Search

Recent comments

- crummy....

2 hours 52 min ago - RC into A....

4 hours 44 min ago - destabilising....

5 hours 48 min ago - lowe blow....

6 hours 20 min ago - names....

6 hours 57 min ago - sad sy....

7 hours 22 min ago - terrible pollies....

7 hours 32 min ago - illegal....

8 hours 44 min ago - sinister....

11 hours 6 min ago - war council.....

20 hours 52 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

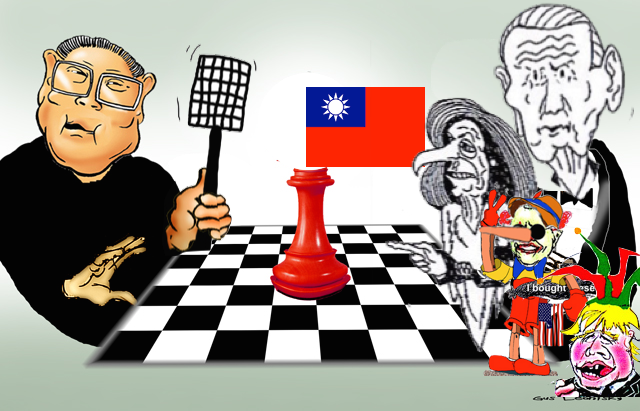

chinese chess...

chinese chess...

chinese chess...

The United States urged China to stop its "provocative" military activities near Taiwan, after the island scrambled jets to warn away close to 100 Chinese military aircraft entering its air defence zone over a three-day period.

Key points:- The US says it is "very concerned" about China's sorties into Taiwanese airspace

- Taiwan's Foreign Ministry thanked the United States for its concern

- China sent 39 fighter jets into Taiwan's air zone on Saturday, the highest number ever reported

Taiwan, a democratically governed island that is claimed by China, has complained for more than a year of repeated missions near it by China's air force, often in the south-western part of its air defence zone close to the Taiwan-controlled Pratas Islands.

On Friday, Saturday and again on Sunday, Taiwan's defence ministry reported that China's air force had sent aircraft into the zone, with 39 on Saturday alone, the highest reported number to date.

"The United States is very concerned by the People's Republic of China's provocative military activity near Taiwan, which is destabilising, risks miscalculations, and undermines regional peace and stability," State Department spokesperson Ned Price said in a statement.

"We urge Beijing to cease its military, diplomatic, and economic pressure and coercion against Taiwan."

The US has an abiding interest in peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait, and will continue to assist Taiwan in maintaining a "sufficient self-defence capability," Mr Price added.

"The US commitment to Taiwan is rock solid and contributes to the maintenance of peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait and within the region."

Taiwan's Foreign Ministry thanked the United States for its concern, and said China was increasing tension in the Indo-Pacific region.

"In the face of China's challenges, our country's government has always committed itself to improving our self-defence capabilities and resolutely safeguarding Taiwan's democracy, freedom, peace and prosperity," it said.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW !!!!!!!!!!!!!!

- By Gus Leonisky at 4 Oct 2021 - 11:40am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

self-censorship...

By Justin O'Connor

It wasn’t foreign interference and influence legislation that got in the way of a recent university event, but the universities themselves, fearful of standing up for academic freedom.

Running a symposium on improving mutual understanding between China and Australia, asking what can we learn from each other proved harder than expected. It ran afoul less of the federal foreign interference and influence legislation than a university fearful of standing up for academic freedom.

In his excellent book China Panic, David Brophy devotes a chapter to the impact of the new cold war with China on Australian universities.

The foreign interference taskforce set up in August 2019 brought peak university bodies into direct collaboration with Home Affairs, ASIO and others. The 2020 Foreign Relations Bill (which has since been enacted) gave the government power of veto on all international collaborations, including those agreed between universities. It is now a legal requirement to register any such agreements, the key test being whether the collaborating university was an “autonomous institution” or not.

Everyone knows this is aimed at China. I have an agreement with the Catholic University of Milan, which was waved through, though I doubt there was any investigation of its close relations with the Vatican.

Brophy concludes: “For all the talk of academic freedom and free speech, today’s policy responses to ‘foreign interference’ effectively increase outside intervention into the operations of universities.”

Over two afternoons last week, two colleagues (University of Adelaide) and I (University of South Australia) organised a symposium, “Different Histories, Shared Futures”, which tried to create a space for dialogue between Australia and China.

It was not uniquely focused on international relations, though of course this was a recurrent theme, but rather on the capacities of each country or “system” to face the challenges of the future. Could we learn anything from each other?

Having arranged the speakers and timetable, we then got onto setting up the online infrastructure, with the University of Adelaide, where the hybrid live/ webcast event was to be hosted. It was at that point, the same day as the AUKUS deal was announced, that the trouble started.

“How am I to fill in this box?” my colleague asked me, sending me the compliance form required by the government. I replied there was no need, as we were not working with any foreign entity. This brief exchange alerted me to a range of other things going on.

