Search

Recent comments

- not peaceful....

1 hour 16 min ago - 25 big helpers....

1 hour 29 min ago - courage....

2 hours 42 min ago - going nuts....

3 hours 1 min ago - oily law....

3 hours 9 min ago - culprits.....

3 hours 51 min ago - criminal jew....

4 hours 25 min ago - gestapo....

6 hours 4 min ago - criminal....

6 hours 9 min ago - intensity....

11 hours 35 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

spilling the beans on "the dismissal"...

angleton

angleton As early as the 1960s, James Jesus Angleton insinuated that numerous Western leaders were KGB agents. The most famous allegations concerned the British Harold Wilson, the Swede Olof Palme, the Canadians Lester Pearson and Pierre Trudeau, and the German Willy Brandt. At one point, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger was also suspected by James, of being a KGB agent. This state of affairs created chaos in the CIA, paralysing many of its activities.

When Angleton also accused aides of President Gerald Ford, CIA Director William Colby received the green light to send "his almighty colleague" to retire on the spot, together with many of his collaborators. It took years to reorganise the CIA, including rebuilding its USSR Section — and find the real moles. Angleton died of cancer in 1987.

Angleton had friendly relations with Junio Valerio Borghese who was a “socialo-proto-fascist” in Italy… In the 1980s, US investigative journalist David C Martin provided many clues that Angleton had actually been a pro-Communist, including Angleton's friendship with Philby.

Without ever contacting the Russians, who “may" not have suspected Angleton was working for them, Angleton acted alone to destroy the CIA from within, with increasingly complex, paranoid and inefficient operations that generated chaos inside the Agency… The operations included recruitment of ex-Nazis, having exclusive relationships with Italy, Germany and Israel, reading all American correspondence with foreign countries, wiretapping all phone calls from East Berlin, continuously hunting for non-existent spies within the CIA, without ever finding the real ones... All real moles were eventually identified by other CIA offices. James has also been accused for the overthrow of Allende, but I believe this was done to taint him. This kind of dirty ops was not in his departmental briefs...

In 1977, James Jesus was interviewed by an ABC Australian news crew…

Here is the view (edited for clarity) from producer Andrew Leslie Phillips:

In May 1977 I received a call to come to the ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation) office in New York for an assignment with Australia’s top television documentary program, Four Corners. Ray Martin had landed an interview with James Jesus Angleton who had been head of counter intelligence at the CIA for twenty-five years. Angleton was ready to spill the beans on the CIA’s influence in sacking Australia’s Labor Party Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam. I’d heard speculation about CIA involvement in Australian politics but here it was from the horse’s mouth, from the man who knew the back-story.

Gough Whitlam was a charismatic, ambitious and intelligent politician, He was loved by the left and hated by the right. After twenty-three years of conservative government, in 1972 he became Prime Minister. In his first days in office Whitlam pulled Australian troops out of Vietnam and reinstated the passport of renegade Australian journalist Wilfred Burtchet. Burchett was demonised by the former conservative government and a pliant Australian media because of his left-wing leanings and highly critical reporting of the Vietnam War. It was a symbol of a new era. I was to meet Wilfred Burchett in Cuba some years later.

I was in Papua New Guinea in 1972 when Whitlam was elected and for the first time in my life felt an affinity toward the political process. At last Australia was showing backbone instead of knee-bending supplication to the American bully boys. It had been “all the way with LBJ”, as Australia followed America into Vietnam in the 1960’s and it sickened me. With Whitlam’s election it seemed Australia finally might stand up. The CIA quaked as Whitlam articulately outlined a new Australian independence particularly when it came to uncovering and expelling Pine Gap, the secret American communications node smack bang in the center of the nation and where no Australian was permitted.

Whitlam was brash and outspoken in his first years but gradually altruism turned sour and realpolitik kicked in. When the money supply was halted by a bickering parliament, government ground to a halt. The 1975 Australian constitutional crisis, commonly called The Dismissal, culminated with Prime Minister Gough Whitlam’s dismissal by the Queen of England’s Governor-General Sir John Kerr. Australia was part of the British Commonwealth and the queen is more than symbolic head of empire.

The queen’s Governor General appointed the Leader of the Opposition, Malcolm Fraser, as caretaker Prime Minister. It was the greatest political and constitutional crisis in Australia's history. The nation was still under the boot of the British imperium and in the pocket of America. I was disgusted. During the ABC interview Angleton outlined the web of CIA’s control. The revelations about the undermining of the Australian Labor government confirmed my worst speculations as I came of age in America.

A common allegation was the CIA influenced Kerr's decision to dismiss Whitlam. In 1966 Kerr had worked in intelligence and had joined The Association for Cultural Freedom, a conservative group funded by the CIA. Christopher Boyce was a young American employee at TRW and a CIA civilian contractor. He analysed data gathered by satellite. Like Edward Snowden, Boyce made public documents that revealed the CIA wanted Whitlam removed because he threatened to close US military bases in Australia. Boyce said the CIA described Sir John Kerr as "our man Kerr". These allegations were made in Parliament in 1986.

Boyce’s story became a book and a movie, “The Falcon and the Snowman”, by Robert Lindsey, a New York Times reporter. Boyce was later convicted as a spy. He was an anti-hero. The Australian journalist John Pilger called the dismissal a "coup". He alleged the CIA used the Nugan Hand Bank as a front to "set up” the Whitlam Government. Pilger alleged the bank provided slush funds to opposition parties in Australia and, with the CIA, undermined the Australian government, subverted trade unions and liaised with Governor General Kerr during the crisis. The bank was later revealed to be a handmaiden for the CIA.

Angleton was a staunch right-wing conservative who believed in American exceptionalism. He said he loved Australia and had great respect for ASIO, Australian Security and Intelligence Organization, and believed Australia to be a frontier nation. America sixty years ago. He seemed bitter and broken still smarting from his own dismissal from the CIA. he was not holding back. Angleton confirmed the narrative and Ray Martin, our reporter who later went on to host a popular, daily, national television talk show, peppered Angleton with questions in the ABC bureau on the 19th floor in the center of Manhattan in Rockefeller Center that day.

The CIA has a history of underhanded involvement in destabilising freely elected governments and Angleton was instrumental in destabilising socialist President Salvador Allende in a CIA sponsored coup in Chile, September 1973. His stories were mesmerising and I pushed my Sennheiser shotgun microphone closer to gather every syllable and speech mannerism and made sure the recording levels were perfect.

Before his dismissal, Prime Minister Whitlam charged publicly that American Intelligence organisations were secretly channeling funds to politicians who supported American secret bases in Australia. Whitlam demanded an investigation by the Australian Defense Department to identify, once and for all, the real purpose of the bases.

Pine Gap was located deep in central Australia collecting data from spy satellites. The base was an essential component of the America’s spy matrix. If shut down, American surveillance would be blind. Pine Gap in central Australia near Alice Springs was off limits to Australians. The base was considered American territory. Few Australians knew it even existed until Whitlam blew the whistle.

On November 11, 1975, a few days before I was to leave Australia for America, Prime Minister Whitlam scheduled a speech in which he was to discuss the CIA and the mysterious installations in the Outback. But he never had the chance to deliver it. On that day, Governor General Sir John Kerr removed him from office. Like others in Australia, I was outraged and depressed at his dismissal. It was one reason I decided to leave Australia. I felt the bitter taste of cowardice and shame, frustration and disappointment.

We concluded the first part of the interview with Angleton in the ABC’s Rockefeller Plaza bureau in New York and a few days later flew to Washington D.C to his home in the leafy suburbs of Virginia. When we arrived he was in his garden. Angleton could easily have stepped out of the pages of a John le Carré thriller and in fact subsequent films and television series used him as their model. He was tall and thin with a pronounced stoop. His face was angular and his thick grey hair was combed backward from his broad forehead. He wore heavy black-framed eye- glasses and a cigarette held delicately between two long fingers traced the air.

As a young man he studied at Yale and as an undergraduate edited the literary magazine, Furioso, which published many of the best-known poets of the inter-war period, including William Carlos Williams, e.e. cummings and Ezra Pound. He carried on an extensive correspondence with Pound, cummings and Eliot. We sat while his wife poured tea in fine china cups. There were orchids in pots near a window.

