Search

Recent comments

- god's murders....

2 hours 16 min ago - the cliff.....

2 hours 31 min ago - qui bono?

3 hours 45 min ago - envious....

6 hours 6 min ago - crimea...

8 hours 13 min ago - bombing liberation....

8 hours 58 min ago - refrain....

10 hours 24 min ago - trust?....

11 hours 27 min ago - int'l law....

11 hours 52 min ago - more bombs....

21 hours 41 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

the dirt of clean energy...

Mining the Planet to Death

The Dirty Truth About Clean Technologies

The poor South is being exploited so that the rich North can transition to environmental sustainability. Entire swaths of land are being destroyed to secure the resources needed to produce wind turbines and solar cells. Are there alternatives?

By Jens Glüsing, Simon Hage, Alexander Jung, Nils Klawitter und Stefan Schultz

There’s a dirty secret hidden in every wind turbine. They may convert moving air cleanly and efficiently into electricity, but few know much about what they are made of. Much of the material inside wind turbines are the product of brutal encroachments on our natural world.

Each unit requires cement, sand, steel, zinc and aluminum. And tons of copper: for the generator, for the gearbox, for the transformer station and for the endless strands of cable. Around 67 tons of copper can be found in a medium-sized offshore turbine. To extract this amount of copper, miners have to move almost 50,000 tons of earth and rock, around five times the weight of the Eiffel Tower. The ore is shredded, ground, watered and leached. The bottom line: a lot of nature destroyed for a little bit of green power.

A visit to the Los Pelambres mine in northern Chile provides a clear grasp of the dimensions involved. It is home to one of the world’s largest copper deposits, a giant gray crater at an altitude of 3,600 meters (11,800 feet). The earth here is full of metalliferous ore. Just under 2 percent of the world’s copper production comes from this single pit.

Dump trucks, 3,500-horsepower strong, transport multi-ton loads down the terrace roads that line the mine. The boulders are transported by conveyor belt almost 13 kilometers (8 miles) into the valley, where the copper is extracted from the rock. This processing requires huge amounts of electricity and water, a particularly precious commodity in this arid region.

The project is operated by Antofagasta, a London-based Chilean mining corporation that owns 60 percent of the mine. The company built a hydroelectric plant in 2013, almost exclusively to supply electricity to Los Pelambres. Farmers protested against it, and have blamed the project for water shortages in the region.

Now, though, the mine is slated to grow even larger. The company is pumping additional volumes of desalinated seawater from the Pacific coast across the country. Company executives hope this will enable them to continue operating the mine for a few more years. Global demand for copper, after all, is expected to grow immensely, for power cables and electric motors. And for wind turbines.

There are great hopes that the green technology can be used to help save the climate, but that rescue also entails stripping the planet of precious resources. And this is the paradox behind what is currently the most important project of the industrialized world: the global energy transition. The dilemma, which is becoming increasingly apparent, is also on the minds of the 25,000 or so delegates at the World Climate Conference currently taking place in Glasgow. Deposits in the poor South are being exploited so that the rich North can transition to environmental sustainability. At least to a lifestyle that appears sustainable. Mathis Wackernagel, a resource researcher who lives in California, describes it as a disastrous development. "We haven’t quite thought the future through,” he says.

Wackernagel, who was born in Basel, Switzerland, in 1962, is one of the most influential figures in the environmental movement. He coined two metaphors that have influenced thinking about sustainability around the world.

One is the idea of the environmental footprint, which indicates how much land and sea area is needed to renew the resources that we have consumed. According to Wackernagel’s calculations, 1.75 Earths would be needed for the planet to regenerate itself. If all the people on the planet were to behave as wastefully as the inhabitants of Germany, it would require almost three Earths.

The other is Earth Overshoot Day, which marks the day each year on which humanity has used as many resources as the planet can replenish in a year. This year, that day fell on July 29. The two metaphors serve to underscore Wackernagel’s main point: "We are using resources of the future to pay for the present.”

He’s referring to the daily consumption of around 90 million barrels of crude oil, the use of land for buildings, roads or arable land – and also the exploitation of mineral resources. Wackernagel says the biological budget is limited and that humans must decide what they want to use it for. If we use it to mine copper, then it won’t, for example, be available for the cultivation of beets. He says it’s too short-sighted to think that all we have to do to protect the environment is to recreate the fossil-fueled world with electricity and swap the six-cylinder Jaguar for the battery-powered Tesla.

Few are aware of this fact as they drive their electric vehicle, use electricity from wind or solar power, or have a lithium-ion storage facility set up in the basement – making them feel like pioneers in sustainability. Many don't realize how extremely polluting the production of raw materials from which climate technologies are manufactured really is. Who knew, for example, that 77 tons of carbon dioxide are emitted during the manufacture of one ton of neodymium, a rare earth metal that is used in wind turbines? By comparison: Even the production of a ton of steel only emits around 1.9 tons of CO2.

Almost 50 years after American scientist Donella Meadows and her fellow campaigners warned of "the limits to growth” in their report to the Club of Rome, the overexploitation of nature is taking on a surprising new dimension. The massive demand for materials has continually been the underappreciated factor in all the technologies that are intended to help make the world more sustainable. Wind turbines, photovoltaic systems, electric cars, lithium-ion batteries, high-voltage power lines and fuel cells all have one thing in common: Inconceivable amounts of raw materials are consumed in their production.

In a solar park measuring 1,000 by 1,000 meters, there are fully 11 tons of silver. A single Tesla Model S contains as much lithium as around 10,000 mobile phones. An electric car requires six times as many critical raw materials as a combustion engine – mainly copper, graphite, cobalt and nickel for the battery system. An onshore wind turbine contains around nine times as many of these substances as a gas-fired power plant of comparable capacity.

It is the specific properties they contain that makes these metals so desirable. Cobalt and nickel increase the energy density in a battery. Neodymium amplifies the magnetic forces in wind generators. Platinum accelerates processes in fuel cells, and iridium does the same for electrolyzers. Copper’s conductivity makes it relevant in every electrical installation. Around 150 million tons of copper are installed in power lines around the globe. And humankind is only at the beginning of its energy transition.

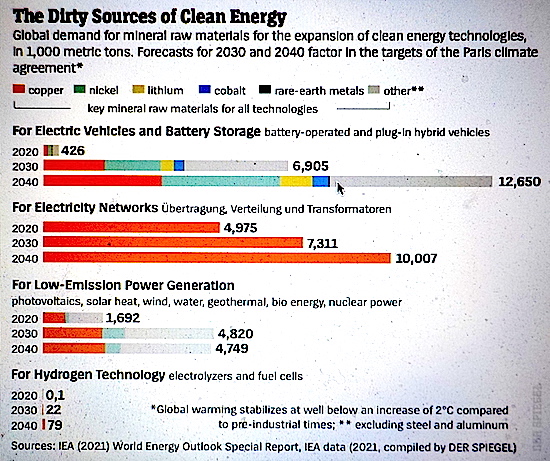

According to calculations by the International Energy Agency (IEA), global demand for critical raw materials will quadruple by 2040 – in the case of lithium, demand is expected to be as high as 42 times greater. According to IEA head Fatih Birol, these materials are becoming "essential components of a future clean global energy system.”

