Search

Recent comments

- crummy....

2 hours 52 min ago - RC into A....

4 hours 45 min ago - destabilising....

5 hours 48 min ago - lowe blow....

6 hours 20 min ago - names....

6 hours 57 min ago - sad sy....

7 hours 23 min ago - terrible pollies....

7 hours 32 min ago - illegal....

8 hours 44 min ago - sinister....

11 hours 6 min ago - war council.....

20 hours 52 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

beyond the atlantic...

grant

grant

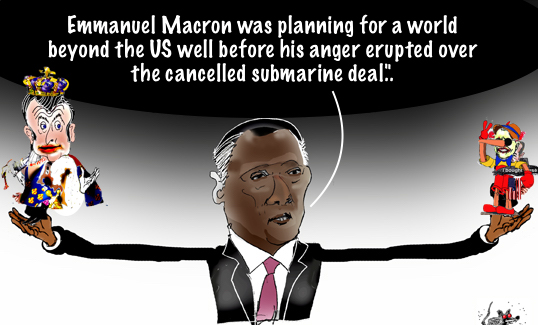

Emmanuel Macron was planning for a world beyond the US well before his anger erupted over the cancelled submarine deal.

The French President calls it strategic autonomy; it could just as easily be named "Europe first". Macron says Europeans must stop being naive and develop the power to defend themselves.

And that may now extend to rethinking NATO, an alliance Macron has previously described as "brain dead".

By Stan Grant

Would France leave NATO? Well, it has before — sort of. In 1966, President de Gaulle withdrew his country from NATO's command structure, albeit remaining an active member of the alliance. It didn't "rejoin" NATO until 2009.

The submarine spat has some wondering if Macron may do a de Gaulle. It's unlikely, but that it is speculated at all reminds us that there is a significant geopolitical shift underway.

Macron is adjusting to life in what's been called a "post-American world".

As Donald Trump, during his presidency, questioned the value of NATO and accused European nations of not paying their way, Macron warned that Europe could not depend on American military support.

Now you can add betrayal to that. Macron feels cheated, accusing America and Australia of lies, duplicity and treating France with contempt.

These are not just the angry words of a jilted partner. This runs much deeper. France is not a country easily ignored or lightly scorned. It is a powerful nation: nuclear armed, it has the sixth largest defence budget in the world and the largest in Europe. By some measures it has the largest army in Europe.

France is one of five permanent members of the UN Security Council. And it is an economic power — the seventh biggest economy in the world.

France's shadow

It is fair to say France casts a bigger shadow than Australia. France projects its power and influence beyond Europe, into the Middle East, Africa and the Indo-Pacific.

France is a serious Pacific power. It has 8,000 troops in the region, more than any other country apart from the US. It has up to two million citizens here and controls territory.

If we want a more stable region, France must be at the table. Rather than alienate France, Australia should be getting closer to it. Former Defence Department Director and Federal Vice-President of the Navy League, Mark Schweikert, says we need to give "greater thought and attention" to our relationship with France.

Writing in the journal The Navy, he says French territories could be "key anchor points for influencing/controlling the South West Pacific".

All of this, of course, is designed to blunt rising Chinese power in the region. But does France — indeed the EU — see China as the biggest threat?

France says it is a "stabilising power". The Centre for Strategic and International Studies says France wants to strike "an equilibrium between the indispensable balancing against China with the need to avoid an escalatory posture towards Beijing".

Simply: be wary, be prepared but don't be provocative.

France led Europe in devising an Indo-Pacific strategy. Until recently, the EU had no plan for the region. Remarkable when you consider how our neighbourhood will determine peace and prosperity for the 21st century. Now, the 27 EU foreign ministers have signed on to a security blueprint.

The EU is cautious. There is no talk, though, of confronting or containing China. Where the US names China as a "strategic rival", European nations prefer the word "inclusivity". They want to incorporate China — it is all about cooperation.

Europeans don't see China as an enemy

The EU has a lot at stake; China has surpassed the US as the European bloc's biggest trade partner.

The European states themselves are split on what the Indo-Pacific strategy means. Writing for the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), senior policy fellow Frederic Grare and Asia Programme coordinator Manisha Reuter point out:

"Western European states tend to view the prospect of an EU Indo-Pacific strategy as both a way to manage the transatlantic alliance and an assertion of strategic autonomy; eastern European states regard it as a way to manage the transatlantic alliance and align with the US."

Europeans generally don't see China as an enemy. An ECFR poll of European states shows a majority believe that a new Cold War is underway, but they don't think they are part of it. According to the survey, Europeans don't see the world as a great battle between authoritarianism and democracy.

Very few of those polled see China as a threat to their way of life and most see Russia as a greater challenge. And while Australia is doubling down on the American alliance, Europeans question the need for America as the big defender.

This likely reflects geography. Europe is far from what some see as the emerging Indo-Pacific battleground. Europeans may well be complacent; they'd do well to wake up to China's assertiveness and bullying.

Read more:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-10-03/macron-submarine-australia-france-china-power-shift/100506622

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW !!!!!!!!!!!!

- By Gus Leonisky at 4 Oct 2021 - 5:37am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

submarine fairyland...

BY Mike Scrafton

The relationship between defence policy and the nuclear powered submarines has generated a lot of magical thinking.

Defence planning takes place at the intersection of threats, geography, time, and military capability. It deals pragmatically with reality. That is, which threats are credible, when will they emerge, and the relative strength of the forces during the planning period.

The consensus seems to be that over the coming decades the most demanding potential missions for the ADF are to join a US coalition against China in East Asia, or to defend Australian sovereign territory, maritime or terrestrial, against Chinese aggression.

