Search

Recent comments

- religious war....

7 hours 32 min ago - underdogs....

7 hours 43 min ago - decentralised....

8 hours 6 min ago - economy 101....

18 hours 3 min ago - peace....

18 hours 51 min ago - making sense....

21 hours 30 min ago - balls....

21 hours 33 min ago - university semites....

22 hours 21 min ago - by the balls....

22 hours 35 min ago - furphy....

1 day 3 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

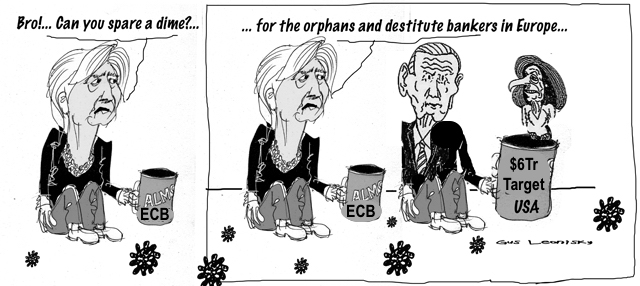

en garde, lagarde....

ECB

ECB

DER SPIEGEL: Mr. Marsh, Christine Lagarde became president of the European Central Bank on Nov. 1, 2019. How would you rate her first two years in office?

David Marsh: I would give her a medium grade. On the one hand, she has pacified the most important body, the long-divided ECB Governing Council. On the other hand, under her direction – mainly because of the COVID-19 crisis, for which she naturally bears no responsibility – the ECB's dependence on euro-area governments has increased. She doesn’t have any deep fundamental principles when it comes to monetary policy.

DER SPIEGEL: What do you mean by that?

Marsh: She says that she is neither a hawk, i.e. a monetary policy hardliner, nor a dove. Someone like her, who can live with an ultra-loose monetary policy for a long time and who also reflects the overriding, somewhat dovish character of the council, may be appropriate for the current situation. But it’s an open question whether this will be just as useful for the remaining six years of her mandate.

DER SPIEGEL: First things first: How did she pacify the Governing Council?

Marsh: Her predecessor, Mario Draghi, was a thoroughbred economist and central banker. He was convinced that he was right and was hardly interested in what his colleagues on the Council thought. His economic arguments bore the intellectual rigor of his doctoral studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and of his Jesuit upbringing. Lagarde follows a different, more mollifying approach. From the beginning she tried to accommodate hawks like Dutch central bank president Klaas Knot and Bundesbank chief Jens Weidmann, to demonstrate that she took them seriously. She is a lawyer and can get along with other people, deploying empathy, charm and humor.

DER SPIEGEL: Lagarde has a reputation for being a good communicator. Has this impression been confirmed?

Marsh: Internally, definitely yes. The hawks believe the climate has greatly improved. They know that Lagarde understands less about the technical side of monetary policy than they do, but also that she has other talents.

DER SPIEGEL: Such as?

Marsh: Her persuasiveness, her many years of experience as managing director of the International Monetary Fund, her contacts in politics, especially with French President Emmanuel Macron. But also, the connections she has established in the U.S., Germany and Italy.

DER SPIEGEL: The mood may be better, but Weidmann has nevertheless announced that he is resigning at the end of the year. He seems frustrated by his lack of power on the Council. That makes it seem as though things haven’t actually changed much under Lagarde’s leadership.

Marsh: That's right. Weidmann did his best to convince the other Council members of the validity of his conservative monetary approach. But in the end – given his permanent status as leader of the Council’s orthodox minority – the results have been rather meager. In addition, because of his ordo-liberalistic principles, he has fallen out with Europe's most powerful politicians – Macron and Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi.

DER SPIEGEL: His resignation, then, can be seen as his way of escaping the corner into which he has painted himself?

Marsh: It seems so. After all, despite his young age of 53, after 10-and-a-half years in the job, he is the third longest-serving president of the Bundesbank, after Karl Blessing and Karl Otto Pöhl. On the other hand, he has now unnecessarily brought the office of Bundesbank president into the ongoing negotiations over Germany’s next governing coalition. The issue will be tied up with unseemly political skirmishing that has precious little to do with monetary policy.

DER SPIEGEL: Weidmann's predecessor, Axel Weber, also gave up in 2011 out of irritation over ECB policy. Does that not demonstrate that the Germans, or at least elements of the country’s political class, have never really come to terms with eurozone membership?

Marsh: I would put it in a more nuanced way: The Germans have had to face up the fact that they are not alone in the world. Thirty years ago, I wrote: "The Bundesbank is much too powerful to be controlled by others. But it has too much power to rule alone.” In 1999, Germany would not have accepted an immediate takeover of the Bundesbank by the ECB – which, at that time, did not have its current significance. Instead, we have seen a slow transformation, a gradual de-Bundesbankisation of the German central bank. Weidmann's departure is the latest step in a long journey. Germany’s leaders should have prepared the electorate for the final destination on this voyage. Angela Merkel did not want to – or could not – do this and has left it to Olaf Scholz. Perhaps that is Jens Weidmann's farewell gift to the new chancellor.

DER SPIEGEL: Olaf Scholz, the Social Democrat who is likely to move into the Chancellery once coalition negotiations are complete, will have a significant say in who gets the job. What kind of successor should the federal government appoint? Another hawk, to mollify the German public? Or a dove who won't resign in frustration after a few years?