Over the course of his professional career, Birol, who has a doctorate in energy economics, has never really had to deal with these materials until recently. His area of focus had always been oil and gas, first as an analyst for OPEC and later, at the IEA, founded in Paris in 1974 by the consuming countries in response to the first oil price crisis. The crisis painfully demonstrated to governments just how dependent they had become on the drip of a few producing states.

Almost a half a century later, Birol is now observing how the industrialized nations are falling into a new dependency – not on oil, but on metals. And it could prove to be even more serious.

Many of these critical commodities come from a small group of countries. Indonesia and the Philippines command around 45 percent of the global nickel supply. China supplies 60 percent of rare earth metals. The Congo is responsible for about two-thirds of cobalt production. South Africa dominates around 70 percent of the platinum market.

The geographical concentration is even more pronounced than in the oil business. OPEC covers just 35 percent of global supply. In mining, on the other hand, only 10 countries produce around 70 percent of the raw materials by value.

The good news is that, from a geological view, there is no shortage of metals. Even the rare earths are neither rare nor earths. Nor are they in any way exclusive to China.

On the other hand, mining is becoming more and more expensive, and ore quality and raw material content are declining. As the tight supply meets surging demand, prices are skyrocketing. Within 12 months, important metals have become massively more expensive: The price of nickel has risen by 26 percent, copper by 43 percent and aluminum by 56 percent. The price of lithium carbonate has roughly tripled in a year to more than $20,000 per ton. At the same time, stocks of metal in warehouses around the world are plummeting.

It’s obvious that something is out of balance. IAE head Birol is familiar with the situation from the oil business, and the metals markets could also fall into a similar situation. Birol speaks of the looming discrepancy between ambition and supply: between the aspiration to protect the climate and the difficulty of obtaining enough affordable copper, nickel and lithium.

Given that the depletion of resources is concentrated in a few countries, particularly those that are politically unstable, their supply is becoming a global security issue. "This could lead to disruptions,” warns Birol.

And it begs the question: How clean are green technologies really?

Mining: Rich Soils, Poor People

Hamdallaye was a village in northwestern Guinea in West Africa, a settlement of thatched mud huts and shady fruit trees. Sociologist Mamadou Malick Bah, 25, used to live in the village. But Bah had to leave last year. The village and its 700 inhabitants stood in the way of bauxite extraction.

The reddish ore that lies hidden beneath the earth is considered Guinea’s gold, since it is the raw material for aluminum, an important light metal in wind turbines and power lines. The inhabitants of Hamdallaye were resettled in a new village located five kilometers away from the old one. In photos, the new community, built on a spoil heap, resembles a desert landscape.

"It’s like being on Mars,” says Bah. Not much can grow there. Indeed, the soil is so poor that CBG, the partly state-owned Guinean mining company, now has to support the small farmers, who previously made a living off their own plots. Each farmer is provided with the equivalent of 94 euros a month. "More and more young people are leaving the village," says Bah, and the locals weren't given jobs at CBG anyway.

Companies began mining the Boké region more than 50 years ago, and today the excavators run almost nonstop. Guinea, one of the world’s poorest countries, has the largest bauxite deposits on Earth. Mining concessions have been awarded for a large part of the country’s territory, and Chinese companies are also involved.

The environmental consequences have been devastating. Bah says it has resulted in the destruction of natural diversity and sources of drinking water. The machines’ vibration caused his hut in the old village to collapse four years ago. But he still hasn’t received any compensation.

One controversial aspect of the mining project is the fact that the German government is involved. In 2016, Berlin provided loan guarantees to the tune of 246 million euros for the expansion of the mine, despite criticism from the German Environment Agency. In a report, the German Economics Ministry praised that globalization in Guinea could be managed equitably. Rather than focus on the expropriations of West African farmers, the report instead noted that the investment helped guarantee jobs back in Germany.

The report noted that the expansion of the mine would enable the Germany-based company Aluminium Oxid Stade (AOS) to secure its production for more than 10 years. AOS is the last remaining German bauxite processor and an important supplier of products for the automotive industry. An Audi E-Tron vehicle includes 804 kilograms of aluminum.

The controversial bauxite mining in West Africa is but one example of the disconnect between popular environmentally friendly products "Made in Germany” and the origins of their ingredients. Indeed, it is the paradox of abundance that plagues countries like Guinea. They have enormous mineral resources and yet they fail to attain widespread prosperity.

But this isn’t necessarily a given. Norway is also blessed with resources, but it also manages to put that advantage to good use: The country is reliable politically, its institutions are strong, and it has a low crime rate. Good governance is the key to ensuring that countries like Guinea can also profit from the global commodities boom.

The major deposits can be found in the three "A’s” – Africa, Australia and the Andes, all of which are suffering extremely from climate change. In all these places, water is extremely scarce, and enormous amounts of energy are needed to process the ore.

The crushing and grinding of rock accounts for up to 3 percent of global electricity demand. That’s more than the entire amount consumed by Germany.

The mining industry even describes itself as being a "dirty, dusty, dangerous” business. No other industry is as destructive to the environment. The operations often leave behind a lunar landscape, in addition to basins full of contaminated sludge, so-called tailings, in which the residues of the processing are collected. Around 32,000 of these toxic lakes are located around the world. In January 2019, a dam located near an iron ore mine in Brazil burst and created a mudslide that poured into the valley and killed more than 270 people.

In the past, ignoring the environment was something that mining companies could afford to do. But they face resistance today. The weekend before last, a protest by indigenous Mayans in Guatemala against a Swiss mining company extracting nickel in the northeast led the country to declare a state of emergency. Many customers of mining companies, especially investors, are no longer giving an easy pass to misconduct – at least not within the biggest companies. They avoid industries that are considered environmentally dubious, even if they are financially promising.

This is forcing the mining companies to act, too. "We meet all the requirements to be interesting for investors,” Iván Arriagada, the CEO of Chilean copper giant Antofagasta has said, courting investors. Arriagada, 58, is a modern executive with a master’s degree from the London School of Economics – and not one of the old-school mining tycoons who would never show up without wearing a tie. Arriagada is seeking to position Antofagasta as a pioneer in environmental protection – at least to the extent possible in the industry.

He says that close to half the water the company uses in mines like Los Pelambres now comes from the sea instead of the mountains; and by 2025, that figure is expected to rise to 90 percent. "We use every drop of water seven or eight times before it evaporates,” Arriagada says. He also says that the electricity needed is to be generated entirely from renewable sources in the coming year.

Around a dozen companies are involved in the global commodities business. Switzerland’s Glencore dominates the cobalt market, the U.S. company Albermarle is No. 1 in lithium, Brazil’s Vale is the global leader in nickel, and Chile’s Codelco and Britain’s Antofagasta are leaders in copper. All these companies are feeling growing pressure to protect the environment. "We really need to change our mindset,” Rio Tinto CEO Jakob Stausholm confessed at a recent investor conference in London. The Anglo-Australian company has set the goal of halving its CO2 emissions by 2030. At the same time, the conditions under which the mining industry can extract mineral resources are growing more difficult.

Over the past 15 years, the copper ore content in Chile’s mines has fallen by almost a third to 0.7 percent. Three generations ago, that figure was 2 to 3 percent. Today, the industry has to dig much deeper to extract the same quantities of precious metals than it did in the past – and it consumes correspondingly more electricity and fuel.

