Search

Recent comments

- crummy....

2 hours 50 min ago - RC into A....

4 hours 43 min ago - destabilising....

5 hours 47 min ago - lowe blow....

6 hours 18 min ago - names....

6 hours 55 min ago - sad sy....

7 hours 21 min ago - terrible pollies....

7 hours 31 min ago - illegal....

8 hours 42 min ago - sinister....

11 hours 5 min ago - war council.....

20 hours 50 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

bungled sponsorship...

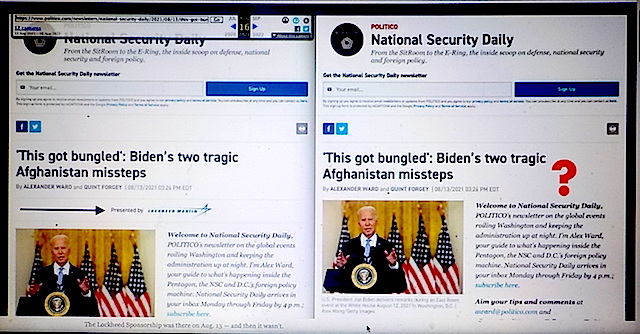

Politico appears to have ended, or is trying to hide, a sponsorship deal between Lockheed Martin, the largest weapons manufacturer in the United States, and its popular newsletter National Security Daily. Evidence that the relationship had ever existed at all then vanished from Politico’s website.

Since late March, Lockheed had been listed as a sponsor of the daily newsletter — a popular read among Washington’s foreign policy elite that previously went by the name Morning Defense. Prior to that, the sponsor was Northrop Grumman, America’s third-largest weapons manufacturer.

On the morning of August 16, Quincy Institute senior adviser and Responsible Statecraft contributor Eli Clifton called attention to this relationship in the context of the withdrawal from Afghanistan in a tweet that then went viral; the sponsorship was also a subject of mockery on Reddit. The Monday edition of National Security Daily that was released that afternoon no longer listed Lockheed as the sponsor, and neither have all subsequent editions of the newsletter published since that date.

Moreover, Lockheed’s sponsorship also disappeared from all previous editions of the newsletter in Politico’s archives. But internet archiving tools show that the sponsorship was still listed prior to August 16.

One example is the May 10 edition of Morning Defense. Before August 16, “Presented by Lockheed Martin” appeared beneath the headline and byline. Halfway down the page, two Lockheed advertisements could also be found, one promoting its F-35 fighter aircraft as the “cornerstone of the U.S. Air Force fighter fleet.”

But now, neither the sponsorship nor the advertisements appear on the page. The same pattern emerges for all editions of the newsletter dating back to at least March if not before, and no editorial note is attached recognizing or explaining the change.

There is clear evidence that August 16 was the decisive date. The Lockheed sponsorship was still present on the August 13 and August 11 editions of the newsletter prior to that afternoon; later that evening, they had disappeared from both.

Some of these changes were originally reported by Heavy.com on August 17, although that report only mentioned three editions of the newsletter, missing that the sponsorship had disappeared from all of those dating back to March.

It’s possible the sponsorship ended coincidently. It’s also possible Politico may have made a technical error, rather than deliberately attempting to scrub any evidence of its prior relationship with Lockheed from the internet.

Nonetheless, anyone who stumbles upon past editions of the newsletter today would have no way of knowing that the relationship between Politico and Lockheed existed at the time of publication, or in fact at all. At a moment of serious introspection about American foreign policy— and the ways in which the defense industry has long exercised an outsized influence in Washington — Politico appears to have tried to wash its hands clean.

Neither Politico or Lockheed returned multiple requests for comment clarifying whether their relationship had in fact ended, or whether the removal of Lockheed’s sponsorship from previous editions of National Security Daily was deliberate or a mistake.

Read more:

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW !!!!!

- By Gus Leonisky at 6 Oct 2021 - 5:17am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

dying for a self-licking ice-cream cone...

Institutional interests, including military budgets and self-preservation, will drive bad national security decisions every time.