In an informative paper, Marcus Hellyer has produced a table based on current information showing that a nuclear submarine capability might not be fielded until well into the late-2050s. If so, nuclear submarines will play no role in Australia’s defence planning for a minimum of at least thirty-five to forty years.

The putative strategic benefits the nuclear submarines might provide before then are imaginary. By the late-2050s the strategic environment in East Asia will undoubtedly have shifted radically; whether in China’s or in the US’s favour is unknowable. So Australia’s eight submarines, maybe three deployable, are probably going to be of marginal relevance beyond 2050.

Even if by some miracle Australia was able to deploy two or three nuclear powered submarines on operations much earlier, say the mid-2040s, that still won’t meet Michael Keating’s criteria that “[T]he reason we need nuclear submarines is precisely because we must be able to defend Australia on our own”. Or that the nuclear powered submarine “would make any country think again about attacking us”, as he and Jon Stanford assert.

For the next three decades at least Australia simply won’t have a nuclear submarine capability. These interrelated ideas—that Australia could actually independently defend itself because of the addition of the nuclear submarines and that therefore China would be deterred—both suffer from the same faulty strategic thinking.

Of course China would think seriously about whether or not to use military force against Australia. Moreover, like any nation, if China’s motive was sufficiently important it still would act. That’s the strategically important point.

Keating’s notion that a nation can “deter possible aggression by [its] ability to impose heavy costs on the attacker” ignores the costs on the defender.

The costs of conflict are always relative and the very powerful states can absorb costs, when considered necessary, that are beyond smaller states. If, in the real world, China has sufficient reason to attack Australia to defend its interests, the asymmetry in the forces means that it would do so, even if the imaginary submarines magically materialised.

In addition, in military operations costs can be avoided or minimised by planning and superior tactical effectiveness, as well as by overwhelming force. Over the next several decades, China would have many other options than exposing its forces to the limited number of nuclear submarines Australia could deploy, if Australia had them. Even if China were concerned, thirty years would give its planners plenty of time to plan and act well before Australia had a credible nuclear submarine capability.

But some costs are unavoidable in war and what is an acceptable cost is just a factor in the strategic calculation. The sheer asymmetry between the Chinese and Australian forces means, that in the absence of the US, China could accept costs that would prove catastrophic for Australia. That’s the definition of winning.

It is foolish to believe that China would launch an assault against Australian territory or assets just because they could and without a national interest being at stake. Although the prospect that they might undertake military action in a bilateral crisis is increased by their capacity to do so. It would be magical indeed to believe the Chinese would discount their chances of success because of nuclear submarines that don’t exist.

The magical thinking of the nuclear submarine advocates imbues the vessels with the mystical power that the French placed in the Maginot Line, even though they are only imaginary. Unlike the Maginot Line, because the submarines don’t exist, and won’t for decades, if ever, a potential aggressor doesn’t have the incentive to come up with tactical solutions in the same way as the Germans when confronted by French fortifications in 1940.

An East Asian war is less likely if the US withdraws, but then Australia could not be defended against a determined, committed, and unconstrained China, submarines or no submarines. Even Michael Keating thinks that “looking ahead another 20 years, it is doubtful whether the Americans will still be maintaining a presence off the coast of China”.

Doing the sums, Australia is likely to be facing China alone from 2040. On Hellyer’s analysis that is still twenty years away from a credible nuclear submarine capability. Unless the Americans are also indulging in magical thinking, they cannot be relying on the Australian submarines to contribute to a war for a long time. Logically, it is only the prospect access to Australian bases that is important to the US.

The incontrovertible fact is that submarines that don’t exist cannot either defend or deter. It is magical thinking to believe imaginary capabilities can be part of a real defence policy.

Read more:

https://johnmenadue.com/magical-thinking-nuclear-submarines-and-australias-maginot-line-of-the-imagination/

See also:

Naval technology is developing so rapidly that Australia’s new $50 billion fleet of submarines may one day have to face deadly underwater drones, an expert has warned.

Earlier this month, the federal government announced the signing of the Attack class submarine Strategic Partnering Agreement with French shipbuilder Naval Group.

It will build 12 attack submarines to replace the Royal Australian Navy’s ageing Collins class vessels, with the first one scheduled to be delivered in the early 2030s, the federal government said.

But Russia has already provided a glimpse of underwater autonomous – or drone - weaponry.

The Russian Ministry of Defence released testing footage of its ‘Poseidon’ – a high-speed nuclear torpedo.

Naval chiefs said the weapon is capable of carrying both conventional and nuclear warheads and will have a maximum speed of 200 km/h. It is designed to attack enemy aircraft carriers and shore installations.

The footage is the first to show the weapon operational, even if only in what appears to be a testing pool.

Russian defence officials said its navy plans to launch its first nuclear powered submarine capable of carrying the Poseidon over the northern spring.

Defence analyst Marcus Hellyer told nine.com.au the new Australian submarines will face the challenge of adapting to rapidly developing technologies.

"Drone submarines look like being the future of underwater warfare. Initially they may be launched from a type of ‘mother ship’ before carrying out reconnaissance missions.”

Dr Hellyer, a senior analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, said in the future advanced underwater drone weapons may make the ocean “too dangerous” for submarines with human crews.

But he said Australia’s close links with the US Navy as well as other western countries such as the UK and France would help it adapt to emerging technologies.

“There has been close co-operation with the US Navy for many years.

Read more:

https://www.9news.com.au/national/news-world-drones-the-future-of-underwater-warfare/658c941c-5827-43ff-9a96-bbe97260ca7f