The deposits that are easiest to extract have already been mined, and no major new deposits have been exploited in Chile in years. Only 2 percent of all explorations actually result in the construction of a mine. "It takes luck, a lot of perseverance and persistence,” says Antofagasta CEO Arrigiada. And on average, it takes 16 years from the discovery of a suitable spot before mining operations begin. "Our planning horizon spans decades,” he says.

Indeed, it is difficult to increase the current supply of metals. According to IEA forecasts, volumes from active and planned mines won’t be enough to fill demand. For example, current mining operations will cover only half of future demand for lithium and cobalt. "Supply and investment plans for many critical minerals fall well short of what is needed to support rapid deployment of solar panels, wind turbines and electric vehicles," warns IEA chief Birol.

Arriagada says his company anticipated the uptick in demand in its forecasts, but says that the momentum surprised them. The main reason for this is the rapidly growing demand for green technologies. He says that electromobility is currently responsible for 1 or 2 percent of copper demand. By 2030, that share is expected to rise to more than 10 percent.

"The pandemic has created an awareness that we need to act collectively and quickly to address systemic risks like climate change," says Arriagada. His company is profiting from that development.

Electric Cars: Treasures in the Chassis

Depending on the battery type, an electric car requires between 150 and 250 kilograms of special raw materials. The largest part is comprised of graphite, nickel and copper, with the rest composed of manganese, lithium and cobalt. Carmakers are now pushing ahead with the expansion of their e-fleets, and competition has broken out among them over securing supplies of raw materials.

This spring, BMW CEO Oliver Zipse made a bold pledge to his customers and shareholders. He proclaimed that BMW would build the world’s "greenest” car. It’s not only the air in the cities that should become clean, but also all the links in the value chain. For Zipse, this also means that raw materials can’t come from mines where children work, or waters are contaminated by pollutants. With cobalt, one of the most important ingredients in modern electric batteries, that often happens.

Zipse’s words may have a whiff of cheap environmental PR, but he's likely being genuine. After all, he’s simply following economic logic. Electric cars are all about outperforming internal combustion engines on sustainability. Otherwise, the most important sales argument falls flat.

Even if the production of the raw materials for an e-car and its battery devours extreme masses of resources, it is still far more environmentally advantageous than driving a conventional vehicle. In terms of its carbon footprint, the electric car has a clear advantage.

According to the IEA, an internal combustion vehicle emits 40 tons of greenhouse gases over a life cycle of 200,000 kilometers, more than twice as much as an electric car, despite the CO2-intensive production of the battery.

The weakness of the e-car is that it requires so many more mineral raw materials than internal combustion vehicles, including quite a few critical materials that are often mined under dubious conditions. The battery in the iX electric SUV recently unveiled by BMW contains about 6 kilograms of cobalt, 10 kilograms of lithium and 60 kilos of copper. These are all raw materials that are seldom or almost never found in a gas or diesel engine.

Around half of the growth in demand that green technologies will trigger over the next two decades is related solely to the foreseeable boom in electric cars and energy storage. BMW is forecasting that, by 2030, 50 percent of the cars it sells will be purely electric vehicles, up from a share of only 3 percent today.

The company finds itself in a dilemma. Mine workers in Congo shouldn’t have to foot the bill for affluent people in Munich to have clean air. "We can’t limit ourselves to just operating sustainably in our own factories,” says Patrick Hudde, head of supply chain sustainability and raw materials management at BMW. That has prompted the automaker to take an unusual step.

The company says it no longer wants to rely on intermediaries and their pledges that their raw materials come from clean sources. BMW is now buying lithium and cobalt directly from mine operators - not in Congo, where most of the mining is done by hand, but from mining companies in Morocco, Australia and Argentina, which BMW claims it has carefully examined.

Hudde says the selection process was rigorous, and that more than 100 suppliers didn't receive contracts "because we weren’t convinced of their compliance with environmental and social standards.”

But BMW reaches its limits quickly when it comes to its ability to conduct controls. The company plans regular and at times unannounced visits by trained auditors. Employees at suppliers are also able to issue complaints directly to BMW. "If we become aware of violations, we promptly ensure that the grievances are remedied on site,” he says. Ultimately, though, they are only spot checks. BMW relies on its partners to comply with contractually agreed social and environmental standards. In the event of a violation, the carmaker can ill afford to drop a supplier. It would be next to impossible to quickly replace a major cobalt supplier.

Faced with such a predicament, a company could try to reduce its use of raw materials by technological means. The first generation of Toyota’s Mirai hydrogen car still required 40 grams of platinum per vehicle. In new models, the amount required has dropped by a third; and by 2040, Toyota wants to reduce it to 5 grams. But even engineering feats like that at best only alleviate the industry’s dependence on raw materials. It cannot be eliminated.

China: More Powerful than OPEC

That reality has a direct impact on relations between Western economies and China. With a share of around 50 percent of global demand for raw materials, China now occupies a position of supremacy that was reserved for the United States in the middle of the 20th century, says, Peter Buchholz, the head of the German Mineral Resources Agency (DERA). "That’s not going to change anytime soon,” he says.

China is the largest supplier of numerous metals. At the same time, Beijing has built up a network of partner countries – and it has made them dependent. It pumps capital into countries like Chile, Bolivia and Congo, buying mining rights and access to scarce resources.

China’s dominance in processing is even more pronounced. The country is the leading producer of 23 out of 26 refined products, and its share of rare earths is around 90 percent. Beijing aims to cover all stages of the value chain, from ore to e-car batteries. China controls about 75 percent of all lithium-ion battery production capacity worldwide.

America and Europe have watched with concern as the commodity giant’s market power grows. Thierry Breton, the European Union’s internal market commissioner, warns of "total dependence on China,” especially for supplies of rare earths. Ten years ago, China demonstrated the leverage it has when it suddenly cut exports of rare earths, leading prices to skyrocket and plunging the world into a supply crisis. It provided the occasion for Germany to formulate a first draft of its raw materials strategy.

China is using its investments in Africa and South America specifically for a geopolitical power play. It self-confidently secures influence, grants loans worth billions and thus creating ties of dependency with an increasing number of countries. According to Hamburg-based economist Thomas Straubhaar, nothing about the moves being made by Beijing is by chance. The country pursues a "sober strategy of power,” he says. Access to raw materials has become an instrument of foreign policy.

China’s unique position isn’t due to the fact that the soils in the Far East are richer in minerals – there are sufficient deposits of raw materials all over the world. In terms of geology, Germany could even cover some of its metal requirements itself.

Regions like the Harz and Erzgebirge mountains already have centuries-old mining traditions. But businesses have instead chosen to purchase metal from abroad – at the price of dependence. Ultimately, it is cheaper to obtain supplies from overseas. The main thing is that they don’t have to get their own hands dirty.

Elsewhere, importing countries have sought to counter China’s superiority by reactivating disused deposits. In California, investors restarted the old Mountain Pass mine in 2018 to extract rare earth metals. And in Sweden, iron ore mining company LKAB is planning to extract rare materials from the waste generated from its exploration activities. Other companies are exploring the planet’s last frontiers: the treasures that lie dormant in the deep sea, billions of tons of metalliferous minerals.