The investigative journalist, Jay Edward Epstein met Angleton and wrote of the spymaster’s fascination with orchids in a detailed diary entry. They sat together in the dining room at the Madison Hotel in Washington soon after Angleton had been fired by Director, William Colby.

“He was ghostly-thin with finely sculptured facial features set off by arched eyebrows. Throughout the evening, he drank vintage wine, chain-smoked Virginia Slims and coughed as if had consumption. A quarter of a century in counterintelligence had extracted some toll.

“And then Angleton talked about his love of orchids explaining that it was most deceptive orchid that survived. The perpetuation of most orchids depended on them misrepresenting themselves. Having no food to offer, they deceived insects to land and carry pollen to other orchids in the tribe.

“To accomplish this deception, orchids use colour shape and odour to attract insects to their pollen. Some orchids capitalise on the sexual instincts of insects. The tricocerusorchid so perfectly mimics, in three-dimensions, the underside of a female fly including the hairs and smell, that they trigger mating response from passing male flies. Seeing what it thinks is a female, the male swoops down on the orchid and attempts to have sex - a process called pseudo-copulation. The motion causes the insect to collect pollen and thus it becomes an unwitting carrier. When the fly passes another tricocerusorchid, they repeat the process, and pollinate another orchid.

“It gradually became clear that Angleton was not just talking about insects being manipulated through deception but an intelligence service being similarly duped, seduced, provoked, blinded, lured down false trails and used by an enemy.”

The term Angletonian entered the parlance as an adjective used to describe something conspiratorial, overly paranoid, bizarre, eerie or arcane.

When our interview was over we retired for a drink to review what just happened! We were in a state of mild shock. We knew we had a scoop and next day we packed the film for air express to Australia. It didn't make it.

It disappeared without a trace!

------------------------------

Gus: informations from “deep throat” characters indicate that some RIGHT-WING (Liberal aligned) managers at the ABC “spirited” away the rolls of films to never be seen again. Other sources would indicate the two-hour recordings over a four-hour stint never left the USA… Considering Angleton’s history, he would have been under CIA surveillance till he died. Anything to do with him would have been censored, “managed” and interviews would have been no-nos. Apparently, James had a daughter who, at the time of the interviews, seemed very hostile, belittling him, and she might have been the one who blew the whistle on James spilling the beans. Knowing that he himself could have been working for the KGB, revealing the CIA stint on Whitlam in a somewhat obtuse/obvious manner was possibly designed in his own mind to sink the CIA into deeper shit, as he himself had been retired from it in unceremonious manner, for having been “inefficient”…

In 1974, the missteps of Operations Chaos and HT-LINGUAL caught up with Angleton, when the New York Times investigative journalist Seymour Hersh made it known that he was writing an expose of these two government infringements on the rights of American citizens. Angleton was called into Director of Central Intelligence William Colby's office and advised that it was time for him to submit his resignation. Fervently believing that his work at the CIA wasn't done, Angleton resisted, and in desperation he called Hersh and tried to bribe the reporter with promises of other classified information if he buried the story he was working on. Hersh recalls that conversation with Angleton, and in Cold Warrior he describes Angleton as being "off the reservation" and "totally crazy." The article was published, and the backlash was, as expected, damaging to the agency.

Angleton put off his advised retirement for months, and even after he had submitted his letter of resignation, he continued to show up for work as usual. This continued for months until he finally resigned himself to his fate in the spring of 1975.

That the CIA pushed Whitlam out of the Australian government, is a given nonetheless… That the GG, Kerr, was working for the Americans — despite his letters to the Queen — can be assured… and Malcolm Fraser played along, probably without knowing what was happening. Later on, Fraser despised any Australian government sucking up to the Yanks, having possibly realised too late the CIA deceitful stunt on Whitlam... and on Australia in general... Malcolm Fraser would HATE THE PRESENT LIBERAL PARTY, that is bordering on FASCISM, while clowning in front of the people, to distract us from its nasty bend in its heart.

-------------------------

Links to various sources available...

If Angleton's work was to destroy the CIA, he did this as much as he possibly could...

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW NOW NOW !!!!!!

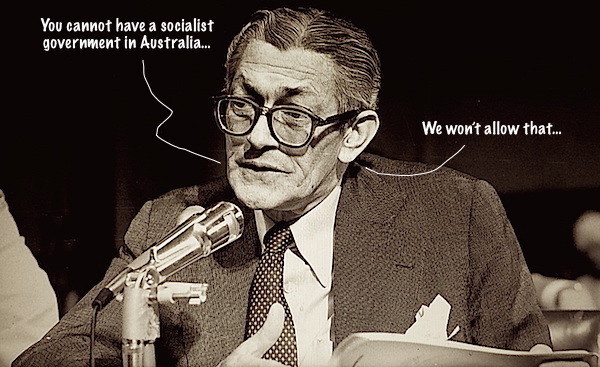

Words in the picture at top, "quoted" as remembered by the recordings that vanished... Angleton's words mimicked the CIA's, rather than his own beliefs, obtusely...

Devious and accurate to the hilt...

- By Gus Leonisky at 7 Dec 2021 - 1:23pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

a note to young and old australians...

1 — Presently the Liberal (Conservative) government is trying to destroy the ABC.

2 — The ABC has done tremendous programs that exposed the trickeries of governments, left or right

3 — FAR LESS than other news network, the ABC can do a few mistakes that can be rectified easily

4 — The ABC is the most trusted news network in Australia

5 — The Murdoch media hates the ABC because of this, and because the Murdoch media is incapable of not being biased on most issues.

6 — The ABC provides many services that are unsung, but extremely valuable at all echelons of society

7 — As well as being news and entertainment savvy, the ABC also provides philosophical platforms

8 — SBS also provides a tremendous service — unequalled on the planet...

9 — The Liberals (Conservatives) allied with the IPA and News Corp (Murdoch media) have decided in their policies to:

a) privatise the ABC and SBS.

b) and/or destroy the ABC and SBS.

c) do it slowly by reducing the budgets till both organisations are bled of talents and unable to perform essential services...

d) accuse the ABC of bias when the ABC is often more right-wing than left-wing, but not ultra-right-wing...

The importance of the ABC cannot be sung enough. Young people grew either on the ABC's homegrown children programs or on the commercial American shit (sorry big bird)... This is why the ABC audience needs to be alerted to the IPA, Murdoch and Liberal not so secret alliance designed to kill off the ABC. The Friends of the ABC do a great job at promoting the ABC — and it's also up to the younger generations to hold the flame for the national PUBLIC BROADCASTERS — ABC and SBS — both unique gems in the world of news, entertainment and social awareness.

Thank you.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW........

the mole....

In late 1986, it became apparent to anyone in Langley that the CIA was on the verge of a catastrophe. For years preceding the fateful moment, the Soviet KGB had been suspiciously successful in identifying, arresting and executing double agents recruited by the agency in the USSR. The uncomfortable truth was that the CIA had a mole within its ranks. When it became apparent, the manhunt for one of the most destructive and highest paid spies in American history began.

Deadly trapIn 1985, Oleg Gordievsky, acting head of the KGB cell in London, received a panicked telegram from Moscow. He was ordered to return to the Soviet capital. Being a double agent working for MI6, Gordievsky had his reasons to disobey. However, he decided to take the risk of returning to Moscow, where he was later drugged and interrogated.

This was a time when the CIA was losing assets to the KGB, one by one. High profile figures in Soviet security agencies and scientific institutions were handpicked by the KGB counterintelligence with terrifying ease. Death awaited those who were caught spying for the U.S.

By 1990, the CIA virtually stopped recruiting new double agents in the USSR, because the list of its acting agents was vanishing like sand through fingers. Unless the leak was identified, the CIA had no means to protect its assets in the USSR.

The mole huntDesperate to find the culprit, the CIA assembled a mole hunt team consisting of veteran CIA employees. Consisting of three gray haired women and two men, the team looked nothing like the spy hunters portrayed in movies, but it had all the means and expertise to uncover the origin of the deadly leaks that plagued the agency.