Written by

Gareth Porter

There is a rapidly growing political demand for making American officials accountable for the failures of the Afghanistan War, with a focus now on the military leadership and top generals’ role in keeping forces there for 20 years despite all the signs they knew the war was unwinnable.

One indication of a new political stage for the issue is the fact that Afghanistan War veterans Republican Joe Kent, running for a House seat in Washington state, and Democrat Lucas Kunce, running for a Senate seat in Missouri, have both called for such accountability, questioning the war’s continuation despite evidence it could not be won. Kunce has said that the “right call” would have been to get out of Afghanistan in 2002 or 2003. Kent has charged that U.S. commanders in Afghanistan “have been lying for years, because they want to keep these wars going.”

This is the first time political candidates have suggested that the interests of senior military officials played a key part in prolonging the war in Afghanistan. The idea that national security institutions and their leaders pursue such parochial interests has been almost entirely ignored in past discussions, because mainstream foreign policy specialists have disapproved of it.

It wasn’t until the December 2019 release of the The Afghanistan Papers, a collection of confidential interviews with U.S. officials and other war insiders, that it was publicly revealed how official Washington continued to push the war despite their private reservations that it could be won.

But Morton Halperin, who was a senior official at the Pentagon and on the White House National Security Council staff in four different administrations, beginning President Lyndon Johnson in 1966, documented the existence of such institutional interests as a fact of political life in his classic book “Bureaucratic Politics and Foreign Policy,”the second edition of which was published in 2006.

Halperin identified the three kinds of interests that shape the positions taken by government institutions on national security issues: 1) budgetary resources, 2) the missions and capabilities defining their institutional identities, and 3) their internal staff morale. Using this frame can go a long way toward explaining the decisions made by the military services and the Pentagon over the last 20 years.

The Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan that exploded between 2005 and 2006 and continued in grow rapidly through 2008, became a serious threat to the institutional interests of the military services and the Pentagon. The Joint Staff at the Pentagon led by former staff director Gen. Stanley A. McChrystal, who had been named commander of U.S. and coalition forces in Afghanistan in 2009, developed an entirely new campaign plan that became the basis for his request for at least 40,000 more troops.

But the new strategy was doomed by critical weaknesses, the most important of which was the fact — admitted in McChrystal’s own campaign plan — that “key groups” in the country were supporting the Taliban as the only alternative to an Afghan government and security forces that these groups viewed as dependent on widely-hated, abusive warlords. The new campaign plan against the Taliban thus represented a big risk of embarrassing failure for McChrystal, the Joint Chiefs, and the Pentagon.

Furthermore, unexpected developments in Iraq in 2008 powerfully influenced their institutional calculus. The Iraqi government unexpectedly demanded a complete withdrawal of all U.S. troops from Iraq by the end of 2011, and President George W. Bush, fearing an even faster timetable for withdrawal in an Obama administration, signed the agreement with the Iraqi government in October 2008 pledging to withdraw all combat troops by that 2011 deadline.

The troop withdrawal from Iraq made the continued U.S. counterinsurgency war against the Taliban the Army’s primary mission. A 2009 Pentagon plan for restructuring the military budget around a “counterinsurgency” mission to justify a 14 percent increase in military spending was based on the assumption that U.S. forces, including the Army, would be deployed around the world in “stability operations” for the foreseeable future. But that plan for increased spending had originally assumed a semi-permanent U.S. military presence in Iraq and a smaller long-term presence in Afghanistan.

It was not only the Army’s interest in future funding, but also its choice of a central future military mission that was at stake in Afghanistan. The new Army Chief of Staff George W. Casey, who had previously been commander of U.S. forces in Iraq, predicted in a series of speeches in 2007 and 2008 that the military would be engaged with non- state actors and terrorist organizations for decades to come in what Casey called an “era of persistent conflict.”