Companies like Deep Green and UK Seabed Resources are exploring ways they can commercially exploit the seabed. There have also been advances in conveying technologies. Harvesters weighing up to 250 tons are to transport the raw materials upward using an armored hose. They need to be highly reliable and able to withstand extreme water pressure. It would be too much trouble to have to keep bringing them back up to the surface for repairs.

Analysts at BCC Research are expecting a new commodity rush, triggered by deep-sea mining, with market volume of up to $15 billion by the end of the decade. At the same time, environmentalists are warning of the destruction of ecosystems that have barely even been explored if the seabed is plowed through by the square kilometer.

The deep sea can’t be relied upon as a quick, competitive and, more importantly, environmentally friendly, source of raw materials. Recovering metals from waste provides greater promise.

Recycling: Shredding for New Resources

The island of Peute in the Port of Hamburg is home to Europe’s largest copper works, operated by Aurubis. The plant has been producing copper for pipes, sheet metal and wire since 1907, more than a million tons of copper products each year. In addition to the ore delivered from Chile, Peru or Brazil, the factory relies heavily on recycled materials.

Mountains of the commodity can be found at the facility, heaps of shiny, reddish copper granulate of varying consistencies, some coarse, others fine – all of it produced from discarded wire. Next to the mounds are barrels filled with the shredded remains of computers or mobile phones. Christian Plitzko, a metallurgist at Aurubis, grabs a handful. "This is where the treasures are that we’re interested in,” he says.

"If producers would label their circuit boards, we would later, in the recycling process, be able to specifically remove certain metals before they are melted down."

Aurubis metallurgist Christian Plitzko

Plitzko, who has been with Aurubis for 24 years, looks down at the shiny green and silver material in his gloved hand. "This used to be a circuit board in a computer,” he says. Every kilogram of circuit board material contains 250 grams of pure copper.

It is technically feasible to extract other metals from such waste, but the effort remains too great. If it were possible to specifically remove, for example, parts made of neodymium from a circuit board with the help of a barcode and a laser, then it might be worth it, says Plitzko. "If producers would label their circuit boards, we would later, in the recycling process, be able to specifically remove certain metals before they are melted down.”

Demand for copper has noticeably increased, and the smelting furnaces at Aurubis are working at full capacity – with production at the factory continuing around the clock, seven days a week. The company benefits from the fact that copper is an important element in all green technologies and that recycling is a relatively clean method of compensating for the scarcity of the raw material. Recovering the metal that is built into a circuit board takes just a 20th of the energy required to extract the metal via mining.

The process enables the industry to cover at least part of its demand for raw materials using methods that do not increase its dependence on source countries. More than ever before, recycling has become a key element of commodities supply. But there is plenty of potential that isn’t yet being tapped. More and more electronic waste is being produced – in the form of discarded mobile phones, televisions and refrigerators. But instead of ending up at recycling stations, a lot of valuable raw materials find their way into landfills or waste incinerators. In Germany, only about 44 percent of electronic scrap is collected, while the global rate is lower than a fifth.

The wind power industry has a particularly significant role to play. Many turbines from the industry’s early days are now ready to be replaced. Most of the materials used in the towers and turbine housings can be reused, but its not quite as easy with the rotor blades, since they are frequently made with epoxied carbon fiber or fiberglass. Many end up in the incinerator.

The producers of electric cars are eager to avoid repeating that mistake. They are working on concepts that will make it easier to recycle the valuable materials that are currently being used to manufacture new vehicles. Half of the aluminum that BMW uses in its engines and auto bodies, for example, is recycled, but the share is significantly lower for materials like nickel, cobalt and lithium that are used to produce batteries.

The electric vehicle era, after all, has only just begun, and there isn’t yet a huge supply of used batteries available. That, though, will change as soon as e-cars make up half or more of all vehicle traffic in the coming years. By then, BMW plans to have introduced a recycling strategy that leads to lower and lower reliance on primary raw materials.

Electric car pioneer Tesla even hopes that it will one day be able to cover almost all of its raw materials needs with old batteries. Jeffrey Brian (JB) Straubel, who has been the company’s technical mastermind for years, alongside Elon Musk, even founded his own recycling company for the purpose. He believes there will be a "radical shift” to lower battery prices when huge numbers of batteries can be 95-98 percent recycled.

He believes that would be both an ecological and financial breakthrough for automobile manufacturers. Batteries currently account for roughly a third of the purchase price for an electronic vehicle, mostly the result of the expensive materials involved in their manufacture.

A Volkswagen pilot facility has already begun operations in Salzgitter, right next to the site where a factory will begin operations in 2024, churning out an expected 500,000 batteries for electric cars each year. The discarded batteries are disassembled in a corrugated metal warehouse and shredded before the valuable substances inside are then filtered out.

In the long term, the company hopes to recycle 97 percent of all raw materials used. Currently, VW achieves a quota of around 50 percent, a number that is expected to soon climb to 72 percent with the help of the new recycling facility. VW does not consider old batteries to be "hazardous waste” but "a valuable source of raw materials.”

Still, recycling alone won’t be sufficient to cover the vast raw-material requirements in green industries. Rates of 45 to 50 percent for copper suggest that there is still some potential for recycling and that the eco-balance of battery systems, wind turbines and solar parks will improve. However, this calculation does not add up, says Aurubis expert Plitzko. The copper recycled today was produced and used on average 35 years ago, when significantly less of it was produced. As such, the rate is more like 80 percent, says Plitzko.

"As a society, we won’t be able to cover our entire demand for copper with recycling,” he says. "We will also need primary copper if we want to cover current and future demand.”

That means that even the most ambitious recycling efforts won’t be enough to put an end to the ruthless exploitation of our environment. Nature will continue to be depleted, in part because humanity hopes to live, work and travel in a more environmentally friendly manner in the future. For as long as we continue to maintain our current levels of prosperity, we will unavoidably continue to consume more resources, which is ultimately damaging to the biosphere. If we continue to use more than nature produces, we will exceed our planet’s limits. It’s like a bank account, says sustainability expert Wackernagel: You can overdraw your balance for a time, but not forever.

Does that mean that renouncing consumption is the only solution to reducing our hunger for raw materials, as some have proposed? Wackernagel grimaces. "That sounds to me like far too much individual suffering and sacrifice,” he says. A good life, he continues, is also possible within the ecological limits that exist. You don’t need a two-ton electric vehicle to transport a person who weighs 75 kilograms. An electric bicycle can do the job just as well, he says.

Furthermore, Wackernagel believes, a different factor will be decisive when it comes to our society’s future sustainability: the number of people. When he was born in 1962, there were around 3.1 billion people on the planet. Today, there are 7.8 billion. If the global reproduction rate doesn’t change significantly, there will be close to 10 billion by the end of the century. Wackernagel believes that the global population needs to begin dropping again. Fewer people, after all, require fewer resources. "In the longer term,” he says, "that is the most important factor.”

Read more:

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW√√√√√√√√√ΩΩΩΩΩ≈≈≈!!!

- By Gus Leonisky at 6 Nov 2021 - 12:42pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

destroying the place...