Although it was possible that the KGB had obtained access to the CIA documents or communications through bugs, the mole theory made the most sense.

In the course of their investigation, the mole hunt team was diverted from the right course multiple times. At first, the KGB ran a misinformation operation, which led the team to believe the mole was stationed at Warrenton Training Center, a classified CIA communications facility in Virginia. The mole hunters investigated over 90 people stationed at the facility, without definitive results.

The team came by the next red herring, when a source volunteered information that the KGB had penetrated the CIA with a mole who was born in the USSR. None of these was true, allowing the evasive mole to operate unpunished.

Soon, the mole hunt team comprised a list of all people who had access to the information that had been revealed to the Soviets. “We knew which people had the best access. So, we were able to weed down the list by the level of access the person had in addition to other considerations,” said member of the team Jeanne Vertefeuille.

Eventually, the list was reduced to 28 people. If there was a mole in the CIA, he or she was on the list.

The team began making the suspects take polygraph tests. One of the examined employees was CIA officer employed in the CIA’s Soviet/East Europe Division Aldrich Ames. He successfully passed the polygraph test twice.

A devastating divorceAldrich Ames started career in the CIA in 1962. He married a fellow officer Nancy Segebarth, who subsequently resigned to abide by the CIA rule that prohibited spouses from working from the same office.

READ MORE:

https://www.rbth.com/history/335924-aldrich-ames-cia-mole-soviet-ussr-kgb-spy

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....

JJA downfall......

Seymour Hersh: The Fall of James Jesus AngletonBy Seymour Hersh / Substack

This piece is from Seymour Hersh’s Substack, subscribe to it here.

Last week I wrote a column about my unforgettable afternoon visit more than a decade ago in London with the late Pervez Musharraf, the exiled Pakistani president who bragged to me about his country’s ability to hide its nuclear arsenal deep underground. Two days later, my colleague Jeff Stein, whose SpyTalk newsletter covers American intelligence, turned over his column to Jefferson Morley, an author who has spent decades tracking the CIA and other state secrets stemming from Jack Kennedy’s assassination onward.

Morley focused on the Biden administration, battered anew last weekend in the wake of negative polling, and its willingness to continue pretending that Israel, long known to have an undeclared but significant nuclear arsenal, has no such arsenal. His main target was the administration’s refusal to declassify 48-year old Senate testimony by James Angleton, the notorious onetime head of CIA counterintelligence. Angleton turned up recently as a character in A Spy Among Friends, a television series about the murderous transgressions of Kim Philby, the brilliant British intelligence officer who spied for the Soviet Union and conned Angleton, among others, in a long career of betrayal.

After serving in the Office of Strategic Services in World War II, Angleton was assigned as station chief for the newly organized CIA in Rome, where he had two main responsibilities: he was liaison to the Israeli nuclear program and was the main architect of the CIA’s postwar mission to prevent Italian politics from turning to the left after years of fascist suppression under Benito Mussolini. Instead, the CIA supported the two most prominent anti-communistgroups in Italy: the Mafia and the Christian Democratic party. Political corruption was a staple of life in Italy for the subsequent decades.

I have a few things to add to Morley’s account.

Support our Independent Journalism — Donate Today!SUBSCRIBE TO PATREONDONATE ON PAYPALMusharraf’s contempt for US efforts to monitor and, in his view, control Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal stemmed from his knowledge of America’s policy of denying that Israel was a member of the world’s nuclear club. In the 1970s and ’80s, various administrations ignored Congressional pressure to cut off American foreign aid to nations that sold or received nuclear processing or enrichment materials, equipment, or technology. The law was enforced, however, two times for Pakistan but for no other nation, including Israel.

In early 1978, President Jimmy Carter continued to look past the Israeli arsenal, but he did send Gerard C. Smith, his ambassador-at-large for nonproliferation issues, to meet with Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, the Pakistani president, to discuss secret Pakistani plans to build a nuclear arsenal. I was later told by George Rathjens, Smith’s deputy, that Zia, who had fought in the Second World War with the British Indian army, responded by asking Smith why he was not also talking to Israel. Smith was upset, Rathjens added, “but there was no way to answer Zia. No satisfactory answer. The Israeli bomb wasn’t anything people [in the Carter Administration] wanted to talk about. It was an embarrassment.” Rathjens went on to become one of the founders of MIT’s Securities Study Program and continued his research in nuclear disarmament.

In 1972, I left a swell job with the New Yorker at the urging of Abe Rosenthal, the cranky and politically conservative editor of the New York Times, to join its Washington bureau and, Abe promised, to write the truth about the Vietnam War as I saw it. He made it plain that he knew something was missing in the newspaper’s coverage. It didn’t take me long to understand why Rosenthal was troubled. I was part of the bureau’s foreign policy cluster, and, soon after we got to town, my wife and I were invited to a dinner at the elegant home of the paper’s senior diplomatic correspondent. It was there that I met James Angleton, who was at the time, as I would learn more than a year later, in charge of the agency’s illegal domestic spying program. He also was a big part of Washington’s Old Boys network. It was not merely a cliché. After the meal was served, the women were invited to gather together in an anteroom while the men attended to business. I still remember the look on my wife’s face.

Such ties were then part of the foreign policy reporting game. Henry Kissinger was always available for a few Times reporters, with the proviso that his comments were never to be directly quoted. CIA Director Richard Helms was part of the crowd, too. My beat focused on Vietnam, but I was soon running into Washington spy stories that were just begging to be told. I knew I would need a large chunk of time off after I informed the bureau chief in the fall of 1972 that I had been chipping away on three major stories: the CIA’s active role in undermining the socialist government of Salvador Allende in Chile; the planned recovery of a Soviet submarine that had broken apart, with at least three nuclear torpedoes on board, in the Pacific Ocean; and the CIA’s spying on thousands of American antiwar dissenters who, so President Lyndon Johnson believed, were being directed by Soviet operatives.

It was a month before I got approval in writing to continue my reporting. I was urged by a senior editor to put all I knew into one general story about the needs of America’s national security community to conduct sensitive foreign and domestic intelligence operations that sometimes crossed the line. I was also urged to “touch base” with Kissinger and Helms. I was shocked. At that point, I saw no other recourse than to resign from a dream job. Rosenthal got wind of my discontent, and I was told in advance about a change soon to comein the bureau’s leadership. In a few months, my new boss would be Clifton Daniel, a senior editor in New York—and the husband of Margaret Truman, daughter of President Harry Truman. Daniel called me in Washington, told me not to quit, and promised he would “have my back.”

Daniel did have my back. I was off the leash, with the support of many in the Washington bureau. The brilliantreporters there included the likes of Johnny Apple, John Herbers,Elaine Shanahan, John Finney, and Christopher Lydon. Russell Baker, Anthony Lewis, and Tom Wicker were columnists. Watergate was a consuming issue at the time, thanks to the work of Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward in the Washington Post, and the Times seemed lost. I stayed as far away from that story as I could, and continued to chip away at Vietnam. Helms was quickly removed as CIA director and sent to Tehran as US ambassador to Iran. The new director was William Colby, an old hand who had flown behind enemy lines for the Office of Special Services during the Second World War and had recently been running the CIA’s controversial and murderous Phoenix Program in South Vietnam.

It took me more than a year to break the stories I was working on because in late 1972 Rosenthal insisted I drop my investigations and cover Watergate. With Nixon on the ropes in early 1974, I was able to slide back into the blockbuster story, about which I had told few specifics to Rosenthal or any other editor on the paper. By then I had reason to believe from my sources at the agency that it had been spying on Americans in direct violation of its charter prohibiting it from spying on citizens here. All roads led to my onetime dinner partner, James Angleton, head of counterintelligence.

A secret history of Colby’s tenure as CIA director was declassified in 2011, and it includes a chapter entitled “Seymour Hersh and His Charges against the CIA.” I learned from the report that the agency was tracking my reporting on its illegal abuses that I had begun on my own early in 1972. The agency had no way of knowing that I had no choice—that is, because Rosenthal gave me no choice. He switched my focus to Watergate and its messy aftermath for the next two years. By the fall of 1974, with Nixon on his way out, the report says, Colby “learned that Seymour Hersh was making inquiries about past CIA operations.” Written by an experienced covert operative, the report notes that I had learned that an internal review of illegal agency activities—known informally as the “family jewels”—had been put together in great secrecy. The report says Colby’s response was to instruct “all CIA deputies not to honor Hersh’s requests for an interview.”