As the U.S. troop presence in Iraq wound down, the Army’s role in Afghanistan became emblematic of its new mission and the rationale for continued high levels of budgetary support. Consequently, during and after the U.S. troop surge of 2009–2011, it proved impossible for the commander in Afghanistan to come up with accurate metrics that would show any real progress against the Taliban, as an NSC official later admitted. “The metrics were always manipulated for the duration of the war,” the NSC official said in a confidential interview made public by the Washington Post’s Afghanistan Papers in December 2019.

The use of phony metrics to sell the war was not new to cynical enlisted men in Afghanistan. They considered it one of the main features of what they called a “self-licking ice cream cone” or “SLICC”, which a popular glossary of military slang defined as any program that “appears to exist in order to justify its existence and produces irrelevant indicators of success.”

With institutional interests riding so heavily on the war in Afghanistan, it is not difficult to see how U.S. commanders in Afghanistan — all Army generals — had an overwhelming incentive to make false claims of progress in the war despite the clear evidence to the contrary. They were not only trying to make themselves look good; no doubt they believed, with good reason, that the continuation of the war itself depended on the confidence they were able to engender with those who held the purse strings in Congress.

The third primary institutional interest — internal institutional morale —was also well-served by the continuation of the war in Afghanistan, especially with regard to the officer corps of the Army, which dominated the U.S. military footprint. That was accomplished by rotating a large number of officers through the war for relatively brief periods, which meant that more of them could be promoted to higher ranks. This resulted in the U.S. Army having more four-star generals on active duty by 2020 than at any time since April 1945. As candidate Joe Kent put it succinctly, “Wars are good for generals. This is how they make their rank.”

That policy also resulted in cycling no fewer than eight U.S. generals through the position of commander of all U.S.-NATO forces in Afghanistan from 2003 through 2018. The military career of Gen. John W. Nicholson, Jr. was essentially shaped by the war: he served three different tours in Afghanistan for a total of five and a half years and retired as a four-star general in 2018 after two and a half years as the top commander.

The historical circumstances surrounding the decision to plunge ahead with war in Afghanistan and the deceptions used to support that decision, indicate that Halperin’s analysis of the three kinds of institutional interests that motivate policy can and should be used more widely for analyzing national security policy. That analytical approach can provide a more realistic understanding of what has driven other historical and contemporary national security policies — and how they can best be challenged.

Read more: https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2021/10/04/how-the-self-licking-ice-cream-cone-prolonged-the-20-year-war/

CIA journalism...

A high-flying German media giant is ahead on digital media but seems stuck in the past when it comes to the workplace and deal-making.

A high-level editor at the powerful German tabloid Bild was trying to break things off with a woman who was a junior employee at the paper. He was 36. She was 25.

“If they find out that I’m having an affair with a trainee, I’ll lose my job,” the editor, Julian Reichelt, told her in November 2016, according to testimony she later gave investigators from a law firm hired by Bild’s parent company, Axel Springer, to look into the editor’s workplace behavior. I obtained a transcript through someone not directly involved.

Just before the editor spoke those words, another woman at the paper had lodged a sexual harassment complaint against the publisher of Bild. But Mr. Reichelt’s relationship with the junior employee continued, she testified, and he was promoted to the top newsroom job in 2017.

Mr. Reichelt then gave her a high-profile job, one she felt she wasn’t ready for, and he continued to summon her to hotel rooms near the gleaming Berlin tower occupied by Axel Springer, she said.

“That’s how it always goes at Bild,” she told the investigators. “Those who sleep with the boss get a better job.”

[Update: Bild ousts editor after Times report on workplace behavior]

This account is drawn from an interview conducted in the spring by a law firm retained by Axel Springer for an investigation that quickly closed, clearing Mr. Reichelt. A spokeswoman for Axel Springer and Mr. Reichelt, Deirdre Latour, said the woman’s testimony included “some inaccurate facts,” but declined to specify which ones.

Mr. Reichelt did not, as he feared, lose his job when his relationship with the woman, as well his conduct toward other women at Bild, became public. Instead, Mr. Reichelt, who denied abusing his authority, took a brief leave and then was reinstated as perhaps the most powerful newspaper editor in Europe after the company determined that his actions did not warrant a dismissal.