By ANTHONY HAM

How the government is failing on the environment by hiding critical science

Every year, Australia’s threatened species commissioner invites people to send in photos of cakes depicting their favourite threatened Australian animal. The “Threatened Species Bake Off” produces some remarkably lifelike cassowaries and koalas, wombats and stingrays. It is at once a classic sugar-coating of a serious issue and a lighthearted attempt to raise awareness

.This year there were more than 700 entries. Among them was a cake of a dead greater glider alongside a fallen log and a sign that said “Logging is criminal”. Clearly it wasn’t quite what the commissioner intended. One minute the photo was on the commissioner’s Facebook, the next it was gone. There was no explanation and Acting Commissioner Dr Fiona Fraser wasn’t commenting. When people started asking questions on social media, the entry quickly returned to Facebook.

If the government was trying to keep the image from public view, it failed spectacularly. The dead-glider cake took out the People’s Choice Award for 2021.

Even cakes, it seems, can be dangerous to a government desperate to avoid bad publicity.

Secrecy often lies at the heart of the Morrison government’s public messaging. It’s not only a well-documented personal predilection of the prime minister’s, dating back to his invention of “on-water matters” as immigration minister, and beyond, including around his family travels to Hawaii and Cornwall, and for Father’s Day this year. His government deploys similar secrecy when formulating public policy of great importance to the nation, ranging from its attempts to keep secret the deliberations of national cabinet through to its routine abuse of freedom-of-information laws and most recently its blindsiding of close ally France in the lead-up to the AUKUS pact announcement.

This obsession with secrecy, and with the suppression of potential bad news stories, is especially pronounced when it comes to science and the environment.

In 2019, Professor Don Driscoll of Melbourne’s Deakin University and immediate past president of the Ecological Society of Australia, surveyed 220 Australian ecologists, conservation scientists, conservation policymakers and environmental consultants. The results, published this year in the international science journal Conservation Letters, found that one-third of government employees who responded had experienced “undue interference” when it came to public communications about their research.

Fifty-two per cent of government respondents had been prevented from publicly sharing scientific information. Of these, 82 per cent had been constrained by senior managers and 63 per cent by a minister’s office. For those respondents who had communicated scientific information in the public domain, 42 per cent reported being harassed or criticised for doing so. Just over half of respondents (56 per cent) believed that the suppression of scientific communications had worsened over recent years.

Some of the quotes to emerge from the study were deeply disturbing:

I was directly intimidated by phone and Twitter by [a senior federal public servant].

Not being able to speak out meant that no one in the process was willing or able to advocate for conservation or make the public aware of the problem.

It feels terrible to know the truth about impacts to the environment, but know you’ll never get that truth to the public and that the government doesn’t care at all. They want us to give them politically supportive information, not science.

I feel resentment when I am expected to “toe the line” and support decisions I consider wrong and not in the best interest of the environment and not based on sound scientific data.

I felt I was effectively lying by not revealing a major environmental threat, as if complicit in a crime.

The forms of suppression reported included “complete prohibition on communication, as well as alteration of communications to paint government or industry actions or decisions in a misleading, more environmentally friendly, light”.

Speaking to the media can be problematic for all public servants. Watching over their shoulders at the federal level, the Australian Public Service Code of Conduct warns that: “An APS employee must not disclose information which the APS employee obtains or generates in connection with the APS employee’s employment if it is reasonably foreseeable that the disclosure could be prejudicial to the effective working of government, including the formulation or implementation of policies or programs.”

Social media guidelines – drafted in 2011 and tightened significantly in 2017 – further discourage a whole range of behaviours, from signing online petitions to making “personal comments about the character or ability of other people, including members of the parliament”. Federal public servants can’t even “like” social media posts without exposing themselves to sanction.

In a unanimous ruling in Comcare v Banerji in 2019, the High Court held that the federal government did not breach the Constitution’s implied freedom of political communication when it dismissed a public servant who, in her own time, posted anonymous yet scathing criticisms of the government. The court accepted that posts critical of an employee’s department were likely to do “damage to the good reputation of the Australian Public Service”.

It remains unclear whether less vitriolic criticism might be permissible. Even so, it would take a brave public servant to test such nuances in court.

“The whole messaging within the system is about control of the story,” Professor Driscoll tells me. “If people break those rules they can be disciplined. They see the pressure for that coming most often from senior management, and senior management are very often political appointments … People are aware of the work environment they are in and know that they will be disciplined by their superiors. Or in some cases, they’re afraid of what their peers will say to them, because often their peers have bought into the idea that the public service is about pleasing the minister rather than performing a public service.”

It doesn’t have to be like this. In 2018, the Canadian government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau implemented the Model Policy on Scientific Integrity. A key objective of the policy was to “[f]oster a culture that supports and promotes scientific integrity in the design, conduct, management, review and communication of research, science, and related activities”.

One provision declares that “No [departmental] employee shall suppress, alter or otherwise impede the timely release of research or scientific information in the absence of clear and compelling reasons for doing so.” Another requires that any government department “recognizes the right to freedom of expression by researchers and scientists on matters of research or science”, and, in fact, the policy actively encourages them “to speak about or otherwise express themselves on science and their research without approval or pre-approval”.

In Australia, with neither such protections nor a culture that recognises the value of independent scientific research in public debate, one in five of respondents in Driscoll’s study suffered job insecurity, damage to their career or job loss, or had left their field as a result of speaking out.

In the absence of informed and objective scientific participation, said one respondent, fake news often fills the evidence void: “I could see that social and media debate was exploiting the lack of information to perpetuate incorrect … interpretations … to further their own agendas.”

“What I find so devastating about the suppression,” says Euan Ritchie, professor in wildlife ecology and conservation at Deakin University, “is that at the very time that we need really good information for making decisions about the environment, and ideally doing much better, many are actively suppressed from doing so. The bigger picture is that it’s an affront to democracy. Supposedly when we go to the voting booth, we vote based on what we know and what we’ve been told. If information is actively being held back and kept away from us, then we can’t – as the voting public – make informed choices. That’s not a democracy.”

When asked why he felt able to speak out, Driscoll was adamant: “I’m not afraid. If I have less success in getting external funding because I criticised the government, so be it. It’s time that all scientists came out from the shadow of being afraid for their funding and shared with the public the truth of what they’re finding.”

The consequences of scientific suppression go beyond individual researchers and questions of democracy.

Since European colonisation in 1788, at least 34 Australian mammal species, or one-tenth of Australia’s endemic mammals, have been driven to extinction. That’s the worst record of any country over the past two centuries. And the outlook for many vulnerable species remains perilous.

Launched in 2015, Australia’s Threatened Species Strategy, now overseen by Threatened Species Commissioner Sally Box and Environment Minister Sussan Ley, is the government’s response to this appalling record. Part of the strategy was to fund the Threatened Species Recovery Hub, which the government said would bring together “Australia’s leading conservation scientists to help develop better management and policy for conserving Australia’s threatened species”.

The Threatened Species Strategy’s Year Five Progress Report, released in June this year, found very few successes to celebrate. Of the 70 priority species, for example, only 24 “significantly improved” in their population recovery. Even this was misleading: nearly a third of these simply had populations declining at a slower rate than they had in the previous decade.

Leaving aside the substance of the report, there was something more sinister afoot.

On June 26, 2019, Professor Brendan Wintle, director of the Threatened Species Recovery Hub, wrote to the then Department of the Environment and Energy to notify it that a scientific paper, of which he was the lead author, had been accepted for publication in Conservation Letters. Titled “Spending to save: What will it cost to halt Australia’s extinction crisis?”, the paper compared Australia’s spending on threatened species to spending by the United States government. The paper found that Australia’s annual budget for threatened species recovery was “around one tenth of that spent by the U.S. endangered species recovery program, and about 15% of what is needed to avoid extinctions and recover threatened species”. The article also argued that: “The past decade has seen a rapid decline in expenditure on environmental management in Australia, with cuts of 37% to environmental investments in the Australian Government budget since 2013.”