Marsh: The successor will have to be a new type of president. If Isabel Schnabel, professionally qualified as she is, switched from the ECB to the Bundesbank, it would be a setback for Claudia Buch, who in return would have to transfer to the ECB to maintain gender balance, a rather inefficient changeover. I would prefer a tandem solution, as has already been successfully practiced at the Bundesbank over the years.

DER SPIEGEL: What might that look like?

Marsh: The rather apolitical Claudia Buch would take over the presidency for two years until the end of her eight-year mandate. Marcel Fratzscher – the former ECB official who has close ties to the Social Democrats, is president of the Germany Institute for Economic Research, and is a man of great renown well beyond Germany’s borders – would become vice president for two years, with a strong international focus, and then would take the presidency. But the longer the procedure goes on, the more political it will become.

DER SPIEGEL: Why?

Marsh: Because there is a risk that the appointment will be decided only at the end of long and complicated coalition talks. Even in more normal times, without the current coalition battles, such processes are often accompanied by disagreement, setbacks and surprises. The last time an SPD chancellor chose the head of the Bundesbank was in 2004, when Ernst Welteke had to leave. There were three initial candidates, Peter Bofinger, Ingrid Matthäus-Maier and Hans Reich – before then-Chancellor Gerhard Schröder and his finance minister, Hans Eichel, could agree on the fourth, Axel Weber.

DER SPIEGEL: Back to Lagarde. Right from the start, she declared she would communicate more transparently with the general public and provide simple, jargon-free explanation of the ECB's monetary policy. Is such a thing even possible?

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW √√√√√√√√√√√√!!!

- By Gus Leonisky at 3 Nov 2021 - 12:08pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

debt as a weapon...

Kevin Barrett: Welcome to Truth Jihad Radio, the radio show that wages the all-out struggle for truth by uncovering all sorts of interesting facts and perspectives that are normally banned, covered up, obscured, spun or otherwise messed with in the corporate controlled mainstream. Today we’re going to the rather complex subject of international economics, but by way of an analysis of empire. John Perkins and Confessions of an Economic Hit Man showed us the debt dimension of empire. Our US empire is the first empire ever that runs on debt more than anything else. And if you want to learn how that works, the place to go is Super Imperialism by Michael Hudson. It’s been recently reissued with a new concluding chapter, and it pretty much breaks it down: It’s a fantastic book, and kind of disturbing, too, that makes you realize how shaky the foundations of our whole world right now are. So let’s talk about it. Hey, welcome Michael Hudson, how are you?

Michael Hudson: Well, I’m pretty good, and it’s good to be here.

Kevin Barrett: Good to finally have you. I’ve been reading your stuff for years, and I just read Super Imperialism actually for the first time, I hate to admit, and it’s quite a masterpiece. I would think anyone teaching a university course on these matters would have to assign it. But I’m not sure that it’s mainstream acceptable enough to get that assignment. What’s been the response?

Michael Hudson: To this book? The problem is not acceptability. The problem is getting it into the curriculum. I was a professor of economics since the 1960s, and there’s no way to fit either international finance or even money and credit, or the balance of payments, into the curriculum . I don’t think the balance of payments, which is the key to the world’s debt problem today, is taught anywhere. I was told that in 1969 and 70, my course was the only course in balance of payments accounting in the United States. Most economists actually look at economies as if they’re done on barter. And money doesn’t really appear because economists say, “Well, we owe the debt to ourselves, so it doesn’t really matter.” But the “we” who owe the debt or the 99 percent, and the “ourselves” or the one percent that things are owed to in America and internationally (are not the same). Right now, you’re seeing crises erupt throughout the world. Argentina, again, is about to default or repudiate the debt that it owes to the International Monetary Fund that essentially serves as an arm of American foreign policy. And that’s what I discuss in Super Imperialism: how the International Monetary Fund lends money to support governments that are friendly to the United States.

Michael Hudson: And when the U.S. policy, neoliberalism usually, gets these economies in trouble, the IMF will lend money to a country like Argentina to support flight capital. It will enable all of the U.S. corporations in Argentina, and the rich families, to move their their domestic money in pesos or escudo, or whatever they’re dealing with, out of the country into dollars. And then the IMF lets the currency collapse—and in fact, insists that the currency collapses. Because it says when if you can’t pay your debt, the way to repay it is to impose austerity and lower your wages and stop investing in public infrastructure, stop government spending. And so the result of this policy of the IMF with the World Bank right behind it, is to make countries less and less able to pay their debts. And so they fall deeper and deeper into debt and more and more dependent on U.S. official credit. IMF credit and essentially debt is used internationally to impoverish other countries, just as it’s now impoverishing the U.S. economy.

Kevin Barrett: And this all raises the question of why you were the only one teaching this in the universities, given its central importance for history, geopolitics, and the way things really work in the world. And that’s where I wonder whether there must not be some kind of political resistance in the form of a kind of a propagandistic way of pushing particular views of politics and economics coming down from the top. Before I read John Perkins’ book years and years ago, I had no idea that that was actually how it worked. It seems like somebody must not want us to know that this is how it works.