Bild is the flagship publication of Axel Springer, a titan of German media since after World War II. The company is now focusing much of its energy on the United States. American media types may know it mainly for its leader, Mathias Döpfner, a charismatic chief executive who moved more swiftly than most traditional publishers to embrace the internet.

In 2015, the company bought Business Insider (now called Insider) for $442 million. This summer, it announced that it had purchased Politico for $1 billion. Axel Springer aims “to become the leading digital publisher in the democratic world,” Mr. Döpfner told me in an emailed statement.

But as the reports on the Bild investigation suggest, the company’s workplace culture may be stuck in a time warp. And as Axel Springer moved across the Atlantic this summer on its spending spree, the company’s aggressive and — a key American executive said — “sneaky” style of doing business generated friction.

To get a feel for the German company now emerging as a major player in American, and global, media, it’s important to understand the man for whom it was named, a towering figure in postwar media.

Axel Springer was a fierce anti-Communist and supporter of Israel, and his papers were hostile to the student leftists of the 1960s and 1970s. The Red Army Faction bombed Axel Springer’s offices in Hamburg in 1972. In 1974, the Nobel Prize-winning novelist Heinrich Böll published “The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum,” about a woman whose life is ruined by an aggressive reporter for a Bild-like paper after she has an affair with a left-wing militant.

Bild’s politics are now center-right, but have grown sharp-edged under Mr. Reichelt, a former war correspondent. The tabloid initially welcomed Syrian refugees, then turned bitterly critical of immigration (though it is also hostile to the far-right AfD party). A Washington correspondent for Bild complained, in internal Slack messages that subsequently leaked, of a slant toward Donald Trump in the coverage of the 2020 U.S. presidential debates. The paper has also attacked the German government’s Covid restrictions and its main public health expert.

It seems the old battles have left Axel Springer forever on its guard against potential enemies. That quality can seem slightly out of place in 21st century Germany, where the company publishes not just Bild but also the broadsheet Die Welt, and is the owner of a lucrative classifieds business. When I visited Berlin this summer, Mr. Reichelt took me to a restaurant in his armored car.

“They have a bunker mentality,” said Moritz Tschermak, the author of a recent, critical book on Bild, “and at the moment the bunker mentality is quite strong.”

Mr. Springer, who died in 1985, also had a personal life that might be called colorful. His third wife had previously been married to his next-door neighbor. His fourth wife was the next-door neighbor’s second wife. His fifth wife, Friede Springer, had been the family’s nanny. When he left the company to her upon his death, she surprised her many doubters by emerging as a force in her own right. She is now the vice chairwoman of Axel Springer’s supervisory board.

Her longtime ally is Mr. Döpfner, a music scholar turned editor. He joined the company in 1994 and took over Die Welt in 1998. Ms. Springer made him the chief executive in 2002, after she had waged a successful legal battle against challenges to her leadership by others in the Springer family.

Mr. Döpfner, who once described himself as “a mixture of aesthete and carpet salesman,” is an enthusiastic deal-maker who stands 6-foot-7. Under his leadership, Axel Springer has had elaborate holiday parties, including a disco night in 2018 that included 10 D.J.s, 512 disco balls and a joint performance by the Village People and company board members. His dance moves at one party left an impression on the company’s slacks-wearing partners at Politico. He also owns one of Germany’s leading collections of female nude paintings.

Mr. Döpfner’s biggest impact has been in pushing the company online. In 2012, he dispatched members of the mostly male senior executive team to Silicon Valley, where they roomed together, made a study of the new media economy and produced a goofy video that showed them sharing king-size beds. The goal was to transform Axel Springer into a global giant able to solve the riddle of how to profit from digital journalism.

Early results were uneven, including investments in the recently troubled Ozy Media. Mr. Döpfner’s biggest quarry, The Financial Times, slipped through his fingers in 2015. Axel Springer consoled itself with the purchase of Business Insider, which has thrived under its ownership. And Mr. Döpfner made progress on a campaign to force Google and other tech giants to pay publishers for content.