The government was not happy.

On June 28, Beth Brunoro, a departmental first assistant secretary, asked in an internal email for meetings to be set up with Wintle, and spoke of “a fundamental difference of perspectives on the role of the hub”.

Four days later, the department’s Dr Nicholas Post, an assistant secretary, wrote to, among others, Sally Box, that: “Beth and I are meeting with Brendan Wintle later this week to remind him of the importance of focusing on science rather than policy matters.” A week later, after departmental officials had met with Wintle, Post wrote again to the commissioner about plans to “commence detailed revision of the proposed research paper”.

In late August, after a meeting between Wintle, Box and senior departmental officials, a departmental memo laid out three possible scenarios:

“Option 1: The authors publish the paper without hub affiliation, after consulting the Department on their calculations of Australian Government spending on Threatened Species.

Option 2: They don’t publish the paper.

Option 3: They publish the paper with a different set of authors, individuals who do not represent the Hub leadership and/or knowledge brokering team.”

The memo acknowledged that “it is not really within our remit to instruct them not to publish it or to drastically change the authorship, but we may mutually arrive at this point through a discussion of how best to achieve their objectives”.

In the end, the authors agreed to remove any branding of the Threatened Species Recovery Hub from the paper, and it was published in November 2019 to very little public fanfare.

Speaking nearly two years later, Wintle remains bemused by the whole experience: “I was surprised that the publication of a paper that provides a scientific basis for estimating the funding we would actually need to recover our threatened species caused so much anxiety for the public service.”

Many in the scientific community were appalled. Don Driscoll called it a “disgraceful example of scientific suppression”. Professor Martine Maron, another of the paper’s co-authors, expressed similar dismay, telling Guardian Australia, “We expect our governments to welcome robust, peer-reviewed science, regardless of what it reveals.”

Wintle is keen to point out that he has had different experiences elsewhere. “Not all governments are the same,” he says. “I currently find working with the Victorian state government to be very different to working with the Commonwealth. They are much more open to constructive criticism … Unlike the Commonwealth, the current state government doesn’t view scientists providing policy critique as crossing the line.”

With Threatened Species Commissioner Sally Box on extended leave, Acting Commissioner Fiona Fraser was also unavailable for comment for this article. The department’s media team instead referred me to the department’s statement from May 14, 2021: “We strongly reject any assertion that department officials sought to pressure researchers in relation to the non-publication or authorship of the paper.”

What happened after the paper was published was even more concerning.

The funding that supported the Threatened Species Recovery Hub ran for five years, ending in mid 2021. In the department’s new 10-year round of funding for the Threatened Species Strategy, Wintle, his co-authors and the hub lost out – the hub was closed.

“The net result,” Wintle says, “will be a significant reduction in focus on threatened species. That is a politically good outcome for the current Commonwealth government because their performance on threatened species is pitiful.”

Funding for threatened species will now be more diffuse, spread across a number of other hubs, none of which is focused primarily on threatened species. Euan Ritchie says that “there are many people who think that the federal government went with another research group in part because they didn’t like the fact that members of the first group told them things they didn’t want to hear, nor make public. If you look at the group that Brendan had composed, it was pretty much a who’s who of ecology and conservation in Australia. And the group Brendan led were extraordinarily productive, in terms of new research insights and on-ground work. With all of this in mind, it did seem an odd decision.”

Wintle admits that he had always understood “the prospect that the future of that hub depended on how comfortable the government felt with my commentary … It did definitely place constraints on what I felt I could say and when.” And he cannot escape the conclusion that speaking out on the government’s performance on biodiversity, threatened species and climate change ultimately came with consequences.

“I wake many nights,” Wintle says, “wondering if we might still have a national threatened species recovery research hub if I hadn’t published on the current government’s underspend on threatened species, and hadn’t conveyed the depth of our policy failure to stem the extinction crisis on [the ABC’s] Four Corners.”

For a government obsessed with controlling the message and avoiding embarrassment, the Great Barrier Reef has presented an even greater challenge.

In June this year, UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee announced a draft decision to add the Great Barrier Reef to its List of World Heritage in Danger. The government was outraged. Environment Minister Sussan Ley claimed that Australia had been “blindsided” and denied due process by UNESCO. Prime Minister Scott Morrison described the process as “appalling”.

It was a difficult argument for Australia to make on its merits. After all, UNESCO had based its decision in large part on Australian government data and scientific reports on the state of the reef. At no point did the government claim that the Great Barrier Reef wasn’t in danger – because it couldn’t.

The federal government has a statutory requirement to publish an “Outlook Report for the Great Barrier Reef” every five years. Prepared by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA), the report bases its findings on an exhaustive array of data on everything from the health of the reef’s coral and its other marine populations to water quality.

In 2014, the report described the reef’s outlook as “poor”. In 2016 and 2017, the reef experienced major bleaching events, which occur when ocean temperatures rise and stressed coral expels its symbiotic algae, turning it white and making it highly vulnerable to mass die-offs. The GBRMPA’s next Outlook Report, in 2019, downgraded the reef’s prognosis from “poor” to “very poor”.

Another mass bleaching event occurred in 2020. Later the same year, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) completed its own World Heritage Outlook report, in which it described the conservation outlook for the Great Barrier Reef as “critical”. In the 40 years since it was inscribed on the World Heritage List, the Great Barrier Reef has lost half of its coral cover.

Against this backdrop of scientific data and devastating projections, the recommendation by the IUCN to UNESCO that the Great Barrier Reef be added to the in-danger list was not at all unexpected. If the Australian government had been blindsided, as it claimed, it can only have been because it wasn’t paying attention.

Traditionally, adding a World Heritage site to UNESCO’s in-danger list was neither political nor controversial. In 2010, for example, the US government asked UNESCO for Florida’s Everglades to be returned to the list. America’s largest subtropical wilderness was imperilled and they wanted the world to know what was required to save it.

Nor is such a designation meant to be punitive. “That’s not its purpose,” says Professor Terry Hughes, Australia’s leading reef scientist at the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies. “Its purpose is to first highlight that a particular property is in trouble. And it triggers a process whereby the state party has to come up with a pathway forward in order to get the property off the in-danger list as soon as possible.”

The Australian government instead took the draft decision as an affront.

On June 23, just a few days after UNESCO announced its recommendation to the World Heritage Committee, Megan Anderson, Australia’s permanent delegate to UNESCO, wrote to the agency’s director-general, Audrey Azoulay. Her letter reminded UNESCO of “the need for intergovernmental and international institutions to continue to apply due process in interactions with their States Parties”. She also reiterated all recommendations of this kind “should be based on transparent, extensive and close consultation processes with the States Parties concerned”.

Despite the diplomatic language, it was a warning shot.

On July 12, Sussan Ley flew to UNESCO headquarters in Paris and began an eight-day diplomatic offensive, meeting with ambassadors and officials from 18 countries on her whirlwind tour. Even as Australia called for transparency by UNESCO, the minister’s delegation worked behind the scenes to secure the support of World Heritage Committee members to have the reef kept off the in-danger list.