Michael Hudson: Not really. Certainly, the government wants to know how it works. The reason that I taught balance of payments was I’d been working for many years for Chase Manhattan as their balance of payments analyst, and then for Arthur Andersen, the accounting firm that was later closed down for fraud, as its balance of payments analyst. And the topic just wasn’t taught in economics. The economic theory in the universities pretty much ignores money and credit. That’s what Steve Keen and myself and the MMT people at University of Missouri at Kansas City, who have now all been dispersed—Stephanie Kelton, Randy Ray—we’re all trying to say, “wait a minute, you’re looking at the economy as if it’s purely technological, purely physical, and you look at technology and GDP growth, but actually, what grows most rapidly is debt, and the debt is what is slowing the economy down and preventing the economy from growing. There’s an attempt not to look at money and credit created by banks or what they’re creating it for, which is essentially for real estate, for economic rent.

Way back in the 1890s, economics stopped. There was an anti-classical reaction against Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, Marx, Henry George, all the people who were talking about economic rent. Most of the fortunes in America were made by economic rent. So the wealthy fortune gatherers and rent extractors promoted a kind of barter theory of the economy. But in terms of what the government wanted, when my Super Imperialism came out, I had thought that probably a lot of left wingers would buy the book. And indeed it was quickly translated into Spanish and Russian and other languages. But immediately, Herman Kahn at the Hudson Institute, a National Security Institute, hired me and said the Defense Department wanted to give me an $85,000 grant for me to come to Washington…

Kevin Barrett: So they could understand how they’re ruling the world.

Michael Hudson: Yes. They didn’t realize that going off gold for the United States left other countries’ central banks with nothing to keep their foreign exchange reserves in except U.S. dollars, which meant U.S. Treasury bonds—loans to the U.S. Treasury, essentially. And so they looked at my Super Imperialism as how to do it book! And for the next four years, I was going back and forth to the White House and other government agencies sort of explaining this, and there was no attempt at all to to prevent this from being discussed.

In fact, I worked for a lot of brokerage houses who wanted me to explain to them what the foreign exchange effects of American dollarization and the Treasury bill standard were, and America’s free lunch. And Herman Kahn and others said, “Well, look, this is great. American imperialism is giving us a free lunch, and we’re able to get foreign countries not only to finance our debt, but our balance of payments deficit, which is mainly military.” So in effect, foreign central banks paid the foreign exchange costs of America’s military expansion all through the the Korean War, the Vietnam War and throughout the 1960s and 70s into the 80s, all over the world. And again, economics as a discipline doesn’t deal with politics, and political theory doesn’t deal with economics. And so there really was nowhere for me to fit this into the curriculum at all. But the book’s been translated into many foreign languages. There have been at least two editions in Chinese where it sold more copies than anywhere else.

Kevin Barrett: I can see why China would be interested in this.

Michael Hudson: Yes, because if you understand how America gets a free lunch through the dollar standard, if you understand how the IMF and The World Bank are impoverishing countries, then you realize why other countries are trying to de-dollarize, getting rid of the dollar, and why this is causing desperation in the United States, which now has to finance its own military expenses throughout the world with its own dollars. And that’s causing the dollar to go down. It’s causing inflation here. It’s causing other countries to break away from the U.S. orbit and leave the United States isolated. So the United States, when it went off gold in 1971, created a system that gave it an enormous amount of free lunch and foreign money for 50 years. But now that’s ending. It became so predatory and so abusive and so destructive of the Third World, destructive of other economies through the bad economics of the IMF, the bad economics of the World Bank, and essentially the destructive economics of neoliberalism from Reagan and Bill Clinton, Margaret Thatcher in England, and Social Democratic parties in Europe, that other countries are now changing and the whole world is splitting up and fracturing geographically, largely as a result of financial factors, monetary factors, and balance of payments issues. And all of a sudden, the whole emptiness of the way in which economics is taught in the United States is changing.

Kevin Barrett: Well, I guess that’s a good sign. But the good fortune for your book may not necessarily be good fortune, certainly not for the U.S. Empire, or maybe not even for the world. So the first question that arises after reading your book is: If at this point this new block of Russia and China—and Iran is on their side—and various other countries are interested—if this new bloc is going to try to break out of the dollar scam that you describe in the book, the biggest question is, why hasn’t anything like this happened before? Because as you describe, before World War Two, it was just kind of taken for granted that the the country that runs a huge deficit and gets into debt, ends up at the mercy of its creditors. And somehow the U.S. has flipped that around, especially after Nixon went off the gold standard. And rather than the world responding the way that all countries did prior to World War Two by pursuing their own national interests, it seems that most of the world has spent many decades accepting a grossly unfair system in an unprecedented way. So why has the reaction been so bizarre after World War Two, when before that it would have been unthinkable?

Michael Hudson: Well, all along, other countries realized that the system was unfair. General de Gaulle explained how it was unfair already in the 60s. The problem is, in order to have an alternative, there had to be a critical mass. And that meant a critical economic mess. The United States had one way of convincing other countries to go along, saying, “Well, we’ll wreck your economy if you don’t follow our rules and we’ll wreck your economy by doing what we’re trying to do to Russia and China and other countries today.” By imposing economic sanctions and by sanctions, they meant: “You need our exports and you need our market. Where are you going to sell your goods except to wealthy Americans? Where are you going to get your food except from American farms?” Other countries weren’t able to feed themselves, and they weren’t able to find a market because all of the markets were plugged in to U.S. consumption and U.S. foreign investment, and other countries weren’t willing to take the step towards public infrastructure investment themselves. There was somehow an idea that if you privatize infrastructure, it’ll become cheaper. And of course, that’s not the case. It’s loaded down with debt and becomes a monopoly and becomes more expensive.

