Search

Recent comments

- epibatidine....

3 hours 7 min ago - cryptohubs...

4 hours 6 min ago - jackboots....

4 hours 14 min ago - horrid....

4 hours 22 min ago - nothing....

6 hours 45 min ago - daily tally....

8 hours 7 min ago - new tariffs....

9 hours 58 min ago - crummy....

1 day 4 hours ago - RC into A....

1 day 6 hours ago - destabilising....

1 day 7 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

arming university aussie bozos...

uni-

uni-

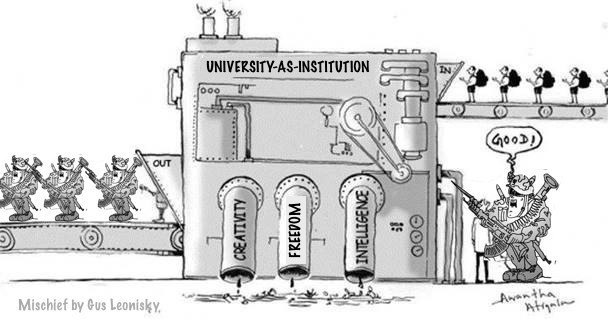

It is now unambiguously clear that certain influential centres of government advice and government policy hold the university-as-institution in contempt.

More specifically, they hold the ideal of the traditional university in contempt, and by the ideal, I refer to a reasonable concept which, with good will and adequate funding, is also achievable in most, if not all respects. Regardless of its faults, it was an aspirational site and survives a popular belief in some quarters of modern democratic societies that the universities are unique as sites of teaching, inquiry, research, and writing which, above all, are marked by their independence from the various forces which influence so much of the life outside of the academy.

The academy, in these terms, approximates to an ideal which, though it never existed, continues to be honoured in the terms put forward by Wilhelm von Humboldt, as:

“. . . nothing other than the spiritual life of those human beings who are moved by external leisure or internal pressures toward learning and research. “

But this is more than an ideal proclaiming the need for the satisfaction of a personal yearning; indeed, its wider, extremely serious ramifications are apparent in the comment it attracted from Noam Chomsky:

“The extent to which existing institutional forms permit these human needs to be satisfied provides one measure of the level of civilisation a society has achieved.”

Historically, moreover, to the extent that the University approached von Humboldt’s ideal in more than a vestigial resemblance it “reduced the entropy of time and fought against it;” fought against it, furthermore, as a stable institution, able, because of its historical consciousness, “to preserve at least a pocket of memory, “ and maintain, as Regis Debray recalls it, “a tribal reservation for the ethics of truth.”

Within it, which is to say within the membership of the academy, education and abnegation were “virtually synonymous,” a deceased identity which Debray laments with just a hint of contempt for its successors:

Integrity, obscurity, selflessness; the words raise a smile, but the archaism of the vocabulary derives from the downgrading of the practices of the schools, not vice versa.

The University, then, was of course a dominant site of secular critique practised by people “capable of living what [they] taught until it killed [them]. In their commitment to this principle, to what Paul Bové sees as the imperative to “take aim at the unequal, imperial, antidemocratic present,” academics demonstrated a truth: “Critics should never be good company.”

And both Debray and Bové, just to name two, are intent on making even more explicit as the purpose of University education – the need to provide the bases of that “educated and active citizenry [which] is indispensable for a free and inclusive democratic society” within the belief that critical citizens are made, not born.

In turn, this democratic education must take the form of being “an education for democracy . . . it must argue for its means as well as its ends.” Ultimately, this is to be encapsulated within the principles which all education should take place – the foremost being “intellectual freedom and ethical responsibility.”

It is against this concept as measure that a recent offering by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute is set. It provides, succinctly and clearly, another example of the now reigning view of the University from those trusted with providing policy advice, which is to say, it is corporate, predatory and and ignorant. And it does this under the camouflage of appearing to offer the University a way out from some of its troubles by appealing to the contributions it can make to national security. That said, it is, prima facie, a slick operation.

Given ASPI’s standing in matters of national security advice, its views might even be implemented, That is the reason for this two- part rejection: they would lead to the further impoverishment and balkanisation of higher education in Australia.

In a relatively short recent paper of 12 substantive pages, published by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute entitled An Australian DARPA to turbocharge universities’ national security research: securely managed Defence-funded research partnerships in Five-Eyes universities, authors Robert Clark, a former chief defence scientist, and ASPI’s executive director, Peter Jennings, identify what they see aa significant opportunity to boost international defence scientific and technical research cooperation with ‘Five Eyes’ partners the United States, Britain, Canada and New Zealand.