But Colby kept on taking my calls that summer and fall, especially when he was told that I had mentioned the “jewels” in a conversation with Congressman Lucien Nedzi, a Democrat from Michigan who learned from me about the in-house nickname. Nedzi was then chairman of the House Intelligence Committee.

By this time, I was telling any of the senior CIA officials who took my calls that I knew Angleton was deeply involved in spying on Americans. I suspected that any CIA report focused on Angleton, even if called the “family jewels,” would be far from

complete. And so I sent a message to Colby, as included in the CIA history, saying, “I figure I have about one-tenth of 1 per cent of this story,” and added this snotty comment: “I am willing to trade with you. I will trade you Jim Angleton for 14 files of my choice.” The report says Colby was “perplexed” by the message. But I doubted it when the report was declassified in 2011, and I doubt it now.

In December of 1974, when I knew I had a story of massive violation of the CIA’s charter, I talked again to Nedzi. And so did Colby. A transcription of that conversation was published in the CIA study and from the first question on, it is priceless:

NEDZI: I talked with him [Hersh] a short time ago . . . who is Jim Angleton?

COLBY: He is the head of our counterintelligence. He is kind of a legendary character. He has been around for 150 years or so. He is a very spooky guy. His reputation is of total secrecy and no one knows what he is doing. . . . but he is a little bit out of date in terms of seeing Soviets under every bush.

NEDZI: What is he doing talking to Hersh?

COLBY: I do not think he is. Hersh called him and wanted to talk with him, but he said he would not talk with him.

NEDZI: Sy showed me notes of what he said and claims he [Angleton] was drunk.

COLBY: You catch me twelve hours ahead of an unpleasant chore of talking to him about a substantial change of his [Angelteon’s] responsibilities.

NEDZI: There is a bit of a problem for you. What occurs here is all of a sudden a guy is telling me things about—and he is going back to that meeting we had in which you briefed me on all of the—he used the same terms, incidentally, “jewels.”

COLBY: Hersh did?

NEDZI: Yes.

COLBY: I wonder how he got that word. It was used by [only] a few people around here.

NEDZI: The problem that occurs to me right now is that here is a guy [Hersh] who is trying to expose the agency and all of a sudden he [Angleton] gets sacked.

COLBY: Yes, what I think I will do is talk to Hersh . . .

I did talk to Colby at length and very carefully about the CIA’s domestic spying, which, as I later learned, involved keeping more than 100,000 files on antiwar protesters. I told him that in one of my talks with Angleton he claimed that the domestic spying operation was run by one of his deputies and he had little to do with it. He told me about what he said were two ongoing CIA covert operations: one inside Russia and the other in North Korea, whose details would make terrific stories. All I had to do, he said, was drop any mention of him in my domestic spying story. I relayed all of this to Colby and told him my story would be in print within days.

When the story was published on December 22, 1974, it was roundly denied by CIA spokesman and repeatedly attacked as dead wrong by the rival Washington Post for the next three months. It was only when Colby was called before Congress’s Church Committee in 1975 that any official acknowledged the general truth of what I had reported.

Splashed across the paper’s front page, my 7,000-word dispatch didn’t name any of the seven CIA sources I quoted, one of which was Colby. I stayed friendly with him after he left the CIA, until his death in a boating accident in 1996.

The establishment of the Church Committee in 1975 was the direct result of my story and its follow-ups. Its hearings and papers provided the most detailed examination of the CIA and its activities to this day. I don’t think we shall see its likes again. The Democrats in the White House and in Congress have shown no interest in trying to learn what the agency and other US covert operatives have been doing on the ground in Ukraine or under the waters of the Baltic Sea.

© 2023 Seymour Hersh

NOTE TO SCHEERPOST READERS: We are happy to be able to run some of Sy Hersh’s pieces from his new Substack venture. Please, if you can, sign up at seymourhersh.substack.com so you can support Sy Hersh’s work and the ability to bring it here on ScheerPost. Thank you!

READ MORE:

https://scheerpost.com/2023/05/12/seymour-hersh-the-fall-of-james-jesus-angleton/

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....

a CIA job....

“Shame Fraser, shame”: The overthrow of Edward Gough Whitlam

By Jon Stanford

Nov 8, 2023

When offered the position of Governor-General by Prime Minister Whitlam in 1974, Sir John Kerr consulted friends and colleagues as to whether he should accept the appointment. One of them, Justice Robert Hope, queried why he would take such “a dead-end job, a hopeless job.” Kerr’s response was: “Oh, no, it’s a very powerful position. It has much more power than you realise.” – Jenny Hocking, Gough Whitlam, Vol. II.

The dismissal of Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam by Queen Elizabeth’s Vice-Regal representative, Sir John Kerr, was an extraordinary event. For almost fifty years a debate has raged about why the Governor-General took the unprecedented action he did on 11 November 1975.

This five-part series focusses more on the external events leading up to the dismissal than on the domestic circumstances, which have generally been well rehearsed. The release of the Palace letters, achieved only after an extraordinary campaign by Professor Jenny Hocking, has added significantly to the knowledge bank. Yet, the letters were clearly written for the record, on the understanding that at some point they might become public. In one sense they are somewhat akin to Sherlock Holmes’ ‘curious incident of the dog in the night’. Like the dog, which ‘did nothing in the night’, the curious feature of the Palace letters is that they contain no reference at all to some of the most significant issues surrounding the dismissal.

Such omissions are valuable in themselves, however, because they prompt further investigation. Is it not strange, for example, that the Queen’s private secretary, Sir Martin Charteris gives Sir John Kerr the green light to dismiss the Prime Minister without ever exploring the reasons why Kerr is contemplating taking such an extreme step? All Charteris says, almost in a throwaway line, is that Kerr must be careful to justify the dismissal on constitutional grounds, before handing him a dodgy Canadian precedent to assist him in doing so.

This first piece in the series briefly covers the domestic events leading up to the denouement on 11 November 1975. In the subsequent four articles, the Whitlam government’s fraught relationships with the US Administration and the Five Eyes intelligence agencies are explored in terms of their possible significance in Whitlam’s downfall. In the final piece we also endeavour to piece the whole jigsaw together and identify the different forces that led to Sir John Kerr taking that unprecedented action on a glorious Spring day in Canberra all those years ago.

*****

In early 1975, despite the growing global economic problems, the Whitlam government was not in a bad position politically. In March, however, Malcolm Fraser successfully challenged Billy Snedden for leadership of the Liberal Party and Whitlam was now confronted with a far more dangerous adversary. Although Fraser suggested at the outset that he didn’t intend to follow his predecessor in threatening to defy constitutional conventions and deny the government supply in the Senate, he later qualified this undertaking. Now the government’s supply bills would only be blocked were any “extraordinary and reprehensible” circumstances to arise.

Although the government won sufficient seats in the Senate in May 1974 to pass its Supply bills, this situation changed in 1975. When Lionel Murphy, a Senator from NSW, was appointed to the High Court in February 1975 and a Queensland Senator died in August, they were not replaced by members of the Labor Party. By virtue of breaching a multi-party agreement honoured since 1949, the coalition now had the ability to deny supply.

By mid-year, pressure on Fraser to deny supply was steadily growing on the opposition benches but he was content to await the opportunity, as he put it, to “catch Mr Whitlam with his pants down”. In retrospect, this was an ironic ambition for a man who, eleven years later, appeared, sans culottes, in the foyer of a seedy Memphis hotel.

In October, the opportunity arose when the loans affair claimed its final victim. Rex Connor, Minister for Minerals and Energy, resigned for having misled Parliament. It was a relatively trivial offence, probably more of an oversight than anything else, but by the standards of the day Connor had to go. As one newspaper put it, Fraser now had discovered the “footsteps of a giant reprehensible circumstance” and on 15 October he stated that the Coalition would block supply in the Senate. Most of the media opposed him. An opinion poll at the end of the month showed that by a large margin the public disapproved of Fraser’s actions.