Michael Hudson: Well, it took 50 years for other countries to develop to the point where two years ago, when the United States imposed agricultural sanctions on Russia, Russia said, “Okay, we’ll make our own cheese, we’ll grow our own grain.” And now two years later, Russia is the largest agricultural exporter in the world. Well, that wasn’t the case during the Cold War years as a result of the awful collective farm system that was over there. Same thing with China. Thirty years ago, China had not developed an ability to produce high technology, goods, cars, aircraft, electricity. It took a long time for other countries to develop. And fortunately (for China and Russia) you had Bill Clinton and George Bush and Obama essentially promote the offshoring of American industry. They pushed American companies to say, “Why hire American high wage labor when you can hire foreign labor?” And the foreign countries have all had their currencies decline, largely because whenever a country has to pay debt, it throws its currency onto the foreign exchange market, and the currency goes down. And what’s really devalued when a country lowers its exchange rate is the price of labor. So all of a sudden, the result of this dollar standard and IMF pro-creditor policy was to make labor outside the United States much less expensive than labor in the United States.

Michael Hudson: So American industry began to move to Asia, not only China, but also other countries in Asia. European industry did the same. And all of a sudden China said, “Well, you know, we’re quite happy to have you come in and build factories here and use our low wage labor. But you have to show us how to build the factory. You have to share your technology with us.” And so the American companies were glad to share their technology since the 1990s and (especially) since China joined the World Trade Organization around 2000. And now other countries say, “Okay, thank you for the technology. We really don’t need you anymore. We’ve we’ve got rich enough exporting to your market. We’ve got (to the point that) we can rely on each other for our own market. We can create our own currency. We don’t need dollars. We have our own printing presses in our countries. We spend our own currencies, yen or or whatever.” And so you can see how all of this has unfolded. And basically, that’s what my book Super Imperialism is about, how this process unfolded and left America all of a sudden without industry and as a debtor country.

Kevin Barrett: And what were they thinking when Clinton and subsequent presidents and the people behind them decided to go ahead and basically export the U.S. productive capacity and move the factories abroad? Did they really believe that was sustainable? Or—there’s a conspiracy theory out there that there are these evil globalists who are out to destroy the United States? Many Trump supporters believe in that. Of course, the Trump supporters also believe that the system you described is actually working against the United States, that the U.S. has been totally generous and throwing away all its money to these ungrateful other countries and so on and so forth. So but getting back to the issue of exporting U.S. productive capacity, why did they do that?

Michael Hudson: Well, you asked whether they didn’t see where it was leading? That’s the wrong question to ask. They didn’t care! The time frame of corporate investors is usually three months to one year. All they care about is the next year. That’s what their salaries are based on. So they knew exactly where it was leading. They didn’t care, because they said “we’ll be retired by then. We want to make as much money as we can as quickly as we can. Our salaries as CEOs are based on how high we can push the stock price. Let’s push the stock price high. We’ll get our bonuses, we’ll get our high salaries, and even if it collapses later, by that time we’ll be retired as multimillionaires.”

Michael Hudson: And there was also something else: They wanted to hurt labor. The Democratic Party has always looked at labor as what Hillary Clinton said: White Labor is deplorable. Employers don’t like Labor. There’s a class war and Clinton —like Tony Blair in England—Clinton revived the class war against Labor. He threw all of his weight behind corporate industry. And the Democratic Party, ever since Clinton and Obama, essentially became the party of Wall Street and large corporate America and the oil industry and foreign investors. And their business plan is to make money as quick as they can, and take their money and run.

Michael Hudson: And so it was perfectly logical to them. Of course, they knew what was happening. But to them, the fact that they were getting rich and labor was getting further and further in debt was actually a bonus. Because they’re really very nasty people. Their ideology is nasty. They want to get rich by making other people poorer. That’s their strategy. The whole business plan of the United States economy for the last 20 years is for the wealthy one percent to get the 99 percent in debt, and for American investors and banks to get Third World countries in debt, and then say, “you have to lower your wage rates, you have to stop unionization, you have to essentially just provide low priced labor.”

Michael Hudson: Clinton and all the subsequent presidents, especially Obama, essentially forced other countries to go it alone, which was the opposite of creating an empire. You can’t have a unipolar single global economy if you force other countries to remain in your empire only by impoverishing their own labor force. At some point they’re going to push back and they’re going to say “we don’t want to be impoverished.” And that’s exactly what’s happening, week after week and month after month, in today’s news.”

Kevin Barrett: And in today’s news, we see claims that this new Democratic administration wanted to change things and push these big infrastructure projects and engage in a certain amount of Bernie Sanders style redistribution and so on—you know, claims that the Democrats were sort of revitalizing the American Left such as it is. You write in a new article about the demise of the Democrats that today’s U.S. political duopoly features the Democrats as having the key role of protecting the Republicans from attacks from the left. And that’s basically all they do. So I imagine you weren’t particularly surprised when these ambitious Bernie Sanders style proposals have pretty much all fallen by the wayside.