I replied both to the school head and the chief security officer (a professor) that this event was not covered by the Act and asked why they were being made to fill out the form. I was told this was simply “due process”, when in fact a simple yes or no question could have shown it was not required.

We were then asked, “Why have you not named Palgrave Macmillan (Singapore or UK) as a foreign organisation involved with the engagement?” This referred to a sponsorship deal with the publisher which, in the end, did not come off. So, it now seems that any conference sponsored by a non-Australian publisher is required to fill in the foreign interference form.

I do not know if such sponsorship by a publisher (and in the social sciences, Palgrave Macmillan is one of the big three or four) is covered by the Act. Perhaps, as with Kevin Rudd or Tony Abbott’s need to register their own “foreign interests”, it is an unfortunate by-product of the kind of poorly drafted legislation which has become a hallmark of this government. However, other demands were clearly not legally required.

My colleagues were asked to submit abstracts of the papers in advance. Then the university’s legal department demanded we insert a disclaimer before each speaker to the effect that these were the opinions of the individual speakers not the views of the universities, not could these universities guarantee the “accuracy or reliability of the information presented”.

In my long career in academia, I have never seen such as disclaimer inserted into a conference brochure — and I’ve spoken in Russia and China.

I asked, twice, if this disclaimer would henceforth be demanded of all external speakers, whatever the topic. No answer was given, for of course the answer would be no. There is no legal need for such a disclaimer, as academics are guaranteed freedom to speak within their field of expertise and general propriety. As a co-convenor from the University of South Australia they insisted that I too must sign up to that disclaimer. I refused and stood down as co-convenor.

The security officer said that “foreign interference” also meant on campus, suggesting that we were naïve to think this would not take place, and that “nefarious actors” might seek to interject.

They demanded we have security, and that I pay half. There was no evidence of any security threat.

Brophy’s chapter again takes us through many examples of on-campus discussions which went off peacefully. These were about Hong Kong and Xinjiang, involving heated but respectful debates between “mainland” and other Chinese students.

Our event was a series of papers in the usual academic style — big words, hand waiving, going over time, etc — not an open public meeting. In the end I was informed, via a senior manager at my own university, that the University of Adelaide had unilaterally moved it all online.

Free speech on campus, in areas deemed sensitive by university managers, is under serious threat.

My Chinese colleagues felt the pressure in ways that I, as an Anglo-Australian, did not. The Chinese community in general is running scared, keeping a low profile, fearing accusations of being fifth columnists.

Only Chinese people with anti-PRC views are now acceptable in the media. As Guy Rundle has written in Crikey over the past week, with the exception of this outlet, the mainstream media has been in lockstep with the government and the military-intelligence community on this. The “left” feels it best to keep quiet. And academia?

After the sentence on academic freedom Brophy writes: “A single-minded vigilance towards China is going hand in hand with the increasing integration of universities with Western military institutions.”

The talk in the Campus Morning Mail after the AUKUS deal, was how the South Australian universities would fair. Flinders — upbeat; UniSA — taken aback; Adelaide— no comment.

Why universities were up to their neck in defence contracts in the first place was never asked. I’ve no idea what defence contracts are at stake amongst the three universities. What is clear at the University of Adelaide is that government interference in academic freedom is not confined to the letter of the law, but also the spirit — management seeking to zealously exceed that legal letter to show their willing compliance.

“Reputational damage” was a phrase used in this exchange. This, we can be certain, does not refer to the reputational damage of undermining academic freedom, but of annoying the government of the day and, potentially, upsetting its brand image.

A report by the Royal United Services Institute in the UK — hardly a hot-bed of Panda-huggers — suggested that the Australian governments rolling together of national security with concerns for academic freedom (citing various pressures placed on overseas Chinese students) was a mistake: “Safeguarding academic freedom depends on a recognition of the important differences between national security and academic freedom issues.” This is something this government does not recognise, and nor, it seems do universities. They are happy to curtail the latter in the hope that they won’t get accused by the government of undermining the former.

David Brophy again:

“It’s imperative that Australian universities resist such pressures. At a time when the national debate surrounding China is so crucial, they cannot afford to simply fall into line with a foreign policy shift that positions China as Australia’s enemy. But in the hands of the small cohort of administrators who currently run them, there is every chance that they will. Having put up precious little resistance to the trend towards privatisation, with all its deleterious effects on the independence of our universities, officials cannot be relied on to resist the political pressures now pulling them in a different direction.”

The University of Adelaide, like all universities, has a duty to protect academic freedom as absolutely central to its public mission. It is abundantly clear that we cannot rely on the university management to protect that academic freedom.

We must turn to the university itself — not the managers who claim that they are the university — but to the staff, students and alumni who are its true body. Which, at a time of savage and mostly self-inflicted job cuts (as Adam Lucas showed in these pages), is going to be a tough call.

Read more: https://johnmenadue.com/cold-war-campus-fearful-universities-abandon-academic-freedom/

abiding by the agreement...