It is important to note that apart from the very poor process followed by the government, the loans affair was largely a storm in a teacup. No contract had been signed, no money had been borrowed and no commission had been paid. Nevertheless, although it was not a credible reason for denying supply, it provided cover for the broader concerns, ventilated particularly by the Murdoch press, regarding the government’s competence in managing the economy.

This was also largely a furphy. While admittedly both unemployment and inflation were increasing, this was a consequence of the first oil shock that was by no means limited to Australia. Bill Hayden had taken over from Jim Cairns as Treasurer in mid-year and his first budget had received widespread approval. Perhaps of greater significance is the fact that under the Whitlam government – in October 1974 and repeated in June 1975 — Australia received a triple A credit rating from the international agencies for the first time.

Even before Fraser made his move in mid-October, the Governor-General had clearly given a great deal of thought to his options should another crisis over supply emerge. In November 1974, at Rupert Murdoch’s residence in country NSW, over drinks and with journalists present, Kerr became somewhat indiscreet. He canvassed the available options, including dismissal, a discussion that would no doubt have been relayed to senior players in the opposition.

In September 1975, Kerr began to share his thoughts with Martin Charteris, the Queen’s private secretary. While it would be preferable for the opposition not to block supply, he suggested, ultimately it may be that only an election could resolve the issue. Then “if Mr Whitlam will not advise one, I might have to find someone who will”. That month, in discussion with Prince Charles in New Guinea, the Governor-General again raised the possibility of dismissing the Prime Minister.

On 30 September, Kerr advised Charteris that if supply were denied, the Prime Minister was considering an election for half the Senate. Even if he didn’t win additional seats, this could have the effect of temporarily giving Whitlam the numbers to secure supply. Charteris responded positively: “The Prime Minister’s new tactic seems to me to be much more reasonable and therefore more likely to be used. I imagine you would have no constitutional difficulty in agreeing to a Half Election of the Senate.”

This was the obvious way forward. Charteris clearly agreed with it. It remained an option in Whitlam’s back pocket until 11 November, when he was trumped by Kerr before he could exercise it. Later, in a statement that has never been taken very seriously but perhaps should have been, Kerr’s Official Secretary, David Smith, said that had Whitlam not gone to Yarralumla to recommend a half-Senate election, “the events of 11 November simply would not have occurred”.

To be sure, possible problems with the half Senate election soon emerged but these should not have been deal-breakers. It was not a popular option for the opposition, and it quickly became apparent that conservative premiers in some States might trample on another convention and instruct their governors not to issue writs for the election. Although, under s11 of the Constitution the election could still go ahead, with States participating or not as they chose, as Charteris was quick to point out, recalcitrant action on the part of some States could potentially cause problems for the Crown.

Under an anachronistic colonial legacy, in 1975 State governors represented the Queen of the United Kingdom, not the Queen of Australia, and were appointed on the advice of British Ministers. Were a State governor to resign rather than accept their Premier’s instruction not to issue writs, for example, as the NSW governor Sir Roden Cutler said he would, the Queen would have to appoint a replacement. The Premier would propose someone who would follow his instruction, but the Queen would not be bound to accept their advice. Either way, it seems inevitable that the Queen would have become involved in Australian politics.

On the same day as Fraser announced he would block supply, Sir Michael Palliser, Permanent Secretary of the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office, arrived in Australia. His objective was to safeguard the Queen from any involvement in Australia’s unfolding political crisis. Palliser held meetings with Kerr and Cutler. No record of the meeting with Kerr has been published. Nevertheless, we know that Palliser left Australia confident that the Governor-General would protect the Queen from any controversial involvement in Australian politics.

Given the detail that Kerr was conveying to Charteris at this time, it is remarkable that Sherlock’s dog fails to bark again – there is no mention of Palliser’s visit to Australia in the letters. Yet, if the Governor-General had indeed undertaken to protect the Queen from any involvement, it is difficult to see how he could do so. It was not within his jurisdiction to advise State governors or, indeed, the Queen on these matters. It is interesting, however, that no further mention of a half Senate election appears in the letters.

Up to the end of October, Kerr adopted a neutral tone in his correspondence with the Palace. It seemed clear his preference at this time was still for the Opposition to withdraw. He also proposed that with supply only deferred, the crisis remained a political one, not requiring action on his part. It would become a constitutional crisis either when the Opposition rejected the budget in the Senate or government funding was on the point of running out. Then he might have to take action, but not before.

But suddenly, in the first week of November, everything changed. It seemed Kerr had made up his mind that Whitlam must go.

Four days before the dismissal, Rupert Murdoch had lunch with John Menadue, his erstwhile General Manager at News Ltd and now Secretary of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. Murdoch told him that there would be an election for the House of Representatives before Christmas. He had obviously been talking to Fraser because he said that in the event the Whitlam government was defeated, Menadue would be appointed as Ambassador to Japan. (In fact, Fraser kept Menadue on for over a year as head of PM&C, after which he was indeed appointed as Australian Ambassador to Japan).

Kerr also made sure he had his ducks in a row before dismissing Whitlam. He showed High Court Justice Anthony Mason the advice from the senior law officers that the Reserve powers had fallen into desuetude and were no longer relevant. Mason disagreed, but added a rider that Whitlam should be warned before being dismissed. This would allow him the option of recommending an election and then contesting it as prime minister. Kerr ignored the rider. Against Whitlam’s advice, Kerr also consulted Sir Garfield Barwick CJ, a former political adversary of Whitlam who had found against the Labor government in every case that had come before the High Court. The Chief Justice had provided the Governor-General with a written advisory opinion that the Reserve powers existed, and Whitlam could be dismissed. Finally, Charteris gave Kerr the green light from the Palace to exercise the Reserve powers. He also reassured Kerr that rather than causing reputational damage to the Crown in Australia, dismissing Whitlam would likely do it good.

When the Prime Minister arrived at Government House on 11 November, Kerr knew his intention was to recommend a half-Senate election. If Whitlam gave Kerr this written advice, he would be bound to accept it. Instead, Kerr gave Whitlam a letter of dismissal before he could provide that advice. He later claimed he could not accept any such advice under circumstances where the government had not first obtained supply. This defies credibility. As Hocking has pointed out, “Fraser had already publicly stated on 22 October 1975 that he would respect whatever decision the Governor-General made, later conceding that if the half-Senate election had been called he would have resigned the Liberal leadership and the budget bills would have been passed.”

Without giving the Prime Minister any inkling of what he had decided, Kerr had conspired, probably for at least a week, with the Leader of the Opposition, who had arrived at Yarralumla before Whitlam and knew he was to be commissioned as caretaker prime minister. The only condition attached to his appointment was that he should recommend an election; Fraser admitted later he was not even required to secure supply. This on its own makes a nonsense of Kerr’s justification for refusing to consider a half-Senate election.

With Parliament not yet having been prorogued, the House of Representatives passed a motion of no confidence in the new prime minister, immediately followed by a vote of confidence in the Member for Werriwa (Gough Whitlam). The Speaker went to Government House bearing this advice for the Governor-General, who could quite properly have re-instated Whitlam as Prime Minister. Kerr refused to see him. At the swearing-in ceremony for new Ministers, Kerr attempted to justify this. He said he could not have re-instated Whitlam because he had already determined on a certain course of action and had to carry it through.

There was no justification in 1975, on constitutional or any other grounds, for the Governor-General to dismiss a government which retained the confidence of the House of Representatives. There was no rational reason – including the possibility of involving the Palace – for refusing to accept the Prime Minister’s recommendation for a half Senate election. There was no justification at all for such indecent haste. with neither of Kerr’s self-imposed conditions for Vice-Regal intervention having been met. Supply had not been rejected and funds were available until after Christmas.

Why was the Governor-General so determined that Whitlam had to be replaced in such a hurry?

Something else must have been going on.

https://johnmenadue.com/shame-fraser-shame-the-overthrow-of-edward-gough-whitlam/

READ FROM TOP: IT WAS A CIA JOB....