In 2019, the American private equity firm KKR bought more than 40 percent of the company and took it private, an endorsement of Mr. Döpfner’s strategy. In 2020, Axel Springer bought the newsletter company Morning Brew — and set its sights on Politico.

Last fall, Ms. Springer offered Mr. Döpfner a reward for his decades of service: $1.2 billion of Axel Springer stock. She then sold him a bit more, making him a billionaire and major shareholder. The shares came with the voting rights to her remaining stake, making it clear that the company is Mr. Döpfner’s now.

That is the backdrop for the dual dramas that consumed Axel Springer in 2021.

The first was the investigation into Mr. Reichelt, the editor who is also the face of a new television network Bild has started. Der Spiegel reported in March, under the headline “‘Screw, Promote, Fire,’” that Axel Springer had hired a law firm to investigate claims that Mr. Reichelt had created a hostile work environment for women; the publication did not report all the details of the claims. Der Spiegel described “the Reichelt system,” in which “the editor in chief was said to have invited female trainees and interns to dinner via Instagram. Young female employees were sometimes quickly promoted. Their fall from grace was similarly rapid.”

His leave of absence lasted all of 12 days. When Axel Springer announced that the investigation was over, it issued a statement saying that it had examined “accusations of abuse of power in connection with consensual relationships and drug consumption at the place of work. Contrary to rumors reported in several media titles, there were no accusations of sexual harassment, and the investigations did not discover any evidence whatsoever of sexual harassment or coercion.”

The statement went on to say that unspecified “mistakes” were outweighed by “the enormous strategic and structural changes as well as the journalistic achievements that have taken place under the management of Julian Reichelt.”

The statement included an apology: “What I blame myself for more than anything else is that I have hurt people I was in charge of,” Mr. Reichelt said. He returned to his post, but with a woman, Alexandra Würzbach, as Bild’s co-editor. She was given responsibility for personnel and the Sunday edition.

Axel Springer has sought to keep details of the investigation’s findings out of the German press. Mr. Reichelt sued Der Spiegel in March, and won a minor legal victory forcing the publication to append a statement to its article acknowledging that Mr. Reichelt said he had never received the questions sent to Axel Springer’s spokesperson.

In April 2018, the business newspaper Handelsblatt was prepared to report on alleged conflicts of interest in Mr. Reichelt’s relationship with a woman at a public relations agency, Der Spiegel reported this year. The article was killed after a call from Mr. Reichelt, a person involved in the process said. (A Handelsblatt spokeswoman did not respond to an emailed inquiry.)

This year, Juliane Löffler, a reporter at the German publisher Ippen, along with three other members of Ippen’s investigative team, worked on an investigation of Mr. Reichelt’s conduct in the hope of publishing an article with more details on what had taken place at Bild. In the course of reporting, Ms. Löffler and her colleagues gained access to some of the same documents that I reviewed in recent weeks, as the Ippen article was nearing its publication date. Then, on Friday, Ippen told its investigative unit that it was killing the story.

The directive came from Ippen’s largest shareholder, Dirk Ippen, according to correspondence from a company official that I obtained. Ms. Löffler and her fellow reporters objected, writing in a letter to company management that “no legal or editorial reasons were given” for stopping their reporting.

An Ippen spokesman, Johannes Lenz, said that Ippen had decided not to publish the story “to avoid the appearance of combining a journalistic publication with the economic interest of harming the competitor.”

The documents I saw paint a picture of a workplace culture that mixed sex, journalism and company cash. The trainee who gave testimony in the law firm’s inquiry said that when she was moved around the newsroom, another Bild editor told her he was tired of having to take on women with whom Mr. Reichelt had had relationships.

That editor did not respond to an inquiry for this column; the woman whose testimony appears in the investigation report declined to comment, and The New York Times is not naming her because the interview transcript includes her request for anonymity.