In what has become standard practice, and presumably in anticipation that those with extremely limited concentration spans would be challenged by the time to read and reflect upon the pronouncements from the apex of ASPI, an almost immediate epistle – essentially an abridged, judiciously selective, Pauline attempt to explain the important points of the reigning theology found in the original – was issued.

DARPA, here, refers to the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the template upon which an Australian version would be based. It is described as “an innovation ecosystem that includes academic, corporate and government partners spanning from open-domain to classified research.”

At its core the ASPI’s proposal focuses on science and technology; Australia should establish its own DARPA by way of a formal partnership between the Defence Department, defence industry and Australian universities. Accordingly, the US model is heralded as providing “best practice guidance” for such an undertaking.

The source for, or register for this claim is not cited. This might be just as well because the open-source history of the US universities’ involvement with the national security state should not encourage Australia to emulate it.

The springboard for this is to be provided by Australia’s – Next Generation Technologies Fund (NGTF) – with its nine priority areas: integrated intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance; space; enhanced human performance; medical countermeasures; multidisciplinary material sciences; quantum technologies; trusted autonomous systems; cyber and advanced sensors; and hypersonics and directed energy.

Central to the envisaged partnership to produce more efficient killing machines the proposal advocates ‘the need to restructure current arrangements for Defence funding of Australian universities’ in order that Australia maintains ‘a strong and sovereign university research base with the capacity to support industry, the community and national security.’

Other rationales include:

- A release from both the policy of underfunding of national universities by Australian governments and concomitant financial and security risks of Australian universities over-dependence on funding sources from the People’s Republic of China in particular and international students fees in general.

- The need to follow the US in which universities as an important part of the national security enterprise and, are thus, subjected to stronger regulation and oversight (and will necessarily include high-level security clearances for this involved) – an approach which will increasingly inform thinking among democratic governments around the world. Failure to follow suit will almost certainly result in diminished research relationships with the US.

- The current, largely open approach of Australian research universities to their international links is, rather than a matter of intellectual pride, a significant weakness.

- This initiative is necessary because the mission-oriented research carried out by Australian government agencies—Defence Science and Technology Group (DSTG), CSIRO, Geoscience Australia, the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation and others are incapable of doing the work which needs to be done.

Immediately apparent is the distance the University has traversed from the reasonable ideals which, disingenuously, and usually at graduation ceremonies, those entrusted with the stewardship of universities still proclaim.

To be clear, shorn of the embedded Sinophobia which infuses so many of ASPI’s political-strategic analyses, the funding problems which a neoliberal approach to higher education are accurately described and no issue is taken with them. Indeed, they would support the conclusion that the universities now constitute an educational dystopia – and deserving of Richard Hil’s recent dismissal of them on this site as “no longer fit for purpose.”

Against this diagnosis, however, is ASAPI’s prescription, a programme which cannot be seen independently of its corporate mentality; indeed, it is a demonstration of it.

The universities are viewed as suitable recipients of alms and/or places to be pillaged. The fundamental questions as to how and why this is the case are ignored. Dependency on the revenue stream generated by international students is not the root cause; for that there is a need to confront the neoliberal fundamentalism practised by successive governments, a measure seemingly beyond the courage or the imagination, of the ASPI proposal. Similarly, the dismissal of the capabilities of the government research agencies is neither explained nor are policy and budgetary remedies suggested.

Instead, the focus is on what is essentially a hostile, corporate takeover of parts of the University which are deemed useful to national security. It is a process of securitisation and militarisation by stealth, and its consequences – outlined in Part 2 – will be ruinous, both for those in the academy who enlist in the DARPA-isation, and those who walk in the shadow of the now humiliated concepts of the roles and functions of the University.

Michael McKinley is a member of the Emeritus Faculty, the Australian National University; he taught Strategy, Diplomacy and International Conflict at the University of Western Australia and the ANU.

Read more:

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....

- By Gus Leonisky at 12 Aug 2021 - 7:45am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

contempt for universities...

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s recent proposal to enrol the science, technology, engineering and mathematics areas of the research universities as part of a national security establishment along the lines overseen by the US Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency is a regrettable initiative.