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....

"their hand".....

Spooky fiddling: The CIA playbook and the overthrow of Whitlam

By Jon Stanford

In a telephone conversation between Kissinger and Nixon following the 1973 military coup d’état in Chile, the President asked if “our hand” showed in the overthrow and death of the democratically elected President Allende. Kissinger explained that “we didn’t do it”, in terms of direct participation in the military actions. “I mean we helped them”, Kissinger continued, “[redacted words] created the conditions as great as possible.”

Source: Peter Kornbluh, The Pinochet File

As outlined in previous articles in this series, following its meeting in June 1974 on the problems caused by the Whitlam government, the US State Department had ruled out any “spooky fiddling” in Australia.

On Kissinger’s return, however, his decision to move the relationship into the US National Security Council (NSC)’s jurisdiction signalled that a more robust strategy had been adopted. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) would be involved.

In any operation in Australia, the CIA would have to operate with a very light touch. As suggested in the only ‘Top Secret’ paragraph in a record of meeting with the Defence Secretary in February 1975, Ambassador Marshall Green was clearly aware of the risks involved:

“Secretary Schlesinger expressed the opinion that U.S. installations would be allowed to remain in Australia as long as Whitlam is in charge. Green agreed, with two exceptions: (1) If Minister Cairns ever became head of the Labor Party, the U.S. would find it difficult to stay; (2) if current investigations in the U.S. became linked with Australia, the resulting storm might shorten our stay.”

The “current investigations” were clearly those being undertaken by the Senate’s Church Committee into covert actions undertaken by the CIA in other countries.

An additional constraint was that Australia was a member of Five Eyes, at that time known as the UKUSA agreement. This was a very substantial intelligence sharing agreement between Anglophone countries. The group’s protocols required that any foreign intelligence officer operating in Australia should be ‘declared’ and no covert operation should be mounted against the host government.

Nevertheless, since these protocols were largely devised by the CIA, they may have been honoured by that agency as much in the breach as in the observance.

Labor came to power in 1972 deeply suspicious of ASIO, which under Charles Spry had developed a close relationship with the CIA. They believed, justifiably, that ASIO had been used by conservative governments to spy on left wingers like Cairns and systematically undermine the party. Justice Hope, who headed a Royal Commission into the security services established by Whitlam in 1973, confirmed that ASIO was “politically biased” and “the whole system was substantially directed to the left wing of politics”.

James Angleton, the CIA’s Director of Counter-intelligence, was suspicious about the new Labor government from the very beginning. Intelligence sharing was significantly reduced following Whitlam’s letter to Nixon in December 1972. The view in the CIA was that “the Australians might as well be regarded as North Vietnamese collaborators”.

Attorney General Murphy’s March 1993 ‘raid’ on ASIO’s headquarters added fuel to the flames. Based on information passed to him by a faction of anti-Whitlam Cold War warriors in ASIO, Angleton instructed the CIA station chief in Canberra, John Walker, to ask ASIO head Peter Barbour to state publicly that Whitlam had lied to Parliament about the raid. The objective of this extraordinary intervention was to force the Prime Minister to resign. Barbour simply refused.

The Prime Minister’s attitude to the security agencies hardened as the government moved to the left after the May 1974 election. In July, Whitlam instructed Barbour to cease collaboration between ASIO and the CIA. As Blaxland wrote: “Barbour felt this would be harmful to the nation, causing damage to critical intelligence links”. He persuaded Whitlam to allow him to wind the relationship back to a lower level.

Following the NSC’s assumption of jurisdiction over the relationship with Australia after August 1974, outlined in part 2 of this series, what role would the CIA have played? In his book CIA Diary, Philip Agee, a young CIA officer who served in Ecuador and later went rogue, reveals details of the CIA playbook, some of which are relevant in the Australian context. The objective, if this playbook was followed, would have been to destabilise the government while at the same time eliminating the possibility of Cairns, the Americans’ true bête noire, becoming prime minister.

Is there evidence that this occurred? As suggested below, a CIA covert action cell may have been active in Australia at this time.

Jim Cairns was riding high when he became Treasurer in December 1974, but shortly afterwards his decline began. His relationship with his private secretary, Junie Morosi – a relationship which seemed genuine and mutual – became a magnet for the popular media and was a factor in the government’s declining popularity.

One likely avenue for dirty tricks relates to a letter Cairns supposedly sent to George Harris, a Melbourne dentist, inviting Harris to identify possible sources for a foreign loan, with a finder’s fee of 2.5 per cent. Cairns always vehemently denied signing the letter. His denial was credible. As Treasurer, he agreed with his department’s strictures regarding unconventional loan raising. He had consistently opposed paying any commission for such transactions. As Acting Prime Minister in January, he had revoked Rex Connor’s commission to seek a large overseas loan (on his return, Whitlam reinstated it).

Nevertheless, Cairns was forced to resign for misleading Parliament. The purported letter, a scratchy photocopy, was leaked to the Murdoch press. Was it genuine? What was its source?

Perhaps of most interest in exploring this question is that the CIA, in reporting Cairns’ downfall, stated in its classified National Intelligence Daily that “some of the evidence had been fabricated”.

As discussed in Part 1, Rex Connor, was also dismissed for misleading Parliament. A reporter from the Melbourne Heraldtracked down Tirath Khemlani, Connor’s intermediary, and published a front-page story contradicting Connor’s assurances that he had stopped actively seeking foreign borrowings. Connor duly resigned. Fraser then seized on this ‘reprehensible circumstance’ and announced he would block supply.

A week later, his briefcase bulging with papers and his mouth with potato crisps, Khemlani descended on Australia, seemingly intent on involving the Prime Minister in the affair. What was his motive? Dishing the dirt on a major client is not generally a career enhancing move for executives in the financial sector. Did money change hands? The journalist involved said that Khemlani “did not ask for money and nor was he paid anything”. Various unconfirmed allegations, however, include that Khemlani “was rumoured to be in the pay of the CIA”.

There is no proof of CIA intervention. And yet, Cairns’ fall from grace was complete and revelations about Connor had caused Fraser to block supply. If we pose the question of cui bono – the US NSC would be high on the list.

In September 1975, Whitlam dismissed ASIO head Peter Barbour, who was not popular with the CIA. The Cold War warriors within ASIO had compiled a dossier on Barbour’s practice of travelling in company with his “beautiful Eurasian secretary”. With outstanding chutzpah, the head of ASIO’s Canberra office, Colin Brown, who was conducting an affair with the wife of the CIA’s John Walker, told the Hope commission his boss’s travelling habit was “ill-advised and indiscreet”.

Barbour’s dismissal left a gap at the top of ASIO just when the Prime Minister could have benefited from someone who had his back. Whitlam was about to break cover in what was obviously a mission to find out the truth about CIA activities in Australia.

The Prime Minister’s inquiries to Foreign Affairs and Defence revealed that a senior CIA officer, Richard Stallings, had been operating undeclared in Australia. In 1966-70, Stallings had been in charge of establishing Pine Gap for the CIA. More recently, he had been working at a CIA base at Willunga in the Adelaide Hills, where his former deputy at Pine Gap, Victor Marchetti, told journalists he was employed by the Agency’s covert action division.

Whitlam was furious. Tange had deceived him over the purpose of Pine Gap, which, being a CIA installation, was clearly used primarily for espionage against the Soviet Union. Also, against all the diplomatic protocols for Five Eyes countries, the CIA had been running undeclared officers in Australia.

Having discovered that Stallings had rented a house from the leader of the National Country Party, Doug Anthony, Whitlam, as James Curran states, “threw caution to the wind” in a speech on 2 November. “After all the self-control he had shown in previous years on the US facilities, after all the firm assurances he had given about them to American counterparts … he finally succumbed to temptation.” Whitlam accused his political opponents of “being subsidised by the CIA”.

This statement aroused fire and fury on both sides of the Pacific. The State Department issued a denial that Stallings was employed by the CIA while its Director, Bill Colby, denied involvement in Australian politics. Yet Whitlam had discovered some of the truth about Pine Gap and was due to answer a question on notice from Anthony on its ownership and functions in Parliament on the afternoon of 11 November.