Michael Hudson: There was never a chance of them taking place, because the philosophy of the Democratic National Committee that really runs the party is: Well, if we do have infrastructure, it has to be as a giveaway to monopolies that are going to get rich off government grants.

Michael Hudson: There are two kinds of infrastructure spending. The United States in the late 19th century developed the whole philosophy of infrastructure spending. And Simon Patton, who was the first economics professor in the United States at a business school—he was a business school professor at Wharton School—said: “Infrastructure is a fourth factor of production alongside labor, land and capital. But the purpose of infrastructure isn’t to make a profit, it’s for the government to invest and provide low cost essential needs education, transportation, communication and to provide low cost infrastructure so that the American industrialists can employ labor that doesn’t have to pay a high cost for education, doesn’t have to pay a high cost for health care, doesn’t have to pay a high cost for communications or cable TV or telephones or anything else.” Well, all this changed after the 1980s with the neoliberalism of Margaret Thatcher and Reagan and Bill Clinton.

Michael Hudson: They said: “We want to privatize infrastructure instead of having the government provide low cost infrastructure. Our political campaigns are paid for by the big monopolies, and we’re going to give a Comcast and Spectrum the right to charge huge economic rents from cable TV. We’re going to turn our free public roads into toll roads like the Indiana Toll Road. We’re going to turn over the streets and parking meters, we’re going to privatize them, as Chicago did by privatizing its’ meters. We’re going to make America the highest priced economy in the world. And all (the wealth of) this high priced economy is going to go to infrastructure monopolies. And so the the original concept of the Biden plan, essentially the Democratic Party’s plan, is to give its campaign contributors monopoly rights to infrastructure. It’ll be like pharmaceuticals, where the American government will pay the cost of developing a pharmaceutical and then it’ll give it to a drug company, whoever is its biggest campaign contributor, for $1, and let the drug company make half a trillion.

Kevin Barrett: That’s pretty much what they’ve done with the COVID vaccines.

Michael Hudson: Yes, that’s exactly right. The government paid for developing the vaccine, told its campaign contributors “You can make all you want here, and this is wonderful. Now we can make the Third World countries pay so much money for the vaccine that their currencies will go down and we can employ their labor even more cheaply and get their raw materials even more cheaply.”

Michael Hudson: So that’s part of the system. Infrastructure as the Democratic Party sees it is a travesty of what American infrastructure was a century ago. And they don’t realize that the way infrastructure is financed, and what it’s priced for, is the key. Of course, Bernie Sanders said, “look, American companies won’t have to pay their employees so much money if the government pays for all of their medical costs.” Right now, eight percent of America’s GDP goes for health insurance and health care. That’s higher than any other country, and the health care is much worse because it’s all done for profit and done as cheaply as possible, and it’s been financialized.

Kevin Barrett: So the angry reaction to this that we would expect has to some extent developed, as abroad this new bloc with Russia and China is pushing to de-dollarize, which could take down the empire by preventing the U.S. from running these massive deficits to support its military occupation of so much of the globe. But here in the United States, the angry reaction to it has come through the Republicans and the Trump movement. And those people, of course, are even less interested in keeping public infrastructure cheap and pushing through Bernie Sanders style proposals. They’re even more interested in giving their contributors monopoly rents to make fabulous fortunes by ripping people off. So where will the well-informed, angry reaction to this come in the U.S. political system? Do we need a third party? Or could the Trump movement morph into a more enlightened angry populist movement?

Michael Hudson: You’ve stated the problem very clearly. What you just said is exactly what’s occurring. It’s almost impossible to start a third party in the United States. Bernie Sanders looked into that years ago. And the way that the state laws are written really blocks any third party from getting onto the ballot. The Democrats and Republicans have small print in the laws such that it essentially blocks anyone from doing anything. So when you have someone like Bernie coming in as an independent, he has to caucus with either the Republicans or the Democrats. I certainly don’t see the Trump Republicans being any better, because they’re just like the Democrats. I think of them as the same party. There’s really no difference. But they have different constituencies, and they both are financed by the same campaign contributors—by Wall Street, the large corporations, oil and gas, the pharmaceuticals industry. And it really doesn’t matter… For instance, if you look at last month’s elections for mayor in Buffalo, New York, you had the Democratic Party candidate being a left winger. And so the Democratic National Committee and the Democratic National Party backed the Republican, saying, “We’ll back the Republicans against any follower of Bernie or any progressive.” So you have the duopoly firmly in control, very much like the Roman Senate was in control at the end of the Republic and was able to block any kind of progressive movement. And you have the big media, the New York Times, the Wall Street, New York Times, The Washington Post and the major TV networks just not talking about the kind of things that we’ve been talking about for the last half hour, certainly not.

Kevin Barrett: Well, the progressive movement used to be quite different from what it is now. In the late 19th century, in the early 20th century, it was much more interested in these kinds of issues that you raise. Today, it seems like the so-called progressives are mostly interested in gender pronouns and racial hysteria. Do you think that could be a deliberate strategy by people with a lot of money who have the money to hire Edward Bernays style PR experts in order to hoodwink the average people and get them paying attention to the wrong things?