“There wasn’t any accountability or transparency over what she was doing, or what she was saying,” says Imogen Zethoven, an adviser to the Australian Marine Conservation Society. “Her trip was all about deal-making with these countries to ensure the reef wasn’t listed on the in-danger list at this meeting. We don’t know what those deals were. We don’t know what went on behind closed doors. And we paid for it.”

Back in Australia, the government launched a charm offensive to go along with its diplomatic one, taking 13 foreign ambassadors snorkelling on the Great Barrier Reef. At the same time, in Canberra, it was scrambling to find some good news about the reef’s health. On the day that the minister arrived in Europe, chief executive of the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) Paul Hardisty received a call from a public servant who asked him to fast-track the AIMS long-term monitoring program report. In an email to senior AIMS staff at 8pm that night, Hardisty wrote: “government wants LTMP report released this week. It is not ideal but we must comply.”

The government was clearly confident that the report would contain at least some data it could use to support its case to UNESCO. If so, by demanding that AIMS supply its report early, the government was using an independent statutory authority – whose responsibility is to provide non-political scientific advice – to serve its own political ends. (Through a spokesperson, the minister rejects this criticism: “The information in the report was complete and all results verified. It was entirely appropriate, therefore, for the government to request its publication.”)

As the government likely knew, 2021 was a relatively good year for the Great Barrier Reef. Unlike in 2020, there was no bleaching event and there were signs that coral cover had improved in places. Although the long-term outlook for the reef remained of great concern, the 2021 AIMS report noted the temporary improvements in some areas, and it was exactly what the government wanted to hear.

“The report announced an uptick in coral cover in the most recent survey,” Professor Hughes says. “Since 2020 we’ve had a year of La Niña, a year of cooler conditions, so depending on whether a reef last bleached in 2016, 2017 or 2020, they’ve had a window for some recovery. The report was misrepresented to give the impression that the Great Barrier Reef has magically recovered. That’s not what the report says, but you’d have to actually read the report and dig into the facts to see what’s really going on.”

There was, it must be said, no suggestion of any impropriety on the part of AIMS. According to Hughes, “you have to read the numbers and the detail to get the nuances, which, to their credit, the AIMS scientists wrote about. They would have been under intense pressure to gild the lily. And they resisted that.”

As Hardisty wrote in The Australian in July, “the longer-term picture is not so positive … The evidence is clear and unequivocal … Mass bleaching, unheard of before the 1990s, is now becoming a regular occurrence, with major events in 1998, 2002, 2010, 2016, 2017 and 2020. We now know coral reefs take about a decade to recover after serious damage.”

According to Hughes: “The bottom line is that the corals that are coming back are the ones that are the most susceptible to bleaching and crown-of-thorns and cyclones … It’s actually setting up the reef for an even bigger fall in the inevitable next bleaching event … For every stable trajectory, or upward trajectory, there’s half a dozen more that are down. And when they’re up, they’re temporary. You get windows of regrowth, followed by the next disaster.”

That’s not the story the government told UNESCO.

On July 14, two days after the government leaned on Hardisty to release the AIMS report ahead of schedule, emails between public servants and AIMS staff discussed a “targeted pre-release” (also referred to in the emails as a “leak” or a “drop”) to two News Corp newspapers. In the days that followed, The Australian dutifully published an article titled “Coral repair raises hopes for reef as heritage vote looms”. “Historic signs of Great Barrier Reef regrowth,” read the headline in The Courier-Mail.

Not content with leaking to sympathetic media outlets, the government released a carefully edited three-page summary of the report to the other members of the World Heritage Committee. “I trust you will find this report valuable,” wrote Ambassador Anderson in an accompanying email, “including its findings of widespread recovery of coral at key sites across the property.”

“The governments of Russia, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, all saw the AIMS data before we, the Australian people did,” says Zethoven. “It’s outrageous.”

There are numerous theories as to why the government has gone to such lengths to prevent UNESCO from adding the Great Barrier Reef to the in-danger list.

Publicly at least, the government claims that it is to protect UNESCO processes. “Australia’s concerns have always been about ensuring a fair and transparent World Heritage process for the reef and the people who work tirelessly to protect it,” according to a spokesperson for the minister.

One reason for the government’s opposition to UNESCO’s recommendation may be economic: prior to the pandemic, reef tourism employed nearly 65,000 people and brought in $6 billion annually. Even so, a 2016 assessment published in The Conversation found that the Everglades, the coral reefs of Belize and the Galapagos Islands saw no discernible fall in tourist arrivals after appearing on the in-danger list.

The government also perhaps fears the damage such an adverse listing could have on Australia’s international reputation. “They’re afraid of falling from grace, the ignominy, as they see it,” says Zethoven. “They see themselves as the best reef managers in the world. They beat their drum everywhere they go internationally, so for them to have the GBR on the in-danger list is an international embarrassment, the harshest of all possible judgements.”

Australia’s standing has, in fact, suffered thanks to the government’s double standards. In 2017, when Australia took up its four-year seat on the World Heritage Committee, Stephen Oxley, Australia’s then head of delegation to the committee, made a speech berating other countries for eroding the authority of UNESCO and its advisory bodies, for how members of the committee were voting in blocs to overturn draft decisions, and for placing national interests ahead of international responsibilities. “During our term on the committee,” he promised, “Australia will be an advocate for upholding the technical integrity of the committee. We will place great weight on the analysis and advice of the advisory bodies.” Among those advisory bodies are UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre and the IUCN, both of which recommended placing the Great Barrier Reef on the in-danger list.

The Monthly has seen internal IUCN data that shows “an increasing trend to overturn and weaken Advisory body technical recommendations”. In 2005, according to the document, more than 70 per cent of advisory body recommendations were approved by UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee. In 2021, the figure was around 4 per cent. Sources within the United Nations told The Monthly that there is widespread anger at Australia’s role in this dramatic turnaround.

Australia has history in this regard, too. In 1999, the Howard government mounted a campaign to prevent Kakadu National Park appearing on the in-danger list thanks to the proposed Jabiluka uranium mine. Australia won that battle but alienated many. “It left a really bad taste in a lot of people’s mouths,” says Dr Jon Day, one of the former directors at GBRMPA and a one-time delegate to the World Heritage Committee.

Twenty-two years later, it is a similar story. “The way Australia has conducted themselves,” Day says, “they’ve really shot themselves in the foot without realising the implications of what they’ve done by upsetting other countries.”

“I don’t think Australians fully recognise how much we are now considered such a poor performer on the environment and climate,” says Zethoven. “I think there was a profound shift during the summer bushfires in late 2019, early 2020. Based on conversations I’ve had, there was such a global shock and an incredulity that a country so severely vulnerable to climate change would be so unwilling to act.”

In 2017, UNESCO released its landmark study, “Impacts of Climate Change on World Heritage Coral Reefs: A First Global Scientific Assessment”. The report carried stark warnings about the effect of regular severe bleaching, and that these precious regions, including the Great Barrier Reef, “will cease to host functioning coral reef ecosystems by the end of the century unless CO2 emissions are reduced”. It went on to argue that “drastic reductions in CO2 emissions are essential – and the only real solution – to giving coral reefs on the World Heritage List a chance to survive climate change”.