The NSC would have had two overriding concerns. The first was that Whitlam would reveal the identities of CIA officers in Australia and that the Pine Gap facility was an espionage operation run by the CIA. The second was that Whitlam would formally provide the requisite one-year notice that the agreement to host Pine Gap would not be renewed when it expired on 9 December. Marchetti said later that the threat to close the facility “caused apoplexy in the White House. Consequences were inevitable … a kind of Chile was set in motion.”

Although Kissinger stood down as National Security Adviser on 3 November, as Secretary of State he remained a senior member of NSC and would still have been directing this operation. What would he have done? Although Cairns had gone, Whitlam could no longer be relied on to safeguard Pine Gap. The best outcome was for the Labor government to go. But, to return to the opening passage about Chile, it was essential that “our hand” did not show in its demise. Whitlam was now leading in the opinion polls. The Governor-General reported to the Palace that Whitlam was exuberant in early November, convinced Fraser would back down. If he were to be dismissed and there was any hint of a Chile-like coup in Australia, Whitlam could campaign at the next election on an anti-American interference ticket and quite possibly regain office. That would be fatal for the facilities.

Following Whitlam’s speech, the American response took nearly a week to arrive. It was carefully considered. Kissinger turned to Ted Shackley, Chief of the CIA East Asia Division, who had been deeply involved in the Chile operation and whose name may well be the redacted item at the head of this piece. On 8 November, Shackley sent a demarche – a confidential agency to agency signal – to ASIO. He said he could not see how the issues raised by Whitlam could do other than “blow the lid off those installations in Australia where the persons concerned have been working and which are vital to both of our services and countries, particularly the installation at Alice Springs”. Unless the problems could be solved, he “could not see how our mutually beneficial relationships are going to continue. The CIA does not lightly adopt this attitude.”

The cable was devilishly clever. It reeks of Henry Kissinger. If it fell into Whitlam’s hands, which was not intended, it allows for the interpretation that Pine Gap was a joint facility and that only intelligence sharing was being endangered, leaving plenty of room in an election campaign for plausible deniability that ANZUS was under threat. On the other hand, its dog whistling interpretation for the cognoscenti, which amounts to an ultimatum, is far more menacing. Blaxland, in his history of ASIO, states that according to one assessment, “the Shackley cable was probably the most serious note passed to Australian authorities in the history of bilateral relations between Australia and the United States”.

Whitlam was shown the cable and was angry but undeterred. He read out to Tange his proposed reply to the Parliamentary question. The Defence Secretary, who was aghast, had obviously picked up the subliminal message in Shackley’s cable that may well have been intended for him. He told the Prime Minister’s staff that the disclosure that Pine Gap was a CIA facility for gathering top secret intelligence could mean the end of the alliance. For that reason, he believed it constituted “the gravest risk to the nation’s security there has ever been”.

Tange was clearly at the end of his tether. It seems likely from the State Department meeting in June 1974 that the Americans regarded him almost as an agent of influence. In 1977, Andrew Hay, a senior Coalition staffer who was deeply involved in investigating the loans affair, told Toohey “Tange was operating behind the scenes to see the end of the Whitlam government”. If so, he would surely have advised Malcolm Fraser, his former Minister at the time Pine Gap was established, of the signal from Fairfax, Virginia.

It is often suggested that the CIA’s ultimatum to ASIO played no part in the Governor-General’s thinking because there is no evidence that he was briefed on the American concerns. This is incorrect. John Farrands, the Chief Defence Scientist, was the senior Australian official most closely associated with Pine Gap. In 1977, on the basis he would deny the story if it ever emerged, Farrands told Brian Toohey about a call he made to Kerr on 8 November, the day the CIA’s demarchearrived. On the basis of Tange’s instructions, Farrands advised the Governor-General of the security concerns about Whitlam. The Defence Minister, Bill Morrison, who was aware of the briefing, later told a journalist, “I don’t think [the briefing] was decisive, but I think it reinforced [Kerr’s] position”.

The CIA would not have approached Kerr directly. Apart from the risks, they were not best placed to influence him. To return to the CIA playbook, as Agee records about a destabilisation campaign in Jamaica “no major political action of that nature would have been undertaken without the approval, and probably the participation, of the British. After all, special rules apply for CIA operations in Commonwealth countries …”

https://johnmenadue.com/spooky-fiddling-the-cia-playbook-and-the-overthrow-of-whitlam/

READ FROM TOP: IT WAS A CIA JOB....

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....

bull gough....

Whitlam’s biggest bull story By Elliot HannayForty-nine years ago, the Australian Prime Minister and the President of Indonesia met in a tiny sugar town in North Queensland and tried to convince the world they were discussing beef cattle exports, and not the invasion of East Timor.

They never fooled the locals who didn’t see much action on the cattle front, just a series of closed meetings with high security at low-profile locations. But the ploy kept a team from the Canberra Press Gallery chasing their collective tails for several days.

It should have been the answer to a journalist’s dream. One of those rare opportunities to “record the first rough drafts of history,” but it ended up being the biggest media farce I ever experienced.

It also remains a mystery because many of the questions raised that week have never been answered. Did Gough Whitlam sell out East Timor? Is it okay for an Australian prime minister to lie publicly if it’s in the national interest?

I’m in no position to offer definitive answers, but I can tell you what I saw and heard while covering the event in the first week of April 1975.

The plan was for Whitlam’s meeting with President Soeharto to be low key. No twenty-one-gun salute in Canberra for the visiting head of state, no dinners at Kirribilli House, no invitation to address Parliament and certainly no probing questions at national media conferences.

East Timor was in turmoil. The fiercely anti-communist Indonesians, fearing a socialist or even communist state being created on their doorstep, were poised to invade. But we were being told their President just wanted to have a cuppa and a chat with Gough in the Townsville Travelodge, before visiting a farm at Brandon about one hour’s drive south of the city to inspect a prize bull. There was also talk of a quick trip to Magnetic Island to cuddle a koala.

I went to the airport to cover the arrival for Townsville ABC News, and picked up a Sydney current affairs officer who was travelling with the group. Whitlam’s speech writer, Graham Freudenberg, also hitched a ride in our taxi.

When we reached the Travelodge, the entrance was blocked by placard waving, chanting protesters, whose main theme was “Hands off Timor.” Freudenberg suddenly became anxious, and asked if I knew who had organised the protest.

I told him I could identify several high-profile communists from the trade union movement, Fred Thompson, Col Emery, and old Bill Irving, along with stalwarts from the far left of his own party.

Freudenberg had clearly been expecting a trouble-free visit away from the big Sydney, Melbourne and Canberra protests that were supporting independence for East Timor under the leftist revolutionary party of Fretilin.

So, I told him that if the PM’s advisors had been trying to avoid encounters with the far left by coming north to so-called redneck land, they had been misinformed. History showed that North Queensland could be surprisingly politically diverse and had once elected a Communist Party member to State Parliament.

Like the protesters, the media, both the Canberra pack and we locals, were kept away from the VIPs. There were the usual well-crafted releases, but the subject matter was controlled. Oh yes, the good news from the PM’s PR people was that visuals, photos, and TV footage, would be allowed on the farm visit.

Away from their native soil in the Canberra Press Gallery, the elite of my profession seemed strangely disempowered and searched frantically for different leads and slants on farmed-out joint releases.

Of course, they were astute enough to sense Timor must have been on the hidden agenda, they just could not break through the facade that Whitlam and his minders had erected. The spin worked.

Not long after, Whitlam was dismissed by the Queen’s man in Canberra, Governor General Sir John Kerr, and five Australian journalists were killed in cold blood while covering the Indonesian invasion of East Timor. The Balibo Five.

However, more details have been revealed in recent times with the 40-year release of DFAT documents. The records confirmed the visit was all about Timor. The “Brandon bull story” had been a ruse.

Former Australian Ambassador to Indonesia, Richard Woolcott, who attended all the meetings, claimed that invasion was never discussed. Whitlam told Soeharto that maintaining good relationships with Indonesia was paramount in Australia’s national interests and his preferred option was a democratic process to integrate East Timor with Indonesia.