First because of the contempt it displays for the University as a place of learning. Secondly for the inevitable and considerable danger for the university system should the proposal be implemented.

https://johnmenadue.com/aspis-proposal-to-further-militarise-and-securitise-the-university-contempt-for-the-tradition-of-research-and-learning/

For those who have paid attention to the evolution of the Australian universities under neoliberalism (and before for that matter), ASPI’s proposal is but another offensive against the traditional and reasonable concept of the university – a concept frequently declared on feast days of the university to placate those who, worried about the evidence, envisage it as more than a tool shop for the established political, social, and economic order

Operationally, however, the universities revert to the standard operating procedures demanded by that order. Their status is pathetic: secular monasteries inhabited by various types of mendicant orders in the land of infidels, apostates and barbarians in relation to the best traditions of the Enlightenment.

For the most part – Ramsay Centres for Western Civilisation being one notable exception – they are generally indiscriminate as to who they accept funds from on the grounds that they cannot afford to be sensitive to their provenance. They are, therefore, suitable places to be plundered, hamlets to be colonised by the security agencies of the state.

For all of that, to anyone who has been paying attention to press releases and announcements from the main research universities, the ASPI proposal is but a call for the intensification of existing practices: Defence already funds university research and teaching in several areas and not just in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) which are the focus of the ASPI’s Australian DARPA proposal.

By way of two examples, it might be recalled that early work on certain Star Wars (rail gun) technology was conducted at the ANU, and opportunities to participate in the Minerva Project, an initiative with a strong preference for anthropologists, but generally “designed to mobilise social scientists for open research related to the war on terror” . . by “researching the relationship between Islam, violence, and terror, and proposing new experimental fields which . . . might be as useful . . as game theory proved to be during the Cold War”(sic). On close examination, it was found to be subversive of sound research funding, and sound intellectual practice.

When parsed for not only greater detail, but also for what it leaves out, an implemented proposal would have Australian universities follow their US counterparts down a track which leads to serving the objectives of the Military-Industrial-Complex MIC) through satisfying their technophilia by providing the bases for for more efficient instruments of death, destruction, and population control.

This will, of course, be justified in the name of deterrence. The problem here is that this over-used benediction has been seen to be intellectually and empirically wanting – which probably accounts for the fact that it is studiously avoided by those who most deeply know it.

For the university-as-institution the current dystopia will be exacerbated, in the first instance, to cloaks of secrecy and a faculty divided by access to knowledge and radically different modes of performance evaluation. What is made quite explicit in the ASPI proposal is the need for appropriately security-cleared academics. Equally, it is clear that those so cleared will be assessed by other so cleared against criteria that are determined by satisfying the objectives of the MIC and not peer-review. Mutatis mutandis, this will apply to the postgraduate students who will be involved. It cannot be otherwise given the classified nature of the research in the first place.

Nevertheless, on the basis of attracting significant revenue streams a new national security-relevant clerisy will be ushered in and they will enjoy the status and privies of an exalted caste. Implicit in the ASPI proposal is that, on the completion of their respective projects they will return to their previous academic lives.But how credible is this?

Once joined, life within the clerisy will become habit forming and addictive. The numerous studies and analyses on British, but especially American academics indicate that a “return home” is not to be contemplated with equanimity. For their Australian counterparts the thought of being immersed in lecturing, tutoring, examining, and the overburden of administrative dross would be a carceral sentence.

And some students might justifiably ask whether they want to be taught or supervised by an academics who have spent several years of their lives perfecting or advancing instruments of death, destruction, and political control.

These objections, and others of a similar character, are unlikely to receive serious consideration in the chancellories of the universities. Indeed, there is an ongoing proliferation of things labelled “centre” and “institute” across the campuses of Australia, all representing exceptions, special interests, privileged funding sources.

If anything, and with regard to very recent developments, the resistance might for the present, be futile. Last month ANU, with no sense of irony, let alone shame, announced that former Army Major-General, and Director-General of ASIO, Duncan Lewis, had been appointed a “professor in the practice of national security” in the university’s National Security College (NSC) with a brief to strengthen the links between the NSC and government.

What more is to be said except, perhaps, Kurt Vonnegut’s memorable phrase,” and so it goes” To be sure, the NSC could never be accused of identifying with an open university and academic freedom in the Enlightenment tradition – its advertisements for suitably security-cleared academic staff when it was first established puts paid to any such suggestion. But celebrating the professorial appointment of a person who has spent his entire career discretely eschewing open debate, and withholding or managing information and ideas on national security is an explicit episode in self-harm.

Such people, no matter their previous lives of faithful, distinguished service, belong elsewhere, off campus, in the privileged centres and institutes they should take with them. On some things, and on the basis of the historical record, this is one of them. Augustine, Bishop of Hippo, was right: moderation is impossible; abstinence should be the rule.

Read more: https://johnmenadue.com/aspis-proposal-to-further-militarise-and-securitise-the-university-part-2/

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!