Michael Hudson: I think that’s exactly what’s happened. The question is, if you were to have a third party or a progressive movement, what are they going to talk about? They’re going to talk about economics, about wages, about economic issues, about debt. And how do you, how do you prevent any movement from coming and talking about economics? Well, the Democrats from already in the 1960s, but especially from the 1980s, said, “Okay, let’s divide the electorate into hyphenated Americans.”

So in the 1960s, you had Italian-Americans, Greek Americans, Irish-Americans. Now, if you just say it’s divided by gender, by ethnicity, by race… what all these different hyphenated identity groups have in common is they’re all wage earners. But the one thing you don’t talk about is wage earners. If you can get people to think of themselves in terms of ethnic or racial or gender groups, then they won’t think of themselves as having the common denominator of being wage earners, debtors and taxpayers and consumers. And if they think of themselves as consumers and debtors, then they’re going to want debt relief, they’re going to want an end of monopoly pricing for consumers. They’re going to want progressive taxation and to shift the tax burden on to the billionaires, not onto themselves. And both the Democrats and Republicans want to make sure that doesn’t happen. So the Republicans have become the party of white working class labor, while the Democrats say, “well, they’re deplorables, we’ll take all the rest and we’ll play them off against each other.”

I don’t know how long that can last before people wake up and say, “Wait a minute, we all have a common problem and the common problem is debt. We’re all in debt. We’re struggling to make a living, our wages aren’t going up while profits are going way up. We’re having to pay more and more to the monopolists, and we’re afraid to quit our jobs and complain about working conditions because then we’d lose our health care and we’d fall behind in our rents and be evicted or we’d lose our homes. This is not the situation we were promised in 1945 after World War Two.” And they’d all say “there is an alternative.”

Well, the Democrats and Republicans have have adopted Margaret Thatcher’s slogan “There is no alternative”: TINA. And as long as people believe there is no alternative, they’ll just somehow blame themselves and they’ll think, Well, gee, we’re a failure. We haven’t succeeded. And they don’t realize that the deck is stacked against them, and they have to change how the economy works systemically. And now that there is an alternative in China and other countries, they can say, wait a minute, it doesn’t have to be this way. Our wages can go up. What China does that makes it so unique is it hasn’t left the financial system and money creation in the hands of banks. The government creates the money and the government can write down debts. So when you have big companies going into debt to essentially expand the economy, the Chinese government can just write it down.

Michael Hudson: The U.S. government can’t have Chase Manhattan or Citibank or Bank of America write down the debts because they’d lose all the political campaign contributions and the banks would create a crisis. So essentially, what’s blocking the United States recovery is financialization. And as long as you have this financialization, which is also occurring throughout the world and is causing a whole crisis in the Third World today—as long as you have financialization, you’re going to have a slow crash. You’ll be getting more and more austerity until you end up looking like Argentina.

Kevin Barrett: Well, “financialization” is a kind of a fancy word that seems to describe the transfer of the economy from Main Street to Wall Street. And it occurs to me reading your work—and one of the great things about your work, of course, is the sweep of history where you can touch on these historical examples from the Roman Empire and even back to biblical times—it occurs to me that the two basic underlying scams at the heart of these processes that you describe are, on the one hand, compound interest, which of course, is mathematically unsustainable, money growing faster than the physical things it can represent; and rent extraction, unearned rent extraction: Somebody has a piece of paper that says, “I own this land or whatever, I own this money, I own this infrastructure, and so you have to just pay me for sitting here on my butt doing nothing because I have this piece of paper I can wave in your face.” And these two kinds of unearned wealth seem to be at the root of so many of these problems.

Kevin Barrett: I’m Muslim, and we’re quite fervently opposed to usury, although most Muslims don’t have the faintest concept of what’s really going on, what’s really at stake. But that core principle of usury being a horrendous sin and something that just needs to be stomped out, and that God and his prophet and by extension the community of his prophet, has to be at absolute all out war with usury, meaning all forms of lending and interest, for all of eternity—that principle is still there. So I’m wondering if you think that enlightening people to this (can help), just like people, when they understand a Ponzi scheme, can avoid being taken in by it. At some point, will humanity awaken and recognize that unearned rents and compound interest need to be abolished?

Michael Hudson: Well, this is what classical economics was all about in the 19th century. Everything from Adam Smith to David Ricardo to John Stuart Mill to Marx, to Alfred Marshall to Thorstein Veblen—the whole 19th century tried to get rid of land rent and economic rent by the landlord class. John Stuart Mill said economic rent is what landlords make in their sleep. It’s unearned income. A classical idea of a free market was to free markets from economic rent and from monopoly rent, from land rent and from natural resource rent. And the idea was that taxes should essentially siphon off all the rise in land values and natural resource values and economic rent. And that was where the world was moving towards until World War One. Everybody expected the governments to play a rising role. And it was in the United States and Germany where government was playing the most active role in promoting industrialization and preventing economic rent, by the U.S. antitrust laws and other countries’ similar laws. These became the leading industrial nations.