US President Joe Biden says he has spoken to Chinese President Xi Jinping about Taiwan, with them agreeing to abide by the "Taiwan agreement", as tensions ratchet up between Taipei and Beijing.

Key points:"I've spoken with Xi about Taiwan. We agree … we'll abide by the Taiwan agreement," Mr Biden said.

"We made it clear that I don't think he should be doing anything other than abiding by the agreement."

Mr Biden appeared to be referring to Washington's long-standing "one-China policy" under which it officially recognises Beijing rather than Taipei, and the Taiwan Relations Act, which makes clear that the US decision to establish diplomatic ties with Beijing instead of Taiwan rests upon the expectation that the future of Taiwan will be determined by peaceful means.

The comments to reporters at the White House — made after Mr Biden's return from a trip to Michigan touting a spending package — come amid escalations in the Taiwan-China relationship.

Read more:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-10-06/biden-xi-jinping-agree-to-abide-by-taiwan-agreement/100518846

bizarre messaging...

‘The country that bombed you is your friend. The one that built your new railway is your enemy’

This is the Western media’s bizarre messaging to the people of Laos, a nation that was carpet bombed by America, and which is now being vilified for accepting a new $9 billion railway line paid for by China.

Thursday was National Day in Laos, a celebration marking 46 years since the landlocked Southeast Asian nation deposed its monarchy and became a revolutionary communist state, an effort which was supported by Vietnam.

BY Tom Fowdy

This year, the anniversary had added significance, as it saw the opening of a major new project, an electrified high-speed and freight railway system connecting the capital city, Vientiane with its northern neighbour, China.

The $9 billion project is part of the Belt and Road Initiative, and has been hailed as one of its flagship achievements. It is the first commercial and industrial railway in Laos, which, given its geography and the fact it is surrounded by mountainous terrain, has not previously had many options to expand its exports and generate economic growth.

Now, though, it has a direct rapid link into the world’s second largest economy and the world’s largest consumer market by population, and a connection to the booming ports of Guangdong. In terms of what it will bring to Laos, it is a game changer. So, what’s not to like about it?

To nobody’s surprise, the mainstream media have responded to the railway with the usual anti-China negativity. A plethora of articles sought to paint the project as a ‘debt trap’, promoting the accusation that Beijing loans countries money for projects they cannot afford and then exerts political leverage over it.

The Financial Times, for one, ran with a cynical article headlined ‘Laos to open Chinese-built railway amid fears of Beijing’s influence’. It implied that somehow Laos feels threatened or fears the construction of this very pioneering railway project (which the country’s own leader made sure he was the first to travel on). This suggestion of ‘fears of Chinese influence’ has become a common feature on such stories, which seek to cast doubt over anything positive China may be achieving or doing.

A common Twitter meme among pro-China users which has followed from stories like this asks: “but at what cost?” highlighting the frequency of such negative coverage.

And if you Google “China, but at what cost?” you can find a great many examples of articles published in major outlets. In producing such pieces, the broader intention is to depict Beijing’s actions as unwanted, threatening and constantly facing opposition. In the case of the Laos railway project, the ‘problem’ is it was financed by debt, and therefore it is not a positive step.

Yet this argument is as insulting as it is outright insensitive to Laos’ contemporary history. Anyone who knows anything about Laos’ relatively recent past will be well aware that China is not the country to fear, but the United States – the nation that dropped over 260 million cluster bombs on Laos and completely devastated the country as an extension of the Vietnam War, making it the most single bombed nation in history and claiming over 50,000 lives.

Many of these bombs remain unexploded and litter the countryside of Laos, continuing to kill civilians. In constructing the new railway, workers first had to clear the unexploded ordnance. How is it that the world and the mainstream media remain indifferent to this atrocity? And how, by any stretch of the imagination, can they claim that China is the true threat to Laos, and that the US and its allies act in the true interests of the country?

Herein lies the problem. Such a mindset symbolizes the elitism, chauvinism and self-righteousness of the countries of the West, which are ideologically inclined to believe that they stand for the ‘true interests’ of the ordinary people in the countries they profess to liberate.

Western politics peddles the assumption that through countries’ adherence to liberal democracy, they exclusively hold a single, universal, impartial and moralistic truth, derived from the ontological legacy of Christianity, and they have an obligation to introduce it to others. The West always acts truthfully and in good faith, while its enemies do not. And therefore, so the logic goes, any policy the US or its allies direct towards Laos is motivated by sincere intent and goodwill for its interests, and in turn, anything that China does is bad-faith, expansionist and power-hungry behaviour motivated by a desire to influence or control the country.

This creates the bizarre scenario whereby Beijing is depicted as evil and sinister for building a railway to connect to its neighbour – but we should forget America dropping millions of bombs on the country because it was done in the name of ‘freedom’. I’m sure you can imagine how the media would react if China did the latter.

Read more:

https://www.rt.com/op-ed/542114-railway-china-laos-us/

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!