The woman also testified that when the expenses for the job she’d been placed in exceeded her salary, she complained to Mr. Reichelt, who authorized a special payment of 5,000 euros and “told her that she should never tell anyone.”

Axel Springer’s compliance department also received a complaint this year that Mr. Reichelt had provided a forged certificate showing that he was divorced to a woman who was working on contract with Axel Springer and with whom he was having a relationship. A copy of the phony divorce certificate was shared with me.

I did not have access to the complete report by the lawyers who investigated Axel Springer, and the company declined to provide it. Mr. Döpfner said in the emailed statement: “The culture at Bild was not up to our standards and does not reflect the broader culture at the company. To say that it does paints a false view of Axel Springer.”

He also said the Bild workplace culture would not be replicated in the United States. “We will not tolerate any behavior in our organizations worldwide that does not follow our very clear compliance policies. We aspire to be the best digital media company in the democratic world with the highest ethical standards and an inclusive, open culture,” he said.

Axel Springer forwarded a letter from lawyers stating that Bild was not legally obliged to fire Mr. Reichelt.

But a March 1 message from Mr. Döpfner to a friend with whom he later had a falling out over the way the company handled the allegations against Mr. Reichelt, Benjamin von Stuckrad-Barre, suggests that, while Mr. Döpfner was central to deciding how to act on the investigation’s findings as chief executive, he may not have been impartial. In the message, sent after Axel Springer had become aware of the allegations, but before the investigation was underway, Mr. Döpfner referred to an opinion column by Mr. Reichelt complaining about Covid restrictions.

Mr. Döpfner wrote that “we have to be especially careful” in the investigation, because Mr. Reichelt “is really the last and only journalist in Germany who is still courageously rebelling against the new GDR authoritarian state,” according to a copy of the message that I obtained. (The reference to GDR, or Communist East Germany, in this context, is a bit like “woke mob.”) Mr. Döpfner also wrote that Mr. Reichelt had “powerful enemies.”

Mr. Döpfner’s political statement in that message may seem at odds with his stated plans for his new American properties, which The Wall Street Journal reported last week, will “embody his vision of unbiased, nonpartisan reporting, versus activist journalism, which, he said, is enhancing societal polarization in the U.S. and elsewhere.”

As Axel Springer was struggling to contain the fallout from the Bild investigation, Mr. Döpfner’s focus was on Washington. This spring and summer, he conducted secret, parallel conversations with executives at two rival news organizations based in Washington, Politico and Axios, the site started in 2016 by Jim VandeHei, Mike Allen and Roy Schwartz, all formerly of Politico.

Mr. Döpfner’s goal was to buy both and combine them into a mighty competitor to the nation’s largest news outlets. The Politico acquisition, announced in August, was a triumph for his company. But behind the scenes, Axel Springer’s courting style had alienated its other target.

On July 29, Mr. VandeHei, the Axios chief executive, told his board of an unusual situation, according to two people at the meeting. Mr. Döpfner, he said, had floated the idea of installing Mr. VandeHei as the chief executive of the Politico-Axios combination. But Mr. Döpfner knew that Politico’s leadership team, still bitter over Mr. VandeHei’s departure to start a rival publication, would object. So Mr. Döpfner proposed that they keep the deal secret and announce it only after it was too late for Politico to withdraw, Mr. VandeHei told his board.

Mr. VandeHei told the board that he found Axel Springer’s approach “sneaky,” the two people said, and that it was “not how we do business here.” He pulled out of the deal, the people said.

My colleague Edmund Lee, who recently left the media beat for a management job at The Times, graciously shared his reporting with me on the Axios negotiations.

Mr. Döpfner, through a spokeswoman, flatly denied that account. “We were truthful and straightforward about our plans and intentions,” he said. “No lies and no deceptions.”

Read more:

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/17/business/media/axel-springer-bild-julian-reichelt.html

READ FROM TOP....

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW √√√√√√√√√√√√√√√√√√√√√√√¡¡¡¡¡!!!!