Kevin Barrett: Today, economic rent is being opposed primarily in China and the socialist countries. And now it’s called socialism. But it used to be called a free market by Adam Smith. And so this is one reason why in the last 30 years, they don’t teach a history of economic thought in the economics curriculum anymore. They’ve replaced it with mathematics. And so people are not even aware that the whole idea of a free market has turned away from a market that’s free from rent extractors, free from private banking and credit, towards a market free for landlords to get as much as they can and not pay taxes on it, free for the banks to make financial interest and not have to pay income tax on it.

Michael Hudson: One of the big fights over the Biden so-called social infrastructure plan was to say: The most unfair economic giveaway of all is the giveaway to the financial sector in the form of what’s called carried interest, which means trading speculative gains by large banking firms that are manipulating the market. And of all of the proposals that Biden had to tax financial gains, this was the first to go, because the financiers said, “If you want us to continue giving money to your candidates to beat the Republicans, then you’d better drop anything that’s going to attack Wall Street. Remember Democrats, you were the party of Wall Street.” And so they did that.

Michael Hudson: The next most popular proposal that Biden had originally made in his plan was to forgive student debt. Well, again, the corporations said, “Wait a minute, you’ve got to have student debt being paid because the students have to pay the student debt. They’re going to have to go to work and go into the labor force and take whatever we are willing to pay them in order to not fall behind in their student debt.” So essentially, what is holding down wage rates and holding down working conditions in the United States is finance and economic debt.

Kevin Barrett: And the rent extraction seems to be also happening on the other end with the current inflation, which is not just the result of all of this COVID money that’s been blasted out into the world, mostly through through the big corporations and banks, but also the monopolization of the various goods and services that we all buy. That’s happened at the same time that the small businesses have been driven out of business by COVID. And now Wal-Mart and Amazon are the only options. And since they have de facto monopolies, they can charge whatever they want. And hence prices are rising very quickly. Do you think that that’s a big factor behind inflation, this consolidation by the big retail outlets?

Michael Hudson: Sure. The last year and a half since COVID have been a bonanza for the one percent. The stock market and bond market have gone way up. Corporate profits have gone way up. And for the 99 percent, for the workers, what’s gone up is their debt. They’re talking about eight million families about to be evicted from their homes, who were unable to pay rent while there was the COVID crisis and they lost their jobs, especially low income jobs. And the moratorium on back rents and back debt is supposed to expire in February, and it’s already in fact expiring in some states. And you’re going to have millions of people thrown out of their homes. And that’s why you’ve had the private capital funds use this money that they’ve cleaned up in the stock and bond market in the year and a half of COVID to buy property. And now I think over a quarter of all of the homes that are being bid up in price are being bought by private capital companies. The idea is they want to turn America from a country of homeowners into a country of renters. That’s their business plan, and they’ve vastly succeeded. Obama started the process by not, by bailing out the banks and breaking his campaign promise to roll back the junk mortgages to realistic mortgages. Instead, he met with his campaign contributors. He invited the Wall Street bankers to the White House and said, “I’m the only guy standing between you and the mob with pitchforks. But don’t worry, I’m on your side. My job is to deliver my voters to you.” And that’s just what he did.

He immediately evicted two and a half million homeowners. He did not write down the debts, and he did not throw a single Wall Street bank crook in jail, despite their massive rip offs and financial fraud. He did not even take over the insolvent banks like Citibank, like Sheila Bair, who was head of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, had urged him to. The problems we’re having now in a way can be traced back to the Obama administration. The Federal Reserve has been single handedly financing the stock market and the bond market. The government has been giving away monopoly privileges to increase profits, to help support stock and bond prices, and that’s been a disaster for the economy at large. But again, I’m not sure where one can fit this into the academic curriculum, which is why most students decide that economics really wasn’t very interesting to get a degree in and went into other subjects like anthropology or sociology or whatever. And that’s why you’re talking about these problems on radio and the internet, but it’s not being talked about in the New York Times or The Washington Post.

Kevin Barrett: Well, here’s a question for for you, since you’re an economist. This is something that I wouldn’t be able to figure out myself. My dad was a professor of finance as his final job, his last job, and we used to discuss these matters. He was a pretty conservative, common sense guy who thought differently because he’d actually run a business and then retired and became a professor of finance. And he thought that a lot of the profession was overly theoretical. He believed in the regression to the mean: that is, if the price earnings ratio is out of whack, it’s going to have to return back to the norm and so on. And so one of those ratios that I believe is a little out of whack right now would be the percentage of people’s incomes they’re paying for their housing compared to their overall income, right? Supposedly it always has to return to some—I don’t remember precisely what the numbers are here, maybe you do. But the question would be: If these rent seeking oligarchs succeed in buying up enough of the U.S. housing stock, are they going to be able to permanently change that ratio so that it’ll never regress down to the mean? Maybe you have the right numbers. But let’s just say normally people spend 25 to 30 percent of their income on housing, and let’s say it’s up to 35 to 40 percent now. Can they permanently change that and force people to continue to pay 35 to 40 percent of their income for housing if they buy up enough of the housing stock? Or do you think it’ll inevitably bounce back to the historical levels?