At the 44th session of the World Heritage Committee this year, the committee endorsed a draft policy that recognises climate change as a major threat to many World Heritage–listed properties and allows for the effects of climate change to be a factor when considering whether to add a World Heritage–listed site to the in-danger list. UNESCO also reiterated “the importance of States Parties undertaking the most ambitious implementation of the Paris Agreement”.

It was perhaps this shift in UNESCO policy that frightened the Australian government more than anything else. As an in-danger listing requires the government with stewardship of a World Heritage–listed site to take measures to address the site’s decline, the fact that climate change is understood to be the overwhelming threat to the reef would present a problem for a government hostile to climate action.

“That means, of course, that they have to deal with climate change,” says Zethoven. “They would have to act on the issue of climate change consistent with a 1.5-degree pathway … So they were hell-bent on trying to avoid an in-danger listing because they knew what it meant.”

The Australian government claims to have been unfairly treated by UNESCO. According to a spokesperson for the minister, “The draft climate change policy, for which Australia has been a strong advocate, recognises that climate change is a factor affecting many World Heritage properties, and almost all reefs, which is why singling out one property on the basis of global climate change is a concern.”

Such an argument rings hollow when you consider that Australia now ranks third in the world for the export of fossil fuels. Only Saudi Arabia and Russia export more. Australia’s “scope 3” carbon emissions – which include the emissions produced elsewhere by its exports – range from 5 to 9 per cent of the world’s total, and Australia has the highest per capita emissions of any country with World Heritage coral reefs.

Even so, the government’s lobbying resonated with Australia’s supporters on the committee, among them oil-rich Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Nigeria and Russia. Terry Hughes cites another reason these nations might have been persuaded by Australia’s entreaties: “if they can do this to Australia, they can do it to you”.

In an upbeat diplomatic email in July, Ambassador Anderson expressed confidence that the lobbying had worked and that Australia had enough support to block UNESCO’s recommendation. The whole process, she wrote, would “send a good message about consensus and that the committee would not need to spend a lot of time discussing [the reef]”.

And so it proved. Just as it had with Kakadu in 1999, Australia won the 2021 battle to keep the Great Barrier Reef off the in-danger list.

It was a temporary reprieve.

The new UNESCO policy document on climate change will become binding upon ratification by the general assembly in November. The Australian government must report back to UNESCO on the reef’s outlook by February 1, 2022. Even with a government commitment to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 at the Glasgow Climate Change Conference, it’s difficult to imagine UNESCO letting Australia off the hook again. A commitment to net-zero would appear to be a bare minimum if the government is to avoid an in-danger listing.

“Having documented in exquisite detail the ongoing decline of the Great Barrier Reef and the causes thereof, it’s hard to see how they could spin it,” argues Hughes. “I’m sure it’s going to be promoted heavily in the next few months that the clever scientists can fix the reef. The general public loves the concept of clever people rescuing ecosystems. But I can’t see the next report saying anything except the outlook is very poor … and nor can I see the site visit coming to any other conclusion than the reef doesn’t look anything like it did in 1981.”

After receiving Australia’s report, UNESCO will reconsider its in-danger recommendation at the World Heritage Committee’s 45th session, to be held in Russia in June 2022. When that happens, Australia will no longer hold a seat on the World Heritage Committee. Nor will it be able to claim with a straight face that it was denied procedural fairness, or that it was blindsided. There can be no more excuses.

Whatever happens, the reef will remain in danger, whether the government says so or not.

All across the environment minister’s portfolio, the obsession with secrecy, the attempts at suppression and the costly battles to silence the messenger (such as the legal fees spent trying to appeal a High Court ruling over a government’s duty of care, and the millions spent on Minister Ley’s mission to Europe to convince UNESCO to reverse its Barrier Reef decision) are a precursor to actual abdications of environmental responsibility.

With no Threatened Species Recovery Hub to advocate for threatened species in the public sphere, in September this year the government abandoned recovery plans for around 200 endangered habitats and species. Recovery plans (which set out the research and management actions necessary to stop the decline of listed threatened species) will be replaced by conservation advices, which carry more limited legal force. Recovery plans for a further 500 threatened species are also in doubt. According to Martine Maron, Australia has cleared more than 7 million hectares of threatened species habitat over the past 20 years. Brendan Wintle says, “It takes a brave government to fund research that might reveal and communicate something uncomfortable. The current federal government is neither brave nor committed to threatened species conservation.”

Also in the past couple of months, Minister Ley, who makes a mockery of the notion that the environment department is there to advocate on behalf of the natural world and our sustainable place within it, has approved at least three new coalmining -projects: the Mangoola mine in the Upper Hunter region of New South Wales, the Wollongong Coal expansion and Whitehaven Coal’s Vickery mine extension near Gunnedah in northern NSW. The latter came after a Federal Court challenge to the mine by eight teenagers who sought an injunction to prevent the mine from going ahead. Although the court refused to grant the injunction, it found that the minister owed a duty of care to protect young people from the harm caused by climate change.

The government has launched what it called a “gas-fired recovery”, which includes “unlocking key gas basins”, including the controversial Beetaloo Basin in the Northern Territory. In October, on the eve of the Glasgow Climate Change Conference, WWF-Australia released a report in which it criticised the government for paying lip-service to global diversity targets at a time when 1500 of Australia’s unique ecosystems are entirely unprotected. And a major study published this year in the peer-reviewed journal Global Change Biology found that at least 19 ecosystems spanning from the Great Barrier Reef to Antarctica were “collapsing”. It was, the report found, an issue “pivotal for the future of life on Earth”.

Collapsing and unprotected ecosystems, massive underspending on threatened species in peril, new coalmines and coal-fired power stations, a gas-fired recovery, and a government that has appealed against the very idea that it owes a duty of care to future generations – little wonder that the government wants to tell a different story.

ANTHONY HAM

Anthony Ham writes about wildlife, conservation and current affairs for magazines and newspapers around the world.

Read more:

https://www.themonthly.com.au/issue/2021/november/1635685200/anthony-ham/spin-and-secrecy-threatening-australian-environment

See also:

https://yourdemocracy.net/drupal/node/39294

https://yourdemocracy.net/drupal/node/41158

what future?FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW√√√√√√√√√ΩΩΩΩΩ≈≈≈!!!

tyres...

The booming global tire market is worth billions - but this comes at a high price, both to humans and the environment. Over 50 million car tires are sold each year in Germany alone. But where does the natural rubber for them come from?

The biggest producer of natural rubber for tires is Thailand. More than four million tonnes of rubber are harvested annually in plantations there. And demand for rubber is ever growing - because ever more tires are needed. But the labor conditions in Southeast Asia are harsh - with working days of up to 12 hours and very low wages. In addition, toxic herbicides banned in Europe are used to fight weeds on the plantations. After the harvest, the ‘white gold’ rubber is sold to brokers, who, in turn, sell it on. German tire manufacturers, like Continental, for example, are keen to stress that they use "natural commodities conscientiously.” But many car drivers don’t give a second thought about where the rubber in their tires comes from - and why we don’t recycle used tires more effectively.

Read more: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-fusUxEPwsw

Note: The two main synthetic rubber polymers used in tire manufacturing are butadiene rubber and styrene butadiene rubber. These rubber polymers are used in combination with natural rubber.

Read from top.