This might not satisfy those who wanted the Prime Minister of the day to support Timorese independence. There were also reports from former diplomats in 2020 that Woolcott’s minutes had been “sanitised” for the Australian records and that a more accurate version, supporting invasion, was provided to the Indonesians.

It is interesting to note that the records show Gough was more worried about relationships with Indonesia being damaged by the far left than from the right of Australian politics.

As Ambassador Woolcott recorded from one of the meetings, Whitlam tried to explain the complexities of his own party to President Soeharto and observed that the left, who were openly critical of Indonesia’s actions, were “patronising, paternalistic and wholly convinced of the purity and the soundness of their own views.”

It’s hard to believe such an utterance came from a Labor leader who openly referred to his Cabinet colleagues as “comrade”. No wonder politicians want to keep un-sanitised statements like that secret for 40 years.

https://johnmenadue.com/whitlams-biggest-bull-story/

READ FROM TOP

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....

gough's file....

The continual cover up – Jenny Hocking on the strange disappearance of Gough Whitlam’s ASIO file By Jenny HockingAnd it is not just Gough Whitlam’s ASIO file that has been “culled” by the National Archives of Australia. The relevant Government House Guest Books at the time of the Dismissal have disappeared and the entire archive of Kerr’s prominent supporters, including Lord Mountbatten, was accidentally burnt in the Yarralumla incinerator.

I was made sharply aware of the conceptual and physical fragility of archives as historical representation 20 years ago through a chance encounter, or more precisely a lost encounter, with Gough Whitlam’s Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) file. I had stumbled onto Whitlam’s security file quite unexpectedly through a reference to it in another, unrelated, file. Clearly, any file maintained by the domestic security service on Gough Whitlam would be a critically important historical record in itself, and even more so given the Whitlam government’s fractious relationship with the security services and the well-known surveillance excesses of ASIO and the state Special Branches at that time.

To find evidence of the existence of an ASIO file on Whitlam that I had never expected was a rare moment of archival anticipation. That anticipation was dashed four months later when the Archives informed me that, having maintained this security file for nearly 40 years, it had been destroyed in a routine culling, just weeks before I requested it. Although Archives assured me that, according to ASIO’s records, the now destroyed file “contained material of a vetting nature only”, this is now impossible to verify. A request for access to the ASIO documents referred to in this response and on which this claim about the nature of the file was based, went unanswered.

As a former Prime Minister, Whitlam was a recognised “Commonwealth Person” (https://www.naa.gov.au/help-your-research/getting-started/commonwealth-record-series-crs-system), for the purposes of the Archives management systems. These are “individuals who have had a close association with the Commonwealth” and whose records are therefore expressly collected and preserved for history. Notwithstanding that acknowledged significance, the Archives had issued an authorisation for ASIO to destroy Whitlam’s security file within weeks of my request to view it. It brings to mind Blouin’s arch observation that “a historian working in state archives, particularly on topics related to the recent past, is constantly engaged in some way in a struggle with the politics of state-protected knowledge”.

The misplaced destruction of Whitlam’s security file compounds the unsettled history of the dismissal by allowing the circulation of competing speculations over its coincident erasure: was this a vetting file as ASIO stated, did the file identify agents or surveillance methods, would its release have led to files on other members of the Whitlam government? This latter is no idle speculation. ASIO was already monitoring deputy Prime Minister Dr Jim Cairns, whose ASIO “dossier” was sensationally leaked to The Bulletin in 1974, causing immense damage to the Whitlam government and to Cairns personally. The possibility of security files on other ministers and even on Whitlam himself is only stirred by the deliberate destruction of ASIO’s vetting file. In the absence of the file itself an already clouded history becomes further compromised.

It was this episode that introduced me to the force of what Elkins terms “archival scepticism” in archive-based research. Whatever the reason for its apparent destruction, the Archives had successfully removed Whitlam’s ASIO file from public view and therefore from the consideration of history. In doing so it had played an important role in the construction of the dismissal in history, in which a security file on Gough Whitlam does not and cannot now feature. This underscores precisely, if there were any doubt about this, that archives are not neutral replicators of documented history, but politicised re-creators of it.

The Lost Archive: Government House Guest Books

In 2010, I first requested access to the Government House guest books held by the Archives, which provide the details of visits and visitors to “their Excellencies” at Yarralumla. The catalogue lists a total of twenty-nine files, enumerated consecutively, constituting visitor books from May 1953 to February 1996. The guest books appear regularly from July 1961 until July 1974, before stopping altogether until December 1982.

The Archives insisted that the guest books for this period had never been transferred from Government House and they now appeared lost since neither institution claimed to hold them. What is puzzling in this regard is that Archives’ enumeration system, which numbers each file consecutively, has two consecutive numbers assigned yet not included in the catalogue corresponding to the missing dates, suggesting two missing files given identification numbers by the Archives which are no longer listed. The only other gap in these books, for a much shorter period between 1960 and 1961, has no such missing consecutive numbers in the catalogue which might accommodate a lost file.

In June 2023, the Archives submitted a “s40 access application” to Government House requesting the delivery of the Government House guest books for 1974–75. Government House replied that “it does not hold any guest books, visitor books, guest registers or visitor registers from 1975 as defined by the Archives Act 1983”. It should be noted that Government House is required under the Act to place the guest books as Commonwealth records in the Archives, which it had done for the previous decade and which it was the responsibility of the official secretary to deliver. The guest books for 1975 are now officially lost.

These missing guest books add fuel to the longstanding speculation that security and defence officials, notably the Chief Defence Scientist Dr John Farrands as the recognised authority on Pine Gap and the Joint Facilities, had briefed Kerr in the week before the dismissal about mounting security and defence concerns over Whitlam’s exposure of CIA agents working at Pine Gap, and his planned Prime Ministerial statement on this in the House of Representatives on the afternoon of 11 November 1975. This claim, driven largely by journalist Brian Toohey, that Farrands provided a briefing for Kerr was emphatically denied by Farrands and the Head of Defence, Sir Arthur Tange. Farrands threatened to sue Toohey and The National Times, although the Vice-regal Notices show that he had met Kerr on 28 October 1975, not the week before the dismissal.

The Burnt Archive: Sir John Kerr’s Prominent Supporters

In 1978, soon after Kerr left office, a cache of letters “of outstanding value” to Kerr was accidentally reduced to ashes in the Yarralumla incinerator. The usually punctilious official secretary, David Smith, wrote to Kerr expressing his dismay at having so carelessly left this box of significant letters unattended in the photocopying room, from where an errant cleaner, according to Smith, had inadvertently thrown the entire contents into the incinerator.

Kerr had sought these congratulatory letters for use in his forthcoming autobiography Matters for Judgement. Among his correspondents was the Queen’s second cousin, Lord Louis Mountbatten, Prince Philip’s uncle and King Charles III’s great mentor; the former Governor-General and distant royal relation, Viscount De L’Isle; and other prominent individuals supporting Kerr’s dismissal of Whitlam. These names alone indicate that these burnt letters were as important to history as they were to Kerr. Were it not for this secondary file of correspondence between Smith and Kerr detailing the saga of the “burnt letters”, the existence and apparent inflammatory end of Kerr’s correspondence with his minor aristocratic supporters would never have come to light. The letters themselves now never will.

Philip Ziegler’s authorised biography of Mountbatten, however, gives just a glimpse of this story. Ziegler recounts that Mountbatten wrote to Kerr days after the dismissal, congratulating him on his “courageous and correct action” in dismissing Whitlam. It was a remarkably partisan royal intercession, and Mountbatten was not alone among Kerr’s royal supporters. We now know, thanks to letters released in 2020 following the High Court’s decision in my legal action, that King Charles also fully supported Kerr’s actions. Charles’s letter to Kerr, written in starkly similar terms to Mountbatten’s weeks after the dismissal, leaves no doubt of Charles’s support for Kerr; “What you did […] was right and the courageous thing to do”.

As Kerr later wrote to the South Australian lieutenant-governor, Sir Walter Crocker, “I never had any doubt as to what the Palace’s attitude was on this important point”.