Michael Hudson: I don’t see it bouncing back unless there is a change in the tax system. And if there was was a change in the tax system, the whole financial system would collapse, because 80 percent of bank loans in the United States are mortgage loans, and these mortgage loans to homeowners are guaranteed by the government up to the point where they absorb 43 percent of your income. And this is the legal maximum in the United States. Well, imagine that Fannie Mae, the government mortgage insurance agency, says we will guarantee the loan so that you will not make money, but you can’t take more than 43 percent of the income because otherwise it would be unstable. When I came to New York in 1960, there was a rule for banks. Banks would not make a mortgage loan for a home that absorbed more than 25 percent of the borrower’s income. So already we’ve had the income cap go from 25 percent to 43 percent. Well, just imagine the status of workers now if 43 percent of their income goes for housing. In New York City, it’s often 50 percent of their income.

Kevin Barrett: In San Francisco, it’s 200 percent. (laughter)

Michael Hudson: This is why the United States cannot industrialize as long as the house prices absorb this high a rate of income, and as long as the banking sector is supporting this, and as long as the political parties say we will not tax real estate so that all of the rising land value will be able to be pledged to banks to pay interest instead of to pay taxes. Essentially, it’s the (lack of) taxing of real estate in the United States that has subsidized the increase in housing prices, because housing prices are worth whatever a bank will lend to buy a house. If you have to go to a bank, and if they lend more and more and this money isn’t taxed away, the price is going to go up. So you have the government policy, the bank policy, all trying to promote this high diversion of income into paying land rent. Again, this is the exact opposite of what Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill and classical economics and the whole 19th century had advocated. This has priced American labor and industry out of world markets.

If you have to pay 43 percent of your income for rent, then even if the government were to give you all of your goods and services for nothing, all of your food, all of your clothing, all of your transportation for nothing, you’d still have to pay so much money for rent and for health care that you couldn’t compete with labor in Asia or the Third World or even Europe. And so this is what has essentially excluded the United States from having a successful empire. It’s the greed of the financial sector, basically, and the takeover of the government by the financial sector here as happened under Margaret Thatcher in England and then Tony Blair. You’ve had both countries essentially enter permanent austerity programs, and the only way to cure this is for housing prices to go down. But if the housing prices go down, then the banks will go broke. That’s why Obama said he had to support the banks: because if he’d actually lowered the housing prices to realistic levels, that would enable America to survive, but the banks would go under. Until you’re willing to restructure the banking system, you’re not going to be able to industrialise the American economy.

Kevin Barrett: Ellen Brown has been on the show many times, talking about the need to make banking a public utility. And I recently read Stephanie Shelton’s The Deficit Myth. She argues that we can fix all kinds of problems and bring back full employment and have all sorts of goodies simply by having the government spend more money. This is the modern monetary theory position. And maybe that is true to a certain extent in the U.S. due to these privileges that you describe in Super Imperialism. I doubt if it’s nearly as true anywhere else, for all these reasons that you’ve been describing. Do you think that if the U.S. ever does opt for more of a Bernie Sanders style modern monetary theory approach, would they quickly run into the limits of spending money due to these international factors?

Michael Hudson: No, there’s no limit to how much domestic money you can create to spend domestically. Right now, the banks are creating all the credit. And Stephanie says you don’t have to rely on banks to create credit. The government can simply create the credit instead of the banks, and it doesn’t have to charge interest. It doesn’t have to go into debt. Stephanie was my department chairman at the University of Missouri at Kansas City, and we’ve gone around the world together giving speeches and lectures on this. Her logic is quite correct. The problem is that modern monetary theory has been taken over by somebody in a much stronger position than Stephanie—by Donald Trump. And Donald Trump said, “We can just create all the money we want.” And he cut taxes and went on spending and he was willing to do it. Stephanie was the economist for the Congressional Budget Committee and was an adviser to Bernie Sanders. But the Democratic Party gimmick the election to make sure that Sanders and people who were advising him would not have a chance of getting into government. And they chose the Donald Trump version of modern monetary theory, where the government creates money and gives it to the banks. This quantitative easing has created trillions and trillions of dollars, but it’s all been used to buy stocks and bonds and package mortgages. It hasn’t been used to spend into the economy, which is what Stephanie wants. So the question is: if the government’s going to create money, is it going to be spending into the economy, which is what the MMT group that I’m a member of is advocating? Or is it going to be given to Wall Street just to support stock and bond prices and promote financialization? That’s really the the great issue financially in economic policy today.

Kevin Barrett: Ok. And I think that’s a good place to end it. So thank you so much, Michael Hudson. I appreciate your fantastic landmark book, Super Imperialism, as well as your ongoing columns, which people can find at the Unz Review, that’s U.N.Z., where I’m also a columnist and probably where many of you are listening to this radio show. I appreciate your great work, and I hope that down the line you can come back on the show and we can talk about some promising solutions, or at least some more positive political developments than we’ve seen so far.

Michael Hudson: Well, you’ve asked all the right questions, and our discussion shows that there are a lot of powerful interests preventing a solution. So I’m not sure when we’re going to have a realistic discussion about that, but it is important for people to know that there is an alternative.

Kevin Barrett: Ok, well, thank you. Michael Hudson, great conversation. I look forward to talking again sometime. Take care.

Michael Hudson: Thank you for inviting me.

Read more:

https://www.unz.com/kbarrett/falling-into-line-turning-endless-deficits-into-a-power-base/

Read from top.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW √√√√√√√√√√√√!!!