful with the notion that every scientist can be easily trained to also be an outstanding communicator. You frequently hear the idea that a science communication course should be a required part of graduate training. This can’t hurt, but asking someone to be a skilled science communicator after taking one course is like asking someone who has taken a course in chemistry to discover a novel reaction.

Truly well-trained science communicators—individuals who devote their lives to helping the public understand research—deserve more respect from their research colleagues. As Schwarzlose’s story shows, it’s not something that just anyone can pick up quickly. Maybe a better idea is to figure out how to improve the partnership between researchers and these public communicators.

H. HOLDEN THORP

SCIENCE • 23 Dec 2021 • Vol 374, Issue 6575

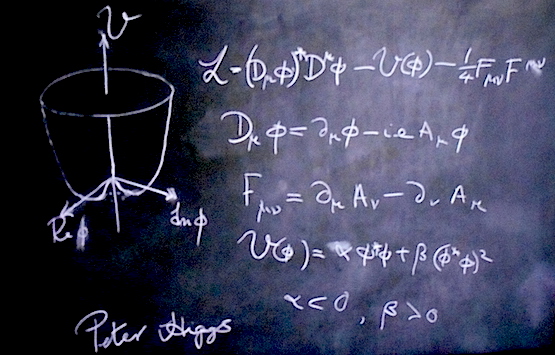

Note: Picture at top. Peter Higgs explained the Higgs (field) boson...